By Thomas Bartlett Whitaker

Muneer Deeb. Anthony Graves. Michael Toney. Robert Springstein. These names probably mean nothing to most of you. Who among us, after all, could possibly even begin to keep track of all of the countless happenings in our modern hyperactive news cycle? We tune in, get blitzkrieged into sensory overload for half an hour or so by events the world over, and then numbly stumble back to the relatively minor disasters of our own lives. For most people, life presents us with more than enough problems to deal with, thank you very much, without wandering about in search of more. Only rarely do catastrophes shock us into collective action, and even when we are roused we do little because our attention spans are short and our political process easy to forestall. What happened in Newtown was a wound on the body of our collective selves, but instead of cleaning it and properly binding it, we allowed it to become infected. We Americans know about these sorts of injuries – we are, after all, masters at both giving and receiving them. We always seem to find the excuses or the distractions necessary to usher in a period of skilled procrastination. Surely, we think, this pain in my belly is just indigestion. Or maybe I pulled a muscle? The party must go on! It’s only after the discomfort becomes an agony that we see the doctor, and, lo, find the tumors. Those names above? You don’t know them, but they were the hot flashes, the warning fevers, the dull aches. They were the initial blood tests that we chose to ignore, afraid of what we might find. And all the while, the cancer grows.

It is no longer really “news” when the press issues details about an exoneration. Twenty-seven years, fifteen years, nine years; we think: how awful, and then go about packing the kids’ lunch. To be honest, when I was still a citizen, I can’t remember ever caring about such things. I had no connection to them, no code of ethics that would have compelled me to forge that connection. I was full of justifications: What can any single man or woman do in the face of government inefficiency and error? You know the ones – you’ve used them yourself often enough. I had no concept of what social movements were about, what my vote actually meant. And I had enough of a mess to deal with on my own plate without looking to add someone else’s portion as well. It took me coming to death row to truly understand what the horror of a wrongful conviction really means in social, cultural, and human terms. And now that this thing is in my head, I can’t seem to get it out again.

It bears mentioning that when an exoneration takes place, the public is really only witnessing the final, labored paces of a marathon which often stretches backwards in time for decades. You see only the glorious denouement, never the tragedy of a gavel slamming one life into another, the tears, the impending madness, the suicidal thoughts, the loss of family and friends. I have to believe that if you saw but a tiny percentage of the full course of the race, if you were forced out of your comfortable cocoons and made to see yourself as the participants that you surely are, this system would crumble under the weight of your ire. I think that if you understood the Herculean effort required to pull an innocent human being out of these pits, it would cause you to see groups like the ACLU, the NAACP’s LDF, and the Innocence Project as the heroes that they truly are. Most of the frequent readers of this site are aware that when a man or woman walks free from prison as a legally innocent and restored citizen, the judicial system was not responsible. There are no roving bands of oversight attorneys working for the state court systems that peruse legal files and occasionally say, “Well, gee, this one here just doesn’t look right.” No, this process always begins with a newly convicted person crying out in the wilderness that the social contract has betrayed him. We see his chains, we see his crime, and then we turn our backs and we walk quickly away. From this point forward, he is mostly going to be toiling against his fate alone. He might have a few friends and family members who stick by his side for a season or two, but even these will fade away over time. Put yourself in this person’s cheap canvas prison-issued shoes for a moment. You have little to no money. You are sharing a cell (sometimes as small as 6X9 feet) with a criminal, working long hours for little to no pay – if you are lucky, that is; you could be simply and arbitrarily placed into solitary confinement for decades. Every facet of your life is controlled, every created and natural desire denied and forbidden. After a few years of fighting against this tide, most people simply give up and are taken by the undertow. It takes a remarkably strong-willed person to keep his head above water, to organize and marshal what few resources he possesses towards finding the sort of help he is going to need to prove to the world that he is not the man they think him to be.

The sorts of organizations that exist to provide this assistance are few and far between, always overworked, perpetually underfunded. They receive so many requests from the innocent and faux-innocent that they can only begin to evaluate a microscopically minute portion of the cases forwarded to them. Usually, cases without clean and convincing exculpatory DNA evidence are routinely ignored. Even when a case does appear to perfectly fit these strenuous requirements, the people doing the investigatory work are law students and professors, working on their own time and funds. And from the very first filing to the final steps outside the courtroom doors, the state is going to fight them tooth and nail for every last inch. It’s amazing that the Innocence Project has freed more than 300 innocent human beings from prison. Change the register a little, and it’s equally amazing that they even managed to free a single one.

There have been many excellent articles written over the years explaining how a wrongful conviction came about (see <HERE> for a superlative example). Such articles are needed as educational tools, but it is important to note that these are always written only after the battle has been won, only after the convict has been formally transformed back into someone for whom society permits itself to empathize with. Articles making declaratory statements of innocence prior to formal exoneration are few and far between, especially ones written by reputable news organizations. This is journalistic cowardice to be sure, a direct result of the capitalization of news outlets, where the truth is only the truth if it sells well. Asking random people to take a chance on innocence, to believe in someone that may have once done something terrible, is not easy. It’s going to offend people. It’s certainly not going to sell ads. And, on a deeper level, the resistance one finds in the embedded media outlets on this matter highlights the single most powerful driver of wrongful convictions, one that no one ever writes about: When an innocent man goes to prison, we are all participants in the process. We contribute by voting in politicians who care more for the stern soundbite than honesty on human rights, and we participate in our silence and absence of anger when we see a man freed from his chains. Very simply, we become complicit when we routinely view this sorry spectacle and neglect to contemplate the social and cultural mechanisms that allowed a wrongful conviction to have happened in the first place. And all the while, the cancer continues to spread.

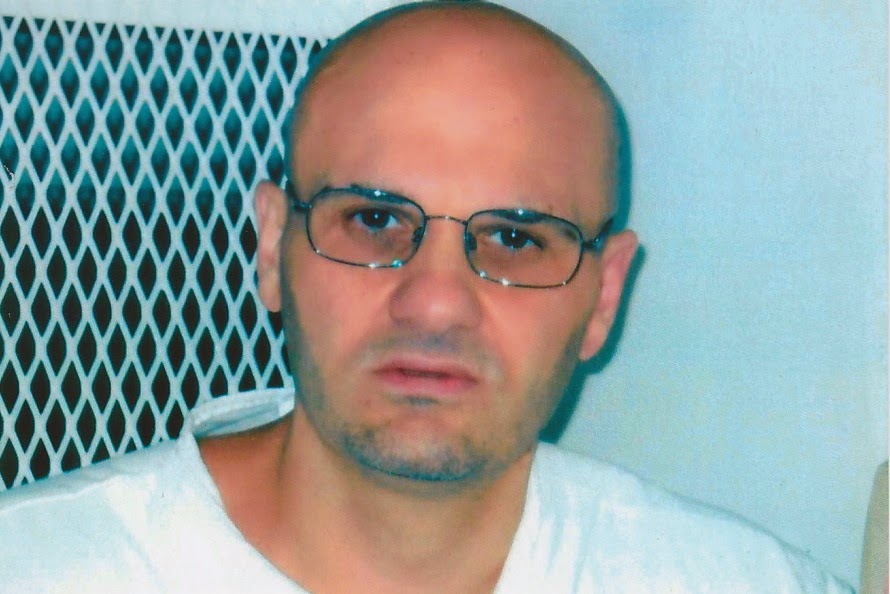

Over the course of the next six days, I am going to walk you through such a case. The facts are horrible, and nearly everything you will find on the internet about Ronald Jeffery Prible, Jr. will lead you to believe that he is human scum. If you have a sensitive stomach, perhaps this series is not for you. I will not be including crime scene photographs, but it is impossible to convey the necessary facts without discussing in detail some very horrible realities, and I tell you in all kindness that this is not going to be a pretty journey. I simply don’t know how else to show you what needs to be seen. I hope, in the end, to have given you the clearest view possible of the broken appellate process which currently operates in Texas, and what this says about the politicians who designed it and allowed it to continually process corpses so that they could get re-elected. By extension, I hope to also point a mirror back at the rest of us who do nothing to stop them. I have managed to procure pretty much everything relevant to the Prible case file, including some items which are only now being made public and some others which are simply too wispy to serve any objective other than engendering speculation. I am including a few examples of the latter because Jeff’s innocence is not proven at this point and the state continues to obfuscate and withhold evidence, making some theoretical connecting of the dots necessary. Even without such leaps of logic, this is, without a doubt, the most blatant example of prosecutorial misconduct that I have ever witnessed. A man was convicted of capital murder and sentenced to death based on fabricated and blatantly perjured “expert” testimony combined with an organized ring of jailhouse informers. All of this testimony has recently been proven to have been concocted with the assistance of the lead prosecutor trying the case. Despite this, the all-Republican Texas Court of Criminal Appeals affirmed the conviction and sentence nine votes to zero, and the odds of Jeff ever escaping the needle are slim. As I said, this is not going to be a pretty journey, but this is who we are. If innocent men are to be carted off to Huntsville to be intentionally overdosed on shadily-procured barbiturates, we should at least have the decency not to blink. I think we owe our fellow citizens at least that much.

Jeff’s case involved the deaths of five people, three of them little girls. At around 6 a.m. on the date of 24 April 1999, a man named Gregory Francisco noticed that smoke was pouring from a neighbor’s home across the street. This house belonged to Esteban “Steve” Herrera and his fiancée, Nilda Tirado. Also living in the home were Tirado’s seven-year-old daughter Rachel, Herrera’s seven-year-old daughter Valerie, and the couple’s 22-month-old daughter Jade. When Francisco approached the smoking residence with his wife, they heard loud music emanating from within. The doorknob was warm to the touch, but Francisco kicked it open anyway and immediately saw Steve’s partially burned body lying in a pool of blood. When he tried to turn him over, the movement pulled chunks of skin off the dead man’s face.

Nilda was found in the living room, “charred from the exterior.” When the autopsies were completed, Steve was found to have died from a penetrating gunshot wound to the back of the neck that severed the spinal cord. The stippling around the wound indicated that the assailant had fired the gun from a distance of less than eighteen inches from the back of his neck. Nilda died from a perforating gunshot wound to her neck that also severed her spinal cord. The children all died from inhaling toxic levels of soot and carbon monoxide. The fire was intentionally set, obviously, and a burned red plastic gasoline container, an aerosol can, and a roll of paper towels soaked in a flammable liquid were found in the living room. A burned one-gallon metal can was also found on the counter near Nilda’s body; this liquid was later determined to be Kutzit, an extremely flammable liquid used by construction workers to dissolve tiling glue.

The basic facts are these: Jeff was the last person to see Steve and Nilda alive. He would admit to having a sexual relationship with Nilda. He is a former Marine, the kind of person capable of hitting a spinal cord on a moving target. He was a criminal – a bank robber, as it would be revealed – and Steve’s partner in crime. He knew that Steve had amassed more than $84,000 in cash for the purpose of buying and then flipping six stolen kilograms of cocaine, and he knew that this money was in the house on the night of the murders. He would be taken in for questioning the following day, and, eventually, years later, would be sentenced to death for the crime.

I want you to pause for a second. Analyze your feelings in this exact moment. Imagine that you had heard the previous paragraph not from this site, but rather from the melodious voice of your favorite local evening news reporter. It’s okay if what you are feeling sounds something like “hang the bastard.” It is right to feel aversion, disgust for crimes like these. It is natural to want justice or those three little girls. But before I write anything else about this crime, I want you to recognize one thing: that anger, that desire for vengeance, justice, a reckoning – that is the single most important variable in the equation of a wrongful conviction. Honest prosecutors can use that emotional complex to drive home what they believe to be true. Crooked prosecutors, on the other hand, can use it to sugar-coat their fabricated “truths” so that they go down easier. In the hands of an able prosecutor, your rage is a cudgel; in the hands of a crooked prosecutor, it is a grenade. In the hands of Kelly Siegler, it’s an atom bomb. Above everything else, recognize this: When an innocent man is sent to death row, the prosecutor played the tune, but it was you who were dancing to the beat.

To read day two click here

Ronald Jeffrey Prible 999433

Polunsky Unit

3872 FM 350 South

Livingston, TX 77351

5 Comments

How Two Men Convicted by Kelly Siegler Uncovered the Dark Secret to Her Success - The Daily Dispatch

January 2, 2024 at 10:01 am[…] to a friendly press, an incarcerated writer at Polunsky named Thomas Whitaker published a sprawling series about Prible’s case on his blog, Minutes Before Six, with the help of supporters on the outside. […]

How Two Men Convicted by Kelly Siegler Uncovered the Dark Secret to Her Success – NewDYRTO

December 21, 2023 at 10:36 pm[…] to a friendly press, an incarcerated writer at Polunsky named Thomas Whitaker published a sprawling series about Prible’s case on his blog, Minutes Before Six, with the help of supporters on the outside. […]

Anatomy of a Wrongful Conviction Day Eight - Minutes Before Six

September 11, 2023 at 12:51 pm[…] about the case of Jeff Prible in 2014; you can read the original six parts of the series <here> if you care to. I wrote an <update> in 2017, and it is to […]

Anatomy of a Wrongful Conviction – Day Two - Minutes Before Six

April 28, 2023 at 6:38 pm[…] read Day One, click here The night before the murders of Steve Herrera, Nilda Tirano and their three children was not […]

Farewell To John Ramirez - Minutes Before Six

February 12, 2023 at 4:13 pm[…] From Jeff Prible: […]