By Thomas Bartlett Whitaker

To read Day One, click here

The night before the murders of Steve Herrera, Nilda Tirano and their three children was not atypical in any appreciable way. Steve’s occupation on the tax records was as a tile setter, an activity he actually did on occasion perform. His primary source of funds, however, came from the sale of cocaine. His marketing techniques were rather primitive, it must be said. Steve was a talented pool shark, often participating in amateur billiards competitions. To set up his narcotics sales center, he simply bought a pool table and installed it in his garage. If the door was open, so was he for business. Whenever a customer would pop in, Steve simply shut the door, handled the transaction, and then promptly went back to playing 9-ball.

One might imagine that such a set-up could prove problematic for the safety of the other four human beings sharing the residence with Steve, but one would be wrong, at least until the night of the murders. Steve was a feared man and simply had few disputes on his home turf. That is not to say that altercations never occurred. Just one month prior to his death, Steve drove to a buyer’s house to collect money owed to him from the sale of narcotics and guns. The debtor’s was named Pete, and when he saw Steve come charging onto his lawn he immediately pulled a pistol on him – one of the very batch for which Steve came to collect his due. He wasn’t quick enough on the draw, apparently, as Steve was able to knock the weapon out of his hands. The two then fought, and spent a considerable amount of time rolling around on the ground. Police files show that the HCSD were aware of this incident, but for reasons that are unfathomable to me, this altercation was never formally investigated by the homicide detectives.

I say unfathomable, but perhaps the reason is not really so complex. No murder takes place in a vacuum, and in this case, the context matters. When the final chapter on this crime is written, it may prove to be that the context mattered far more than is currently thought.

If you live in Houston you have probably heard of the Woodgate neighborhood, to the city’s north. It’s pretty infamous. For many years in a row, it ranked as the number one neighborhood in the city for the highest rate of car thefts. For one stretch of four months back in the late ‘90s, it averaged .9 cars stolen per city block per day. That’s about a car a day, on every block, four months in a row – and those were just the reported thefts. There are at least seven men currently on death row in Texas from this area, though I freely admit that my research on these statistics was more of an afterthought and therefore not comprehensive; there could easily be some that I missed. When Jeff was in elementary school, a friend of his mother’s was murdered two streets over. When he arrived on death row in 2002, one of his first neighbors was a man named Steve Moody, since executed. During a previous stint in population, Moody had celled with the man responsible for the murder of Jeff’s mother’s friend, a weird six degrees of separation style link with Woodgate as the epicenter. On that note, one of my first neighbors upon arrival on the Row was a guy nicknamed Scooter, who was responsible for the murder of an elderly woman, if I remember correctly. His case also took place in this neighborhood.

Woodgate is an uneasy mixture of Caucasian and Hispanic residents, heavily trending towards the latter. Gang fights were daily occurrences, domestic abuse so common as to become sociological cliché. In a perfect world, locations like these would be heavily concentrated upon by the police. In the real world, however, the police are seldom seen in Woodgate, which is perhaps why Steve Herrera never needed to develop subtler business methods. It is surely true that when presented with the crime scene at the Herrera household on that morning in April of 1999, Detective Curtis Brown and company must have first thought: crap, the entire neighborhood is a suspect. That would be a convenient and perhaps understandable excuse for the corners they cut in their investigation, but it would also be too easy of a critique. I shall not condemn Brown for being an incompetent and corrupt police officer. I think, rather, I shall simply let him condemn himself.

Jeff’s upbringing in this caustic social brew was not easy. Fighting and crime were the ways of life in Woodgate, but he somehow managed to graduate high school without a criminal record. By his own admission, he was not a stellar student, but he kept himself out of trouble and made it through. After high school, Jeff joined the Marines, earning a specialty as a machine gunner. He also manned one of the front gates at Camp Pendleton in California, where he couldn’t seem to get the bigger picture that you do not arrest Colonels for drunk driving. His time as an MP was therefore understandably short.

Upon returning to Houston after being honorably discharged, Jeff’s specialty seemed to be snorting cocaine and frequenting strip clubs, not to mention fighting with his two ex-wives. He found work as a manager of a World’s Gym, and later as a paving contractor. Steve Herrera was a friend from Jeff’s elementary school days, and upon Jeff’s return from the service they began hanging around together again. Jeff does tend to gravitate towards friends with oversized personalities, and based off of everything I know about him and have read about Herrera, I can see this mechanism at work in their friendship. The two shared the dream of owning a dance club and would speak of this often. Steve’s cocaine business provided them with disposable income and the connections to make mountains of money very quickly, the only version of a crowd-sourcing campaign available in their world. All they needed was one big score, they reasoned, and they would be set.

That score came about when Steve met a “jacker” who was about to put six kilograms of nearly pure cocaine back on the market. Jackers are the cowboys of the drug underworld, the pure psychos. Jackers don’t bother to build fabrication facilities or distribution networks. No, instead, they simply find other drug dealers, destroy them, and resell their product. It’s a 100% pure profit move, obviously. And just as obviously, dealing with a jacker is also 100% pure craziness. The identity of Steve’s jacker is one of the largest holes in my research, a gap which somewhat haunts me. I know that the FBI agents who were later brought in on this case were convinced of his existence; whether or not they ever identified him is knowledge that Uncle Sam has deemed to be off-limits to we poor mortals: My repeated FOIA requests on this matter were all rejected on purely administrative grounds. I also know that the HCSD never bothered to investigate this facet of the case, meaning that crucial leads available immediately after the killings were lost. As to why they neglected to follow this investigative pathway, I think the answer will become obvious in short order.

In order to purchase the cocaine, Steve told Jeff that they needed to amass $96,000 as quickly as possible. He reasoned that they could easily double their money by cutting the cocaine, putting the dream of their nightclub within reach. The 96K was a problem, of course, as neither of them had anywhere close to that sort of disposable income. After some thought, Jeff ended up going where most potential small business owners go when hoping to get a loan: the bank. Only when he showed up, he didn’t bring a business plan and paycheck stubs, and he didn’t speak with a loan officer.

Over the next three weeks, Jeff robbed six banks. The ease with which these robberies were accomplished seems almost comical to me, and it is a wonder that this sort of crime is not more widespread. Since Jeff had given his Chevrolet Blazer to his girlfriend, he borrowed his mother’s car, put on a baseball cap he had purchased from the Treasure Island Casino in Las Vegas, and simply strolled into the banks and waited in line. When it was his turn in front of a teller, he handed them a note that read: “This is a robbery.” He never carried a weapon. As the teller filled envelopes with cash, Jeff would tell them not to report the robbery for fifteen minutes; the police and media quickly and breathlessly gave him the rather obvious title of the “15 Minute Bandit.” On that first day, he netted $9,690 of Bank One’s cash. All told, Jeff took in over $48,000 from his six robberies, easily fulfilling his obligations for his half of the drug money.

I think it is important to pause for a moment in order to reflect on a very common component of wrongful convictions. Yesterday, I tried to stress the role that our visceral reactions play when an innocent person is sent to prison. Of nearly equal importance is this: the vast majority of such wrongfully convicted persons really are guilty of having committed a criminal offense at some point in their lives. Given this, there are those who would remark, hell, who cares if this defendant isn’t good for this particular crime; they did other stuff so you might as well string ‘em up. (Indeed, in the present case ADA Siegler would tell one of Jeff’s attorneys that “if he didn’t kill Herrera and Tirado, he must have killed someone else,” so it “all comes out in the wash.”) Aside from the lazy and repugnant qualities of this view, it also allows the real perpetrator to remain on the streets, potentially creating more misery. Who could possibly even begin to calculate how much pain has been allowed to come to pass due to such justifications on the part of law-enforcement? Even a rough estimate qualifies this as a tragedy.

It is easy enough to see why it is common for criminals and former criminals to be wrongly convicted at far higher rates than individuals with no such history. When we know that Joe has convictions for shoplifting, we watch him carefully when he comes into our bodega. If something comes up missing, he becomes the instant suspect. Past behavior is usually indicative of present and future behavior, so we feel justified in our suspicions. Prosecutors are people too, and I truly believe that many wrongful convictions stem from honest ADAs being blinded by this sort of thinking. They start from a presumption of guilt and work backwards to interpret the facts through this analytical lens. As you will see, however, that is absolutely not the situation in Jeff’s case. In this situation and many like it, the prosecutor used this bias in the jurors to send an innocent man to death row, and she did it knowing full well that her evidence was fabricated. The fact that Jeff robbed six banks was one of the two nails that the prosecutor used to pin Jeff to the wall, and I ask that you keep it in mind. It is important, as his connection to these robberies is the source from which everything follows.

The evening before the murders was a busy one for Jeff and Steve Herrera. They spent the first few hours of the night drinking and snorting cocaine. Customers would occasionally drop by, lured by the “open for business” sign that was the open garage door. Several runs to the nearest gas station were made in order to purchase beer. At around 10 p.m., Steve’s brother-in-law, Victor Martinez, came by the house in his white Ford Escort. Already drunk, Steve bragged to him that he had $84,000 in cash and kept talking about the dope deal which was imminent. Jeff was concerned about this, and also worried that they were still $12,000 short of the sum required by the jacker. Steve confidently told Jeff that “this was taken care of.” I can find no reason for why the police didn’t take Victor Martinez in for questioning, or for not investigating the party or parties that were to supply the additional 12 grand. This last question is potentially important, because if Steve had asked someone else to be a minor investor in his scheme, this third party might have known about the rest of the money and the timetable for the purchase of the cocaine. Because the drug connection was not properly investigated, we will probably never have answers to these questions.

After drinking for a spell, the three revelers decided to go to Rick’s Cabaret, where they continued to drink and snort cocaine until around 2 a.m. On the way to the strip joint, they stopped at a Jack-in-the-Box restaurant for some food. Jeff was pretty wasted by this point, and he ended up shooting ketchup from the counter dispenser onto his shoes. He wiped this off with a napkin, but some residue would remain. There is really nothing funny about this case, but for those who tend to search for the comedic elements of life within the tragic, this ketchup stain is probably your best option. For me, it would come to symbolize the gross ineptitude of the detectives in this case. At any rate, after the trio left the strip club, they drove back to Steve’s place (somehow) and continued to party. At around 3:30 a.m. the three smoked a joint and Martinez left. Nilda began to get irritated with Steve and his behavior at around 4 a.m., so she asked him to leave.

Their relationship was a stormy one, and this was not the first time that Nilda had asked Steve to get lost. She had threatened to call the police on many occasions, and had just had him arrested for domestic violence the week before the murders. She was something of a pro at giving him the boot, so her threats were not idle ones. Steve was too inebriated to see how this might be problematic for their deal, so Jeff offered to go in and calm her down. Steve contented himself with taking some shots of liquor, shooting pool, and calling his brother on the telephone. His brother would testify that Steve had run out of cocaine and bothered him incessantly during the morning hours to bring him an additional supply. It is not currently known to anyone if he ever complied with this request.

That Jeff had the sort of relationship with Nilda that he could calm her down from the ledge of calling the police on Steve was the second major nail the prosecutor would use to pin the crime on him. The two had become very close, having many “deep talks” which bothered Steve. Jeff had even brought her an expensive housecoat from Las Vegas, which she was wearing that evening. The relationship had only recently turned sexual. I will have more to say on this subject when I describe what took place at the trial, but for the moment it is sufficient to say that after Jeff had convinced Nilda not to call the police she performed oral sex on him. He was too inebriated to participate, and in any case their tryst was interrupted by a sound that they believed to be the connecting door to the garage being closed. Jeff returned to the garage, deciding to call it a night. Having no vehicle, Steve agreed to drive Jeff home. Through they lived only a few miles apart, I have no idea how they managed to make the drive without killing themselves.

When they arrived at Jeff’s parents’ house, the two made a ton of racket, laughing and joking around. They were so loud that they woke a neighbor’s daughter, Christina Garrusquita. Being the eldest daughter of a large Mexican Family, she was rewarded with her own room right at the front of the house that happened to look out immediately upon the Pribles’ driveway. She knew who Steve was, and was able to identify his vehicle. She was rather insistent about this fact, because a few months prior to the murders some of the neighborhood kids had hit Steve’s car while playing kickball. He subsequently cussed them all out, and she had not forgotten him since.

And it is here that I may as well begin the sorry cavalcade of shoddy detective work in this case. During their investigation, Homicide Detectives Brown and Hernandez spoke to this neighbor. Given that her information a) placed Jeff at his place of residence at a very late hour, b) established that his behavior was consistent with a deeply inebriated man, and c) showed that Jeff and Steve had had a non-acrimonious parting, young Christina was considered to be what is called an “alibi witness” in legal circles. Despite these facts (or because of them), Detectives Brown and Hernandez did not ask Christina to sign a formal statement at the Homicide substation at Lockwood and Navigation, as they did with a few other witnesses. Worse, they did not turn over even a notification of this interview to Jeff’s trial attorneys – a violation of the discovery order filed in the 351st State District Court. Worse still, the only reason the defense knew of this alibi witness’s existence at all is because defense attorneys Wentz and Gaiser happened to go to Jeff’s parents’ home and noticed that the window at the adjacent house provided a perfect view. At trial, these two seasoned detectives would give what amounted to “keystone cop” explanations for this omission from the record. Brown claimed that he couldn’t find his notes, and Hernandez stated that he “didn’t make any supplements or notes” because he “felt Detective Brown was going to be making the notes for both” of them. In fact, conveniently, they could not even recall where this witness lived or even her gender. On 11 October 2001 – the Friday before the trial began the following Monday – the lead prosecutor was still claiming that she did not have identifying information regarding this witness.

It’s really not hard to speculate why Detectives Brown and Hernandez acted in this fashion, and why the prosecutor played along. Within hours, the two had already decided Jeff was guilty, and everything done after that point was completed in such a manner as to construct this narrative. That they did this is reprehensible. That they did this without actually bothering to do any investigation on anyone else is beyond reproach.

After Jeff parted ways with Steve for what would be the final time, he went upstairs to his room. He made himself a bath, dunked his head in the water to clean the cocaine from his nasal passages, and went to bed. All of the clothing he wore that night was laid out on the floor next to his bed. After he woke up the next afternoon at around 2 p.m., he dressed and went downstairs. As his son was opening up the front door to go outside and play, Jeff saw detectives Brown and Hernandez coming up the walkway. They identified themselves as detectives and asked him if he would accompany them to a substation for a chat. Believing that Steve must have told someone about the bank robberies, he agreed to go with them, not wanting to cause a scene in front of his son.

Knowing what I know now, the die was pretty much cast at this point. I’ve been deliberately fair in my recounting of the facts in this case to the state, attempting to paint a picture for you that showed that Jeff Prible could have been a viable suspect. I did this because I knew there would be a point in the story where all pretense of an honest investigation would end, and I didn’t want to leave the impression that I am “anti-cop” or anything like that. Unfortunately, from this point forward, all I have to show you is a justice system so perverted that no defense or justification can be proffered.

When Jeff arrived at the Lockwood homicide substation, he was informed that Steve, Nilda and the children were dead. He was asked about the evening before, and about the time he and Steve parted ways. He was specifically asked about the clothing he was wearing, and when he told them that they were on the floor of his bedroom next to the bed they asked if they could send someone to collect them. He gave his consent instantly. When they asked for a DNA sample, he gave them three: blood, hair and saliva. When they asked him to remove his clothes so that they could take detailed photographs of his body, he consented. At trial, Detective Brown would somehow claim that he had not known about and had never seen these full-body photographs. They would turn out to be important for two reasons. First, in photographs of the crime scene, there are bloodstains on the wall near to where Steve was shot that indicated that he had fought with and wounded his assailant. The sort of wounds consistent with this degree of blood loss would certainly not have healed for many weeks, let alone in less than twelve hours, yet Jeff’s body bore no wounds. Additionally, the primary accelerant used in the fire was Kutzit,, an agent used to dissolve tile glue. It has a tendency to stain the skin, so anyone tossing it about a room in an attempt to start a conflagration would have splotches on their skin and clothes. Neither Jeff’s skin nor his clothing bore even microscopic traces of this liquid. Worst off, even though the blood stains on the wall were highly suggestive of an altercation, no forensic samples were ever taken from this source. When asked at trial about this horrendous oversight, Detective Brown’s answer pretty much said it all: he simply smirked and said “poor detective work”.

I should reiterate at this point that none of the above consisted of speculation or even a “friendly” reading of the facts. All of this is in court documents that any one of you can obtain on your own (though I will provide many of these for you at the end of this series). I just thought that I should point that out because if you think the story is bad now, just wait. We haven’t even touched on bad yet.

To read Day Three click here

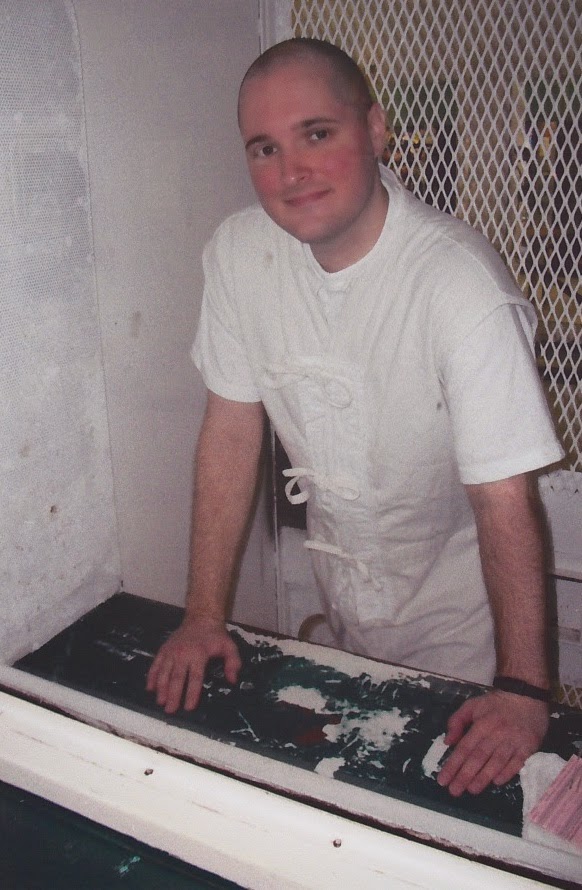

Ronald Jeffrey Prible 999433

Polunsky Unit

3872 FM 350 South

Livingston, TX 77351

3 Comments

Anatomy of a Wrongful Conviction – Day Three - Minutes Before Six

April 28, 2023 at 6:41 pm[…] 0 By Thomas Bartlett Whitaker To read Day Two click here The murders of Steve Herrera, Nilda Tirado, and their three children were discovered shortly […]

Anatomy of a Wrongful Conviction – Day One - Minutes Before Six

April 28, 2023 at 6:35 pm[…] prosecutor played the tune, but it was you who were dancing to the beat. To read day two click here Ronald Jeffrey Prible 999433 Polunsky Unit 3872 FM 350 South Livingston, TX 77351 Thomas […]

Unknown

May 31, 2014 at 10:57 amThis is amazing, I feel like I reading a fiction but sadly it's true life.