By LSD Gonzalez

“Suave!”

“Suave!”

“Suave!”

“Mira aqui!”

“Tell us why you committed that crime!“

“Are you sorry you’re going to prison for life?”

“Suave!”

The reporters’ voices still reverberate in my head. Although it has been twenty-eight years, it seemed like it was only yesterday.

Standing at my cell door for count, I looked up at the raindrops creeping into my prison cell through the concrete walls. This was supposed to be the end of the road for me, but it was more like the beginning of a new start on life. I stared into the metal plate on the wall, which served as a mirror, and noticed a few gray hairs. Damn! I’m getting old up in this place.

It was June 25, 2012, and I did what I had been doing for the past twenty-eight years after the 4:00 p.m. count. I took six steps and sat back on my bed, immediately feeling the metal as it seeped through the thin mattress, causing a pain in my ass. The mattress might as well not have been there. I shook my head as I stared at the T.V., listening to CNN News.

The United States Supreme Court today ruled that juveniles

who committed a crime before the age of eighteen can

no longer be sentenced to life in prison. In doing so, it

would be considered cruel and unusual punishment,

an Eighth Amendment violation. This is Don Lemon,

reporting for CNN News.

Upon hearing the news that would change my life forever, I did something I had never done before. For the first time, I sat down in front of my word processor and began writing my life story.

******

The social worker behind the desk wasn’t a friendly person. My mother knew this, but what choice did she have? One way or another, she was going to feed her six babies.

My mother swallowed her pride as she approached the desk. I stood by her side, watching the river of pain flow through my mother’s veins, and I blamed my father for deserting his family. He decided his life would be better if he turned his back on us. As 1 stood beside my mother, I could see tears forming in her dark brown eyes.

“Son, don’t worry, things will get better one day,” my mother whispered into my ear. Those words blared in my ears like the sound of a trumpet blast as I tried to grasp the concept of being poor, fatherless, and getting ready to watch my beloved mother beg for some assistance from the welfare system that’s skillfully designed to tear families apart.

When the social worker behind the desk decided to attend to my mother, she gave her a what-do-you-want look. My mother, not knowing enough English, had me interpret for her. That was the day my hatred towards the system blossomed. That was the day I understood that a person didn’t have to use racial slurs to call me a spic. Action speaks louder than words.

The social worker didn’t have to say a word for me to understand her hatred towards my mother.

I couldn’t come to a rational understanding as to why this lady, who was fluent in Spanish, wanted to make my mother feel inferior. After an hour of me trying to explain to her what my mother was telling me to explain to her, she decided to speak Spanish directly to my mother. Now the process began over again, and a whole new round of personal questions in front of the other people began.

“Ms. Beggar, why are you here today?”

“Because I need help. I don’t have any money to feed my babies,” my mother responded in a calm voice.

“Where is their father?”

“In jail, probably dead. I don’t know. His ass hasn’t been around for a long time.” My mother tried to speak softly and answer the question in a civilized fashion, but the social worker loudly repeated what my mother was telling her – with a grin from ear to ear as if it was funny – in what appeared to be an effort to embarrass my mother. She wanted to know everything about my mother, not just her address, social security number, or date of birth. She even wanted to know the last time my mother had sex or if she had a boyfriend. The social worker was acting as if she was the supreme ruler of the welfare system. She became more indignant when my mother started asking questions about benefits that my mother thought she was eligible to receive.

“Ms. Beggar, if I were you, I would stop having babies. I really hate to see my tax dollars go to waste. Your babies probably are going to end up like their father, in jail or dead,” the social worker said with distain in her eyes.

“You have no right to speak to me in such fashion,” my mother said.

“Listen here, Ms. Beggar, you better be happy I’m doing this much for you. Normally I would turn you down for any kind of assistance. Beggars can’t be choosy,” the social worker said loudly as she pushed a piece of paper in front of my mother to sign.

“What am I signing here?” my mother asked in Spanish.

“Can’t you read?” the social worker responded with an attitude, placing her hands on her hips.

“No, I don’t know how to read,” my mother replied with shame in her voice.

“Ms. Beggar, I hate to be the one to tell you; this is America! So I suggest you learn the English language and fast. The next time you show up here, you better know English, because if you don’t, you will not receive any more assistance.”

After my mother signed the piece of paper that was put in front of her, the social worker pushed a white envelope towards my mother

Gracia Dios Mio!

My mother picked the envelope up in a quick motion and ripped it open like fresh meat in a lion’s den. Her eyes grew large when she saw what was inside.

“I’m supposed to feed six kids with a hundred and sixty-five dollars?” my mother yelled in Spanish, walking out of the welfare office, feeling as if she had been raped of her dignity for a hundred and sixty-five dollars of emergency food stamps.

“Son, look at me! Never again would I degrade myself to these people. Never! I want you to understand one thing. In life you gonna have to learn how to survive on your own. You better never beg these people for shit! Always remember that. Your no-good daddy left us broke, and now it’s up to me to take care of you and your sisters. From now on, I’m your father and mother. Do you understand me?”

“Si, Mami.”

Even at the age of eight, I understood every word my mother was injecting into my head. I felt her motherly love and the pain she was feeling because she wasn’t able to take care of her kids the way she wanted to.

Two weeks later, the welfare agency sent an investigator to our four-bedroom South Bronx apartment to see if my mother had a man in the house. The pale-faced lady roamed freely through our apartment as if she owned the place. Her job was to report any findings of child abuse, and she was authorized to remove us from the house if she found such evidence. She tried to interrogate and coerce my sisters and me into lying about our mother.

“Listen! My name is Diana Hicks, and I’m here to ensure you and your sisters are safe. So tell me, does you mother abuse you? Does she feed you? Does she bathe you? Does she do drugs? Trust me, whatever you tell me will remain a secret. I just want to make sure you and your sisters are being properly treated. I’m a good person.”

“My mother is a good person, too,” I replied in a childlike voice.

“But does she abuse you?”

“No!”

“Has her boyfriend ever touched you in your private parts?”

“No.”

“Be honest with me, you little nappy-hair spic!” the pale-faced lady whispered into my ear, turning red in the face.

I just stared at her without blinking an eye. I felt like I had been betrayed by the system that was supposed to help families in need.

Shame!

For a mother that swallowed her pride so that her seed could have a better chance at life…

Hurt!

Even at the age of eight, I was becoming accustomed to suffering with clenched teeth.

Everything about the welfare system was organized to make clear that as the government, they were in charge of every aspect of one’s life once you accepted their assistance.

My mother came from a town in Puerto Rico called Santurce. She was the product of a rape, which automatically made her the “Black Sheep” of her family. Her mother was a white-skinned, blue-eyed, blonde-haired woman with an undisputed hatred for black men. Every time my grandmother stared at my mother, memories of her rapist would inflame her mind to the point where she would beat my mother until she would choke on her own blood. She was called many things: stupid, retarded, trash, a fat savage bastard-until one day my grandmother couldn’t stomach her own daughter anymore. She took my mother to a Catholic Church and left her on the steps with a sign attached to her neck that read:

This child is the scum of the earth.

The product of a rapist.

I did what I could for ten years.

Now I’m forfeiting parental rights.

At the age of ten, my mother became a product of the foster-care system, where she endured countless rapes at the hands of her caretakers. The streets of the South Bronx became her safe haven.

With no education or family members to care for her, my mother survived by selling her innocence on the streets.

At the age of 16, history repeated itself. My mother was brutally raped by a police officer in the Bronx.

“You dirty, little hooker. You’ll either chew me up or I will take you to jail.”

Dios Mios! Please don’t let this man rape me. “Please stop!” she pleaded.

“Don’t act like you’re scared. I been watching for a while now. You just can’t hustle out on these mean streets and not pay any taxes. Consider me sexing you your taxes. Now, get in the car on your own before I beat your dumb ass into the car.”

“Officer, please stop!”

He smiled.

Who was this man? This was supposed to be an officer of the law who had sworn to protect and serve. Instead, he was in the process of raping her.

“Please, officer, don’t rape me,” she sobbed as tears escaped her eyes.

“You little slut, I’m gonna mold you into a money~making machine. You gonna be my bread-and-butter. Let me remind you, your photo is everywhere! You can either let me get a taste of your sweet innocence, or I can arrest you and take you back to foster care. I know you don’t want that.”

“Officer! Are you outta yo mind?”

The officer got out the car and bent her over the car. He lifted her leather miniskirt all the way up as he helped her slip out of her panties.

“You naughty girl,” the officer said as he stood behind her, positioning himself to enter her sweet innocence.

“AHHHHHH!” She screamed when she felt him enter her wound.

By every sense of the word, my mother was nothing society at large should care about. She was just another statistic; another dark-skinned Latina with six children from six different baby’s daddies; another uneducated woman lost in the Promised Land. But to me, she was a heroic woman, and like her mother she courageously gave birth to the product of a rape, when she could’ve easily aborted, sparing the child a similar fate.

Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat to a white man and is held as a historic figure of the civil rights movement.

Harriet Tubman provided a path through the underground railroad for runaway slaves and is viewed as a historic figure.

Lolita Lebron spent twenty-five years in prison because of her beliefs and she fought for the independence of Puerto Rico, and she is viewed as a historic figure in Puerto Rico.

Throughout history, women have been the backbone of some of the major struggles in America. Yet, we don’t acknowledge the everyday, single, struggling mother with the same respect we give historic women.

There’s no difference between Rosa Parks, Lolita Lebron, Harriet Tubman, and the average Latina or black woman in the ‘hood who must assume all the responsibilities of a father.

There’s no difference between single mothers who must protect their sons from the evil grips of America-such as the justice system, police brutality, or the George Zimmermans of America and those heroic women who fought for social justice.

My mother was the product of a rape, an uneducated Latina woman, and a single mother of six children; moreover, she struggled against the injustice of one of America’s racist institutions: the welfare system. She made sure her babies were well fed, well-clothed, well taken care of, and well-educated on a street level. My mother ventured across the landscape of New York City and buried her teeth into the throats of those who viewed her as a social outcast.

Being raised in the South Bronx gave my mother lessons on how to survive. Realizing the monthly check the welfare system provided wasn’t enough to take care of her family, she decided to hook up with a few corrupt city officials in the public housing department.

Around this time, New York City was beginning to develop Section Eight housing apartments for low-income families. The waiting list was long, but for the right price, you name could be bumped up on the list. These corrupt officials were selling the applications, and my mother was their direct link to the streets and the families who desperately were seeking a better place to live.

I remember times when my mother’s apartment used to be filled with people from all over New York City. Some we knew. Others were just there for the first time, dropping off their payment, hoping to improve their living conditions. After every apartment my mother sold, she celebrated with a bottle of American champagne. Selling Section Eight apartments had paid off for my mother, with unintended results.

After a few years of living ghetto fabulous, my mother learned the FBI had our apartment under surveillance. Someone alerted the FBI that my mother was selling Section Eight apartments. Since jail was not an option, my mother went on the run, forced to do what she vowed never to do, turn her back on her seeds.

“Son, Mami must go away for a little while. Now you’re the man of the house. It’s your responsibility to look after your sisters. The streets love no one; always remember that. Only the strong will survive in these jungles. You could either be the victim or the victimizer. Always know there’s a bitter with the sweet.”

******

My mother’s words still resonate in my mind today, twenty-eight years after they were whispered into my ear. After the 4:00 p.m. count, guards rushed onto C-Block, responding to a cell fire.

“Mr. Dees, don’t do this! Put the bottle down, now!” Sergeant Evilsky commanded.

“Get the fuck away from my cell if you don t want to get burnt, Mr. Dees replied.

“Why go out like a nut now when the Supreme Court said today you can get out?”

“I don’t want to go out! You motherfuckers took sixty-two years of my life, now you want to kick me out. Nah, I’m a ward of the state till the day I die,” Mr. Dees said as he spread the gasoline that he had in his shampoo bottle on his cell door, preventing the guards from entering his cell.

“All inmates open your cell windows. You will not be let out of your cell,” an officer yelled over a loudspeaker.

I silently took all this in. I kept typing.

“Suave! I guess that’s one less convict we have to worry about releasing back into society. Your old head burnt and hung himself,” correctional officer Lucifer said with a smile as he pushed Peter Dees body on a gurney off the cell block.

“Son, there’s always a bitter with the sweet. Now isn’t the time to lose focus. Some people can’t handle reality. Their situation can be so harsh at a particular moment that giving up all hope may be the best thing. If they want to lay down and die in prison, leave them laying where they at.”

Hearing my mother’s voice in my head brought a smile to my face. I turned my word processor off and lay back on my bed, listening to the radio, when suddenly my favorite song came on, “I’ll Always Love My Mama” by The Intruders.

Sometimes I feel so bad when I think of all the things I used to do

My mama used to clean somebody else’s house

just to buy me a new pair of shoes

I never understood how mama made it through the week

When she never, ever got a good night’s sleep

I’ll always love my mama…

From the Hood To The Prison Pipeline is a series, so stay tuned for the next installment.

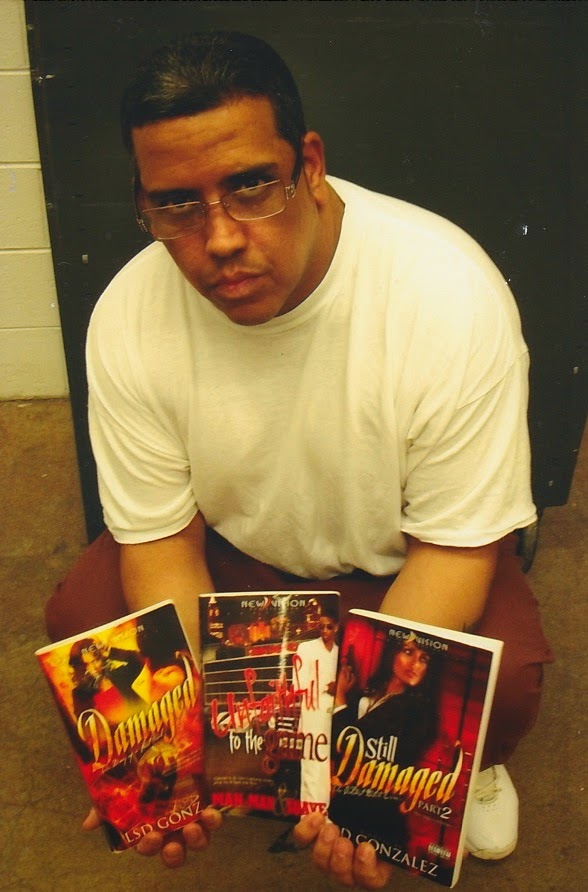

LSD (Luis Suave) Gonzales is a Juvenile Lifer, incarcerated for over 27 years. He attends Villanova University and is two classes away from a Bachelors Degree. He is president of the Latin American Culture Exchange Organization (L.A.C.E.O.), a member of the United Community Action Network (U-CAN) and one of the founders of the Education Over Incarceration (E.O.I.) scholarship. He is the author of five critically acclaimed novels and is an artist and poet.

Luis S. Gonzales

LSD’s artwork can be viewed here

No Comments

Unknown

June 27, 2018 at 6:08 pmHeard him speak in person. Great man. So happy hes so successful with the reintegration program at Nu Stop.