To read Chapter One, click here

The Three G’s

In many respects, it was still the Fifties in Little Italy. And that version of the Fifties wasn’t a hell of a lot different than the Forties or even the Thirties, which except for the clothing styles and the music, could have passed for the nineteenth century. And that was OK with most of the residents, capiche? It was an insular society that, conversely, conducted much of its business on the streets. The presence of the Mafia was everywhere, but troubled no one; in fact, the blocks between Houston and Canal, the Bowery and Broadway, were the safest areas in the city. Romantic couples and voracious potheads with the late-night munchies could stroll without fear of mugging from the West Village to Chinatown, judiciously detouring to the opposite side of the street when they passed the Ravenite “Social” Club where beefy cats sporting bespoke suits and day-or-night sunglasses lurked menacingly. In a dangerous city, Little Italy was an unlikely oasis of safety. Plus, the food was great.

At the corner of Houston Street (“House-ton, not youse-ton!” Sam had corrected Sean the previous year), they waited for the light. Minuteman shapeup was on the other side of the busy four–lane highway, a crude image of a musket-toting Revolutionary War soldier painted on its front window. Underneath the caricature was the stencilled announcement, “Temporary Employment–We Pay Daily’ “Sam regarded the sign and shook his head in disapproval. “Working as a human wheelbarrow isn’t a hip way of making bread, man. You gotta, like, latch on to an easier gig.”

Sean had been raised on a farm and thought the jobs he had worked at were fairly easy. Mostly, he shovelled piles of broken-up plaster and cement block dividing walls into steel carts, rolled them to a freight elevator, pushed them out to the sidewalk where they were dumped on the street and then reshovelled into a dump truck. When that was filled, he and the other workers filled the next one. On some jobs there was only one truck, and when it was full, Sean and the other laborers lay on their backs on top of the load, watching with a thrill the tall spires of the city scratching the deep blue back of the universe.

The hiring agency paid minimum wage and provided a dollar carfare up front for a bus or subway ride to the job site–twenty cents each way, with sixty cents left over for lunch. Workers were paid by check at the end of the day and tax deductions were taken out, although Sean hadn’t received at the end of the previous year a W-2 form to file with his tax return. The checks could be cashed at a local bar for the price of a drink, presumably to cover the expense of the cashing privilege. The real reason, of course, was to tempt the worker–often a down-at-his-heels booze fighter–into drinking up his pay check at the bar, which was in cahoots with if not actually owned by Minuteman. It was a classic Big Apple hustle in which the cost of labor was ingeniously recycled in a closed system and returned to the employer two-fold: Once in the profit earned by the difference between the minimum wage paid out and the near union rates charged to the demolition companies; and twice in the hyper-inflated price of a bottle of Rheingold bought by the worker. It was a smart scam, Sean had to admit, but the second part of the equation didn’t balance in his instance–one beer was plenty for him.

“Aw, it ain’t bad. I get to see the city,” Sean offered as an excuse.

Sam shook his head and frowned. They travelled all over the city anyway in Sean’s ’50 Chevy that he had brought with him in March after wintering with his parents in Pennsylvania and working at a box factory to earn travelling money.

“Well, if you dig it, then I guess it’s OK,” Sam grudgingly allowed. “But it isn’t cool. You’re working for the system. You gotta make the system work for you, like Billy does.”

Billy! Sean thought. Who’d want to be like him?

They crossed Houston against the light, sidestepping traffic, and entered the beating heart of Little Italy with its corner bars and pasta restaurants and small groceries with outside fruit stands. Sean loved the old world ambience, the screaming kids underfoot, the traffic creeping slower than he walked. He thought of Billy’s solitary existence in an illegal storefront on East Second Street between Avenues B and C, denned up in a beastly hovel on a godforsaken block on which a hundred thousand dreams had briefly flickered and perished.

Sam zapped across the street to examine a discarded dresser on the curb, but he hadn’t forgotten Billy, not for a minute. “Dig it, man, Billy collects a welfare check every two weeks and the city pays his rent and utilities. Plus, he gets food stamps he sells for drugs or extra bread. Wow, man, now that’s the kind of gig you gotta land! Then you’ll have time to live, instead of slaving for a living.” He assayed the pulls with a practiced eye, and then used a dime to unscrew them. “Outta sight, man! Hand cast brass! They just don’t make shit like this anymore!”

As Sam harvested his treasure, and the locals watched warily, Sean considered Billy’s made-in-the-shade life. Billy had once been on the “set” with many of the original Beats, but was now reduced to a burned out relic. Unlike Ginsburg or Kerouac, he had never known nor deserved any fame. Like William Burroughs, Billy had once had a junk habit–now “controlled” by methadone–and was gay; no great drawback among the hipsters, but hardly a ticket to success in the pre-Stonewall days. He lived sans shower, tub, or even electric, in a candle-lit hoorah’s nest crammed and cluttered with the random detritus of his wasted life. Balding and sallow, he hunched amidst his dubious possessions, drawing pen and ink silhouettes of winter-bare trees conjured to life by his morbid imagination. One would be more likely to encounter a raccoon or an owl at a Sunday morning be-in at Tompkins Square Park than to witness him sketching plein-air on a sunny afternoon. Darkness seemed his friend.

Billy was friendly enough and always seemed glad to get company, but the gloomy ambience of his hovel and his frequent uncomfortable silences made conversation difficult. After exchanging a few laconic pleasantries, most visitors couldn’t leave quickly enough. Once when Sean closed Billy’s door, he saw Billy’s eyes close, too, as if he were going into suspended animation until the next visitor came knocking, bearing news from a faraway land where the hobgoblin of salvation that Jack and Neal had chased ragged across the continent and never caught was waiting patiently just for him.

Sam unscrewed the last of the brass pulls and put them in his pocket. He had no conceivable use for them, or a likely buyer. They would join the existing accumulation of rubbish in his loft, a farrago of useless knickknacks, curios, odds and ends of oddball oddities, and just plain out-and-out junk he had scavenged from every alley and abandoned building in lower Manhattan. In Sam’s entire loft, a space maybe twenty feet wide and thirty-five feet long, there were no dressers, cabinets, or closets, not even a table. There was a toilet and shower in the rear, and two sheetless double beds, separated by a ratty blanket hanging from the ceiling. Dirty clothes lay where they fell, or were tossed on a pile near the toilet. Periodically, when he ran out of clean or semi-clean clothes, Sam threw them in a navy surplus duffle bag, grabbed his guitar, and schlepped over to the Second Avenue all-night laundromat. But there weren’t many clothes to start, because he never wore underpants or even socks most of the year. And since he rarely worked, his tee shirts and dungarees took quite a while to reach the must-wash stage. What the hell, he reasoned; society considered him a filthy beatnik, so why fight it?

The door pulls, saved because they were old and made from brass (the opposite of “new” and “plastic”) would be carelessly tossed under the bed or placed on his archetypal beatnik bookshelf made from planks and bricks “appropriated” from a job site. Eventually they’d end up on the floor where they’d be stepped on, cursed at, and kicked against the wall to swell the mounting scree of rubbish and forgotten pack rat treasures dragged home by the head pack rat, Sam, the undisputed pooh-bah of urban gleaners. Despite the clutter, however, there was nary a cockroach and only an occasional mouse. Neither Sam nor the Bonners cooked or even brought home take-out. They ate at seedy diners and cheap Chinese restaurants off the tourist track. Actually, they ate damn little–there were no fat beatniks.

Sam delivered an in-depth exposition on the differences between brass and bronze as they walked, expounding upon the ratios of copper and tin that each required. Before Sam could drag him into a copper mine, they arrived at Canal Street, the cross town artery between the Holland Tunnel and the Manhattan Bridge. Chinatown began at Canal Street, and except for the tourists it was as exotic as Shanghai and as crime free as Little Italy. It was ruled by the “Tong,” who preferred anonymity–no macho posturing outside “social clubs” for them.

The various businesses along Canal were a capitalistic interface between cultures, New York City in the raw. Not only did everything have a price, it was negotiable. Jaywalking on Canal was tantamount to Russian roulette, so they waited for the light and crossed safely with the herd. With an alert eye for bargains, they nosed in and out of the numerous second, third, and fourth-hand junk shops that were strung along Canal like cheap beads in a tawdry necklace. They worked the shops methodically, quickly scanning the stacks of hardback books for first edition novels by famous authors. Sam rooted through crates of machinery parts, hankering to discover the lost sprocket of satori or perhaps the skeleton key to the secrets of the pyramids, all the while scoping out the clothing racks for any cute hippie chicks seeking sartorial enlightenment in one of Granny’s old cocktail dresses. But they had no luck; they kept bringing in dry holes; no bonanza today–so sorry!–and were ready to hit their favorite dim sum shop for a coffee and a few tau shu baos when Sean hit paydirt.

“Hey, check this out! The perfect dope stash!” He held up a round wooden canister with a matching lid. It resembled a fat, pine lipstick case.

Sam opened it, closed it, and counted how many were in the box. He asked the old Jewish owner watching them carefully from his stool how much they cost.

“A quarter apiece,” he replied.

There were sixteen containers in the box, and Sam examined each one, frowning when he spotted imaginary defects. “Some of these are cracked,” he bluffed.

The man shrugged. “Don’t buy them, then,” he advised.

“A quarter’s too much,” Sam decided. “I’ll give you two bucks for the lot.”

With a sigh, the man got off his stool and shuffled over to the bin. Counting the tubes, he mentally weighed the canisters against an imaginary poke of gold. “Three bucks, and I might make enough for carfare home.”

Sam stifled a laugh. A twenty-cent subway token would take you to the outermost borders of the city, beyond which the maps warned of monsters. The owner probably lived in the second-floor apartment and gouged his other tenants sufficiently to provide a comfortable living. The junk store was nothing more than an old man’s hobby, a distraction that kept his mind off his impending demise.

“Two-fifty, and I’ll even take the bad ones, too,” Sam pronounced, giving the old coot one of his penetrating stares.

“Oy vey!” he exclaimed, throwing up his hands. “Two-seventy-five, and that’s final! Another step closer to the poorhouse I go!”

They pooled their change and handed it over. The old man counted it out, muttering in Yiddish, and handed them a crumpled paper bag. “Bag them yourselves,” he said. “Me, I’m mourning my loss.”

On the way home, Sean asked Sam why he’d bought so many.

Sam grinned. “How many would you have bought?”

“I don’t know. One for me and maybe a couple for you and Mark.”

“See? That proves my point! You’re not thinking like a hipster yet. I would’ve bought fifty, if he had that many and I had the bread.” He smiled at the thought and gave Sean a huge wink.

“Ah, I dig it now! You’re going to resell them!”

“Fucking aye, man! We’ll slap a coat of stain on them and sell them to the headshops for a buck-fifty and make ten bucks apiece. That’s what I mean by making your living the hip way.”

“I dunno,” Sean said, doubtfully, “shouldn’t we lay some on our friends for free?”

Sam shook his Harpo Marx-coiffed head in slow disbelief. “No, NO, NO, man! That’s the hippie way, not the hip way! First, you make a good score, and then you lay a few on your friends. In fact, after we unload these, we’ll try to find some more and up the price, see what the market will bear. That’s what they call ‘hip capitalism’.”

“Shit!” Sean protested. “That’s no different than what the squares do.”

Sam laughed at Sean’s naiveté. “You gotta stop believing that horseshit you read in The East Village Other, man. The difference is that the squares spend their profits on paying rent and car insurance and color TV’s. Hipsters spend theirs on grass and guitars and other groovy shit—the Three G’s, man!” He chuckled at his wit. “Hey, dig it, man! I just coined a phrase!”

Sean laughed, and they continued home. At the hardware store at the corner of the Bowery and Bleecker, Sean bought a half-pint can of walnut stain with almost his last thirty-nine cents and Sam shoplifted a small paintbrush. Back at Sam’s loft, the radio was still playing “The Ballad of the Green Berets,” so they listened instead to a Top 40 station while they stained brown the outsides of the “pocket stashes,” as hip entrepreneur Sam had labelled their “hot” commodity. The rest of the day and evening they watched the stain dry while smoking up some dynamite Panama Red that one of Sam’s come-an-go chicks had foolishly left behind. Around nine or ten, as Mozart’s Piano Concerto #21 played on the classical station, they passed out. Sean had to get up early for the 6 a.m. shape-up at Minutemen’s, but Sam could sleep in–he only worked hip hours.

To be continued…

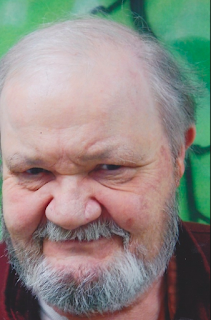

Burl N. Corbett HZ6518

* for more information click here

Authors note: Dreaming of Oxen is a 52-chapter, 556-page tour de force in search of a literary agent or an independent publisher willing to disregard my present circumstances and focus instead upon my art.

No Comments