The prisoners stank. The record doesn’t list many details from the early days of the outbreak, just that one sneering comment about the distastefulness of the wretches brought to face justice on that morning in 1750. Even in London, the largest and arguably the most civilized city on the planet, the prisons were no place you’d care to find yourself. “Prisoners” in those days meant mostly vagrants and debtors. Actual lawbreakers tended to receive far more immediate penalties such as fines, periods in the stocks, or capital punishment. There were roughly 160 crimes for which you could be hung in England at this time, and that rather gruesome figure would swell to more than 200 by 1815. You could swing for pilfering fruit; you could dance in the air for stealing a sheep. None of those marching into the Old Bailey in chains on that morning were guilty of such heinous crimes, though. They were just poor, in debt. They were locked up for being paupers.

They lived in a dark hole of a dungeon, all sexes and temperaments crammed together until someone paid off their debts. Perhaps my favorite description of Newgate, one of Ye Olde Blighty’s most (in)famous prisons, can be found in Daniel Defoe’s Moll Flanders:

… ’tis impossible to describe the terror of my mind, when I was first brought in, and when I look’d round upon all the horrors of that dismal place…the hellish noise, the roaring, swearing and clamour, the stench and nastiness, and all the dreadful crowd of afflicting things that I saw there; joyn’d together to make the place seem an emblem of Hell itself, and a kind of entrance into it.

So, of course they didn’t smell like roses. How could they not reek? What nobody seemed to notice was that there was a sickeningly sweet note added to the usual pong of sweat, grime, and desperation. The death toll from the typhoid outbreak eventually included two judges, an alderman, a lawyer, an undersheriff, several members of the jury, and roughly forty others — including the Mayor of London. Of course, they didn’t call it typhoid at the time. No, this disease was then known as gaol-fever, which I think is pretty instructive: this was a malady primarily afflicting and identified with prisoners. On this occasion, it slipped its shackles and exacted vengeance upon those who created the conditions necessary for it to flourish. Did any of the grandees struck down with this sickness make this causal connection? The record doesn’t say. Given what I know about most humans, I’d guess probably not.

Better question: do you?

Because this is a pretty tidy metaphor for the concept I seem to be valancing lately in these pages, that what happens in Prison Land doesn’t stay in Prison Land. What we learn here, the mercenary inhumanity that infects us, it carries on, it festers. Although I’ve limited my recent writings to behavior assimilated in these halls by prisoners kept in solitary confinement, the metaphor applies far more broadly, perhaps more so than you have given much thought to, unless you are of a historical bent. Hitler’s thugs, Mussolini’s brown shirts, Stalin’s goons: these were revolutions of policemen, using the rhetoric of public safety and order: find a political party with “law” or “justice” in its name, and you will find a pack of fascists (double villain points if you can cram them both in there: howdy, Erdogan). What horrors they brought to the world were an extension of what happens when you reduce people to objects and value rules and laws more than human suffering or even existence. Every thinking prisoner everywhere and everywhen has had a sense of this, of how comfortably some officers slip into the roles of petty tyrant — how this is not a way of looking at the world that can be turned off when someone clocks out at the end of shift. I’ve written this so many times it is starting to sound a bit like a slogan: you cannot have islands of authoritarianism nestled against the soft, chaotic underbelly of a free society without some kind of invasion taking place. The totalitarian mind is its own worst enemy, and this is a secret it keeps from itself by constantly attacking those that oppose it, either directly via violence or politically by arguing that the cure for the inherent messiness of the democratic world is a bit more order, a bit more obedience. After all, it works just fine on a daily basis (for them). To such people, there is always a tendency to desire an extension of that order over more and more aspects of society that oppose what they perceive to be the natural state of things. Cancer grows. That’s what it does. You survive by detecting the tumor early — by getting it out of you. The body politic is no different. Liberal democracy got lazy these past few decades, after the so-called “end of history” dawned in the wake of the USSR’s disintegration. We allowed some awful ideas to survive and now these have evolved and colonized the free world. Witness democracy’s discontent, abroad and at home.

So, too, with the law. The Supreme Court has been in the news quite a bit of late, and not as a result of a broad appreciation for the Justices’ collective sagaciousness. From the Dobs v Jackson Women’s Health Organization case that ended a woman’s right to control her own reproduction cycle, to the West Virginia v Environmental Protection Agency one that hogtied the government’s ability to deal with climate change, the SCOTUS has taken positions that are far outside of what vast majorities of Americans consider to be reasonable — and more importantly, at least to me, outside of the judgments of the overwhelming majority of scientific experts in the fields those cases addressed. I’ve even begun to notice increasing hand-wringing in nonspecialist sources over the expanded use of the court’s emergency docket — the so-called shadow docket, as many in the legal community have taken to calling it. When you think of court rulings, you probably envision a mass of impenetrable verbiage, comprehensive briefings and arguments, and opinions written and signed by the judges involved. Those cases inhabit the merits docket. There is another set of cases, however, where you find judicial orders that are unsigned, unexplained, and entirely devoid of any reasoning. This shadow docket initially came into existence as a means of dealing with routine case management. Major rulings dealing with weighty social issues used to be addressed quite rarely with the emergency docket: it was only used eight times in total during the sixteen years of the Bush II and Obama presidencies. Trump’s court utilized it forty-one times on major rulings, and many in the legal community are starting to wave warning flags about a crisis in legitimacy that might eventually destroy what credibility the court had left at this point.

How nice. I can’t help but to wonder where these analysts have been for the past thirty years, because capital litigants have been suffering under the non-rulings of the shadow docket forever — and by “suffering”, I actually mean: being put to death. Indeed, capital cases are the reason the shadow docket exists at all in its present format. When a state district court sets an execution date, this usually catalyzes a flurry of last-minute appeals. These need to be addressed by the high court, obviously, because unlawful execution would cause “irreparable harm”, the standard for such rulings. I’ve written about this a number of times over the years, how the SCOTUS denies certiorari without any kind of comment on what in every single case is a mountain’s worth of arguments and briefings. You think jurists of an illiberal bent didn’t pick up on the message here? They noticed that nobody really cared in any meaningful way when some scumbag prisoner got hauled off to the medicalized gibbet after this type of non-ruling. They began to wonder where the line was on what other kinds of cases they could deal with in this summary fashion — how much they could redefine the meaning behind that whole “irreparable harm” business. When would people notice that “because we said so” isn’t a proper response to anything in a democratic country? It’s like the typhoid: nobody gave a damn when it was killing off prisoners. I mean, they were just a drain on the tax base anyways, right? It only became a problem when it trespassed into the free world. If you don’t have a Y-chromosome and live in a Red state, you’ve already lost a right. More losses are coming. This isn’t prophecy, it’s just human nature.

This subject has been much on my mind of late, as it became apparent to me that it was time to update my “Anatomy of a Wrongful Conviction” series. I first wrote about the case of Jeff Prible in 2014; you can read the original six parts of the series <here> if you care to. I wrote an <update> in 2017, and it is to this article that I would like to refer you. I’m aware that internet journalism doesn’t really work like this today. I know the public wants articles that only require five minutes of your time. I do not believe you can understand anything of importance in five minutes, and, if you are being honest with yourselves, neither do you. Jeff’s is a case involving massive levels of prosecutorial misconduct. It took a great deal of forethought to put together. In fact, in the words of Vic Wisner, the assistant DA who prosecuted Jeff, in order for his allegations to be true it would have involved “a conspiracy to frame this Defendant both in the free world and prison, so audacious it makes any frame up that had ever been conducted in the annals of crime look like child’s play.” He was speaking sarcastically at the time, obviously. As we shall see shortly, his tune is of a quite distinct musical genre today. What this means for you is that this situation is going to require some genuine time and analysis in order to understand. There’s no way around that. If you are someone troubled by issues in the criminal justice world — and I presume this fact, given you are reading this site — you simply have to know that five or ten or even fifteen minutes’ worth of effort isn’t going to get you much of anywhere. That sucks, but reality doesn’t care if you understand it, really. It will just keep rolling over you whether you comprehend it or not. So dig in. You don’t have to read <Day Seven> or even this piece in one sitting. Just bookmark it all and take it in sections. You can skip the initial paragraphs about game theory and begin with the one that starts with the phrase: “The basic facts are these…” Go on, skedaddle. Come back when you are up to date.

Done? Good. Let us proceed now that we are suitably informed.

In his petition for relief in federal court, Jeff asked for an evidentiary hearing in order to flesh out his claims regarding the network of snitches he believed Kelly Siegler had recruited to secure his conviction. The state, naturally, opposed this. You may recall from the earlier articles that Jeff had asked Keith Ellison, his federal district judge, for permission to suspend federal proceedings and return to state court for the same purpose. State courts, after all, are supposed to get the first shot at adjudicating state cases. Ellison accordingly ordered this and a hearing was held in Houston in June of 2011. During this two-day affair the court heard from Kurt Wentz, one of Jeff’s trial attorneys; Roland Moore, Jeff’s state habeas lawyer; and a pair of investigators used both by Jeff as well as by Hermilio Herrero, an inmate convicted by the exact same prosecutor using the exact same group of snitches held at the Beaumont, Texas federal prison facility. (For more details on this aspect of my reporting, see <Day Four>; scroll until you see the image of the outside day room: the following paragraphs detail the convoluted ways in which the Prible and Herrero cases are entwined.) During the state court hearing, evidence was presented by Wentz that had he and his co-counsel known about even a few of the myriad connections between Siegler and her informants, they could have easily torpedoed Michael Beckcom’s testimony at trial. Recall, the information regarding these links did not come out until years after Jeff’s trial, so at the time Jeff was his client, all Wentz had were a series of inchoate suspicions coming from the mouth of a man charged with killing five people. A number of years later, Jeff made some slightly more formal allegations about what he thought had happened in a pair of handwritten “writs” which he submitted to the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals, but this august body of juridical professionals ruled these to be inadmissible and tossed them out under Texas’s “abuse of the writs” doctrine. I put the term writs in scare quotes because Jeff’s product did not meet the standards set in Tex. Code of Crim. App. 11.071 regarding what actually constituted a writ in the first place. By violating their own standards on document classification, the court simply manufactured a means for disposing Jeff’s claims without the trouble of actually reviewing them on the merits — though, I note, they had no problem continuously referring to his allegations as “conspiracy theories” sans any investigation of their informational content. Nevertheless, after hearing all of this testimony and new evidence, the court claimed that “the factual basis for the instant claims were available when [Prible’s] initial habeas petition was filed in November, 2004” and that “a factual basis for [Prible’s] conspiracy theory may have been available at the time of his trial.” How, one might be forgiven for wondering, could the “factual basis” for Jeff’s claims have been available in 2004, when Jeff was only able a decade later to get his hands on portions of Kelly Siegler’s file which had been intentionally withheld? Remember, the reason Jeff didn’t know about Siegler’s extensive connections to Nathan Foreman and Michael Beckcom was because the state covered these links up. For instance, Siegler claimed at trial that she had only spoken with Beckcom once or twice on the phone, despite her knowing that the real number was an order of magnitude higher. She also hid three letters reputedly written by members of the snitch ring in a file labeled “work product” which shielded this from discovery by the defense; these letters were not handed over to Jeff’s team until 2011. As weird a conclusion as this was, the court then upped the ante by claiming that the information provided by Carl Walker — one of the members of the snitch ring who later changed his mind about participating in the scheme and who gave detailed testimony about how the entire plan was supposed to work (see <Day Five> for more on this: at the end of the article, you can read a transcript of Walker’s testimony and listen to an audio file of the recording) — was hearsay, even though his testimony was exactly of the same nature as the evidence presented at trial by Beckcom, which the court seemed to be completely comfortable with. The state court very simply punished Jeff for not having discovered the state’s corruption sooner, and denied him relief at the hearing.

Although the following is a rather obvious point, I feel compelled to state this as clearly as I can, just so you don’t miss it: nowhere in the state court’s response did they say that Jeff was lying. Nowhere did they seem to care about the information regarding the snitch network that had been discovered by Jeff’s federal counsel. The only thing they argued was that Jeff should have figured out that the state was lying sooner, and that his inability to do so meant he was now procedurally barred. Sorry, dude, off to the gurney with you. That’s what you get for not having figured out we were deceptive scumbags sooner.

This denial pushed proceedings back into the federal courts. Given the obvious absurdity of the state court’s arguments, in February of 2019 Judge Ellison ordered an exceedingly rare federal evidentiary hearing to be held, during which the court heard testimony from Nathan Foreman; Carl Walker; Terry Gaiser, another of Jeff’s trial attorneys; Vic Wisner, assistant DA to Kelly Siegler at trial, and he of the smartass-yet-embarrassingly-true comment featured earlier; and Kelly Siegler. In addition, the court reviewed depositions made by Michael Beckcom and a number of the prosecutor’s peripheral figures involved in Jeff’s trial. This three-day affair took place in April of 2019.

In my initial series, I was forced to speculate on a number of issues regarding how the various cogs in Siegler’s snitch machinery fit together. Nathan Foreman’s testimony bore out nearly all of my hypotheses. (To be fair, there were only a few ways this type of organized deception could have worked, and I simply asked the old cui bono question. The incentives for the liars were obvious and potent, and Occam’s Razor made filling in the blanks fairly easy.) Foreman testified that he was given information about the crime scene directly from another prisoner named Jesse Moreno, who in turn had received it from Siegler. He confirmed that a network of inmates was planning to use this information to obtain time reductions as a reward for testifying against Jeff, and that this circle intentionally utilized the phone of their prison’s unit manager to contact Siegler so that the Bureau of Prisons’ phone system would have no record of these conversations. This last is important because it again damages the state court’s conclusion that Jeff could have somehow detected the existence of Siegler’s deceptions: even if either the state district court at trial or the TCCA later on had allowed Jeff’s habeas attorneys to investigate his claims, they would not have uncovered the extent of the planning by obtaining the inmates’ phone records. Perhaps most importantly, Foreman categorically denied Beckcom’s claim that Jeff confessed to the murders while the three of them were on the rec yard together. He admitted that the snitches got Jeff drunk, but he testified that Jeff never talked about the crime, other than to say that “[the authorities] were trying to accuse him of something he didn’t do.” Foreman was pretty unequivocal about what a liar Michael Beckcom is: “[the man] should have been a book writer or something.”

Carl Walker testified next. He repeated to the court everything he asserted in his original statement: that he was recruited by members of the snitch network in order to get a time reduction; that these inmates already possessed a wealth of information unreported in the media about the crime scene before Jeff had even been transferred from the low security section of the prison to the medium, where the snitches were housed; that the group did indeed plot to have a photograph of Jeff taken with the rest of them for the sole purpose of bolstering the narrative that they were all a very tight group of confederates; and he repeated the story about the attempt to get Jeff drunk in the hopes that he would say something incriminating. Walker denied having written the letter which one of the members of the informants ring mailed to Siegler’s office, which stated that Jeff had admitted culpability. He stated that the only inmate involved in the plot that had access to a typewriter was Beckcom, a point I made in the original series. Like Foreman, Walker testified that Jeff never confessed to committing any crime. This was not, as the state court claimed, hearsay evidence: Walker was present during these events, he witnessed them. Please note the obvious falseness of the state’s arguments on this last point. The law and its forms of argumentation can often appear to be bewilderingly complex, to the point that we unwashed masses simply stop attempting to parse the rulings sent down from above because we can’t understand them. That is not the situation here. The court simply asserted a silly argument, knowing that Jeff’s Republican judge was going to support it. Siegler, after all, had been the Texas GOP’s standard bearer on criminal justice issues for years, so any tarnishing of her legacy dirtied them all. Jeff’s federal district judge –nominated for the bench by President Clinton and appointed for life — was not so minded. In an amusing footnote, Ellison slammed the state for not appearing to know the difference between hearsay, speculation, and directly witnessing an event, the judicial equivalent of slapping this other judge on the back of the head and calling him a dumbass.

Ellison then called Johnny Bonds to testify. Bonds was an investigator on the murder case working directly under Kelly Siegler. Despite this, at the hearing he asserted he never saw the three letters reputedly written by Carl Walker, Jesse Gonzalez, and Mark Martinez, which alleged Jeff had confessed to them. He admitted that it looked like a single person had written all three (another point I made almost a decade ago by analyzing the grammatical and spelling errors found in the letters). Interestingly, Bonds now admitted that within two minutes of meeting Nathan Foreman, his felt he was lying, that “he [didn’t ] know anything about this case.” He stated that he thought Siegler felt the same way. He could not explain, however, why the pair of them met with Foreman multiple times. He admitted that Foreman and Beckcom “might have colluded to get more information” out of them about the case and acknowledged that it did not seem likely that Jeff would have spoken to anyone he’d just met about the crime after he was indicted.

Michael Beckcom’s testimony was about what you’d expect. By this point, he’d been hounded by Jeff’s attorneys and investigators for years. He’d received his thirty pieces of silver multiple times, and was now a free man, despite having been sent to prison for a contract murder. He’d had plenty of time to analyze the shifting winds and regular revelations in this case and try to find a piece of stable ground where his story might be able to bend a bit without him being convicted for perjury. He now claimed, for instance, that he didn’t know how the conspiracy of informants came about, that “after [the] whole thing got set in motion, it kind of became evident to [him] that this whole group of, like, fricking ten guys were trying to get information, and somehow [he] ended up with the information.” What an amazingly fortuitous occurrence for him! I guess this is about the only thing he could say, since all of the other faux informants were now pointing their fingers at him as the ringleader: he was just lucky, y’all. He repeated the claim that Nathan Foreman was present when Jeff confessed; when confronted with Foreman’s testimony that he had never witnessed Jeff admit to any kind of wrongdoing, Beckcom insisted that his former cellie was now lying. One might wonder what Foreman would gain now for lying under oath, and then compare this to the reasons Beckcom might have for sticking to his story — and to the incentives they both had more than two decades ago when they concocted their scheme. For the first time, Beckcom admitted that Siegler had told him that his testimony would “probably get [him] out of prison.” That Siegler later stabbed him in the back and procured for him a reduction of a single calendar year off his sentence says everything about Kelly Siegler herself and what people get for trusting her, and nothing about why someone would go to so much trouble to craft the lie in the first place: the man truly thought his actions were going to result in the outside gate swinging open.

Vic Wisner took the stand next. At trial he managed a nearly perfect impression of being Kelly Siegler’s lapdog, but in federal court he seemed to be having some serious memory issues. He just couldn’t seem to recall much of anything about the case, alas. He now claimed, for instance, not to have any memory of the existence of Nathan Foreman, despite their star witness stating multiple times that Jeff had confessed both to him and Foreman. Perhaps Wisner can be forgiven for throwing Siegler to the sharks. I mean, it would have been a huge boost to his career to be her second back then, when everyone thought she was going to rise to the top of the office in a matter of years — and then who knew where? The Attorney General’s office was already being whispered about, maybe even the Governor’s mansion. It’s hardly his fault she ended up politically imploding the way she did. What interests me most about Wisner’s testimony was his belief that the real evidence against Jeff was not the snitch testimony but rather the presence of Jeff’s semen in Nilda Tirado’s mouth. That evidence, now entirely discredited, would make the testimony of the informants much more important. Wisner didn’t know at the time what Siegler did: her DNA expert was anything but an actual expert. Had Wisner understood how shaky the so-called scientific evidence was in the case, he might have better understood why Siegler put so much effort into Michael Beckcom and company.

Terry Gaiser, one of Jeff’s trial attorneys, confirmed at the hearing that Siegler had never told him about the existence of Nathan Foreman, Jesse Moreno, or any of the myriad other informants that she had been conferring with for months. She certainly never told him that she felt her snitches were liars or possibly attempting some kind of coordinated action against his client. Nothing about time reduction promises was handed over to the defense. Gaiser never saw the three letters from members of the ring which she had buried in her “work product” file; neither did he have any idea that Siegler had been communicating continuously with prisoners at the FCI Beaumont facility. Indeed, she specifically told Gaiser that she could not do so. Perhaps most importantly, Gaiser never knew that Siegler had been told by Pat McInnis, then head of the Harris County Crime Lab, that semen could survive in a person’s mouth for 72 hours. Jeff’s federal appellate counsel had produced expert testimony to this fact, but it wasn’t until 2017 — in yet another of the many instances where, gosh dangit, the Harris County District Attorney’s office discovered an additional file pertaining to withheld evidence in Jeff’s case — that this conversation between McInnis and Siegler came to light. This meant that Siegler knew scientifically that she was lying at trial when she told the jury that semen goes away “with a single swallow”, I.e., Jeff had to be present at the moment Tirado was killed, and Jeff’s story about a consensual relationship between Jeff and Tirado had to be a lie. Gaiser testified that had he been given these notes between Siegler and McInnis, Jeff never would have been convicted.

Of course, the star of the hearing was Siegler herself, and she didn’t disappoint. Despite using Foreman as a witness in a number of cases, Siegler claimed that she only met with him on one occasion. We know this to be untrue, as Bureau of Prisons records prove conclusively that she met with him in person twice, once in August of 2001 and again in December — never mind Foreman having been returned to the Harris County Jail on a mysterious federal detainer just in time for the grand jury to hear about Jeff’s case, and never mind the numerous phone conversations we know they had together. (I might have been able to write something interesting about this grand jury hearing, save for the fact that the transcripts were destroyed, which, I merely note in passing, is a violation of law which still has not been explained by the HCDA’s office). Siegler stated that they didn’t talk long in any case because she felt he was a liar “in a category all by himself.” This didn’t stop her from writing a letter to his federal prosecutor recommending a Rule 35 time reduction. In other words, two decades ago Siegler was perfectly happy to take Foreman at his word and was only now calling him a liar because he was in the process of blowing up her credibility. The hits continued: when asked about the letters supposedly written by Walker, Martinez, and Gonzales, she claimed that they were included in the file presented to Jeff’s attorneys at trial. This was an undeniable and particularly stupid falsehood: these letters only came to light due to a judicial order, an order handed down by the very same judge she was sitting in front of. She also stated baldly that Jeff’s was the only case in which she’d used prison inmates as snitches, despite public record being very clear that this was a frequent tactic of hers. Some of her deceptions were so silly they bordered on the imbecile: she claimed not to understand how Foreman had been moved out of Beaumont’s Secure Housing Unit on the same exact day Jeff was moved from the Low, even though we know the BOP performed this shift at her request; she went so far as to claim that she didn’t even know what the term “SHU” meant. This, despite the fact that she used the term herself during Jeff’s trial, which the record clearly shows.

In his ruling, Judge Ellison wrote that Siegler’s testimony was not credible on both major and minor points. He felt she “was also combative in demeanor and did not appear forthcoming with many of her answers.” His opinion of Michael Beckcom was similarly critical, that he was not a credible witness, and was “dishonest when it suited his needs.” To which the chorus happily sung: Duh.

Ellison’s ruling granting Jeff relief acknowledged the complexity of the case, the result of years of litigation which “resulted in a dense record full of complex arguments and detailed allegations, often branching out into different cases and implicating various incarcerated individuals.” Much of the ruling was spent shooting down the state’s contention that Jeff was procedurally defaulted from even bringing the evidence of Siegler’s duplicity forward — the Attorney General’s argument and an echo of the state court’s position. Frequent readers of this site may remember some of my previous essays dealing with the Antiterrorist and Effective Death Penalty Act (AEDPA, hereafter) and the constellation of cases this act birthed in support of its ultimate goal, which was to speed up the process of executions by severely limiting federal review of convictions. In particular, AEDPA “prevents defendants — and federal courts — from using federal habeas corpus review as a vehicle to second-guess the reasonable decisions of state courts” (Renico v Lett, 559 US 766, 779 [2010]). This concept of whether a ruling was reasonable or not is a much higher threshold for appellants to reach than merely proving the state court’s determination was wrong. This means, if you give it just a bit of thought, that the law is perfectly fine with judgments being flawed so long as some kind of process was adhered to. (This is not a recent phenomenon, by the by: Madison’s Bill of Rights emphasized consistency and fairness of procedure, while the French Declaration of the Rights of Man emphasized the consistency and fairness of outcomes. The former depends on evolving social situations, the latter is pegged to evolving moral codes. By cementing procedure in place, we ultimately guarantee that an outdated system continues long past the point where society considers it to be immoral. I submit to you that this is one of the main reasons it always feels like criminal jurisprudence is lagging by a few decades behind the moral standards of the rest of society.)

Although Jeff was arguing that the prosecution committed misconduct (specifically a violation of Brady v Maryland, which deals with the suppression of evidence which was favorable to the defense), he still had to overcome the challenge of being time barred. Should he manage to get around these bars, he would, in addition, need to reach the standard set in Maples v Thomas to obtain relief, which stated that the procedural default of claims can be lifted “if the prisoner can demonstrate cause for the [procedural] default [in state court] and actual prejudice as a result of the alleged violation of federal law.” Jeff’s first federal application for a writ of habeas corpus was filed on 18 June 2009; his fourth amended petition was submitted on 26 March 2018. AEDPA requires appellants to file everything within one calendar year of entering the federal process, so Jeff was clearly more than just a bit tardy, at least on that final filing. The question for the court came down to: was this his own fault, or did responsibility for this fall on the prosecution? Could Jeff (and by this, what they actually mean is: could Jeff’s attorneys) really have discovered the details of the snitch network earlier? Could he have debunked the flawed DNA testimony at trial without the communications between Siegler and McInnis?

Judge Ellison ruled that a number of Jeff’s claims were available for federal consideration due to Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 15(c), the “relation back of amendments” standard. This rule allows for amendments to bypass procedural time bars if the newly discovered facts “relate back” to information in the original petition. To do this, there must be a firm way in which new claims “are tied to a common core of operative facts” (Mayle v Felix, 545 US 644 [2005]. In other words, both Jeff’s original petition as well as his most recent amendments concerned suppression of exculpatory evidence by the same person (Siegler), involving the same period of time, as well as the same suspect matter, and were material for the same reason (for instance: Beckcom lying on the stand). What was different was the size and scope of the deception, not the type: apples which fell out of the tree after more recent, vigorous shakings were acceptable. Oranges, to continue the metaphor, would be barred, even if devastating to the state’s case. Thus, Ellison found that a number — but not all — of Jeff’s claims were not time barred, and therefore were open to review.

An additional issue was permitted by Ellison over the subject of Siegler suppressing the testimony of the head of the Harris County Crime Lab. This material was not turned over to Jeff’s attorneys until 11 May 2017. Section 2244(d)(1)(D) provides that the AEDPA limitations period begins to run from “the date on which the factual predicate of the claim or claims presented could have been discovered through the exercise of due diligence.” Judge Ellison rightly concluded contra the state court’s bullshit that this meant Jeff had one year from that 2017 date, not the date of his initial filing.

Now that the issue of the procedural default was out of the way, Ellison turned to those of cause and prejudice. Was there some sort of objective factor outside of the defendant’s control that impeded their efforts to comply with the normal rules of procedure in the state courts? Ellison found that it was “beyond serious dispute” that the state withheld reams of paperwork from Jeff’s attorneys. He pointed out the extensive series of lies proffered by Siegler, and noted that trial counsel did in fact ask for data on Siegler’s contacts with Michael Beckcom, the extent of which was never revealed. Similarly, it was clear from the record that this knowledge regarding the exact dimensions of the snitch ring was unavailable to Jeff’s trial lawyers. There was simply no way for anyone on his side to have known how the network was recruited or how it operated, and that this was because of the state’s suppression of evidence.

The state attempted to counter this argument by saying that Jeff could not establish cause for overcoming default because he “confuse[d] knowledge of the factual predicate of the claim with access to the best evidence supporting the claim,” to which I respond with: are you fucking kidding me? Who gives a crap? The state lied. All but one of the snitches has recanted. The DNA evidence was junk science. And the Attorney General’s office wants to split hairs about “the factual predicate” vs some hypothetical “best” evidence. Jeff may have suspected prosecutorial misconduct, but he had no direct evidence at the time, and in our system, you can’t go about willy-nilly making claims without anything at all to back them up. They’d have tossed his initial writ out of court if he had attempted this, evidenced by the fact that they did exactly that when he tried to file addenda to his first writ. In any case, Ellison thought this argument from the state was nearly as stupid as I do and decided that Jeff had met the standard for cause.

To show prejudice, the test is whether “there is a reasonable probability that, had the evidence been disclosed to the defense, the result of the proceedings would have been different” (Strickler v Greene, 527 US 263 [1999]). Let’s all pretend for a moment that this standard doesn’t require judges to look into some kind of crystal ball in order to determine what might have happened in some alternate timeline. Fortunately, in this case, it is patently obvious that the suppressed materials would have had a huge impact on the outcome of the trial, since it eliminated every piece of so-called evidence the state had offered to the jury. Indeed, there simply was no case once the DNA junk science was refuted and the machinery of the snitch network laid bare. It is difficult to see how any reasonable member of the jury would have voted to convict, even acknowledging Siegler’s skills a gifted rhetorician.

The end result of 88 pages of legalese was that Judge Ellison granted Jeff relief on six claims. He ordered the state of Texas to retry him within 180 days or release him from custody. We were all just stumbling into one of our first of many covid lockdowns when I heard the news about Jeff’s reversal. It was not even technically summer yet but the temperatures on my wing were already uterine. A gangly, basement-dwelling irritant a few cells down decided that we were all conspiring to kill him off with this “Chinese flu” and somehow decided that this necessitated trying to shoot us with blowgun darts on the rare occasions when we did get to go to the dayroom. Which of course meant I got a front-row seat for an application of Newton’s Third to the penal context: for every dumbass or hostile move there is an equal and opposite boneheaded reaction, which in this case meant a seemingly eternal roundelay of banal insults accompanying an aerial ballet of sharp projectiles. (It’s kind of horrible how hatred and violence can become so tedious, but that’s probably a subject matter for a whole other essay. Or maybe fertile territory for my therapist to explore. If I had one, I mean.) The JPay email telling me about Jeff’s reversal was the best thing had happened to me since early 2018. I remember standing at my door, paper in hand, arms raised in triumph. For the next several days, people assumed I was up to something, I smiled so much.

It wasn’t a complete win for Jeff: Ellison had denied him relief on several other claims, and I recall thinking that I hoped this did not come back to haunt him. My sense of why he denied some of these issues is that Ellison is keenly aware of being supervised by the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals, generally considered to be the most conservative appeals court in the nation. I have read several rulings in which he bemoaned his inability to follow his own reason or even the plain facts due to his oath to follow precedent set by that higher court. I believe he structured Jeff’s ruling in the way he felt would be the most palatable. The Brady violations were what really mattered, I reasoned. A reversal is a reversal.

I thought a lot about Jeff in the weeks after the ruling, both the person and the symbol he was becoming. He’d lost his father and his only son during the decades stolen from him by the state. His two daughters had lived most of their entire lives with a father seen only rarely behind a thick pane of glass. His sanity had frayed around the edges on occasion, but he’d hung on — just. It was an honor, I reflected, to have been in some ways a kind of publicist for him. I seldom find value in the things I have written, but in this one case I could at least claim to have gotten to the truth first. Even after I learned that the state had appealed Jeff’s reversal to the Fifth, I figured we had them beat, we’d won a very rare victory.

I settled in for another long wait.

Coming soon: Day 9, or The Revenge of the Fifth

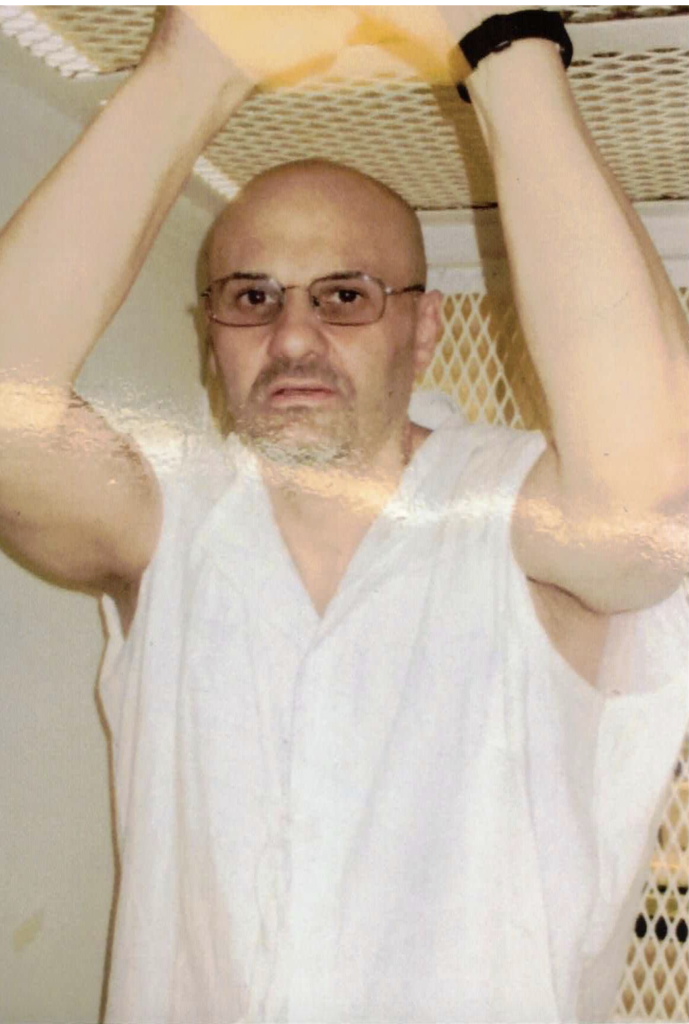

Ronald Jeffrey Prible

4 Comments

What Happened When a Star Prosecutor Was Accused of Running a Jailhouse Snitch Scheme - The Daily Dispatch

January 2, 2024 at 9:59 am[…] Jeff’s reversal,” Thomas Whitaker, the incarcerated writer who investigated Prible’s case, wrote. “I remember standing at my door, paper in hand, arms raised in […]

What Happened When a Star Prosecutor Was Accused of Running a Jailhouse Snitch Scheme – NewDYRTO

December 21, 2023 at 2:07 pm[…] Jeff’s reversal,” Thomas Whitaker, the incarcerated writer who investigated Prible’s case, wrote. “I remember standing at my door, paper in hand, arms raised in […]

What Happened When a Star Prosecutor Was Accused of Running a Jailhouse Snitch Scheme ⋆ RD Virtual

December 17, 2023 at 2:22 pm[…] reversal,” Thomas Whitaker, the incarcerated writer who investigated Prible’s case, wrote. “I remember standing at my door, paper in hand, arms raised in […]

When A Star Prosecutor Was Accused Of Running A Jailhouse Snitch Scheme - USA News

December 17, 2023 at 1:35 pm[…] Jeff’s reversal,” Thomas Whitaker, the incarcerated writer who investigated Prible’s case, wrote. “I remember standing at my door, paper in hand, arms raised in […]