Prison is an uneasy, shotgun marriage of routine and chaos. On one level, there is policy: thousands upon thousands of administrative directives, board policies, and security memoranda – an immense Rocky Mountains range of rules and protocols – regarded during certain moments as holy writ and about as mutable. Exactly like church doctrine, however, each individual officer has their own particular understanding or hermeneutics of the rules: a distinct set of beliefs about which chapters need to be given special attention and loyalty, and which can be safely ignored, especially when they are feeling indolent. In practice, this usually reduces to: How can I get my workload finished with the minimal amount of effort? In other words, stability and predictability are guaranteed unless convenience decides otherwise. But then, how do you, the prisoner, know when one of these moments has arrived? You don’t. And this means that words like “stability” and “predictability” get sucked into a semantic black hole and vanish from the universe of useful terminology.

Over the long run, prisoners are trained to equate the concept of rules with weapons deployed arbitrarily by people with power against those without. The lesson here is about as incompatible with the stated goals of the penal concept as is possible to conceive. Instead of refashioning the subjectivity of inmates to appreciate and respect rules, laws, and systems of self-government and self-control and the societies that create them, prisoners are taught only to seize the power themselves so they can do whatever they like. I’ve witnessed countless stabbings and assaults over the years, so I can report that quite a few of my fellow convicts have learned this lesson to a very high degree. Most of them – roughly 94 percent of them, in fact – will leave this prison world and return to your own at some point, so you, too, may get to witness just how deep that training goes. I hope not, but this is pretty basic, cause-and-effect stuff here, as close to inevitable as one can get when discussing predictions of future human behavior.

For we few inmates who have stumbled or clawed or lucked our ways into becoming better human beings in spite of the above, this makes every day a lesson in surfing the waves of unpredictability. You will never feel settled – never. You will always be imbalanced. You may have a basic outline for your day – to go to rec, to shower, to write a letter, to read a book – but a thousand factors beyond your control are going to impact the order in which one addresses this outline. Your life feels frayed, and it can be difficult to stay focused on one’s goals. There was a time when I thought this might have been a part of some sinister plan by the State, something to keep us all fumbling about instead of focusing on our cases. Experience has taught me otherwise, though: The TDCJ is congenitally incapable of this type of foresight, instead it’s just laziness and hostile indifference all the way down.

All of this is to say that, given the position of my cell, relative to the rest of the cells on Deathwatch, and the policy of how recreation was set up, I forecast that there was no way that I was going to be going to the dayroom before noon, on that, my first morning as a man with an execution date. I therefore settled into the rhythm of the typewriter, trying to find a way to soften the blow of the news to all of the people who had come into my life during my time behind bars. Even though I had been steeling myself for this eventuality for years, it’s hard to convey the reality of what was happening to people on the outside. For us in white uniforms, death is a constant presence, so one has to engage in some pretty elaborate self-deceptions if one is going to pretend to oneself that we too aren’t going to be killed. It’s easier for our friends and family to believe that some sort of miracle is going to happen that diverts us from the path that leads to the Styx. Having a date assigned is far more of a rude awakening for the people outside of the walls than it is for those of us inside them, the shock far greater. As hard as you try, there’s really no way to protect your people from what is at its heart a meticulously pre-planned murder. It just doesn’t fit in with any simile one can think of: It’s not like dying of cancer, not like a traffic accident or an overdose. It’s homicide, only in this case, your killers have told you years ahead of time what they intend to do with you. They cannot be negotiated with and, given the hard-conservative slant of this state’s judiciary, they can seldom be stopped. How do you address this with the people who love you? How do you apologize for the pain you are about to cause them, when the responsibility for this pain falls on an ideology, an agency, the State? I’ve never felt clumsier with my words than I did on that morning, and was relieved that I should have had all morning to try to come up with something that didn’t completely fall short of my goals. Naturally, prison being prison, the officers decided to surprise everyone by intentionally scheduling recreation ass-backwards, meaning I ended up being first. They showed up just a few minutes past 5:30am, telling me to get ready. I have become an alchemist of sighs.

The recreation schedule on the Row has shifted a bit over the years, generally with the arrival of a new assistant warden or major. There’s a sort of tradition that gets kicked off when this happens, where each new official figuratively (and literally and memorably on one occasion) struts about beating their chest and marking their new territory. To understand this behavior, it helps to think about the type of person who A) wants to work in a prison, and B) expresses this desire with such fervor and commitment that they move up the chain of command. I used to go out of my way in my writings to humanize the COs. This wasn’t dishonesty or artifice on my part: I needed to believe that the evil I witnessed was caused by something greater than individual human actors. This was a part of my defense against the prison, that I saw it as the site of a tragedy that twisted everyone who got sucked into its gravity well, inmate and guard alike.

I wasn’t completely wrong about this. The physical and ideological architecture of the prison really does warp us, one and all. I can no longer pretend, however, that the individual officers are victims in this process. To do so would be to absolve them of the choices they make every day to put on their uniforms, to ignore the pain and the unnecessary cruelty they witness and participate in daily. I will not negate their refusal to educate themselves on how other jurisdictions have constructed more humane prisons, systems that generate far more positive behavior and less recidivism in the offenders subjected to them than is found in Texas. The truth is actually very simple, though it took me a number of years to acknowledge it: Normal people would never consider working in a prison. I fought this knowledge because, in many ways, I identify more with many of the men in gray uniforms than I do with the men in white. I’ve had good conversations with some of them, laughed with them, fed them tacos and pies when the cameras were down, when all of us could get along a little better because the administrators weren’t looking. I made excuses for their behavior, for their continued employment, especially during the depths of the Great Recession. Man, I told myself, these are just people who need a paycheck. Then I watched as some of these people slowly changed, the way their eyes would light up when they watched the Extraction Team beat someone up – the way they would sometimes join that very team. I read the statistics on hiring and realized that recession or no, the TDCJ has dealt with the same staffing problems for two decades. (For instance, of the roughly 26,000 guards working in the system statewide, a whopping 28% left their jobs in 2017. Approximately 15% of all staff positions remain permanently unfilled, and this wasn’t markedly different in 2009.) During the prison construction boom of the 1990s, conservative politicians built facilities in rural counties, in an effort to boost these economies and reward them for the GOP takeover of state government. Decades later, this tactic has clearly backfired: Most of the decent, hardworking citizens in these small towns have quit, seeing firsthand what the prison environment was actually like. The people who remain are those who are politically, ideologically, and religiously in-line with the ritual degradation of lawbreakers – essentially the last subset of the population that you would want to give arbitrary and total power over other human beings to if rehabilitation was the goal. There simply became a point where I could no longer resist the truth: Anyone who would want to work in this place has something deeply broken about them. That may sound like a controversial statement, but you’d be surprised at just how many of the officers here admit to this. Sometimes they even laugh about it: “Aww, shucks, you got me. We’re all fuckin’ crazy.”

All Death Row staff members are volunteers. They are asked about their feelings on the death penalty at the Academy, meaning every single one of these people I attempted to humanize chose on at least one occasion to completely dehumanize me for a paycheck – and a lousy paycheck at that, less money than is the average hourly rate for workers in the Greater Houston Metropolitan Area. This further reduces the likelihood of a normal, decent, politically-neutral individual remaining employed in Polunsky’s 12-Building for long. One encounters such people, briefly. We convicts look at each other and just shake our heads, knowing that they are not going to last. They never do. We hate to see them leave, trust me: Contact with the truly human is like a cup of clean, cool water to someone crossing the Atacama on foot. But I don’t blame them for decamping. On the contrary, I salute them. They are taking a stand. It’s not the type of stand I’d prefer – I’d love for someone to pull a Shane Bauer on the State and leave this place with videos and audio recordings, so that some of the things I write about could be conclusively proven. But at least it is something when I hear about such a guard quitting, sometimes in the middle of a shift. This always fills me with a tiny burst of hope for our species. And it’s a better conclusion than it could be: Years ago, Officer Woods walked to his car, took off his uniform, and shot himself in the head. No one knows why he committed suicide, officially. Unofficially, he’d just seen too much. He was one of the good ones, and prison is designed to kill the good.

*****

Of those who remain on the job, there are those capable of swallowing their doubts, morals, and decency, and then there are the truly gung-ho types, the ones who love to work in prison. Of this latter group – sometimes referred to humorously or pejoratively as “Robo-Cops” – there is a small percentage of guards (usually, but not always, men) who have the managerial experience or education to become ranking officers. Such officers generally spend more time riding a desk than controlling a wing. When they do show up, they are immediately denigrated by the inmates. I’m not saying this is a wise position for prisoners to take, because it’s not. I can’t tell you how many times I had been having a cordial, substantive conversation with a ranking officer about a problem that might have gotten resolved when some idiot started cussing the officer out or throwing things at them. We inmates are our own worst enemies most of the time. Even acknowledging this, if a sergeant or lieutenant is walking the pod, it means there’s a problem, a problem that is almost certainly not going to be resolved in favor of the inmate. So now the prisoner is mad, and rank is mad for getting cussed out. This breeds bi-directional contempt. By the time an officer reaches the pinnacles of Mt. Goon and puts on their major’s insignia, they’ve been swimming in a virtual ocean of anger, rage, and despair for decades. They will detest inmates and see us as a sort of monolithic entity: The lowest common denominator, all the time. They will have no interest in our positive qualities, our good works or behavior. They’re just going to want to establish who is boss. When a new major shows up, everyone – inmates and COs alike – brace themselves for a storm. This is basically a law of prison.

For some reason the recreation schedule is almost always one of the first victims of this REMF’s something-must-be-donery genes kicking into overdrive. All sorts of “new ideas” get floated, filled with the helium of the new major’s arrogance. Quietly, gradually, the officers wrangle matters back into some remnant of the prior format. Years of lazy optimization have already proven the quickest way to finish recs and showers. For Level One offenders (the classification grade for the best behaved), recreation is offered five days per week. On three of these days, inmates are placed in the dayrooms, which are located mere meters from the front of the cells. On the other two days, we are given access to the outside rec yards.

On even numbered days, officers are supposed to begin setting up the schedule for Two-Row; on odd numbered days, for One-Row. This is meant to give inmates an idea of the time of day they will be going, and to increase the likelihood that everyone will get at least a little bit of sun once per week. Sometimes the officers will get sneaky and start on the alternate row, hoping to catch a bunch of people unprepared and asleep. When this happens, many inmates will refuse rec, decreasing the COs’ workload. Even when this doesn’t happen and the inmate says he wants to recreate, an officer will write on the paperwork that the offender refused; if the man is only half-awake it’s harder for him to argue his point later. (Not that it would do any good: If the rec sheet says you refused, you aren’t going to rec, period, full stop). This is exactly what happened on my first day on Deathwatch: I was the only person in the section who was up at 5:25am, so I was the only person who got to go to the dayroom that day.

On all occasions we recreate alone. It is simply a fact that in Texas, death-sentenced humans are never allowed to touch anyone. Barring a massive misfiring of the engines of justice, each one of us touched our last living creature the day we were arrested. The last time I touched another person’s skin was in 2007, during my last few weeks in the county jail. I was playing chess in the dayroom when a mini-riot broke out over the television schedule. I was one of two Caucasians in the entire tank, so I became an instantaneous target. That’s my last memory of touch: Me, parrying blows and trying to put a wall to my back. That sensation is so careworn and yellow from age and my repeated attempts to take it out for analysis that it feels almost mythical to me, like something someone else related to me from their own life.

Recreation is important to most prisoners. It’s one of the few choices we inmates have, one of our few privileges. I haven’t always agreed with this view. The dayroom is a horribly boring space: a small cage with a chin-up bar and a toilet, essentially. This sounds suspiciously New Agey, but I found over the years that my mental and physical discipline were inextricably linked; there was no point in trying to wrangle my mind into order if I didn’t work my body out, too. Indolence in one quarter crept stealthily into others. That doesn’t mean I love certain exercises. I have a nine-millimeter hollow-point bullet in my left arm, the scattered debris of which looks like a plane wreck in an X-ray image. I do my push-ups and chin-ups, but I don’t much like them. What I truly love to do is run. There’s no space in the dayroom for anything but tight little circles, but still: Running has become an almost meditative activity to me. I hesitate to call it spiritual, but it might be as close to that word as I’m likely to get.

Given this, and given that some officers are going to actively try to cheat prisoners out of recs and showers, I came to the conclusion pretty quickly that it paid to be a morning person. Convincing my circadian rhythm of this was an entirely different matter.

For most of my nearly 4,000 days on the Row I stayed up at night and slept during the afternoons. The main advantage of this schedule is that it is relatively quiet at night. Depending upon the section one is living in, the volume during the day tends to range between a spirited cocktail party and what I presume a large thermonuclear warhead detonating adjacent to my eardrum would sound like (minus the relief of having my component atoms redistributed over half of Texas, obviously). Start off with a layer of basic, casual conversations between neighbors. These must be maintained at a much higher volume than the distances would suggest because you are having to project your voice forward so that it bounces off the concrete walls and reflects back toward your intended target. Considering all of the odd angles, it can be very confusing (and frustrating) during one’s first few months when one is trying to figure out why it is easier to hear someone downstairs talking than one’s own neighbor. Even if everyone were just talking, it would be loud. Because of this, and because prison stopped being a place where “respecting your neighbors” was a part of a valid code about the time the Prisoners’ Rights Movement was sputtering to a close under Rehnquist’s careful administration of the SCOTUS, people end up shouting over each other instead of waiting for their turn. Now sprinkle in the arguments. What’s there to argue about in ad-seg? Everything. Anything. Things you wouldn’t believe anyone on the planet could care enough about to shout over. These are inevitable when you subject human beings to the sorts of existential and environmental pressures common in a modern dungeon. Add a hefty dose of people trying to shout chess moves to each other; even with the most meticulous coding system imaginable, the aural landscape is so congested that mistakes are unavoidable, which in turn propels new arguments. Over all of this can be heard homemade speakers playing. These will get progressively louder as the owners try to drown out the noise coming from the rest of the section, a feedback loop that slowly ratchets up the frustration level of everyone.

All of this takes place under normal operating conditions. If the system ever messes someone over, multiply the above by the sound of inmates kicking their metal doors, over and over, sometimes in spurts for hours, a vibration that can be felt through the metal of your bunk, sink, and desk. I read once, a few years back, about the tiny temblors seismologists had begun to pick up in the Livingston area due to fracking wells. Sometimes I wonder if they were really just picking us up on their monitors. It really is bad enough to make one wonder if the gear that connects the wheel of your brain to the engine of empirical, objective reality is starting to slip.

This is more than idle speculation. Death Row – indeed, all super-seg facilities – are littered with men who have become unmoored from the world occupied by everyone else. Most of these poor souls were already sick when they came to prison, their psychoses injected with steroids by the conditions. These are bad enough, but perhaps even more tragic are the so-called “Section Eighters” (the State’s term, not mine) who arrived here sane and slowly lost their minds. It takes far less time to forget who you are than most people would want to credit. You can hear these men talking to themselves when you live next door to them. It’s impossible to avoid their IED-esque explosions of manic laughter or delusion-filled shrieks. I once heard Jonathan Green – a 400-pound hulking monster of a man – nearly tear his metal desk off the wall while trying to battle a “demon”. So terrified was he that he would run the few steps from his door to his back wall at full speed, slamming into each every few seconds. Despite an obvious case of full-blown schizophrenia that even the State acknowledged, Jon was reduced to a zero in June of 2012. Four months later, on the 10th of October, he was killed. He was the one hundredth man executed in my time on the Row. It’s hard to forget a thing like that.

You don’t completely evade the above when you live on the night shift, but generally it’s quiet enough to think, or what passes for such in this head. Other advantages include: the reception of additional radio stations, especially if one can fabricate an antenna from the spools of wire found inside any basic transformer; the temperatures are far more comfortable, at least during the scorching summer months; and, one tends to find oneself involved in far less drama, simply due to a reduced exposure to other inmates. This last is no small matter. Take any group, it doesn’t matter who: Accountants, judges, ministers, whoever. Toss them all into cages, then jam these together so that fourteen of them are compressed into the square footage of a small living room. Add massive levels of inequality: Inmate A manages to snag an excellent attorney, while Inmate B is handed off to a lawyer with twenty other clients and a commitment level that rarely rises above that of a disgruntled clerk at the DMV. Give some of the prisoners money and supporters; deny this to others. Allow some to have coffee and warm clothes for the winter and decent food and books and magazines; leave others in their cells with virtually nothing to do but stare at empty concrete walls. Then tell these people that they are all going to be tied down on a gurney and subjected to a deliberate overdose, but that some will reach this point in a few years, while others will get to live for decades. I don’t care how supposedly morally upright the people are who you are subjecting to such treatment, desperation and envy and boredom will crawl into bed together and will give birth to drama and conflict. The best way to avoid this, sadly, is simply to make oneself as invisible as possible. So, sleeping through the hours when most people are at peak activity helps more than you’d think.

The downsides of a life lived at night are considerable, however. Most of the units in the TDCJ operate on two shifts: the aptly named “Day Shift” begins at 6:00am; and the “Night Shift” commences at 6:00pm. Death Row operates on a 5:30am to 5:30pm schedule. I’ve never been able to get a clear (or rational) answer for the 30-minute difference. In any case, this means that events tend to start happening around the 5:30am mark: The rec sheet is compiled, and then the first round is escorted into place around 6:00am. Cue the dayroom racket. The morning delivery of medications arrives soon thereafter, usually followed by the Necessities Crew, who hand out towels, socks, and boxers (on Mondays, Wednesdays and Friday), sheets (on Tuesdays), and one roll of toilet paper and razor (on Thursdays). Visits begin at 8:00am on the Row during the week. So, there’s really no point even attempting to sleep until after lunch is delivered sometime after 9:30am. On perfect days (i.e., when everything happens exactly as dictated by protocol), one might be able to snatch around six hours of rest between lunch and dinner, provided that one has jammed a pair of earplugs in so deep that they are on intimate terms with one’s gray matter. Since “perfect” is an almost mythological concept in prison, this pretty much never happens. The relative quiet of the night hours is precious, but you often pay the hefty cost of living life in a constant state of exhaustion.

I finally settled into a sort of compromise schedule in 2014. I would start my day around breakfast, sometime between 2:30am and 3:30am. Don’t ask me why they serve chow at this ghastly hour, because I’ve never been able to get a straight answer beyond that this is how “things’ve always got done”. The best I’ve been able to come up with is that way back in the 19th Century, when Texas was constructing its first prisons, almost all inmates worked either in the fields or for the convict lease system. Presumably, this required everyone to be up and ready for work at daybreak. Very few prisons even have operating fields anymore, having discovered that Big Business can provide for their needs at cheaper rates (not to mention some rather nice campaign contributions in Austin). I don’t know why the chow schedule has survived for this long. In the South, devotion to tradition is almost always considered to be morally virtuous, even when said devotion is mindless and the tradition lacks any rational justification. Some would say such fealty is especially virtuous the less sense it makes…

The few hours between breakfast and the start of recreation were usually the best part of my day. Almost every word I’ve written over the past four years was composed in this brief window, a cup of instant coffee on my table, NPR playing softly in the background. For just a little while, it was possible to pretend that the pursuit of things of the mind really mattered, that if I immersed myself in the attempt to think worthy thoughts and to conquer complex subjects, I would in some way find a form of redemption. It’s a nice illusion, daily smashed into a thousand jagged shards, but I keep coming back to it. I don’t always know why. Mostly, I just don’t know how else to survive here.

When the screws banged on my door to tell me to strip naked if I wanted to go to rec, my first thought was to deny, to “VR” (verbally refuse) in the vernacular. Inmates on Deathwatch always recreate in A-Section’s dayroom: This is the only place we are allowed to go, and no other sections are allowed to recreate there. We Zeroes are, in a very real sense, quarantined from the rest of the condemned. There are obvious practical reasons for this separation, though they have nothing to do with the one that probably came to your mind first: That men with dates are desperate and therefore dangerous. In my eleven years on the Row, I can think of only two physical altercations initiated by inmates in the months leading up to their deaths. The first was that of Ray “Ray Ray” Jasper, who fought the Extraction Team on the morning of his date, the 19th of March 2014. The word is, he really gave them hell, to the extent that members of the team spoke about him fondly as “a real man” for months afterward. The second is somewhat more apocryphal, in that no prisoner was a witness, only officers: On the morning of Rogelio “Cowboy Roy” Cannady’s date on the 19thof May 2010, he is said to have slammed seven bottles of prison hooch before his final visit. Prison wine is about as foul a liquid as it is possible for a human being to ingest. So, by the time his visit was over with, he was so obliterated that they had to carry him to the death van to transport him to the Walls Unit. I can’t say I blame him for this. That I’m including this as an example of a “physical altercation” is to highlight my point: Whatever else the condemned are feeling in their last months of life, violence simply isn’t a part of it. If you read much of the current literature on prisons, you won’t have to travel very far until you run into the bog Foucault dumped onto the field. According to him, the “docility” I described in the soon-to-be-departed is the result of a Beccarian concept of discipline consisting of hierarchical observation, classification, a regimented timetable, and a regime of non-idleness. My sense is that the decency displayed by my peers has far more to do with their innate character and the maturity they have developed during their time on the Row than with some sort of “synoptic regime of capillary power”. If anything, I’ve noticed that the stronger the panoptic pressure, the stronger the resistance this power produces. Only intrinsic goodness operates against this pressure, a point that I hope gives at least a few of you pause.

So, no violence. In reality, the reason that the system needs to separate those with dates from those without is that the Zeroes dramatically and rudely pop the hope balloon. Hope is the fuel that powers the maturation process engaged in by many of the condemned: Hope for salvation (usually religious in nature, but not always), hope for release, hope for redemption. Take this away, and men do start to become violent. (Again: this applies to any set of human beings, not just felons.) The system knows this, so they keep those of us apart who have reached the point where our reserves of hope are pretty much used up. In particular, men without hope tend to become violent toward themselves. There’s nothing the administration at Polunsky hates more than a suicide on Death Row. It offends them that anyone would have the gall to mock their concept of justice by depriving them of the pageantry of an execution. I know this is hard to believe. You are strangers to this world. It shocked me the first time a suicide took place in my section and the warden stormed in, screaming, seething. I initially thought he was merely incensed over the fact that the shift officers hadn’t been doing regular security checks. I actually thought for a moment that he was angry because a man who might have been helped was now dead. But then I heard him shouting about how the “fucker” had “gotten away” from them. I recall standing at my door, mouth hanging open, just totally incapable of making sense of the scene. This man, this warden, is still in the system, as the Division Deputy of an entire region of prisons no less. The only time I ever saw him happy was the morning in April of 2008, when the SCOTUS allowed executions to resume after ruling in Baze v Rees that lethal injection was constitutional. I was coming back from visitation, so I hadn’t heard the news yet. The warden was walking down the hall toward us, whistling. The escort guards turned to look at me and we all had pretty much the same thought in our minds: That somebody was about to be in a whole heap of trouble. Turned out, that somebody was all of us – Texas butchered eighteen men in the subsequent seven months.

*****

My reluctance about going to the A-Section dayroom on that first morning had everything to do with this quarantine, with who I was being sequestered with. During my eleven years on the Row, I was friends with many of the 161 men who had passed through Deathwatch on their way to the medicalized gibbet. Whenever I had the opportunity, I’d ask them about their experiences in as much detail as they could handle at the moment. I figured I might be able to inoculate some of the anxiety I was potentially going to feel when my turn came if I attempted to experience those last days with my friends, a sort of trial run for my own ending. It was an experiment in deep empathy, in consistently staying with my friends during their last hours, even if only in an imaginary sense. This was something that I’d once been good at as a child but had, admittedly, cut out of my personality in later years. Almost to a man, these cons reported that the most important variable in the Deathwatch equation was who was living in the cells around them. If everyone took their ends “like men”, there was genuine solidarity, kindness – celebration, even. If people were freaking out, this stress and drama could seep down the run like an oil spill, like a malignant growth. I’ve known men who’d had their beliefs in mankind rekindled within their last days thanks to the companionship found on Deathwatch. I’ve heard about some pretty epic parties over there, a fairly remarkable thing when you stop to think about it. I’ve also known men who were practically skipping with joy on their last mornings, so ready were they to be rid of their neighbors.

Which was to be my fate was something I’d begun thinking about even as I was being escorted to the section from the major’s office the previous day. The almost total silence that had enveloped the section since my arrival was a bad sign, one indicating that people were not getting along. My neighbor on the right, Juan, apparently only wanted to talk via the little crack that existed in the back wall of our cells, rather than in the open over the run. I more or less had an idea of what the problem might be, but some reconnaissance was going to be necessary to confirm it. That’s what it felt like on that first morning: Like I was stepping across enemy lines.

No one was awake for the first hour or so of my time in the dayroom. I received a few kites (written or typed messages) from friends of mine on A-Pod, commiserating with me over my date. Technically, passing kites from one dayroom (or cell) to the next is a violation of the rules called “Trafficking and Trading”. In reality, the officers rarely bother to stop this, largely because this is one of our red lines. The administration knows very well that if they attempted to halt this, there’d be a revolt. Shortly before 7:00am, William Rayford flicked his light on in 7-Cage. I could hear the pipes chundering in the walls as he completed his toilet. A few minutes later I saw his lean form shuffle up to the door, pushing his walker, plastic coffee mug in one hand. The expression on his face ran through a quick kaleidoscope of emotions upon seeing me: incomprehension flowing quickly through surprise-joy before settling on anger-pity, with maybe a tiny echo of guilt over having been happy to see me before the rest of his brain conveyed to him the full meaning of my presence in the section.

“Oh no, Mr. Thomas,” he groaned. “Not you too now. When did you sneak in?”

“Afraid so, Mr. Rayford. I received my ticket yesterday,” I replied. “I didn’t feel as if I was getting the complete death sentence experience without a trip over here.”

He smiled at me, his teeth bright little jewels. “You didn’t have to come down here to collect yo’ debt. I coulda sunt it to you.”

“Rayford, I’ve been waiting on that cheesecake for two years,” I laughed, before glancing down the run. “You the only man on One-Row?” After he nodded, I got as close to the bars as I could and lowered my voice. “The hell is going on over here? It’s like a ghost town. Is what I’ve been hearing true?”

Rayford was one of the genuinely good souls on the Row, and he initially didn’t want to tell me anything, the answer being so awful. Out of the 230 or so men sentenced to death in Texas, he was one of maybe fifteen guys who were universally loved by members of every clique, group, and gang. In his mid-60s, he was far too old for the nonsense and games we convicts run at each other. If he had a flaw, it was that he enjoyed a cocktail or six from time to time. His decency was on full display when he was in his cups, when he would spend hours cooking tacos and pies for his neighbors and making absurd bets on his beloved Dallas Cowboys. All told, he racked up a little over 1.4 million dollars in fake bets with me over the years. We’d settled out of court in 2015 for a piece of his cheesecake, though the Fates had conspired to keep us on separate pods since. He always called me “Mr. Thomas”, which made me feel very uneasy at first. I didn’t delve too deep into his past – a big no-no in the institutional universe – but I hated the thought that this was how he’d been trained to address white folk over the course of his years. He reminded me of Roy Blue, the man who shined shoes in the men’s locker room at my grandfather’s country club when I was a boy. Rayford’s mannerisms and speech were so perfectly appropriate for a civil rights documentary, it was like someone ordered the man from Central Casting. “You know you don’t have to call me mister, Old School,” I’d told him soon after we’d met. “I’m not that America. I’d have voted for Obama.” He considered this for a long moment.

“I figure civility don’t cost me nothing.” He was right. So right that I had ended up stealing this line and the philosophy behind it for future use.

I could see Rayford weighing his words on that first morning, loyalty to me at war with his desire to be fair to everyone else. “All I’m gonna say, Mr. Thomas,” he answered finally, “is you best mind yo’ tongue. He been meetin’ with the poh-leece real regular like.”

The “he” in question was Anthony “T-Bone” Shore, a man who Texas had tried to execute the month before on 18 October. In the weeks leading up to his date, local media began reporting that Shore had some information or evidence in his possession regarding the death of Melissa Trotter, the victim in Larry Swearingen’s case. These reports were in many ways contradictory, but contained a single common thread: Shore apparently had turned over a map of the crime scene containing unreported, “polygraph key” details written in Larry’s handwriting. As Larry had always maintained that he was innocent of Trotter’s death, this was dynamite news, although no one knew exactly what the truth was. Some maintained that Shore had tricked Larry into providing the map, at first claiming he was going to take the blame for the crime only to then turn it over to the police in an effort to stay his own execution. A more macabre version of this story held that T-Bone was trying to rack up one last body on his tally before he was himself killed, a last statement of his true character. Others believed that Larry had, for some years, come to believe that T-Bone was Trotter’s true killer, and had drawn the map in an attempt to get Shore to remember the scene. The entire building was redolent with reports that Shore had been seen meeting with obvious law enforcement types, men who proudly sported badges and serious, official looking IDs hanging from their necks on chains. I didn’t know what to think, except that the police were talking to him about something, and a man willing to throw another inmate under the bus once wouldn’t hesitate to do so again – even if the story he was telling was completely fabricated, or built up out of facts from unsolved homicides that he had himself committed. Such a story wouldn’t be sufficient to get one of us charged with a cold case murder, but it would certainly be enough to have cops swarming into one’s life and to have the media reporting on the allegations, none of which would contribute to a peaceful final few months. In any case, whatever he was up to, it had already managed to postpone his execution date by three months, so the least one could say was that it was effective. No wonder the section was so quiet.

I’d known T-Bone for years, and had always managed to have cordial interactions with him. You get to know the men living in your section to a degree that sometimes confuses people in the freeworld. How can one become friends with others in a solitary confinement wing? Aren’t we too isolated for meaningful contact? The truth is that ad-seg comes in a bewildering variety of shapes, restrictions, and durations. During my first six months in the county jail après-arrest, I was kept in 2sep10. This was true solitary confinement in its most draconian form: solid steel door, tiny viewing window that remained sealed except for during counts, no windows or television or radio, an oasis of boredom in a desert of horror, to reverse Baudelaire’s formulation. Even when the little window on the door was left open on rare occasions, the only view was that of a white painted cinderblock wall. There were five cells in this hallway. The screws kept the air-conditioning on full blast all winter, to the extent that you couldn’t really use the vents to communicate with your neighbor – you simply couldn’t make out many of the words they were shouting over the roar of the air. On one occasion, when the University of Texas won the National Championship game in 2005, I could hear dozens of men from the general population tank erupt into raucous cheers, but I had no idea there was even a game – I had completely lost track of the date. I thought maybe a riot was taking place. I only learned the truth later that morning when the officer delivering breakfast mentioned the victory. By the time officials eventually let me out into the general population, I was a tightwire humming with a high-voltage mixture of confusion, anger, paranoia, and anxiety. The administration had to have known this, but they weren’t in the mood to do me any favors: Instead of placing me in a tank filled with people with similar disciplinary histories, they stuck me in the Max Tank, a high-security environment for the most violently incorrigible inmates.

The guards escorting me to my new home kept casually talking about how they were glad they didn’t have to live in 2E, how they hoped I knew how to “protect [my] ass”. I don’t recall the exact wording of their taunts, only the character, so keyed-up on adrenaline and fear was I. I’m not proud of my behavior in that place. There was violence every day in that tank, and I did what I had to do in order to ensure everyone else got the message that I was not to be bothered. That defense feels morally suspect to me but, given the options, it was all I could think to do. Only in prison can a man be condemned for having “violent tendencies” when all he was doing was keeping himself from being raped.

I was reduced to an even sorrier state after less than a week in a “midnight cell” at Limestone Correctional. There was only one of these cells in the entire facility, and I had been “temporarily” shunted into it due to a lack of housing in a regular wing. Nobody apparently informed the turnkey boss that my placement in seg had nothing to do with a disciplinary violation, because he gave me the “full treatment” (again: their words, not mine). The space inside this cell was just large enough for a bunk to be carved into the concrete wall and for a pipe that conveyed cold water. The door was sealed and the lights were turned off, ushering in the sort of darkness that deep caverns might envy. (Years later, when I read about Jack Henry Abbott’s similar experiences in one of these cells – the way he started pressing on his eyes in order to see explosions of colors, the myriad insects that would crawl over his sheetless body, the cold that seeped out of the walls and took up residence in his bones – I had to put the book down, I was shaking so bad.) It wasn’t until my seventh morning in the midnight cell that someone in the administration realized that an error had been made, and a sergeant ran down the hallway to let me out. That’s what he claimed, at any rate, that he literallyran. He apparently had time to stop off at the SORT team’s offices, though, because six armor-encased soldiers were standing behind him as he kept repeating how sorry they were. Over and over again: “Whitaker, we’re sorry, man, we’re sorry. Be cool.” I couldn’t even look at them when they opened the door, the light was so bright. I put on a nasty scowl because I was afraid. The truth was, if one of them had tried to hug me, I’d have allowed it, I’d have wept and clung to them like someone pulled from a sinking ship. That’s how messed up I was, I’d have actually let one of these people be kind to me. Crazy.

Experience is a language and I realize that few of you are really going to be able to understand much of the above. I don’t know why I feel compelled to write sometimes in the second person, as if I were directly addressing some kind of reader. I still believe in the idea of writing for posterity, that some future generation is going to be more progressive, more mature, and that these words will in some way remind them of how ghastly humans could still be to each other in this supposedly modern era. I feel compelled to remind them that their identity, the morals they adhere to, the positions they claim to believe in: These things are far more temporary than they realize. The self and all of the concepts that valence it can be obliterated by a cell. To those of you who cling to the libertarian end of the free will versus determinism debate, feel fortunate that you have never experienced a midnight cell. Give me seven days and a cadre of malicious guards, and I will break you of your delusion that context has no genuine impact on one’s moral compass. Seven days, and I will convert you into someone capable of the most astonishing violence. I know some of you will refuse to believe this; you think this tangent is some sort of rhetorical trick on my part to engender sympathy. Cherish your ignorance, O unknown and unknowable reader of posterity: Cherish your fucking ignorance.

Solitary on Death Row is nowhere nearly as restrictive as the cells listed above. Officials in the TDCJ are well aware that if the condemned were placed into total isolation nobody would be sane by the time a death warrant was issued. Talking is possible, even with the ear-shattering levels of noise one experiences on a normal day, because the doors have two narrow sections cut out of them that are covered with metal wire. Some of the other senses aren’t completely left out, either. There are walls separating you from everyone else, but you can still smell your neighbors – especially those who rarely shower. It takes a team of three officers (two rovers and one in the picket) to escort offenders on the Row to the shower, so the system certainly isn’t going to insist on such fastidious concerns as daily (or weekly, or monthly) bathing. I’ve had neighbors who announced their return from rec or visitation via the olfactory organ long before I caught sight of them. (There are no nose plugs, alas. Though, after living around inmates who are so insane that they spend their afternoon hours smearing feces on their walls, auto-asphyxiation does begin to recommend itself powerfully.)

So, despite the physical barriers imposed by placement in an ad-seg wing, one can still get to know one’s neighbors quite well; there are certainly those from amongst my peers who would opine that you can get to know everyone a little too well. Whatever one inmate may tell their friends and family in letters or the visitation room, whatever one’s lawyers write about one’s mental state in appellate briefs and writs, a man’s true character is largely known to the other prisoners forced to live within their orbit. We know who the con-men are, the liars, the charlatans, the genuine killers, and those who are selling wolf tickets in an attempt to remain safe. This last category is no small matter. American society – not to mention the courts – have taken a largely hands-off approach to prison administration over the past five decades. People get hurt here, they get extorted, beaten, raped, killed. In these halls, respect is spelled: F-E-A-R. Given this, I can sort of understand why men like T-Bone behave as they do.

Anthony came to the TDCJ in November 2004, accused and convicted of the serial rapes and murders of a number of young women. There was a time in relatively recent memory when such a case would have immediately and aggressively sealed his fate, even in an ad-seg wing. The penal codes that once demanded the subjugation of rapists – especially pedophiles – have in many ways been revoked. The current paradigm is best encapsulated in the oft-heard phrase “getting down for yourself”. This essentially means that one needs to focus only on one’s own needs and goals, and to ignore or even mock collective action: Think Ayn Rand, only with shanks. This shift is a favorite topic of conversation amongst older cons. I’ve heard the blame for it laid on the shoulders of everything from video games to the Illuminati. My sense is that this was a consequence of both the death of the grand ideologies that postmodernism started strangling in the 1970s and the worsening of prison conditions ushered in by the Rehnquist Court’s jurisprudence on the Eighth Amendment. As prisons were required to offer less and less (as claimed by the conservative majority in Rhodes v Chapman: “deprivations… simply are not punishments”), the plight of prisoners worsened to the point where a predominately economics-minded ethos took hold. Instead of the primary antagonism being located between the guards and the prisoners, it shifted to one of convict versus convict over increasingly scarce resources. In this atmosphere, the idea of risking a serious additional sentence – stabbing a rapist or a snitch, say – in order to benefit one’s fellow class of solid convicts became increasingly rare.

I don’t know how much of this shift Anthony was aware of when he arrived on the Row. It can’t have been easy touching down in the wake of total media saturation on the details of his misdeeds, even with the death of the old school convict code. Just because most men would no longer take it upon themselves to extrajudicially punish a rapist doesn’t mean that such offenders are well-regarded, however. He probably knew that in the prison hierarchy, rapists are the faces at the bottom of the totem pole, because he decided early on that he would benefit in myriad ways if he inflated his body count and amped up what he believed to be signals of psychopathy. “Being a psychopath is like being Clark Kent,” he told me during one of our very first conversations in 2009, “except that nobody wants to meet what comes out of the phone booth.” This tactic had widely divergent results on targets inside the prison (convicts) versus those outside (civilians), with the former being largely unimpressed, and the latter swallowing hook, line and sinker. I don’t think he ever really seemed to appreciate just how badly his message was failing with those of us in white – a remarkable fact that I think says quite a lot in and of itself.

Anthony did end up having massive success with two deeply interwoven groups in the freeworld: Serial killer “groupies” and fans of murderabilia. That this first group exists is something that I was peripherally aware of prior to my arrival in prison, though I had no idea of just how many of these people were out there, or the extents they will go to in order to get close to their… friends? Idols? I’m not even sure how to describe the nature of these relationships. I’ve known a number of serial killers over the years, and to a man they all enjoyed sharing their fan mail, to a degree that I think is very indicative of the sorts of ego problems such men have in their cores. I suppose “guru” might be the closest term for how these men are perceived in this community, a point that I humbly suggest you might want to consider for a long moment. T-Bone had a collection of such acolytes who sent him money and came to visit him, including a woman who claimed to be the paramour of Richard Ramirez, California’s so-called “Night Stalker”. T-Bone’s primary means of impressing this crowd centered on his vague, wink-and-nod insinuations of responsibility for several dozen unsolved rapes and murders along Highway 45 in Houston. Dubbed by the press as victims of the “I-45 Strangler”, the bodies of a number of these victims were discovered adjacent to important locations from Shore’s life: A block over from a home he lived in as a boy, in the lot next to a telephone system substation owned by his former employer. In many cases, the victims were killed in similar ways to the crimes Shore was convicted of, and matched the physical characteristics he is known to have preferred in his victims. To my knowledge, Anthony never explicitly took credit for these murders, but he nudged up pretty close to the line numerous times in my presence. I honestly don’t know why he thought this would impress any of us. It seemed a very weird thing to brag about.

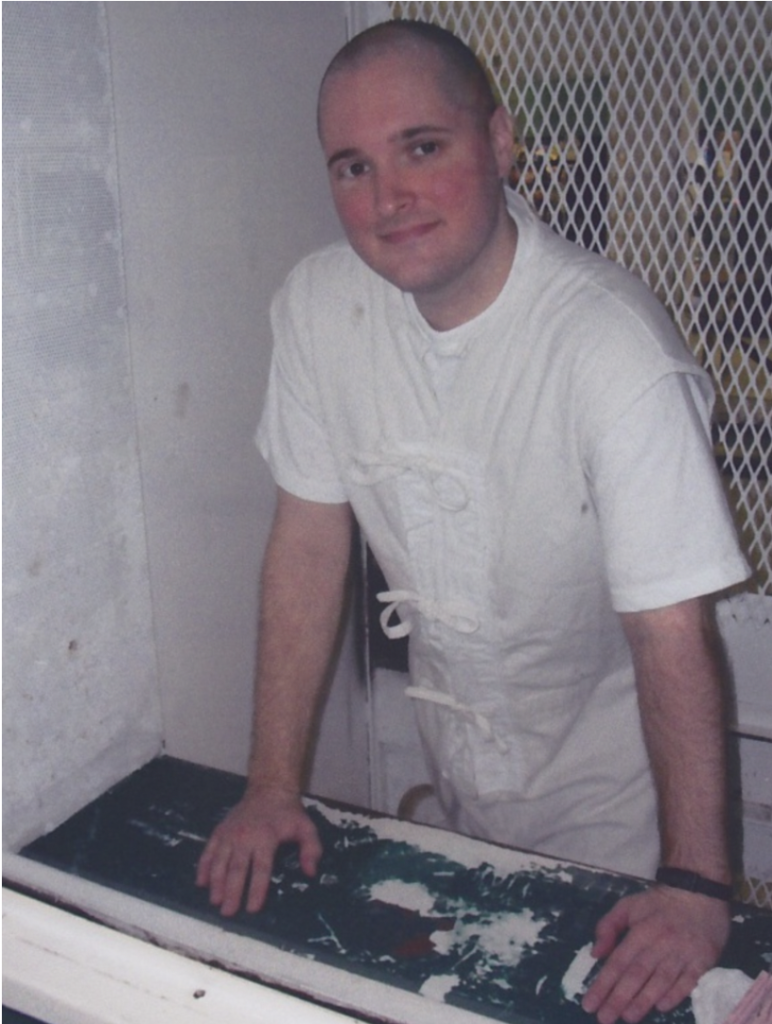

For all that, he really was an exceptional artist. He was probably one of the top five or six artists with a pencil on the Row. Consequently, he had deep connections in the murderabilia community. I’m not privy to the details of how many pieces he sold per annum (and it would be inappropriate for me to mention the names of these vendors, as I have an ethical objection to their existence and, therefore, have zero desire to gift these people with additional eyeballs or dollars), save to say that I never knew T-Bone to miss a trip to the commissary. His bags, when delivered, were always amongst the fattest in the section. When you could get him to talking about technique, he really was fairly pleasant: Bright words from dark matter. I was raised in a conservative home, so I have enough of the whole Horatio Alger mythos woven into my worldview to appreciate the fact that T-Bone was able to live pretty well in prison based off his talents, even if I disliked his methods. It’s hell here if you are poor, and there’s plenty misery enough without going hungry at night.

It bothered me that I couldn’t quite decide whether I believed Anthony might be willing to sacrifice Larry for a few extra months of life, but he left me with enough doubts about his internal ethics that I had to operate under the hypothesis that anything I said to him could be twisted and molded into a more presentable shape for delivery to the police. The worst part about all of this was that this was the first time in a decade that I’d actually perceived T-Bone as being dangerous. A little known fact about the condemned in Texas: None of us are sentenced to death for the crimes that produced our arrests. Murder alone is not sufficient to get you the needle. Instead, jurors must peer into their magical crystal balls and determine “whether there is a probability that the defendant would commit criminal acts of violence that would constitute a continuing threat to society” [Tex. Code Crim. Proc. Ann. Art. 37.071(2)(b)(1) (Vernon, 2005)]. We are, in a very real sense, killed over prophecy (I will discuss the concept of “future dangerousness” in more detail in a later chapter). Whatever else can be said about Anthony, he simply was not a physical danger to anyone in the prison environment. Aside from the respect garnered for his art, he didn’t really impress those of us in the cells. His serial killer schtick came off as being kind of stale, the sort of thing you’d create if you’d watched a bit too much Criminal Minds. In the great menagerie of the Polunsky Unit, he was a small, scurrying thing: A field mouse, a newt. It disappointed me that a shrew with grand pretensions was putting an entire section in check, that my last months of life were going to be spent walking on eggshells, wondering if my name was going to be discussed every time officials pulled him out of his cell for a chit-chat. He had to have known the reason that Deathwatch had descended into this frigid wasteland, and the fact that he wasn’t doing anything to alter this didn’t help his side of the story, whatever that might have been. It was like he was conceding the high ground to the rumor mill.

Only one other light flicked on during my two hours in the dayroom, that of Richard Tabler in 14-Cell. Richard was the only man on Deathwatch who didn’t have an execution date. Instead, the administration had placed him in the section years ago after he had used a smuggled cell phone to call John Whitmire, one of the most powerful senators in state government and head of the Senate’s Criminal Justice Committee. I’ve heard dozens of different stories about this call, but at least a few of them included the fact that Tabler may have in some way threatened the Senator’s daughters, a profoundly stupid thing to have done if true. Whitmire’s response was about what you’d expect: Mass shakedowns; months of lockdown; and a sea change in policy, none of which was in any way positive for us inmates. Within six months, millions of dollars had been apportioned for a massive surveillance system for the Polunsky Unit, thousands upon thousands of cameras that would serve to scare off the few decent guards remaining and usher in an era when disciplinary cases were handed out like Halloween candy. For months, the whisper-stream reported that Tabler was being regularly removed from his cell to speak with various officials from Huntsville. Almost invariably, raids on the rest of the Row followed. I never jumped on the “Tabler = Snitch” bandwagon, since I had no firsthand knowledge of what he was or was not saying, but neither did I care to have anything to do with a man who had single-handedly gut-punched our quality of life, and who by some reports seemed to enjoy the fact that everyone was now miserable. I saw out of the corner of my eye when Tabler came to his door to see who was in the dayroom, but I ignored him, focusing on my workout. After a moment, he turned away and vanished. I figured it was all for the best.

After my run, I went and put my back against the bars, staring at the cells, the picket, the dayroom cage, the run. This was likely to be the last home I would ever know. I watched the doors, noted which cells were empty, which were occupied. I listened to the silence – so rare an occurrence in that place that it seemed almost creepy to me. I thought about what it meant, the way everyone was sealing themselves off from everyone else so that they could die alone, prioritizing freedom from any last-minute drama from the police over any sort of human companionship or solidarity. This is a hell of a way to die, I said to myself, looking at 10-Cell, my final cage.

A hell of a way to die.

3 Comments

Dividing By Zero-Part Three - Minutes Before Six

March 12, 2023 at 6:46 pm[…] To read Part 2 click here […]

Martina Quarati

August 11, 2022 at 3:27 pmI have no words. Simply mind scattering and moving. “ Cherish your ignorance, O unknown and unknowable reader of posterity: Cherish your fucking ignorance.”

LD

August 9, 2022 at 4:58 amIncredible writing. Mr.Whitaker you should be allowed to write novels. Best sellers list. Without question.