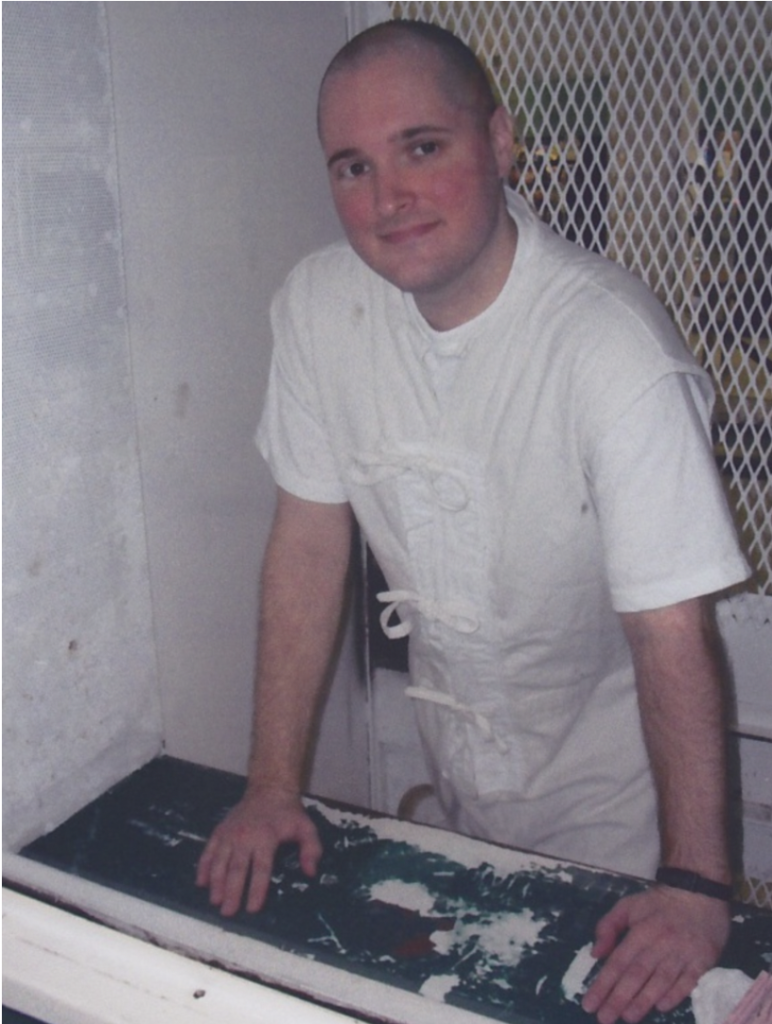

Artwork by Miguel Angel Paredes

Perhaps fittingly, it was fire that started to bring us together. I’d begun picking up the faint odor of something burning a few minutes before, but it took me an embarrassingly long time to recognize that there was something distinctly metallic about this new scent. Eventually the last of my cerebral horses straggled across the finish line and I walked to my cell door to investigate.

Fires are pretty commonplace in prison. Say you have a problem: Maybe your toilet is leaking. You’ve tried to explain to the pod officers that water is all over your cell, but it’s pretty clear that they don’t give a damn. Technically, they are supposed to call a ranking officer to the pod to investigate, prior to putting in a call to add your issue to the maintenance log. If the officers don’t feel like doing this, you have to figure out a way to motivate them. Fires are a sort of conjuring trick: Using newspapers, some wire, and your electrical outlet, you now have a blaze burning that you can shove out the door onto the run. Voilà! Rank is now on the pod. There may be hell to pay – there might be a 90-day all-expenses paid vacation to F-Pod (a place that is, if not precisely the literal fetid asshole of hell, it certainly has a good metaphorical view of it) – but at least you’ve managed to get the administration’s attention. This wasn’t burning paper I was smelling wafting about Deathwatch, however, nor towels, nor sheets, nor any of the other sundry items we convicts torch in the midst of our little tantrums. Whatever was burning, I decided quickly, there was quite a bit of it. Mere seconds later the banging began: Loud, incessant crashes, as if someone was hitting the metal bunk in the cell below mine with a sledge hammer.

I couldn’t see much of anything from the front of my cell, save that the man in the dayroom was staring intently at something going on in the first few cells near the corner. One has to be in a certain kind of mood to initiate conversations with John “Batman” Battaglia, to put things delicately, and I just couldn’t summon up the necessary defense mechanisms to make the endeavor worthwhile. My direct neighbor to my left, he’d finally acknowledged me for the first time the night before on my way back from the shower. John could be difficult. A highly successful CPA from Dallas, John had killed his two young daughters while their distraught mother listened on the phone; he then went and got tattoos commemorating them just before his arrest. A case like that isn’t going to make one many friends in a place like prison, and John seemed to go well out of his way to ensure that his reputation never improved over time.

Take the world’s most terminal case of oppositional defiant disorder, and graft it to the sort of moneyed arrogance that one rather thought died out with the British Raj. Layer this with an intentional crudity that was highly deliberate, a desire not to épater la bourgeois but rather to grind its face into the muck and mire until it stopped twitching. This vulgarity was a highly calculated device, a scalpel that he used with glee against the hegemony of political correctness that he believed was suffocating the America he loved; in his words, this was his contribution to “postmodernist theory”. Add to this a hyper-complex, paranoid fantasy world populated with myriad powerful and murky social forces that were personally involved in his execution, and you have a basic idea of how complex he could be to handle. Only a basic one, mind: John was far too weirdly intelligent to be summarized in a single paragraph.

For a number of years, he liked to strut about the dayrooms wearing a cravat he’d fashioned out of a handkerchief, just so he could invite conservations whose sole purpose was to mock the “cretins” (his favorite noun, without question) who didn’t have his fashion sense or even know what a cravat was in the first place. You didn’t really talk to His Nibs; he spoke to himself while standing in front of you, the rest of humanity being relegated to the status of mere cameos in the drama of his solipsism.

For all of that, I didn’t really dislike the man. He was incredibly unique, a point that goes quite a ways in my book. People are never just one thing, if you think about them long enough. Everyone thought John was an ass, but I think most everyone also knew that he had a bruise where his soul should be. I don’t know how it got there, but it dominated him. No one is the person they could have been when they are coming from a place of such woundedness. For what it’s worth, I don’t think he really understood why he’d killed his daughters. For those who want to hear about how he was a man tormented by his deeds, be comforted: His prison life was one filled with regret. I always read his behavior as a gigantic flashing neon sign, asking people to leave him alone. I read this, and mostly granted him his wish. Silence was our armistice.

Juan Castillo was a kinder, more forgiving soul than I (or more of a masochist, or both), so he took the bullet for everyone on the second floor and broached the subject of the racket.

“Oh, there’s some kind of maintenance crew in 3-Cell,” Batman said, looking up at all of the faces staring at him, feigning surprise, as if he hadn’t known we were all standing there waiting for a report. You could see him gearing up for one of his performances: happiness at having the stage, mixed with a deep disappointment over the lack of patrons capable of appreciating his art.

“You know that saying about how when the only tool you have is a hammer, all problems look like a nail? Well, these imbeciles apparently haven’t learned about the existence of saws yet, because they are trying to remove the bunk in 3-Cage with a cutting torch and a hammer.”

“I got yer ‘imbecile’ right here, bitch,” a rusty jack-knife voice responded from inside the depths of 3-Cell. I mentally pictured one of the maintenance inmates, white uniform covered in grease stains, picking up a hammer and pointing it menacingly.

“Yeah, yeah,” John waved dismissively with the back of his hand (off with his head, guards!), and I couldn’t help but smile. To my surprise, T-Bone got involved in the conversation, relating a story about how a similar crew had once attempted to fix a leaking pipe with nothing but duct-tape. Mr. Rayford chimed in with the time they installed a new temperature gauge on the boiler for C-Pod incorrectly, and how this had caused the entire mechanism to explode. Even Tabler injected a story or two, and nobody rebuffed him. Every few minutes the bars and southeastern section of One-Row would light up with flashes of blue light, and we’d get hit with the acetylene stench of metal melting, burning, setting. It wasn’t exactly a deep conversation, but it struck me in the moment as being kind of funny, the way we were huddling around that blue campfire, united in our attempts to keep the wolves at bay by sharing stories of the TDCJ’s ubiquitous stupidity. “Nothing binds like mockery”, I wrote in my journal: an ugly truth rendered useful in an ugly place. Only Ruben “Mexican Scooby” Cardenas failed to join in, though Juan attempted to call him on a few occasions. Given that he was only five days away from being killed, I figured he was beyond caring. Still, this was the first time I’d heard the section actually involved in a real conversation, and I hoped this was a sign of thawing and not a mere aberration.

John’s vaunted interpersonal skills were obviously not going to be producing any answers on what fresh hell they were clumsily constructing in 3-Cell, but Mr. Rayford went to the dayroom next. Between his questioning and my own later that afternoon, we were able to piece together the story that the administration was expecting the arrival of a particularly violent, escape-prone inmate, and wanted to create a special cell to house him. “We’re making us a Level 5 cell,” one of the pod officers told me at one point. Given that the worst behaved inmates were only classified as “Level 3”, I think this was an attempt at humor – though I’m not entirely certain. Over the course of the next week, they removed the desk, replaced the standard bed with a shorter one that contained far less total metal involved in its construction (if one is suitably motivated, the iron from the bunks makes a mighty fine shank, I’m told), and laid a piece of heavy stainless steel over the inside of the cell door and that of the shower on One-Row. Since this latter added several hundred pounds of weight to these doors, this produced something of a comical moment when the maintenance crew realized that the doors would no longer close correctly. This necessitated the removal of the doors, the strengthening of the frames, and then a three day, nearly epic struggle to fit the doors onto said new frames. They might have had an easier time of it had they been allowed to use more than a grinder, a cutting torch, and the now-infamous hammer. Metal grating was then added to seal the windows on the doors, and a feeding box welded into place. Just when we thought the remodeling was complete, a bunch of bigwigs from Huntsville came by for an inspection. The following morning the maintenance crew was back, drilling a hole into the concrete floor so that a support anchor could be welded onto the door. Nobody on the crew had ever used this drill before, and by the time they were done for the day, the paint on the walls was peeling off in strips from the sheer acidic weight of the curses that had been aimed at them all day. Whoever this prisoner was, we all murmured, they were definitely not taking any chances with him.

That following Monday I had my first visit with my father and stepmother since my date had been set. That was perhaps the first time in all of my years behind bars that I actually dreaded going to visit. What does one say? All you can do is put on a brave face and try to spin the news in such a way that it lessens the fear and pain one’s family is going to be feeling. My story was that I was just very tired, and that the State was doing me a favor. All of the best lies have a kernel of truth embedded in them, and this was no different: I really was exhausted; a part of me really waslooking forward to ending my time in prison, no matter what that end actually entailed. Kent and Tanya must have resolved to do the exact same thing, because they merely nodded sadly over my rationalizations. They knew what my last-minute plans were – we’d been discussing them in theory for years – so they took solace in the idea that we weren’t completely out of the game yet. Still, I could tell how tortured they felt. I suspect every family member feels this way, but my case has some fairly atypical facts that added to this sense of justice corrupted.

*****

There are essentially four justifications trotted out by supporters of the death penalty when attempting to vindicate capital punishment’s continued existence in America: Cost effectiveness, incapacitation, deterrence, and retribution. The first has always been a sham, and has been fading out of use in recent decades with all but the least educated of pro-DP activists. Every single time a legislative sub-committee or body of scholarly researchers conducts an analysis of the death penalty, it is shown to be far more expensive to execute an offender than to sentence them to life in prison. In “Money for Nothing? The Financial Cost of New Jersey’s Death Penalty”, Forsberg found that the state had spent $253 million on its capital scheme during the years 1982 to 2005. The results? Of the 197 capital trials conducted, 60 death sentences had been handed down. Of those, 50 had been reversed on appeal, leaving ten men still under sentences of death. Not a single execution had taken place. While it is impossible at this juncture to say what was in the minds of all of the individuals involved in New Jersey’s decision to abolish the death penalty in 2007, this report almost certainly contributed.

Similar results were reported in Brambila and Migdail-Smith’s 2016 “Executing Justice: A Look at the Cost of Pennsylvania’s Death Penalty”, where it was estimated that the state had spent in excess of $800 million on a system that had managed to execute a whopping three inmates. Each death sentence was found to cost around $2 million, while the cost per execution was in excess of $200 million. In California, Alarcón and Mitchell found in 2011 that from 1978 to 2010, the state had spent more than $4 billion on a capital scheme that produced a mere 13 executions.

How could this possibly be the case? Death penalty trials take place in two parts, guilt/innocence, and punishment. Non-death penalty cases tend to end in plea agreements, meaning the expense of an actual trial is avoided. When a death penalty trial does go the distance, it costs far more than a regular murder trial, to the tune of an additional $116,600 to $493,500 for the defense and an additional $7,212 to $217,000 for the prosecution, according to Frank Baumgartner’s Deadly Justice. Not included in those prosecution totals are the added expenses that police departments rack up in investigating cases that the DA’s office has signaled as being death worthy. I have no figures for these totals, as local departments do not report them. It will suffice to say that they are significant, often involving thousands of overtime man-hours. In addition to lawyers’ fees, death penalty trials tend to use far more expert testimony than non-death trials; Baumgartner estimates this adds between $49,000 to $77,754 per case, depending upon the jurisdiction. Death penalty juries must go through a unique “death qualification process”, which involves weeks of interviews, involving all manner of court personnel: Judges, bailiffs, stenographers, etc. The appellate process for death penalty cases is statutorily mandated in America, meaning a wide array of additional expenses over regular murder cases: For direct appeals, this adds an estimated $13,561 to $340,000. For postconviction appeals at the state-level, tack on $43,000 to $300,000 per sentence. For postconviction appeals at the federal-level, add $96,000 to $1.1 million per case. The variance found within these totals is largely political: States dominated by Republicans tend to have shorter, less developed appellate processes, whereas states with a liberal bent usually have longer, more factually-based processes. The response to this disparity from conservative politicians and activists is to complain that the appellate process is simply too lengthy and is in need of “reform”.

There have been 163 exonerations of death-sentenced inmates since the Gregg decision and counting; by the time you read these words, that number will almost certainly be higher. Each of these exonerations required the sustained effort of dozens of lawyers, experts, and specialists; each of these efforts was conducted against state power, a power that always fought tooth and nail against the release of information that ultimately proved innocence. Each of these cases needed every minute allotted to them by the court process. If this process had been shortened in any way, many of those 163 human beings would have been executed. (Between 2010 and 2015, for example, the average exoneree spent 24 years on the Row; Ricky Jackson spent 39 years.) We don’t need less review, we need far more of it, especially in the South. Given all of this hard data, hardly anyone on the Right bothers with the cost effectiveness argument anymore, and it has effectively been conceded to the abolitionists. Bullets may be cheap, as many pro-DP activists seem to love to opine on message boards, but the death penalty can never be, so long as society cares in the tiniest way about not executing the innocent.

Similarly, arguments for incapacitation seem to have gone out of fashion of late. The idea here is that society simply needs to execute certain people in order to remove their variables from the equation of the prison population. Some offenders simply can’t be rehabilitated, it is argued, so it’s better to be done with them once and for all. The problem for this view is that over the past few decades, thousands of death sentences have been overturned nationally. The vast majority of these men have been moved into the general population environment, and their behavior has therefore been documented and quantified, just like the rest of the offender population. Studies have consistently shown that murderers are amongst the best-behaved prisoners; this perhaps surprising fact holds true across all fifty states, and it has remained true since such statistical comparisons began to be recorded.

I’ve heard quite a few reasons for why this may be. There’s probably something to the argument that murderers, faced up front with long sentences, recognize prison as their new long-term home and settle into the penal environment in a way that other prisoners with shorter sentences do not. For someone with a mere five years to do, prison is a temporary inconvenience – old dreams are simply put into abeyance for a time. For someone with decades of time to serve, prison is a reality, and old dreams must be killed in favor of much smaller ones. It is also probably true that the act of murder tends to be the result of a long-duration confluence of tensions and pressures in the life of the murderer: The act is the culmination of a multitude of circumstances that are unlikely to occur again over the course of a human lifetime. A thief may commit dozens of criminal transactions over the course of their criminal life, but the vast majority of killers commit only one such act. Although the impact of their actions is obviously the worst imaginable, it may prove to be easier to reform a person who has indulged in one criminal act compared to someone who has made a career of them.

These and other explanations may all be true. After having been responsible for death and having lived around several hundred men about whom the same can be said, I think guilt has far more to do with the relative calmness found in most incarcerated killers than anything else: A point I doubt most Americans understand. I can’t blame them, though, as most of what the average citizen “knows” about killers has largely been served up to them by movies and television. The simple fact is, I have never met any prisoner who approaches the concentrated evil found in the average antagonist of the police procedural shows that run nightly on CBS. I’ve never met a “sociopath” as they are portrayed on the screen: Hyper-intelligent, possessed of an almost autistic focus on doing damage, blessed with myriad talents and skillsets that they have twisted in inventive and horrifying ways to the grand purpose of hurting people. I’ve heard and seen prosecutors try to create such images out of the men on Death Row – of that, I’ve seen multitudes. I have yet to listen to a single “true crime” episode on channels like Investigation Discovery that adheres to reality; I’ve read and studied caselaw for a decade, worked my way into the minutiae of dozens of cases, and it was only through a supreme effort of imagination that I could connect the objective facts of each case to the fantasies created for mass consumption. The truth is always messier, more human: People kill for stupid reasons, for irrational hates and fears, and, perhaps most horribly, for loves. They kill over confusion, out of desperation, and for reasons that they are never able to explain afterwards. They kill over final straws that are always recognized afterwards as being mere straws. One of my last neighbors before I was moved to Deathwatch was sentenced for killing his girlfriend. When asked why he’d shot her, he could never explain it outside of referring to small irritations: They were short on money, and he felt she thought he was a failure as a provider; he thought she was pulling away from him, perhaps in favor of a mutual friend; etc. Once, after a few bottles of hooch, he broke down weeping and started telling me about how it had been raining non-stop for a week and he didn’t know why that had made him so angry, but that was the real root of the argument that ultimately spun out of control. When I loaned him my copy of Albert Camus’ The Stranger, where Meursault kills the Arab for a multitude of reasons that were brought to a boil by the glare of the sun in his eyes, he wrote me back a kite that contained six words: “It’s true. It’s true. It’s true.”

I’ve only met a handful of the men sentenced to death in Texas who I would ever consider labelling as “evil”, and these men are – down to the very last – sick human beings not living in the same universe as the rest of us. If you could somehow load all 220-or-so of the men on the Row up with sodium amytal and ask each of them who the truly, inveterately dangerous men were, you’d get the same eight to ten names. If you managed to conduct the same experiment with the officers, the names wouldn’t change much, either. If you asked both groups to describe this cohort in just a few words, you’d end up with synonyms for insane: crazy, throwed off, loco de la madre. I’m sorry that’s not more exciting. It wouldn’t make for good television if the things that go bump in the night talked to themselves for hours before their criminal acts about the “NSA biomorphic surveillance machines growing in the walls” (actual words of inmate Travis Green, #999373), or were so strung out on drugs that they were barely cognizant of their actions. We need our monsters to be crueler, more vicious than this, apparently. (Although I’m not really clear on why, to be perfectly frank.) Unfortunately for the incapacitation crowd, however, murderers turn out to be the prisoners who are most fundamentally changed by their actions, and the most likely to be drowning in a sea of remorse. As these numbers began to pile up, the sorts of people who once preferred this argument have shifted to others, perhaps realizing that the same data that argue against incapacitation might also prove fatal to the myth of the pure evildoer that powers the entire capital punishment project in America.

Deterrence is the third justification for the death penalty, the one preferred by the so-called intellectuals on the Right. It makes a certain kind of sense, the idea that criminals might give second thoughts about committing a murder if they knew that a vial filled with compounded pentobarbital was waiting for them at the end of the line. Problems accrue when you begin to review the literature or speak with the men involved: Individuals who commit murder are often drunk, high, or mentally ill, and are thus incapable of performing the sort of risk analysis necessary for a deterrent effect to have an impact. In any case, a death sentence is rarely the result of a homicide. In Texas, which easily has the most active death penalty machine in the western world, only between three and six percent of all eligible homicides end up in death penalty trials, and only 1.11 per 100 end up in an actual execution, meaning the calculation men are making – if they make one at all – is really between getting caught or not. Nationally, there are in excess of 10,000 homicides per year, but with only around 1,500 actual executions total since Gregg, this averages out to less than three dozen per year across all fifty states: Hardly a shadow cast over future actions. On top of this, executions are seldom spoken about on the news down here in the Yee-haw Republic, meaning that there are many people on Death Row who weren’t even aware of the existence of capital punishment when they committed their crimes. Since Texas now has a Life Without Parole (LWOP) alternative, the so-called rational calculus of deterrence is really the likelihood of death versus LWOP, not death versus non-arrest. In an ideal world of perfectly rational actors, deterrence might play a role in crime reduction. In our world, the truth is more muddled.

Deterrence has been a hot issue for decades amongst criminologists and sociologists. Hundreds of longitudinal studies, cross-state comparisons, and interrupted time series (i.e., before-and-after studies) have been conducted since the 1970s. Both sides of the abolition debate have data they can point to that seem to back up their positions. The problem is, you don’t have to travel very far into any of these studies before their shoddiness becomes apparent, especially those that rely on “price theory” as their philosophical foundation. Read the small print of the methodology section of each study, and one will begin to notice huge variances in estimates and relatively lax confidence intervals, which add up to huge prediction errors. This isn’t just bad social science, it’s patently awful mathematics, driven by researchers who believe “common sense” notions about deterrence promote the moral necessity of executions.

Given the conflicting narratives produced by these camps, the National Research Council, a wing of the US National Academy of Sciences, convened a blue-ribbon commission to study the subject. Their charge was “to address whether the available evidence provides a reasonable basis for drawing conclusions about the magnitude of the effect of capital punishment on homicide rates”. The upshot of this report was that the vast majority of these studies barely reached the level of junk science, and that there simply wasn’t enough evidence to demonstrate that there was such an effect on potential criminals. One of my major problems with some of these studies is actually really simple: They claim to have strong assessments of potential murderers’ perceptions of and response to the capital punishment component of a sanction regime, i.e., a model of how criminals think – as if all potential murderers thought about crime, morality, sin, responsibility, and just deserts in exactly the same way. If there really was such a “code of the criminal” we’d have figured out America’s crime problem decades ago. No scholarship should be this ideological.

I’m afraid I have been guilty of misreading these data in the past. On at least two occasions that I can recall, I have argued that the fact that the South has the highest murder rates in the nation and the highest execution figures proves the non-existence of a deterrent effect. This may in fact be true; the abolitionist crowd certainly seems to think so, and has quite a few statistics at their disposal. Texas, with the highest number of executions in the nation, has a higher murder rate (1.91 per thousand population) than all of the states in the nation without the death penalty (1.53 per thousand). This is true for all of the states in the South (Louisiana = 3.65 per thousand, Alabama = 2.19 per thousand, Georgia = 1.91 per thousand, South Carolina = 2.01 per thousand, just to name a few). It still may be true, however, that a minor deterrent effect exists but is simply being washed out by the elevated levels of across-the-board violence found in the states of the old Confederacy. We just don’t know. And that is the point: Nobody knows. So, if someone attempts to sell you on the idea that they’ve proven or disproven a deterrent effect, you’d be wise to turn to your bologna-detection apparatus, as it is almost a certainty that this person is trying to sell you an ideological concept wrapped in the guise of valid statistical science.

The final argument in favor of capital punishment, and easily the most popular with the public, especially in southern states, is retribution. This hardly requires explanation. “An eye for an eye” has been with our species as an abstract concept for a very long time, even if the only area of our criminal justice system where this mantra is invoked is in discussions of the death penalty. We don’t, for instance, kill regular, non-capital murderers; we don’t even execute the overwhelming majority of capital murderers. We don’t advocate for rapists being raped, thieves having their property stolen, or the beating of those who assault others, at least not officially: In unofficial terms, society does seem to be content to turn its back on such extrajudicial sanctions taking place daily in our prisons, just as long as these things take place out of sight. As the concept of lex talionis has been somewhat softened since the Enlightenment ripped out Christianity’s fangs, it has been forced to find new ways of justifying itself. For a while, scholars of “Retributivism” (once again, their term, not mine: A scholar’s work isn’t complete until they’ve “problematized” normal terms with unnecessary “isms” and “izes”) tried to argue that their goals were rooted in the value of dignity: Inflicting what they deemed “proportional punishments” on criminals respected the offenders’ “dignity” by treating them as the autonomous author of their own punishments, a point I referred to in a different way in Part One. Judges apparently bought into this sort of rubbish, but it never really caught on with anyone outside of the Academy. Instead, lay support for capital punishment has in recent decades been almost entirely couched in the language of the victims’ rights movement. Killing people apparently heals: “closure” (whatever that actually means) is now the foundation upon which rests the capital punishment apparatus in the United States. “We do our difficult duty for the victim’s family”, District Attorneys regularly claim on the news, totally omitting mention of the new set of victims an execution inevitably creates. The family members of the condemned are seldom mentioned in news articles. No photos of wailing mothers outside of the Walls Unit ever grace the pages of local newspapers. I used to think this absence indicated the presence of a covert sense of shame felt by society in general. I’m not sure I really believe we are capable of feeling shame anymore, given the political decisions being made by many of our fellow citizens. Maybe describing the death penalty as a victimhood transference program is just too controversial for beleaguered media organizations wary of losing ad revenue. I think I’d prefer that to the alternative: that we really just don’t give a damn anymore.

Whatever the case, the media would not be able to avoid talking about the new victims created by my execution. In my case, the new victims were the old victims, and they had no intention of keeping their mouths shut.

I was convicted and sentenced to death for masterminding the 10th of December 2003 killings of my mother and brother. My father was also a target, but he survived that attack and went on to forgive me for my part in the plot, a tale he told in his New York Times Best Seller book, Murder by Family. This remarkable stance had its roots in his Christian faith. I suspect it wouldn’t have mattered much if he had been Muslim or Jewish or Buddhist or a follower of the Flying Spaghetti Monster. Some people just have an inherent goodness of character that holds up all of the beliefs and creeds they build on top of that core. In every war, every conflict, one can find people who are capable of looking directly into supernovas of pain and evil and never lose sight of who they are inside. I’m far too clumsy a wordsmith to even approach this subject; everything I write about my dad always ends up falling short, makes it sound like his journey was far simpler than it was in reality. There were moments after the deaths of my mom and brother, and before my eventual flight to Mexico, where I witnessed my father break down, shattered into innumerable jagged shards. I don’t know how he ever managed to tape himself back together. He walked through hell in a gasoline trench coat and came out the other side unsinged. If I have ever once borne my punishments with the tiniest hint of dignity, if I have ever been successful at overcoming my past and becoming something better than I was, it is largely due to his example.

This could have been a remarkable story of love and forgiveness. The elected District Attorney of Fort Bend County, John Healey, was not so minded, and chose to pursue the death penalty over the increasingly strident objections of family members from both the maternal and paternal sides of my family. On one occasion, my father fell to his knees in Healey’s office and literally begged him not to pursue a course that would only bring him more pain. Healey was unmoved. This produced a state of affairs where the elected DA of a politically conservative county began treating the surviving victims of a horrendous crime as if they were defendants themselves. This, to put it lightly, is simply not done, especially in this supposed “victims’ rights paradise”. My family searched long and far to find a case with a similar factual landscape where such a decision was made and came up empty. Indeed, in every patricide case we could find, if the remaining family members informed the DA that the death penalty was not desired, it was always taken off the table immediately. I don’t think any of us understood just how subjective the process is by which DAs determine which cases they intend to seek death on. Different states have lists of “aggravating factors” that designate crimes more worthy of death (twenty-nine, for example, promote the seeking of death if the victim was a peace officer; twenty-six if the crime included sexual misconduct, etc.), but at the end of the day, it is still the elected DA who has sole discretion to determine who is tried for the ultimate punishment. This power was on full display in my case when Healey declined to seek death against both the actual shooter, Christopher Brashear, and his accomplice, Steven Champagne.

To this day, I have yet to hear a convincing argument for why Fort Bend would choose to spend millions of dollars and countless man-hours seeking death on a defendant whose execution wasn’t desired by anyone connected to the case. My father is convinced that this was a political decision, hastily made by Healey, that they were constitutionally incapable of reversing course on once committed to. He’s probably correct, as it seems like DAs in Texas have some sort of allergic reaction to ever admitting they made a bad decision. It’s a common theme in cases where a former prisoner is formally exonerated: DAs insisting that they were still convinced of guilt, long after incontrovertible scientific evidence has proven otherwise. Texans still seem to be in love with the image of the stern, unyielding lawman, even when these figures are shown to make regular and repeated errors in judgment. I don’t know why. People keep telling me we are a frontier people, but this seems a lame explanation. Fort Bend is a place of gated neighborhoods filled with stucco monstrosities, luxury SUVs, and designer handbags; the only frontier most of these people care about is the exploration of a higher tax bracket.

Several lawyers who regularly practice in Fort Bend have told me over the years that they were positive this decision was largely the result of Fred Felcman, the county’s First Assistant District Attorney, pressuring Healey. Felcman has been either lead or second chair prosecutor against every capital murder defendant for the past thirty-five years, or some fifteen cases. He even comes packaged in the appropriate costume for the role, with cowboy boots and a Wyatt Earp mustache. For his steadfast pursuit of the death penalty, Felcman was given the Board of Directors’ Trial Award for Outstanding Advocacy in Capital Cases by the Association of Government Attorneys in Capital Litigation in 2012. When he recommended Felcman for the award, John Healey opined that “Felcman’s toughness is offset by the tenderness he feels towards victims and their families”, a point that I’m not entirely certain my family would agree with.

The truth is, I don’t honestly know what these men really believe about why they were so relentless in seeking death against me. The court process is at its beating heart an adversarial one. Everything officials say in public is tactical, an attempt to influence the resolution of the case via the plea bargaining process, as well as a reminder to their voting base why they elected these officials in the first place. I’ve heard the rhetoric, but I doubt I’ve ever heard exactly what these men thought about my case. I want to believe that during the first months of my time in the county jail, Healey and Felcman understood that they really didn’t want to revictimize my father, that they just wanted to keep the shadow of the gurney projected in full view so that they could get me to sign for the sort of Mt Everest sentence that they were known to prefer. I hope that is not naïve on my part. Even after everything, I still want to believe there is more decency in them than seems obvious.

What I do know is that from the moment of my arrest I had been attempting to convey the message to Healey that I was desirous of admitting my complicity in my crime and was willing to sign for multiple, stacked life sentences in order to prevent my family from having to endure the ordeal of a trial. I don’t believe this message was ever appropriately handled, unfortunately. Immediately after my arrest, a highly-regarded attorney in Houston took up my case. A family friend of my maternal uncle, his firm agreed to handle most of the initial contact between my family and the State. He strongly believed that the State would offer a plea agreement, and while he never admitted this to me, I believe he withheld my willingness to confess from the prosecutor because he felt it would weaken my position.

These expectations seemed to be confirmed during a supposedly random encounter between this attorney, his assistant, and Felcman at a local Best Buy. (I’ve tried to get details on exactly who called for this encounter to take place and why they chose that particular store, but have come up empty.) During their little chat, Felcman mentioned that he would take the death penalty off the table if I wrote out a statement of guilt, explaining my role in the crime, clearly and concisely, without any attempt at argument or justification, and, especially, without any mention of remorse. This was reported to me on a Friday afternoon by this assistant, and I spent all weekend writing my confession out, in full expectation that someone was going to be picking this document up from the jail for delivery to the DA. I didn’t hear from my counsel for some time. When I finally did, I found out that they had written this “proffered statement” themselves, that it had contained abundant legalese, and that this format had so incensed Felcman that he was now refusing any plea agreement whatsoever. This attorney told me later that he believed Felcman never intended to keep his word, that the whole agreement had been a lie. I thought at the time (and still to this day believe) that he said this merely because it made him look less like a fool. Since the plea bargaining process was now a smoldering wreck, his firm backed away from my case. It had always been understood that I could not afford this man, should my case go to trial. I never expected him, however, to drop a bomb on the plea agreement process and then vanish. Worst yet, Felcman then used portions of this proffered statement against me and my father during cross-examination at trial. When I tried to point out that I hadn’t written the proffer at all – that the document he had handed to me was written by lawyers and that the one I had written had never been submitted – he responded with a question that wasn’t really a question about whether I realized how insulting it had been for him to have received a statement confessing guilt that had contained zero remorse. The jury never understood anything beyond the structure of the rhetoric: I had apparently done something, something perhaps dishonest, something they didn’t really understand, but it must have been really foul to have made the prosecutor so angry. My attorney never objected to much of anything done by the State, so no one ever explained to them that the entire episode – from the initial meeting to the submission of the statement – had taken place while I was in solitary confinement, that I hadn’t known anything about the details until much later, and that everything had been directed and engineered by Felcman to produce that one moment of theater on the stand.

Once my initial attorney and his firm had departed, I should have gone out and requested court-appointed counsel. I would have received better attorneys than I ended up getting, but I had been hearing such horror stories from my peers in the county jail about these men that I felt convinced I had to hire someone. The man I eventually found was the best I could afford. At the time, neither me or my father knew anything about the law. Access to Fort Bend’s jailhouse law library had been “temporarily suspended” for several years, and it remained closed throughout my eighteen months in that facility, foreclosing any chance I might have had to educate myself. We had no choice but to believe my new counsel when he claimed that he didn’t need a second chair – an assistant attorney whose remuneration ultimately would have been subtracted from his own fee. While I am not aware of any case law requiring a second chair, the American Bar Association strongly recommends a minimum of two attorneys for each capital trial. As far as I have been able to determine, I was the only inmate on Texas’ Death Row who was represented by a single attorney. We also had no choice but to believe this man when he said that he didn’t need the help of a mitigation specialist (an expert, I was later to learn, used in all capital murder trials) or a jury specialist (indeed, my lawyer constantly asked for my opinion of potential veniremen during the selection process). Again, these experts would have reduced his total earnings, a point I failed to appreciate fully at the time.

Perhaps most worryingly, this attorney eschewed any input from mental health experts. In this, I began to harbor deep reservations about this man’s understanding of my case. People don’t commit crimes like mine without some deep-seated psychological problems. My first attorney understood this implicitly, and had hired a highly-regarded psychiatrist to evaluate me. The report he generated highlighted a serious Axis-1 disorder, including profound identity confusion, a history of complex delusions stretching backward in time into my youth, and a strong suspicion of Asperger’s Syndrome. This report was never even read by my trial counsel, and it appears that the sum total of investigation he conducted on my mental health history was a three minute telephone conversation he had with my childhood psychologist, which he would later attempt to lie about during my appeals. His lay impression that psychological experts would hurt me more than help me was objected to by my family – but again, what can you do? If you know nothing about the law, you have no choice but to trust the expert standing in front of you. When the DA’s office was informed that we were punting on what they must have assumed was going to be my strongest issue at trial, they realized that we had left the field open for them to define me in any way they saw fit. Without experts to contradict them at trial, the narrative was theirs to write, and they did so in a way that guaranteed a death sentence. It’s still largely the story that exists in the media today: That I am a sociopath, that I committed my crime in order to obtain a mythical insurance policy payout. To this day, I’ve never been evaluated by a mental health professional from the State. I’ve hired three, and they all said the same thing, which is exactly the opposite of what the State has claimed in interviews for years. Unfortunately, in our courts, more deference is paid to my trial attorney’s supposed “strategic decision” not to hire experts than the actual experts utilized in postconviction appeals. These are the rules, strange as they may seem: So long as a lawyer believes a point, it will always be more important than contradictory information proven by experts on appeal, even if the trial counsel’s understanding of the subject is completely erroneous. The bottom line: by failing to hire any experts or subpoena a single witness during my trial, we had simply made it too easy for the District Attorney. My father’s wishes paled in comparison to four more years of job security.

Even after everything, I don’t believe Healey or Felcman regret this decision. This doesn’t mean that they are unaware that their “hang ‘em high” ethos is fading away into the realms of the anachronistic. These men are not fools; Healey in particular is a man who seems to be aware that his era has passed him by. When nominating Felcman for the above award, he drew a connection between his first chair and Alfred Lord Tennyson’s Ulysses:

“Come, my friends, ‘tis not too late to seek a newer world. Push off… for my purpose holds to sail beyond the sunset… And tho’ we are not now that strength which in old days moved earth and heaven, that which we are, we are; One equal temper of heroic hearts, made weak by time and fate; but strong in will to strive, to seek, to find, and not to yield.”

This is political theater at its best. On the one hand, the one held out to the public, Healey has to be aware that precisely zero of his conservative supporters have read this poem. To this crowd, these lines project an image of Felcman, eyes fixed firmly on the horizon, an immense American flag billowing out behind him. The other hand, the one hidden behind his back, grips the truth: The central tension of this poem isn’t about steely resolve versus weakness, it’s about the conflict between an aged Ulysses’ will and his death. The voyage depicted is an exercise in abandoning his duties to Ithaca in search of evidence of spiritual realities that would point to proof of life after death. It’s about doing one last deed to escape being forgotten. The portions of the poem that Healey elided are all about endings: “Until I die”, “It may be that the gulfs will wash us down [he will be annihilated upon his death and forgotten]”, “And see the great Achilles” – who is dead. The poem points not to Ulysses’ greatness, his “heroic heart”, but to a creeping shadow of irrelevancy that must have fallen over Healey’s vision of justice. I think he saw Republican dominance of the Texas court system weakening, his lifelong concept of what “justice” meant washing out with the tide. Indeed, I think many of these men are starting to see the day coming when their actions will be seen as fundamentally evil, much in the way thinkers of our generation view concepts of justice from past eras. I wonder if Felcman ever knew that hidden within this praise was an acknowledgment that his boss was calling him a dinosaur; I wonder if both men knew that the flag waving proudly behind them was unfurling in opposition to the wind. (When Healey retired in 2018, he did so with the knowledge that my old trial judge, Clifford Vacek, was going to try to replace him on the GOP ticket. Defying all expectations, conservative Fort Bend elected the Democrat, Brian Middleton, who had run on a ticket of reforming the office. Felcman was promptly fired. My father, a lifelong Republican of the William F Buckley mold, was very pleased.)

Ever since my arrival on the Row, the men have been talking about witnessing the death penalty’s last days. Every few years, it seemed, another state abolished the penalty or moved into the column of those jurisdictions that were simply not using their statutes. My dad and I spoke of developments in case law often. Although neither one of us much loved Hillary, we both believed she would win the election and usher in a liberal SCOTUS for the first time in decades. The question was: Would I survive long enough to see this happy event? This practice became a sort of delusion over the years, especially after a failed landlord with a people-of-color-complex won the office instead. We were, I think, both conscious of the fact that we were fooling ourselves, in the same way that families might discuss non-FDA approved experimental cancer treatments when all else has failed. Comfortable lies are heavy things to carry around, and somewhere along the line we spoke of them less often. Months later, after everything had run its course, I asked my stepmother for a sort of statement on how she was feeling after having experienced the Texas criminal justice system firsthand. Before answering she paused, looking down. “I think,” she answered after a few moments’ reflection, “that all of us have PTSD”.

*****

Two days after my visit with my dad and stepmother, on the 8th of November 2017, the State of Texas executed Mexican Scooby. He was the 545th man killed in the state in the modern death penalty era. Scooby hadn’t said much to anyone during his last weeks. He’d tried to explain to me the barest outline of what he thought of as a “novel legal argument” that he’d wanted to file, something (if I understood him correctly) that essentially denied the legitimacy of the sentence handed down to him. I didn’t really know what to say. Honesty clearly was not what was needed here: My immediate thought was that King Charles I had used the same argument and that hadn’t stopped Oliver Cromwell from lopping his head off. Palliative care seemed to be called for, so I simply said that I wished him luck, and that he had the right set of attorneys to handle his situation. On that point, I wasn’t lying: Scooby had been represented by lawyers from the Mexican Consulate in Houston. This group represents all Mexican citizens on the Row, and they fight harder than most any other group of lawyers practicing in the state.

When they came to take him to his final visits at 7:50am, Rayford and I said goodbye over the run, but Scooby barely responded. Ten hours later, he was killed. Not a word was said on the local news station, and we only learned the truth later that night when a guard told us. In his final statement, Scooby again professed his innocence, saying that he “[would] not and [could] not apologize for someone else’s crime.” He then stated that he would “be back for justice”. “You can count on that,” he concluded ominously.

Amen, bro.

Polunsky is always capable of showing you new ways of experiencing desolation. You can be sitting on your bunk, a book open in your lap, your thoughts on 2-Cage that is now-empty-and-yet-not, an emptiness that seems like a reflection of other deaths, other hollowed out spaces that bear the shape of friends departed. You will take a piece of paper out of a folder and try to get this thought down, and how this cascading chain of similar-yet-distinct absences was a sure sign that one has been locked up too long, and that maybe it really was time to go. You can be weighing the right set of words, and barely register the fact that an escort team has come up the stairs, an inmate in between them. You will pause for a moment, trying to remember if someone has left the section for a visit; you will come up blank. Then you hear one of the guards scream for the picket officer to “wake the fuck up” and open 12-Cage. Oh no, you think, realizing that someone new has been given a date, another human being has suddenly become terminal.

The slit in my door faced the wrong direction to see the newcomer, but it didn’t look like they had suited up the team for him, which I found to be interesting. I had to ask Juan Castillo who they had brought in. “Damn, Thomas,” he hesitated, clearly not wanting to tell me, and my stomach did a nasty little backflip. “It’s Rosendo, bro,” he said at last. I placed my forehead against the cold steel of the door, closing my eyes, thinking that even after everything, I still only knew a few of the 11,011 faces of despair.

Rosendo, “Rod”: the man who had tried to elevate my spirits as the goon squad was hauling me off to Deathwatch – the man who I had told I would be seeing again soon. Rod, one of my best friends on the Row. Rod, the man I met the day he started cracking up after he heard me call one of our wardens “Major Major” because he got the Joseph Heller reference and the insult contained within. To this day, I cannot truly untangle the emotional ball of yarn that I felt in that moment: anger that he was now in peril, and that a nation he’d served in the Marine Corps would really try to kill him like this; sadness over the same; a tiny, quickly suffocated sense of relief that at least I would now have a friend next to me on the battlefield; and finally a great burst of anger and self-loathing for having allowed that last to have existed for even half a nanosecond. I shook my head angrily and pushed off the door, calling out to my friend.

“I think you might have taken my parting comment a tad too literally.”

“I couldn’t stand the thought of you having all of this fun without me,” he shot back. “I’m kind of disappointed they didn’t bring the shield on me. Cheated, even.”

“When is…” I started, before tripping over my diction. “Er… When is the big dance?” I finished, somewhat awkwardly.

“March 27th.”

My stomach did another ugly somersault. “Those fuckers. The day after your birthday.”

“They’d have loved to have done it on my birthday, if they could have.” I glanced at the calendar, seeing that the 26thwas a Monday, a day of the week unavailable for executions. This isn’t the first time this has happened. Prosecutors seem to enjoy playing games like this when they can.

“Damn. I don’t know what to say”, I muttered, because I truly didn’t. “Look, I’ll send a book and something to eat and drink down there in a minute. They won’t bring your stuff until the middle of the night.”

“Okay. Hier stehe ich. Ich kann nicht anders.”

That one took me a minute. “Bah”, I laughed finally, stepping back from the door. Leave it to him to find the perfect line: Although I am a nonbeliever and Rod a Catholic in good standing, we both possessed similarly negative feelings about Martin Luther, so his use of the quote was a sort of sign of solidarity, that we could still agree on many things though we came to that point from different directions. It was also a statement of who we were: Me, the gringo who spoke fluent Spanish; him, the Mexican who didn’t but who made up for it by possessing flawless German. In kites, he would often refer to me as a “white mojado”; he was a “Third Reich cholo”. Stupid, I know, but you get your laughs where you can when you are sitting on the gallows’ steps.

It took me a few minutes to get some goodies together for a care package and remove my fishing line and pole from their hiding spots. Convicts braid these lines out of cotton threads from sheets or nylon from shoe laces; the poles are layered paper, rolled very tightly until the centripetal pressures have wound the paper to the density of wood. This is the main vehicle for trading items with people in an ad-seg wing. On an average day, one will see this operation take place dozens of times. Sometime in the middle of me delivering these items, Batman injected himself into the conversation, speaking to Rod.

“Man, color me jealous,” I commented, apropos of nothing. “It took more the 72 hours for John to acknowledge my existence. You managed it in less than ten minutes,” I told my friend.

Batman made a caustic comment about how he would always vastly prefer to converse with a fellow Marine over some member of the “multi-culty brigade”, one of his many slurs for liberals. I laughed, but it did suddenly strike me as odd: Of the five men with dates, two were former Marines. Over the years, I had met two former soldiers from the Army, one ex-Navy sailor, and one man from the Coast Guard. Of the Marine Corps, however, there were at least three dozen on the Row. There’s something going on there, but I don’t know enough to begin to guess what it is. It was good to hear John trying to be social, though, so I mostly kept quiet while they engaged in their whole tough-guy-consolation thing.

“Hey,” Batman remarked a few minutes later. “Since we’re all writers, I guess the least you can say is that we will have plenty of material to write about. Like Harry Lime said, ‘bad times make for good art’.”

“Orson Welles, The Third Man,” Rod responded at once. The man was an infuriatingly precise walking encyclopedia for all matters film related. I more or less conceded those topics to him when they arose in trivia games we sometimes played against each other. “‘In Italy’,” he started quoting from memory, “‘for thirty years under the Borgias, they had warfare, terror, murder, and bloodshed, but they produced Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci, and the Renaissance. In Switzerland, they had brotherly love, they had 500 years of democracy and peace – and what did that produce? The cuckoo clock.’”

“Fuck the Swiss,” Batman responded, being Batman.

I barely remembered the movie. “Wasn’t Lime a psychopath?”

“A rather genial one, yes.”

“Maybe not the best person to go around emulating, all things considered.”

“Like it matters who we quote. We’re fucking corpses anyways”, Batman screamed.

Rod chuckled a bit over my exaggerated sigh.

Touché, John. Touché.

4 Comments

Deborah Allen

December 22, 2023 at 2:44 amI hope you don’t mind me leaving a comment. I adore your writing. It’s exquisite. You have a gift, thank you for sharing it.

Dividing by Zero – Part Two - Minutes Before Six

March 12, 2023 at 6:51 pm[…] To read Part Three click here […]

Martina Quarati

February 21, 2023 at 2:36 pmI was waiting for the next part! Thank you so much. It gives so much to think about. I’m Italian, but I oppose the death penalty with all my heart. A big hug to you all from Italy.

John

February 20, 2023 at 2:04 pmExcellent essay.

No man should be put in solitary for no good reason, with no foreseeable end date. That is evil. Frankly, worse than death. I guess that is still the case? I wish there was someone to email, or call about this. But, I fear running the risk of making things worse.

Every living human should be treated humanely. They spared his life for what? To be cruel to him for 50 years?