Foreward

This series was originally written in late-2018. It is the result of my participation in a PEN Writing for Justice Fellowship, which I won that year. I have delayed publication until now due to my continued placement in solitary confinement, thinking that some legal maneuvers I have been making might bear fruit, and I didn’t want the interference. Since this turned out not to be the case, this feels like a good time to throw caution to the wind, and maybe lob a few bombs while I’m at it. I would like to thank Caits Meissner and all of the people at PEN for their support during the writing of the early drafts, especially after the TDCJ made their disapproval apparent by disappearing all of our correspondence. I am appreciative of Maurice Chammah for his help in editing, as well as Dina Milito and Teri O’Neill for editing and formatting and all of the other thousand talents they bring to every piece published on this site. One version of this series was presented to the PEN World Voices Festival in 2019; another was read by Maurice Chammah at that year’s Life and Death in a Carceral State event. A slightly shorter version of what will be seen here as Part Six was published in Guernica magazine, and my thanks go to Ann Neumann at that publication for her assistance. All errors and other connected ignorances and stupidities are, of course, always my own.

“Begin at the beginning,” the King of Hearts advised the flustered White Rabbit in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland,“and go on until you come to the end; then stop.” I’ve always loved quotes like this. It seems such a simple, common-sensical piece of advice, the sort of remark that practically begs a response of: Well, duh. It’s only when you try to apply the King’s instruction to one’s lived experience that you begin to glimpse just how devilishly complicated it is. What introduction exists that doesn’t automatically imply something even more antecedent? How can one ever speak of first causes without at least a sneaking feeling of even more prior facts? Ever since I arrived in this alternate reality zone civilians call prison and decided that witnessing was the only moral response available to me, beginnings have proven to be something of an elusive quarry. I sit down to write, and I find myself circling my topic in ever-widening roamings, trying to locate the weak point in the barrier between our world and that of the story, the exact spot that betokens the true first word – which every writer knows is the vein that one can cut into that will take you straight to the beating heart of the tale. Quite often I end up stepping back from a heap of words, thinking: Man, that’s not right – that’s not right at all.

I wasn’t like this before I came to this place. This inclination (obsession? Here one struggles to diagnose the neuroses that prison has inscribed upon me) for peeling back the layers of the stories we tell ourselves about crime and evil in order to get a glimpse of the root of things is something that I learned in these halls. I find this to be continually surprising, though it probably shouldn’t be: Give a man a definite end point to his existence, then dump upon him hours and days and weeks and years and decades with which to contemplate his eventual demise, and he will inevitably tire of bouncing his thoughts off the uncrossable barrier of the nihil ahead and will start moving backwards in time. How did I end up in this hellhole? Where was my very first wrong step? I’ve done evil: am I evil? Eleven years I spent on Texas’ Death Row; for eleven years I probed at this topic, bugging neighbor after neighbor with questions like this. I seldom heard any answers that came close to satisfying me. Worse, I seldom heard anyone even asking the right questions.

The quest for the catalyst of evil is, to my way of thinking, the story behind the story that the media tells about death penalty cases, the hidden image painted over by brighter, more click-worthy colors. Like all palimpsests, obtaining a clear view of this world submerged beneath another is very difficult. It requires different questions, different tools, different goals. In my humble estimation, the reason that crime and violence seem so surprising, so senseless, is that we never really rewind the tape back far enough. Cut out the first one hundred pages of any book: Of course the rest of the narrative is going to leave one confused. You’re simply missing too much of the story, you aren’t beginning at the beginning.

The State prefers it this way. The law’s highest goal is not understanding but finalization, settlement. This is read by many government lawyers as a desire for parsimony, for the simplest possible answers, the straightest and least expensive line between infraction and gavel. Unlike science, where truths are always provisional and progressive, the law is a fundamentally conservative mechanism, always peering backwards into the world of stare decisis for guidance. It shouldn’t then be surprising that the idea at the foundation of America’s theory of law is a very old one. All crime is seen as the end product of a risk/reward calculation, the consequence of a will unencumbered by contextual influences. This harmonizes nicely with an autonomy myth that dominates in the United States but is weak or non-existent elsewhere in the club of developed nations: a set of beliefs, norms, and mores that hide our dependence upon each other and society. The more interdependent we grow, the less social awareness many of us seem to possess, and the more individuals flee complexity for ideological silos where their identity is easier to control. Enter stage right: Stories about bootstraps and the American mythology of hardy and courageous Horatio Alger types. When viewing the world through this lens, assigning agency is easy. The ‘why’ of crime is largely irrelevant. All that matters are the ‘who’ and the ‘what’.

If you take the King’s advice and follow the history of the American concept of personal responsibility back far enough, you will end up stepping into the world of Puritan Christianity. The primacy of the will so favored by Augustine and encoded into law by centuries of conservative jurists relying on unstated soteriological theories developed by Luther and Calvin constructs a legal person who stands in a purely negative relation to the law. It is the position of the dead, standing corem Deo in the shadow of the judgement seat, powerless, awaiting a verdict for which no appeal exists. It is supposed that on that oft-delayed day, God will not be overly interested in having a discourse over deterministic influences. Only personal, isolated guilt is thought to matter. This is an easy concept to grasp: There is no such thing as community, we are all Robinson Crusoe, and Margaret Thatcher was right when she claimed that “There is no society, only individuals.”

The opposing view to this requires one to recognize ourselves as belonging to and depending on a wider world, one composed of dizzyingly complex maps of dependence. The choices we make not only impact our lives but those of everyone else and are impacted by everyone else: In this view, “I” only exists within the matrix of a “we.” Something like this view exists in corners of Europe today, where contextual and deterministic factors are always weighed during the court process. Personal responsibility still matters, but so do poverty and drug abuse and an awful childhood and mental illness, all of which redirect pointed fingers in myriad other directions and which require changes in public policy. It is a common view in northern Europe that unless society looks out for everyone, no one can be safe. I do not think it is an accident that crime and recidivism rates in Scandinavia are microscopic when compared to our own.

As one tries on this view for fit, it begins to dawn that this ultimately means that you are responsible for everything. Sometimes this is easy to acknowledge: You probably didn’t actually need the SUV you bought, but you purchased it anyways in the face of the knowledge of the impact of emissions on a warming world; you recognize your responsibility for climate change, though you find ways to rationalize this. It gets more complicated when you consider things like the war in Iraq, the increasing use of prisons as the State’s only government subsidized mental health facilities, or the election of Trump. These things were beyond your control, you say. Maybe you spoke out; maybe you signed a petition. The fact remains that for each of these things to come to pass, history required that every last one of us behave in exactly the manner that was needed. Everything is on us. Sartre made this point in a much more eloquent way when he wrote in Existentialism Is a Humanism that “Man is responsible for everything he does.”

This can seem strange at first, overwhelming even, this taking of ownership for spirals of responsibility that seem to carry far beyond the power of any one person, any one life. I have found that it can also become empowering and liberating: In the act of assuming responsibility for the ills of the world, we commit an act of moral resistance aimed at forces that seem beyond our control. Poverty, inequality, a crumbling social safety net: We begin to see our true impact on societal issues as we make them ours; the web of dependence becomes clearer. Crime, the real roots of crime, begin to stand out. They are no longer mysterious. Indeed, crime becomes expected, a natural byproduct of a society and culture whose soil remains polluted. That’s how you begin at the beginning – that’s how you begin to see a way to writing better endings.

Unfortunately, many people in America are unwilling to entertain such a radical change in path. It’s very comforting to exist in an atomized world, to be able to assign blame and agency with little thought. Reducing levels of crime would require too many changes to the political landscape: More taxes, less religion, less lex talionis. It’s simpler to believe in only the responsibility of the individual and to espouse cynicism over the power of man to correct man, ignorant that this very disenchantment is merely irresponsibility masquerading as toughness and is creating the necessary conditions for criminality to flourish. The roots of crime therefore sink beneath the soil, and all we can focus on are the fruits. True beginnings are lost.

I know that may sound overly complex. I just don’t see how we are ever going to even begin to solve portions of the crime problem in America until we realize that a desire for simplicity is not serving us. Roughly five percent of the global population are Americans, yet twenty-five present of the world’s prisoners are found within our borders. We are not an inherently more violent people than anyone else, so this is clearly a policy issue. If these statistics don’t scream out for a need to revise our approach, I don’t know what else would.

*****

If true beginnings are beyond our current collective imagination, endings are still well within reach. Texas makes this part easy. Too easy: For those of us eking out what passes for our golden years in solitary confinement, the role of Charon is usually played jointly by the members of the Extraction Team. This is not, as it happens, a terribly difficult semiotic code to crack. They don’t want it to be: The message, inscribed in every cadenced fall of matte-black jackboot, every clash of baton on shield, is calculated to howl: We have the power; obey, acquiesce, or else.

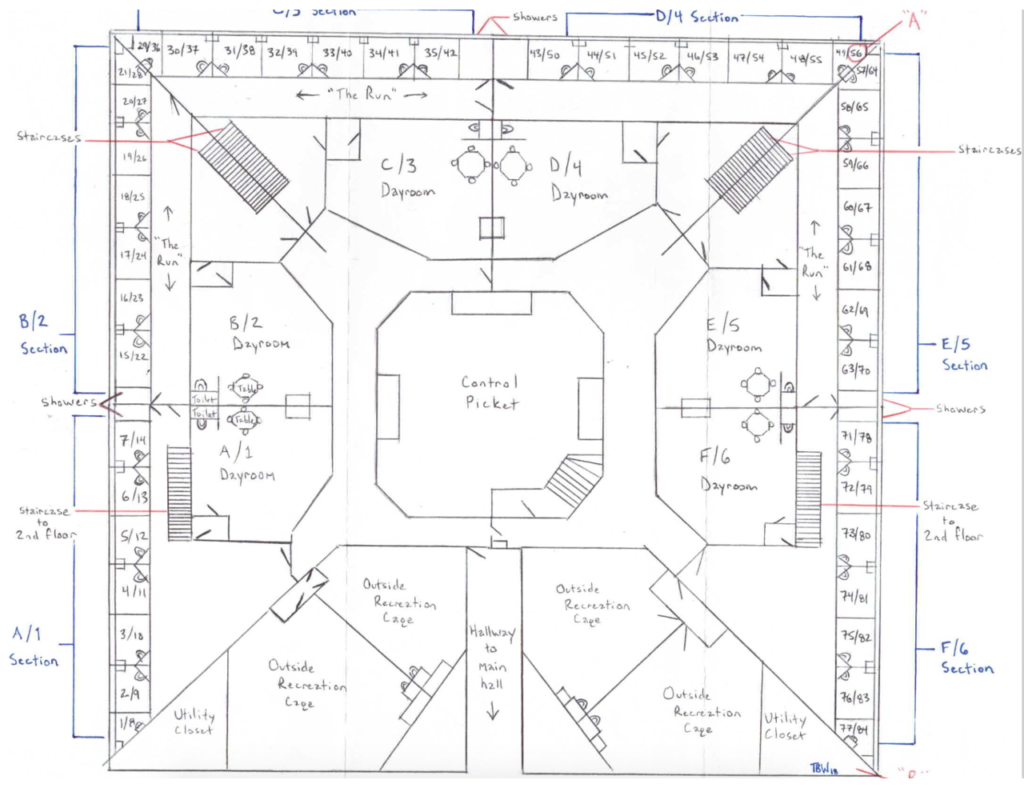

They came for me at 4:46pm on the 2nd of November, All Souls Day. My cell, B-56 (“A” in the diagram above), had an excellent view of the pod’s entrance, so the squad came at me sideways. Each of the pods on Death Row has a utility closet on the second floor (“B”), which houses the boiler. A passage connects this closet to its mirror on A-Pod, across the main hall. Wanting to minimize the amount of time I had to prepare for them, the team accessed the closet and then stormed B-Pod. The first any of us knew of their presence was when one of my comrades in 83-Cell screamed “Sneak attack!” Seconds later, a chorus of other voices joined in: “Team on Two-Row!” “Sargent V- going towards E-Section!” “Look out, y’all! Team on the way!” Dubbed over all of this was the sound of Big Will imitating a police siren, a racket whose meaning was etched deep onto my gray matter after the unfortunate years of the Shakedown Crew, when a dedicated team of ten officers spent every hour of every day trashing cells for a living. (Prison creates weird association chains: Filth abounds, so the smell of bleach has come to give me the same sort of dopamine hit that maybe citrus or vanilla once did. Every single piece of clothing possessed by prisoners in Texas is white, so that color has taken on almost purely negative feelings for me. If an angel of the Lord descended upon my cell in resplendent white robes, I’d instantly think it was playing for the other team. Big Will’s faux siren, so deeply connected to images of officers tearing apart my books and invading my personal space, creates a response almost as strong in me as someone scraping fingernails across a blackboard. You probably think I am overexagerating this, but this only really exposes how little you understand about the ways that prison rapes your mind.)

I didn’t think that the team was heading in my direction. Aside from the literary and litigational bombs I’m known to toss at the State on occasion, I am a model inmate, not generally the type of prisoner that requires the input of roughly 1500 pounds of body-armor encased redneck to ensure compliance. I therefore walked to my door mostly out of curiosity, after giving my cell a quick scan to ensure I had no contraband outside of my safe spots. B-Pod had finished with recreation and showers hours before, so it seemed odd that the administration would feel the need to go beating up on anyone within forty-five minutes of shift change. That, I recall, was my main thought as the voices changed, indicating that the team was now in E-Section: That somebody in the Major’s office had screwed up, because now a pack of officers was going to have to stay late to fill out paperwork.

That shifted once I heard the crossover door pop open from E-Section. The next morning, when I began writing notes on what were to be my final 113 days on the Row, I tried to zero in on the exact moment when I knew my death warrant had been signed: I could hear Shooter’s voice clearly when he yelled that the team was about to enter D-Section. That can’t be right, I thought, nobody’s done shit over here. Then the lock clicked and I knew they were coming across. This meant that the target of the team had to be one of the seven men living on Two-Row, because A-C sections had been cleared the week before so they could put some G5 inmates on that half of the pod (“G5” is a custody level used in population for maximum security inmates). That’s when the first tendrils of the thought crept into my head that if they weren’t coming for a disciplinary extraction it might be for an administrative one. As soon as Officer H- pushed the door open, his eyes clicked over to me and I knew I was a dead man.

Since I was in a corner cell, the team had to stomp past my door and then swing back around to let the tail clear the staircase. Under other circumstances, this awkward maneuver might have looked comical; for the briefest of seconds I thought I might have been wrong and they were headed for someone else, schadenfreude being an embarrassingly familiar companion in a place that butchers people on a monthly basis. Then Officer O- came through the crossover door holding a camera. She pointed this directly at me and did not deviate. Next to her glaciating gaze, the dead fish’s eye of the camera lens seemed warm.

Sergeant V- swiftly positioned himself in front of my door and removed a pair of handcuffs from his belt. He looked behind him once to ensure that the disciplinary conga line had righted itself and was now prepared. The breastplate of the first goon – “One-man” in the patois – was surprisingly intricate. It had all of these interlocking plastic scales that coruscated outward from a circle positioned directly over the solar plexus. The men all looked like giant beetles, their faces hidden behind polarizing masks. I’d never had the team directed at me like this, so I’d never really appreciated the fact that someone makes all of these accoutrements of war, that this is a business for someone. It still fills me with a sense of despair when I consider that there are actually human beings who sit around a table going: “You know what this world needs? Paintballs filled with tear gas!” (Then, in this scenario, where all of the principle actors look exactly like the late Antonin Scalia, oddly, someone else would slam his – of course it should be a “he”, right? – palm down and exclaim: “Even better! How about a Plexiglas shield that has an electric current running through the front, so when you ram someone, they get tased?!” An overactive imagination is yet another present a decade in solitary confinement has gift-wrapped for me, it would seem.) I’d heard the term “prison-industrial complex” before, but it was pretty much just a theoretical concept for me until that moment.

Normally, when the handheld cameras come out to play, guards start to speak in a sort of wannabe-militarese that always makes me question whether the speaker actually fully comprehends the particular diction they are required to use. Lots of “Offender So-and-Sos” and “henceforths” get deployed; chemical weapons are always “utilized”, never merely “shot into your dumbass face”, though such wording is pretty much always included subtextually. I once heard an officer confuse “substantially” for “subsequently”, and I would have laughed, except then I’m pretty sure I’d have gotten the gas along with my neighbor. Sergeant V- wasn’t having any of that, however. He simply told me that the Major wanted to see me. There wasn’t much doubt left at that point. High ranking officials in the Texas Department of Criminal Justice (TDCJ) practically build moats around their offices in order to minimize contact with offenders; if one actually wanted to speak with you, it meant you were in serious trouble, someone in your family had died, or, lastly, that you were about to.

*****

It wasn’t that I was completely ignorant of the possibility that my death warrant could have been signed at any moment. In Texas, the appellate process generally flows in only one direction. The velocity is determined by a number of factors, all political. Are one’s District Attorney’s office and county judgeships dominated by Republican officials? If so, the process is invariably more rapid. If one comes from a county controlled by Democrats, one can count on the process at the county level moving at a slower pace with increased options for genuine review. Was one’s federal district judge nominated by a Republican or Democrat president? If the former, expect a more rapid federal process, more use of procedural bars. One learns to gauge the estimated time that one is likely to spend at each appellate waypoint based on cases with similar factual findings and county political make-ups. I knew that the US Supreme Court had declined to review my case on the 10th of October. There are so many factors that influence the final act of a death penalty appeal, however, that one never really knows exactly when the order will come down. Some people receive execution dates almost immediately; my friend Arnold Prieto Jr. waited almost seven years before his warrant was finalized. (Seven years! Imagine for a second what that must have been like for him, waiting each day, wondering if that would be the morning that some politician would decide that your life had run its course. I have no idea how he stayed sane.) The overwhelming determining factors for the duration of this delay are, again, mostly political in nature: The more officials involved in your case aligned with the GOP, the fewer your final appellate options are going to be and the shorter your wait for execution.

The State is always the first mover in setting an execution date, but exactly who does the moving and at what speed varies from state to state. In a number of jurisdictions, such as Arkansas, Florida, and Pennsylvania, it is the Governor that issues the death warrant. In Alabama, Mississippi, and Ohio, that responsibility rests with the state’s Supreme Court. In North Carolina, the state’s Attorney General controls the process; while in Oklahoma, it is the state’s Court of Criminal Appeals. In Texas, along with fifteen other states including California, Louisiana, and Colorado, it is the trial court judge that signs the order. Generally speaking, however, it is really the District Attorney that sets the pace on these matters, given the political capital such figures regularly accrue in conservative Texas from executions. Before a judicial killing can be scheduled, the District Attorney’s office confers with a representative of the Texas Attorney General’s Office in order to agree on a specific date on the calendar. There was a time in the not-so-distant past when such a calendar didn’t exist. In practice, this meant that Texas occasionally ended up with multiple executions scheduled on the same day. It was determined that this imposed a heavy psychological, as well as logistical, burden on the staff at the Walls Unit – where all executions in Texas are carried out – so officials ceased this practice after the double execution of August 2000, if memory serves. (There is no outsourcing of memory to Google in prison, so all facts and figures included in this series are based off of my recollection, unless otherwise cited. All information can be checked for accuracy by perusing sites like the Death Penalty Information Center.) In reality, someone in the Attorney General’s office figured out that if they scheduled more than four executions per month, it vastly increased the number of critical media stories about the State’s practices nationally. I have no idea why the number four should be the threshold, and not three or five, but this is a trackable statistic. Since then, the State tends to shy away from multiple killings in the same week, though this does still occur on occasion. Once a date has been agreed upon, the District Attorney requests a hearing in front of the trial judge, where a motion for the “finalization of the sentence” is ruled upon. Sometimes the condemned is allowed to be present for this event. This was not the case for me, a point I’m actually thankful for. These hearings are little better than an opportunity to parade the condemned in front of the local media one last time, an experience that I’d already been through enough for one lifetime.

There had been some degree of hope in my camp that we could persuade my trial judge to hold off on the motion to set my date. My original trial judge, Clifford Vacek, retired unexpectedly a number of years after my conviction, not long after getting re-elected. He claimed that he had a “couple of young cow dogs that need[ed] training”. (This was not a joke – at least I don’t think it was. Are there really cow dogs?) This seemed like a pretty slick move on his part. By retiring after the election, this allowed then-Governor Perry a chance to appoint a successor for the remainder of Vacek’s term, a successor that might not have won an election had she been forced to run. Essentially, this was an easy, backdoor method of conferring incumbent status on a candidate without them having to earn it. It’s really quite an elegant solution, so long as things like democracy don’t matter to you.

In this case, I initially didn’t mind the hijinks terribly. During one of my pre-trial hearings, my trial attorney told me about a photograph of an old oak tree hanging in the foyer outside my judge’s office. I remarked that this seemed tasteful to me. My attorney smirked, obviously relishing my naiveté (which says, I think, quite a bit about the type of man he was), before going on to explain that this was actually a depiction of the old hanging tree that once stood in the park area outside the old courthouse. Most of the counties in the South had just such a tree. As late as the 1890’s, almost nine out of ten executions were performed by local authorities; by the heyday of the Progressive Era, almost eight out of ten killings were handled instead by centralized State officials, a shift that resulted from a growing sense that public executions brought out the worst in the populace. This is perhaps best evidenced by the crowd of roughly 20,000 Kentuckians that turned out to witness the very last such killing in 1936, the members of which spent their time eating hot-dogs, popcorn, and getting drunk. I honestly have no idea if my attorney was telling the truth about this photograph, or if this was just another of the many falsehoods he served up to me. If true – if this was in fact the message that Judge Vacek chose to broadcast onto those he served judgement upon – then I figured that pretty much any other human being on the planet would be preferred when adjudicating my last minute appeals.

Vacek’s replacement, Maggie Jaramillo, seemed more human. She was Hispanic for starters, and obviously not laboring under the weight of a Y-chromosome. Even better: she actually had defense bar experience, a real rarity in Texan judges. Better than better: she’d been a delegate at the Precinct 1076 convention for Hillary Clinton in 2008 (though she would later claim that she’d always voted in the Republican primary, despite records proving otherwise; either she already had a politician’s loose connection to the truth or her memory was more than a bit spotty, neither of which, I note, are particularly good traits in a judge). Best: she’d actually tried a case with a lawyer employed by the firm handling my federal appeals that had some similar facts to my own. In that case, she’d managed to secure for her client a very favorable deal – certainly something far more favorable than the death penalty. Given all of this, my lawyer thought that she might be able to resist the calls from the District Arrorney for the setting of a rapid execution date. Not so much: my hearing lasted less than five minutes, just long enough for Judge Jaramillo to sign off on the death warrant. I guess she really was a Republican at heart.

Here is a copy of the death warrant and other related paperwork, proving, I suppose, that nobody can be executed in this country without first decimating a small forest.

*****

Sometimes it can take a week or two for the trial court to send all of the necessary paperwork to the TDCJ. In these lucky cases, the prisoner is made aware of his peril either from friends, family, attorneys, or the media, rather than via the goon squad. They wasted no time in my case: Less than a day had passed since the warrant had been issued before I was being removed from my cell. The section was quiet as I was escorted down the stairs. I’d seen men carted off like this for eleven years, so I knew the runs would explode into a grinning orgasm of gossip and rumor as soon as I was out the door. Not for the first time – and certainly not for the last – I remember thinking that I was not going to miss any part of the Polunsky Palace when they killed me.

I did have at least one genuine friend on B-Pod. When I passed by F-Section, Rosendo “Rod” Rodriguez III shouted out for me to keep my head up. This was meant as a sort of dark joke. Words don’t seem to have much power in the face of calculated cruelty or institutional indifference, a point the pair of us had discussed on numerous occasions as we ineffectually attempted to cut through the trite clichés of condolence that normally come to mind at such times. You want so badly to do something when a friend’s life is threatened, but there’s simply no action available, save seemingly empty assurances of solidarity. I was not in the right headspace for snappy rejoinders, so I simply nodded in his direction and told him I’d see him soon. What I meant was that eventually we would have our visits sync up so that we could talk to each other in the visitation room, but these words would shortly take on a much grimmer meaning. There is no way to quantify just how much I would come to regret saying them over the months to come.

It was a regular shindig in the Major’s office. Several secretaries took one look at my retinue and swiftly decamped to a back office, from which a small aviary of telephones could be heard trilling. I’d never actually been inside of this space before, but I’d glanced within hundreds of times over the years on the way back from the visitation room.

It was, as so many things are in the TDCJ, shabbier up close. The (no doubt) inmate designed, manufactured, and installed wood paneling might have once looked decent, but after a few decades of wear and tear it appeared to be well along the process of coming to terms with the Second Law of Thermodynamics. The carpet was moppable – which I think says all that can or needs to be said about it. The furniture was either handmade in the prison craft shop or looked to be Korean War era Department of Defense castoffs, all except for the couch. My gods: the couch. I stumble over my adjectives when attempting to convey to you the swirling vortex of horridness that was this couch. Does the Pantone Color Matching System possess a shade approximating what you’d get if you mixed lung tar and baby excrement into a single, putrid slurry? If so, that’s about as close as I can get to describing this color, heretofore unknown to science. I have no idea what the material was – no idea. Fake-fake-pleather? Some petrochemical industry abortion unfit for market consumption? Human skin? I would believe anything. There were weird, Fautrier-esque squiggle-spots embedded in this substance that I originally thought were stains but then quickly realized had (maybe?) been printed upon it. Several gashes were sealed with silver duct tape, which had the curious effect of actually improving the sofa’s appearance. It looked like the thing had escaped from a maximum security prison for criminally insane furnishings. I’d have sooner sat on a live shark. Naturally, the cushions were occupied by two officers who apparently didn’t share my sense of aesthetics. I wondered idly what everyone else would do if the couch decided to eat them, and if I would somehow catch the blame for this.

The only item even remotely new was the huge flat screen monitor affixed to the wall. The small crowd of officials gathered to wait for my arrival had obviously found something humorous in the dozen or so windows displaying surveillance footage on the screen, because they were grinning widely as the Captain picked up his walkie-talkie and informed someone that they needed to check out “Delta-63.” I was made to wait in the doorway as this inspection was taking place. Activity sloshed around behind me. Swiveling about, I noticed that the Extraction Team was still shadowing me. Three of the five members had crammed themselves into the common space adjacent to the Major’s office; thankfully, they had left the electro-shield out in the hallway, or things might have turned out to be quite a bit more exciting. Security is essentially the art of making nothing happen, and I guess they were taking no chances with me. Still, it seemed like overkill. It’s hard to describe the psychic weight of what it’s like to live in a world where that which is not absolutely compulsory is absolutely forbidden, the way normal thought processes and behaviors are informed and deformed by this gravity. It’s just too alien an experience for anyone who has never been incarcerated to fully grasp.

As I watched the War Beetles watch me, Officer O- continued to flit about with her camera, a look of hopeful expectation in her eyes. I’d never actually been this close to her before. Alone amongst the women working 12-Building, Ms O- wore heavy layers of make-up. Her hair was always done up as if she were about to go out on the town, and she flirted dangerously with the line on the appropriate amount of jewelry she could wear on the job. Almost from her first week of training, it was decided by all of the high ranking officials (all men again) that she was too haughty (not to mention cute, though I’m sure that had no bearing on the matter…) to work the pods, so they assigned her to work 12-Control and the Major’s office. Over the course of several years, she had spawned a nearly unending river of rumors and had acquired the nearly official title of Major’s Lapdog. If dog she was, she was the type of pooch that only rich people would own – a borzoi hound, or something. I always thought she looked exactly like someone Giovanni Boldini would have painted.

Turning slightly away from the lens, I counted over a dozen officers in my immediate vicinity, and wondered about the kind of idiot that would choose that sort of scenario – hands secured behind the back, no less – to engage in fisticuffs.

These are the moments that sandblast the soul. I’ve never had much success explaining to Freeworlders how one slowly becomes vaccinated against the violence one witnesses in the prison world; as bad as it gets, one builds up a sort of antibody response to even the most egregious cruelty of the staff. I have never, however, found any way to defend against instances of outright absurdity and the way these tend to cleave your mind into two halves: One wanting to laugh, the other to cry. I’d never once injured a human being during my thirteen plus years behind bars; never once allowed my hand to touch a weapon of any kind, or contraband cell phone, or any of the various narcotics that flood our prisons. There was no need to have three brutes breathing down my neck, no reason for the camera, the Grand Guiqnol-esque spectacle of me waiting in the doorway for some sort of punchline to arrive from Delta-63. No reason, that is, save for the fact that some bureaucrat had decided long ago that notification of a signed death warrant required an overwhelming show of force. I don’t know why. I guess it looks tough on paper. In any case, I’d made thousands upon thousands of ethical, correct choices over the years on the way to becoming the sort of convict that any prison system ought to have been proud of, and yet none of this seemed to matter in the tiniest way. I felt drained, enervated. I wanted to shrink away and find some dark place to be alone where I could lick my figurative wounds, but these people needed their moment. It hurt in a way my words fail me to describe.

When the response eventually came over the walkie-talkie – curses, naturally – the room erupted in laughter. That anyone could pivot from such merriment to the notification of my impeding murder is difficult to imagine – and yet the years spent awaiting execution are built of such moments. More than a few men have walked to their deaths happy to be done with the whole business, and I believe it has far more to do with experiences such as this than with grander, more noticeable events.

Eventually the Major pretended to notice me. I’d never spoken to him before. The previous Major had been fired over a sex-scandal – he’d told his wife that he was going to stay in officers’ quarters for a few days to be able to work a string of overtime shifts, when in actuality he’d been on a cruise with a subordinate – and his replacement seemed to have been selected on the theory that no woman in her right mind would willingly decide to co-exist in the same room as him, let alone go to bed with him. Behind his back, the staff called him Shrek, though I always thought that was a stretch, beginning with the fact that the Major’s dominate skin tone was a deep orange, not green. If anything, he looked more like Jabba the Hutt. I suppose that would make Ms O- that little gremlin-looking creature that always laughed inappropriately whenever something awful happened to anyone. I have no idea who Leia would be. I wouldn’t care to see any of the officers at Polunsky in a bikini, metal or otherwise.

“You got you a date,” Jabba said at last, reclining in his chair. There didn’t seem to be any appropriate response to that, so I applied a heavy dose of that good old conversational solvent, silence. After so many years living in proximity to the reactor cores of faux-justice, words can start to feel meaningless, just another set of tools corrupted by bureaucrat-lawyers. Sometimes one wishes just to remain mute forever. The screws seemed to be waiting for some sort of response, maybe a nice bit of wailing and gnashing of teeth, which only strengthened my resolve to remain silent. Uncomfortable for the first time, the Major finally added: “On February 23rd, 6:00pm.”

I thought about that for a moment, doing the math. “I’m pretty sure that’s a Friday,” I said at last. Texas doesn’t kill people on Mondays or Fridays, something everyone in the room knew well. One of the lieutenants sitting on a wooden bench against the wall reached for a sheet of paper on the desk, scanned it for a few seconds, then corrected his superior.

“It’s the 22nd, boss.”

“You got you a date on the 22nd of February.”

This whole scene was making me feel like an idiot. There had to be questions that I needed answers to, but I couldn’t seem to think of any of them. I felt like a particularly dim Interlocutor in a Socratic dialogue. Finally, the machinery upstairs clicked into gear.

“When will I get my property?”

“We have seventy-two hours to inventory it and get it to you,” the Major responded, his attention already starting to drift.

“Seventy-two hours from now will be Sunday afternoon,” I responded. When nobody said anything to this I continued. “The Property Officer doesn’t work weekends.”

There’s a look you get from officers when you have the temerity to quote policy (or reality) to them and expect a positive reaction. No matter how logical or correct your statement, it’s as if a second head has begun to sprout from your shoulder, or something. I don’t know why I even bother: In the TDCJ, policy always boils down to being whatever they say it is.

“We’ll get you your stuff when we can.” I knew that was bureaucratese for “fuck off, you”, so there didn’t really seem to be any point in saying anything else. As I turned to leave, Sergeant V- removed his walkie-talkie from his belt.

“We got a ‘zero’ heading to Alpha-10, clear the halls.”

There are no televisions on Texas Death Row. Our only exposure to the broader world comes via newspapers that we purchase or the Chinese knock-off clock radios the State sells on the commissary list. There exists a relatively minor circuit board hack to these radios that allows one to listen in on the walkie-talkie traffic between staff; the chatter tends to override a local pop station, one form of inanity sandwiched atop another on the spectrum. Occasionally I would flip over and listen to the goings-on out in the general population or the main hallway of 12-Building, so I’d heard about “zeros” and their movements before. When I asked my first neighbor, Robert “Big Blake” Hudson, about this back in 2007, he said that this code referred to the guys on Deathwatch, the men with execution dates. This instantly offended me.

“That’s kind of messed up,” I fumed. “Calling them that. I mean, yeah, we’re all here to be reduced to nothing, but it seems like they are going out of their way to put it in our faces.”

“Nah, little bro,” he responded through the vent. “You giving them too much credit. They ‘zeros’ cuz the old form the laws used to log they activities was called the ‘zero-four’. Somehow they just cut that down over the years. They probably ain’t even thought about that other shit.”

I knew better. Blake had been in the system for a while and was usually right about most things, but this was human nature at work: Before killing someone, it helps if you can convert him or her into an “it”. It helps even more if you can make “it” a “nothing”. It’s easy enough for the judges and politicians to dispense death and hide behind platitudinous rot about “duty” and “the greater good”. For those tasked with the actual wet work, however, strategies are required. About a year after that conversation, Robert Hudson became a “zero”; three months later, on the 20th of November 2008, the State converted label to fact.

*****

Polunsky Unit’s 12-Building is one of the most secure facilities in the TDCJ, a super-seg unit entombed within the fences of a maximum-security prison. Mother Jones once ranked it as the second worst prison in the United States in which to do time, behind only ADX Florence, the Federal Government’s official black hole for terrorists. I’ve reason to suspect that this rating had more to do with making a political statement about Texas politics than with any genuine understanding of empirical conditions, but it really is a particularly poorly managed facility. 12-Building is itself divided up into six pods, each of which contains 84 cells, and is laid out as in the diagram above. A-Pod is unofficially referred to as the “show pod”. Whenever a high ranking official, politician, or tour group from another state prison system comes to inspect Texas’s death machine, A-Pod is where they bring them. (Once upon a time, someone had the incredibly injudicious idea of allowing tours from the general public to parade about, seeing all of the condemned in their natural habitats. These ended after someone connected to a murder victim showed up to taunt the man convicted of the death.) Consequently, A-Pod is the part of the facility most likely to be given the occasional Potemkin Village spruce-up: A touch of fresh paint here, a bit of regular maintenance there. Of my eleven years on the Row, I spent 41.6 percent of my time on A-Pod. (For the interested, here are the other totals: 21.2 percent on B, 25.8 percent on C, 6.8 percent on D, and 4.5 percent on F; E-Pod has been used exclusively for ad-seg offenders since 2005, a distinction which D-Pod mirrored in 2010). If I had a home in that wretched place, it was most assuredly to be found on A-Pod.

I’d never lived in A-Section of A-Pod before, though (the first fourteen cells immediately to one’s left when one enters the pod – also referred to as “Deathwatch”). Nobody wants to live on Deathwatch. Such is the fear that this section engenders that many prisoners won’t even look in that direction when being escorted to visitation or recreation. It’s the final waypoint on a long, strange journey, the location where the rational can no longer pretend that a deus ex machina is imminent.

It was quiet when I arrived. I saw a few faces at their doors as I entered the section and was taken upstairs to Two-Row. The team finally peeled off once the door closed behind me. My cuffs were removed and the tray slot sealed. Only then did one of my neighbors, Juan Castillo, say hello. We spoke for a few minutes, and then he left me to my thoughts.

Metal bed, metal sink/toilet combo, metal door. Bare concrete walls and a narrow window that does not open. Nothing you could tie a rope to. When Charles Dickens visited Eastern State Penitentiary, that’s one of the descriptions he included in Chapter VII of American Notes: That no hooks existed on the walls for hanging clothes up to dry, because “when they had hooks [the inmates] would hang themselves.”

The cells on Deathwatch are exactly like those found in every other section, save for the addition of a camera inside the cell. It was a sleek little device that fit perfectly into the corner of the cell right above the door, made by the Bosch Company. I’d owned a Bosch dishwasher once upon a time, and for some reason this corporate presence felt treasonous; those bloody Germans ought to have stayed in the kitchen and out of my cell, I groused. I was immediately surprised at how intrusive that lens felt: I’d theorized that I would get accustomed to it over time, but I never did.

After spending half an hour thoroughly searching the cell for any contraband that might have been left behind by a previous occupant, I laid down on the metal bunk.

All of the condemned arrive on the Row battered and bruised after the ordeal of a capital murder trial. Most aren’t angry, they’re in a state of shock. Nearly everyone makes certain resolutions with themselves or their god(s) about needed behavioral changes, and many actually fulfill these. One of mine dealt with lies. Initially I thought this meant that I needed to stop telling them, but this slowly morphed into a realization that what I really needed was to stop believing in untruths – that the entire architecture of my belief system was founded on illusions. This spawned a creeping quest for a scientific rationalism and a weapons-grade skepticism that made the process used by most peer-reviewed journals look tame by comparison. I am convinced that whatever rehabilitation I have managed to obtain for myself is a direct result of the removal of a huge amount of lies that I dispensed with over the years. I also knew, however, that the months ahead were going to have teeth, and many of these same delusions were pretty much all a man has left by the time he ends up on Deathwatch. This was going to be a trial, a test of whether I truly did believe in the things I claimed, if I was anywhere nearly as strong as I pretended to be. I did have a secret weapon, though, one that I had been nurturing for many years: One has to value oneself before one can really feel fear. A healthy, positive sense of self-regard is definitely one affliction that prison has cured me of. This feeling of not being worth very much in the final analysis would prove a great boon to me over the weeks ahead.

A prior occupant had written the word “mezuzah” all over the room. I fell asleep wondering what exactly that meant.

A little past midnight a sergeant woke me up to sign for my property. According to her, the night shift Captain had told her to wait until Monday to inventory everything, but she’d been bored and admitted to wanting to snoop. I didn’t really care, as her nosiness prevented me from having to sleep on sheet metal all weekend. Also, I’d known this officer for years and I knew she was one of the rare ones who actually still possessed a human heart, and I suspected that her claim was really just a cover for her desire to do the right thing. It took me an hour to unpack my belongings and get my new cell in order.

I found myself unable to return to bed. Standing up on the bunk, I peered out the window. A-Section looks out on a wall, the back of F-Section on C-Pod. The space was entirely gray and bathed in light. All nights here are nights without stars. Stadium lights stand careful watch over the whole facility, supported by thousands upon thousands of fixtures attached to walls, fences, and posts.

Sometimes you can make out the moon, but the stars are completely lost in the haze. You have to imagine them: The moon at perigee; Mercury just a few degrees west of the Sun; Venus, Mars, and Jupiter in Libra; Uranus in Pisces. I say you “have” to do this, and I mean this in the sense of a commandment. Some of my friends on the Row think it is strange the way I try to imagine things I will never have direct contact with again: the feel of sand under one’s toes, the breeze on one’s face, the gaze of another not overlaid with suspicion or distaste. They think it is masochistic. I think they are doing a great deal of psychic damage to themselves by choosing to exist only in the carceral world. Who would want to live in a universe without stars? What would that do to a mind?Just before taking my typewriter out to begin composing some difficult letters, I removed my contraband black marker from one of my hidden arks and wrote a line from Canto III of Dante’s Inferno over the door: Lasciate ogni speranza, voi ch’entrate: Abandon hope, all ye who enter here. It seemed fitting. Dante constructed his version of Hell out of materials from our world. As Schopenhauer noted and all Texas prisoners can affirm, he still managed to make a very proper hell out of it.

3 Comments

Dividing by Zero – Part Two - Minutes Before Six

March 12, 2023 at 6:48 pm[…] To read Part One click here […]

TJ

April 4, 2022 at 10:49 amMessage from the Peanut Gallery: It’s an old friend from SF! It’s been a number of years since I’ve written – a lot has changed, but I never gave up reading your work. It’s why I wrote to you in the first place so long ago. Bart, this is one of the best things you’ve written so far – it’s very compelling. You are killing me with this – I’ve been waiting for this story since Feb 22, 2018! So when can we expect the next part(s)? I have more to say/ask but I want to wait until the story is complete. Be well

Dina

February 27, 2022 at 9:21 amThis message is from Thomas: To “Sof”: thank you for the book! In response to your message, I’m game if you are.