By: Terry Daniel McDonald

To read part one click here

By the first week of April 2010, I was in a cell with a concrete floor riven by what looked like a chaotic ley–line. Pits and chipped stone lined the edges, rising to walls with etchings, smoke stains, and smashed egg–like splayings of peeling paint. Water stains and smeared hand–prints marred the steel. White crust ringed the inside of the toilet.

My meager property was in a red chain-bag on the bunk. A thin and lumpy blue mattress was folded like a clam, pushed to the side. Sheets and my jumper were on top. It was a sad display atop the metal frame more gray than white, with edges abraded down to bare iron. I was living on the generosity of others, and accrued debt. I didn’t even have a fan. TDC was making it difficult to replace the ID card they refused to return, so I couldn’t access my account. Thankfully it was still spring, with semi-cool temps, but I knew that tease heralded the blistering heat of a Texas Summer.

Wearing boxers and State shoes, I paced like I was leaning into a storm, gritting my teeth against knee-pain, trying to understand why I found it so hard to fit in. Three steps forward, three steps back. Or I’d stop before the steel mirror with its deep patchwork of scars, watching my face fly apart into planed shards that mimicked how I felt inside.

Who did I want to be?

That was a question evolving out of my circumstances. But the question ran deeper: Who was I? I should’ve been able to figure that out while free, yes? Evidently not. I had thwarted each chance at success, continuously bashing myself against jagged rocks, until all that remained was the flotsam of my existence drifting into a prison of my creation.

Cleaning other cells had begun to reveal the disparate pieces of my fractured life, but how to repair it remained elusive.

There was a lot of work to do. The first phase was acceptance, seeing everything for what it was. But as soon as I opened myself to that task, I became overwhelmed with reality.

In most ways, simple labels defined my existence. I was alone, 29 years old and in prison. The Prosecutor called me “evil.” A Court convicted me: Society considered me a liar, thief, and a murderer. A man whose actions had been, in their estimation, on par with impulsive, juvenile conduct. Were they right? Had my manic depressive states reduced me to nothing more than a functional child? And if so, why?

I was (and still am) a son. Not a good one, mind you, but my mother and father were still alive. Mom was reticent about dealing with me, though. Dad was in his own world. I was also a grandson, a brother. A friend? A lover? I failed so many.

Those and other thoughts rattled around like loose marbles in my brain.

Riotous noise existed outside my cell, and in my vent as two pipes-chase neighbors cussed each other out. The fight was over a stamp, or a shot of coffee that cost a stamp. With the flowery, though uninspired, discourse on the myriad ways each might eat or suck genital parts, I doubted the matter would be resolved.

Then I swear a roach ran by, flipping me off in passing. I glared, disgusted, it was too fast to catch. A dust-bunny rolled my way as the roach slipped from view under the sink.

Someone in the dayroom shouted, “Cain got another one!”

My mind automatically conjured images of a piss or shit soaked victim. My black ringed blood-shot eyes flitted to the door-to the floor where a line of ants had established a “do not cross” picket line.

“Are you hurt?!” Cain’s cackling query made me cringe. “You stupid bitch, how does my shit taste?!”

Horribly I was sure. Smelling it was bad enough. I might no longer live among the bodily—fluid triad, but I was only a section away. The constant exposure made me feel like I could confidently describe each mixture by scent alone: Shit a la corn; sweet and sour, soupy excrement with beans; chunky spinach-striated turds. Please shut up!

Where was a vacation travel—planner when I needed one? My level 2 status allowed me to be moved around to the 1-2-3 section side of the pod, which would provide separation and welcome change, but cell assignment was erratic. All I knew was that I would be moved in a week.

Until then, being on 1-row in 5-section would terrorize me. It was more than the dirty cell I would soon clean. It was more than the cloud beneath my bunk — the dense webbing of a spider colony I was leery to attack. I did not like spiders. They would have to go. But I couldn’t achieve anything just then. Not with a splitting headache brought on by a racing, unstable and tense, sleep-deprived mind.

I simply began pacing again in my cramped universe, reminiscent of Robert Frost’s “The Bear”:

“Man acts more like a poor bear in a cageThat all day fights a nervous inner rage,

His mood rejecting all his mind suggests.

He paces back and forth and never rests…”

“Are you hurt?!”

Fuck you, Cain.

* * *

Who truly desires to live in a prison? Come on, who really plans their life around being boxed in and treated like a lab project? Maybe gang members? As a pit stop to gain a notch on their belt of “street cred”? Surely the homeless would prefer the uncertainty of freedom? Or would they prefer a regimented existence where clothes, showers, and three basic meals are provided?

Wait…basic is being generous!

No, I can’t imagine a person establishing a list of goals, listing “go to prison” as a major life achievement. I certainly do not want to be here. My life did not include the street life, hustling dope. Or embracing crime to climb out of socioeconomic despair. But I had despaired all the same, and prison was my punishment for being naïve to the harsh realities of life. For being bipolar and not knowing how to control my distorted view of the world.

I wasn’t perfect, ever. Growing up, if a person slighted me, I would steal from them as an act of petty revenge. I felt it just, as a matter of principle. But I was a horrible thief and my lies were totally transparent. I might as well have had a neon sign on my forehead, blinking out: “I did it!”

Living in a divided family compiled tension, frustration, and anger until I would commit other petty crimes to draw attention. Every time I stole from a store, started a random fire, acted on other crazy impulses like searching through everything in a house or playing with my Dad’s gun, the sign blazed “Pay attention to me!”

Then we moved a lot. Each new house amounted to starting over. That was not an adventure to me. I carried the weight of change as a horrible loss. The burden of being the “new kid” in a school that was either far ahead curriculum-wise, or way behind, led to the walls I erected for self-preservation. Why get close to those I would be forced to leave? Why take the time to make friends that I would lose?

It would be easy to sit here and list all my mistakes and problems. But then you’d likely think I was making excuses, yes? Or trying to justify every wrong act? Definitely not my intention. In 2010, I was at the beginning stage of mapping the web of my life. It was much like that cloudy spider-abode beneath my bunk. But I couldn’t use brute force. There was a delicate, rubix-like maze to consider, defined by the walls of a mental prison I had long thought was a shelter.

To identify the mental prison also meant I could explore the contrast of a physical one. How similar they, in fact, could be.

When I was in the El Paso, Texas County jail – the “Annex,” with its pale to gray, blocky configuration of pods — an older Mexican guy told me, “It’s easier in here.”

We were seated at a table, a chess board between us. Other men, who mostly congregated around the TV, wore our standard attire: clownish orange and white striped jumpers.

“What do you mean?” I asked, curious. I wanted to focus on the game, I even leaned forward to consider a possible move — going slow like he always encouraged me to do — but his comment made it hard to concentrate.

He moved a pawn, and then rested an arm on the table. Old tattoos spiraled to the elbow. “In here I can rest.” His eyes squinted, forming a tiny, rippling tide of wrinkles. “They give me a bed, meals, clothes. I might work, but only if I really want. I don’t have to pay bills.”

That was an argument I never thought to hear.

His eyes seemed to clear; noticing my lack of interest in continuing the game, he shrugged and added: “Every time I get out they tell me I have to get a place to stay. Have to get a job. Getting transportation and everything else is hard. Just working to make it…”

“Don’t you have anyone?”

He paused briefly, and then quietly said, “I did, but not anymore. For me it is easier in here. Your move.”

* * *

“I shall be telling this with a sigh

Somewhere ages and ages hence:

Two roads diverged in a wood, and I –

I took the one less traveled by,

And that made all the difference.”— Robert Frost, excerpt from “The Road Not Taken.”

Three steps forward, three steps back.

Pacing in a cell is on par with walking through life without direction. In wide open spaces, mental walls are delusional representations of fears, inner-weakness. Once sheltering distractions are stripped away, an oppressive weight builds in the mind. Feeling alone, then, is a partial byproduct of “needing space” away from perceived affliction.

My loneliness was never a true reality, because I was always surrounded by loving family. But the shell of how I valued authority, viewing it as necessary to an ordered life, fractured and fell away when I was abused as a child. I felt like a failure, culpable, and figured it was best to withdraw into my sadness – to hide it. Feeling much like Ethan Hawke when he told GQ, “I don’t know if you feel the same way, but when you’re depressed, it’s really easy to see everything that is fake about other people and life….” It was also easy for me to assume I knew a better way to live, never imagining adverse consequences.

A favorite song of mine is “Here I go again” by Whitesnake. Perhaps you know it? “Here I go again on my own, going down the only road I’ve ever known…” Those lyrics whisper to my innate desire to be free, beyond the shackles of abusive authority. But they also highlight how narrow and faulty my logic could be. The only road I kept choosing seemed to hide the pain, but my actions begged for help in dealing with it.

Confinement in Administrative Segregation was but my latest plea, which shined a spotlight of dark irony on my former chess-partner’s “it is easier” comment. Of course it was (and is) easier without a cell-mate, but quite hard to acclimate to and accept oneself. Limited physical contact could enhance anti-social tendencies. Having everything delivered to the cell was convenient, but only if a sedentary life was preferred.

Tucked in behind a plexi-glass fronted black-steel door introduced me to how easy it was for those with a weak character to devalue the notion of respect. Many men saw the lack of consequences as an excuse to cast aside personal values. You might say their true colors shined through.

Was it all a reflection of who I had been? Who I was? How broken and sad would I have to be to share in their aggression that built up like a festering boil, bringing woe to whoever held the lance?

It all seemed like beat-my-head-against-wall insanity. Pacing a cell, how was I to know my own mind? Not even a tentative routine of cleaning, eating, walking, or reading legal material was bringing me closer to the inner silence I desired.

Or the sleep I needed.

All through April I tried to find a solution. Easter–Eostre’s Feast–came and went. My battles with Medical persisted: Judy (my former step-mother and a wonderful friend) was fighting with me, raising my concerns with an outside agency. The psyche-department wouldn’t reply to requests for help. Why? Simple, really: I was not suicidal; my anxiety and insomnia did not overly concern them.

* * *

In his article about sleep for National Geographic, Michael Finkel wrote: “The first segment of the brain that begins to fizzle when we don’t get enough sleep is the prefrontal cortex, the cradle of decision making and problem-solving. Under-slept people are more irritable, moody, and irrational.”

Self-test: Was I irritable? Well, I did want to hit Cain in the mouth. Moody? Would two punches be enough? Believing that violence would solve the problems I faced was definitely irrational. Yep, I was “under slept.”

“Every cognitive function to some extent seems to be affected by sleep loss,” said Chiara Cirelli, a neuroscientist at the Wisconsin Institute for Sleep and Consciousness.

Great. What was the solution? Run head-first into the cell door, hoping to knock myself out? I really was starting to contemplate extreme measures, when a guy from the psyche-department came around.

Mental Health issues, in 2010, were primarily handled by the unit psychology department. Supposedly one psychiatrist was capable of prescribing medication – psyche drugs that were a major hustle, leading to widespread abuse. Unless the need was great, or a person used the right “keywords” (like, “I am suicidal”) it was difficult to get a response or help.

But every three months, a person from the psyche-department would walk around with a clip-board, a roster of names. At each door he/she would ask, “Are you okay? How are you doing?”

The same questions I heard down the run, prompting me to approach my door. I didn’t expect much, but maybe I could use the interruption as a useful distraction — assuming the person (it sounded like a man) stopped to talk to me.

Soon he did. Upon seeing me his brows furrowed as he asked, “Are you okay?”

“No.” Wasn’t it obvious? I was in boxers and barefooted, sweating, clenching my jaw — obviously pissed off. My eyes were no doubt blood-shot. Acne had become an issue. And my hair was disheveled.

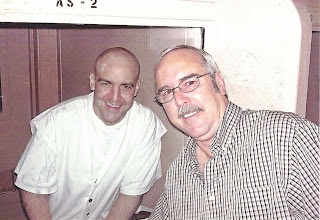

The guy before me was pale, older, with a scruffy white beard, wearing a blue button-down. About my height, he leaned closer to hear over the racket. “What’s wrong?”

“You’re hearing it and smelling it. I deal with this crap twenty-four hours a day. I can’t sleep. It is affecting how I think and feel.” I gritted my teeth as a neighbor yelled out an obscene slur. “This is driving me crazy.”

“You aren’t hearing voices?”

I sighed. “No.”

“No suicidal thoughts?” He watched my eyes.

I rolled them “No.”

“Ever tried?”

That was new. “Yes,” I replied. “A few times.”

He nodded. “I’m not telling you this.” After looking around, he lowered his voice, requiring me to step closer. “You need sleep.”

Not a question. I accepted it without replying.

“You have sinus issues.”

Again not a question. Interesting. Curiosity contorted my face, but I still did not say anything.

“Benadryl is helpful,” he told me. “You should see Medical about your sinus issue.”

For the first time in days, I grinned. “Okay.”

“You will be.” His smile was one of shared understanding, and then he walked off. That man told me what to say and how to manipulate the system, to get the medication I needed to sleep. The process was surprisingly easy. The sleep I got was a wonderful relief.

* * *

At the end of April, Judy finally contacted the Ombudsman, seeking to resolve my problems with the Medical Department.

Date: Fri, 30 Apr. 2010

Subject: Re: #1497519 — Terry Daniel McDonald TDCJ Michael Unit

My stepson, Terry Daniel McDonald #1497519, Michael Unit, Tennessee Colony, TX, attempted an escape at the Polunsky Unit in January of this year. He was shot twice — once in the upper arm and once in the back of his knee. The upper arm wound has healed, but the shot in the knee has not healed because the bullet is still in his knee. It is difficult for Daniel to walk; he has pain; he has to wear a support, and according to him no future treatment is planned. He is in for life and I find it very difficult to accept that he shall be required to spend the rest of his life crippled and in pain. I would appreciate very much your investigation into this matter.

Douglas B. King, PhD, Investigator III, Patient Liaison Program, responded:

Your correspondence addressed to the TDCJ-CID Office of Ombudsman was forwarded to the Patient Liaison Program for investigation and response to the medical issues raised. In your correspondence, you state that your step-son, Offender McDonald, is denied medical treatment for knee pain due to gunshot wound and a bullet still in place. Upon receipt, the facility’s University of Texas Medical Branch Correctional Managed Health Care (UTMB-CMHC) medical department was contacted, and the medical record reviewed.

Review of the medical record reflects that Offender McDonald was last evaluated by the facility UTMB-CMHC provider on 04/12/2010 at which time the provider assessed left knee pain. The provider renewed the offender’s prescription for Ibuprofen 600 mg three times a day with two automatic refills as Keep On Person (KOP). He picked up his last packet on 04/22/2010. Another KOP pack is currently available to him at his assigned pill window. Offender McDonald is also scheduled for follow-up evaluation by the UTMB-CMHC Orthopedic Clinic in June 2010.

The best part was the last sentence, because no appointment had been scheduled. What happened was, Judy contacted the Ombudsman, and then before she received the May 17, 2010 reply from the Investigator, I was called in for a tele-visit. I talked to the Orthopedic Specialist and THEN the appointment was scheduled. It was all a rush job, quite obvious to me. To show they were actually “trying” to do something. A little outside support went a long way. But that is the norm; those who lack support face the greatest abuse, because there is limited oversight by outside agencies.

* * *

I am thinking about the wisdom Victor Frankl expressed in his book, “Man’s Search for Meaning.” He wrote: “Being human always points, and is directed, to something or someone other than oneself. The more one forgets himself — by giving himself to a cause to serve or another person to love — the more human he is.” It only took three years in a concentration camp to lose his pregnant wife and parents, yet he did not despair. Instead he found meaning — which is about transcending the present moment — in his work as a psychiatrist.

“A man who becomes conscious of the responsibility he bears toward a human being who affectionately waits for him,” Frankl wrote, “or to an unfinished work, will never be able to throw away his life. He knows the ‘why’ for his existence and will be able to bear almost any ‘how.’”

Frankl‘s words, and what he endured, gives me pause. All that he lost and worked through is a source of inspiration, because it would be so easy to get lost in each moment of suffering. Upon reflection, I was but one of the estimated 8,764 individuals in AD-SEG back in 2010. 1,960 of those people had a serious mental health or mental retardation diagnosis. We were all mixed in a way that suffering was often shared when the mentally wounded acted out.

My suffering was shared, and reduced, because I had support from some remarkable women who refused to give up on me. They helped me to reevaluate what I deemed important in life, leading with relationships. I did not deserve their love and dedication — there is a debt I can never repay.

Of course my mother led the way, though she struggled with my inexplicable actions that led to self-destruction. I certainly did not have a true view of myself, so when she wrote and asked if I have a “death wish,” the question seared to my core. Did I want to die? Not really, no. But I knew that I had spent years waking up asking myself, “Do you want to keep living?”

Was that question to myself the same thing? Was my Mother’s inquiry highlighting a shadow she’d long suspected? It just might be that I had been living closer to death than life, and I really wanted to change the direction of my thoughts. One thing was for sure, I likely had not been giving myself “to a cause to serve or another person to love.” I definitely lacked a full awareness of my responsibility to others, the “why” of my existence.

It was very trying to have to figure all of that out in a cloistered, chaotic environment. But then it may have been the best way to instill the lesson in a way that I would never forget.

Because, you see, the escape attempt was about needing to get away. To be somewhere else, to be free of fear, yes, but really to escape myself, which is why the consequences were not considered. I essentially ran blindly into a hail of bullets.

So maybe my Mother was onto something.

When I wrote Mom back, I assured her that I did not, in fact, have a death wish. But I also admitted that I was living a day-by-day existence on a path of slippery stones.

Judy and Linda are sisters. Their role in my life came late (especially in Linda’s case), but it has been profound. Judy was married to my father until 2000. Once I was in the County Jail, she reached out to me — the woman I once hated soon became a wonderful confidant and friend. When it came time for my trial, she brought Linda. I had never seen Linda before, never talked to her, but when they sent me to prison, she wrote and asked how she could help. Now I simply could not imagine what life would be without them.

My Aunt Rayne found me in population, writing often and deeply about shared trials. Pain. Love and need. I got to explore failure with her, and the possibility of redemption.

Their letters were rays of light, a calming force when I felt on edge. Once I was able to sleep, thanks to the Benadryl, my days became easier as my daily activity swirled around how they valued me. In not giving up on me, I found greater strength so that I did not give up on myself and others.

I even started to see the path I truly needed to walk. It was one I knew well, my favorite place in the world: the water garden in Corpus Christi, Texas. Back then I couldn’t see it all, though, only the concrete path, which lay over a shallow stream of water.

That pathway became my point, directing me outside myself, toward a place where I could truly relax. As an unfinished work, I dedicated time each day to the task of being a better version of myself. Even when my knee would slip out of place.

But I expected that to get fixed soon.

No Comments