By Thomas Bartlett Whitaker

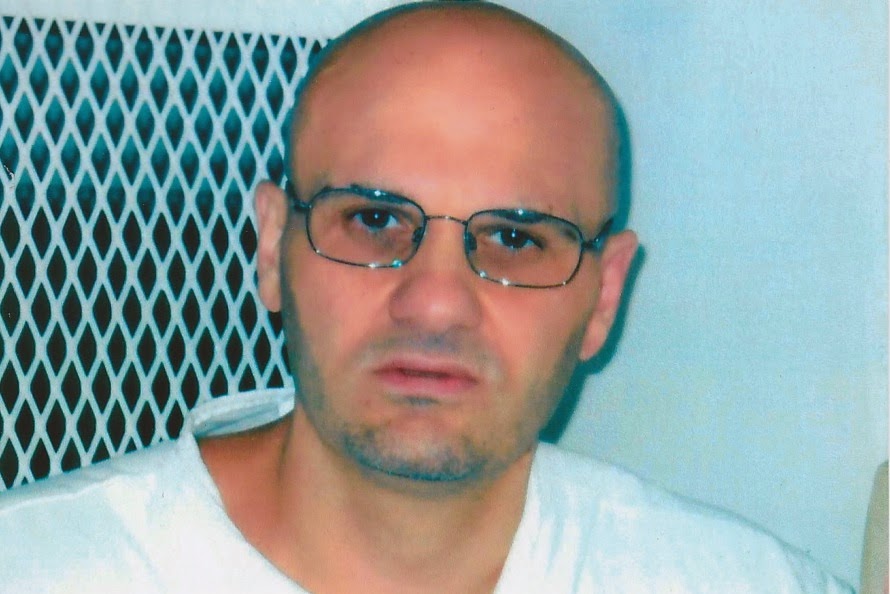

which Beckcom had arranged to be taken in the visitation room of the federal prison on Thanksgiving Day. This was “proof,” the state claimed, that Beckcom was very close to Jeff. By extension, Siegler went on to claim, Beckcom’s testimony was therefore veridical.

Placed inside one of these cages, one can have a shouted conversation with the men in each section. On this particular day, an inmate named Jaime Elizalde (executed by Texas on 31 January 2006) asked Jeff if he had ever been in federal prison before. Jeff replied that he had spent several years in the complex in Beaumont. Jaime told him that he had a good friend in federal prison and that this friend’s wife recognized Jeff and his parents when she came to see Jaime. He told Jeff that he was responsible for the murder of Albert Guajardo, a crime the state had erroneously pinned on his friend, Hermilo Herrero. He shot a fishing line to the dayroom and showed Jeff an article from the Houston Chronicle detailing the Herrero case, complete with photographs of the principle players. When Jeff read the article and looked at the photographs, he had to sit down because the world began to spin on him. Kelly Siegler had prosecuted Herrero: his was one of her “waiting on God” cases, exactly as Jeff’s had been. The homicide detective handling the investigation was Curtis Brown. Herrero had been convicted based on jailhouse snitch testimony involving two inmates at the FCI Beaumont Medium facility named Jessie Moreno and Rafael Dominguez. Jeff knew these men. They were both friends of Nathan Foreman and Michael Beckcom.

2 Comments

Anatomy of a Wrongful Conviction – Day Five - Minutes Before Six

April 28, 2023 at 6:44 pm[…] 2 By Thomas Bartlett Whitaker To read Day Four, click here. It is a fair assessment to state that Jeff Prible’s life depended largely upon identifying […]

Anatomy of a Wrongful Conviction – Day Three - Minutes Before Six

April 28, 2023 at 6:41 pm[…] probably would have been more careful. Instead, he was a sitting duck. To read Day Four, click here Ronald Jeffrey Prible 999433 Polunsky Unit 3872 FM 350 South Livingston, TX 77351 Thomas […]