By Thomas Bartlett Whitaker

To read Day Four, click here.

It is a fair assessment to state that Jeff Prible’s life depended largely upon identifying and locating the man known as Walker. This would prove to be a frustratingly difficult task, not due to the magnitude of the problem but strictly because of the tools at Jeff’s disposal. His state habeas attorney, Roland Moore, initially hired investigator John Greenfield to assist in the case. According to Greenfield’s testimony, he was unable to find the Walker of Jeff’s story because, he claimed, Walker was a very common name in the Bureau of Prisons. Consider me unmoved by this assertion. The last time I checked, the BOP had around 200,000 inmates. Clearly, there exists a database of these inmates because if there is one thing prisons do well it’s making sure it knows where its inmates are located. How many Walkers could there be? Fifty? Why not send them all letters until you find the right one? Apparently such logic made no sense to Roland Moore, and I suspect that this had everything to do with the fact that he simply didn’t believe Jeff’s tale; not being listened to by one’s attorneys is pretty much the one thing all Texas Death Row prisoners have in common. Jeff had been growing increasingly more frantic by the month, so in order to placate him Moore did attempt to interview Foreman. The head snitch wouldn’t say one word to him once he found out who he represented. Beckcom proved even harder to get to, as his attorney wouldn’t allow Moore to even speak with him. Moore simply gave up and filed an application for a writ of habeas corpus, which completely omitted the entire issue of the snitch network and the prosecutorial misconduct that had created it.

Almost immediately Jeff began to file his own paperwork, which ultimately amounted to several hundred pages of handwritten documents. In legal terms, these included very pro-se-ish pleadings involving Brady, Giglio and Massiah violations, as well as an ineffective assistance of counsel claim. He also attempted to file a subsequent writ of his own. Interestingly, the clerk in Harris County did not immediately file this intended successor writ with the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals, as is clearly required by law. Instead of labeling Moore’s write the “A-writ” and Jeff’s as the “B-writ,” the clerk only sent the latter as an attachment to the A- writ five months after it was submitted. It would later be dismissed as “abuse of writ,” one of the standard strategies used by the TCCA to sweep troublesome cases under the rug.

Once “abuse of writ” has been declared, the entire writ and all of the factual evidence contained within it is procedurally barred. The general public can always be counted upon to be ignorant of the inner workings of the law so you need to pay attention to this if you are all of the opinion that your court system is honest and fair. If you are convicted of a crime, and then later come across evidence that proves your innocence only after your first writ has already been considered by the TCCA, there exists a very good probability that this new evidence is forever off limits to you. You could literally have a sworn affidavit and a video confession from your prosecutor admitting to having actually committed the crime you were convicted of as well as a detailed diagram submitted by him explaining how he set you up, but if you are hit by the abuse doctrine you are screwed. I have probably known at least twenty-five men who went to their deaths over this issue, so it is very real, very lethal, and entirely an invention of Republican judges.

While the TCCA’s habit of using the abuse doctrine is certainly heinous, in this case it was particularly uncalled for because in order for a writ to be considered a writ in the first place it must contain specific factual allegations. Jeff’s attempted successor writ had no such specific facts at this point, only guesses, hearsay, and vague allegations. According to their own precedent, the TCCA should have dismissed Jeff’s B-writ without prejudice, which would have allowed him to bring up his undeveloped claims at some point in the future should new facts come to light. Instead, they bypassed their own system and precedent and effectively barred him from ever questioning the tactics of Kelly Siegler in state court. Even his allegations were too damaging to be looked upon in open court, it would appear. When Jeff sent a copy of this B-writ to Moore, he responded curtly: “I have received your successor writ. None of it is useful. I will not be adapting it.”

It is possible that Moore’s refusal to vigorously investigate Jeff’s claims has a motive beyond pure laziness or incompetence. Again we must delve into the realm of speculation, as the following allegations have not been proven in court and are not even included in Jeff’s federal court briefings. In Texas, we elect our state court judges. These elections are just as partisan as those for congress, with the winner usually being the candidate who can get the most worked up about the need for swift justice, a quality which, apparently, some people believe Texas is somehow deficient in. Elections cost money, and judges solicit campaign contributions just like any other politician. These campaign reports must be filed with the Texas Ethics Commission on a semi-annual basis, so anyone with knowledge of the Open Records Act can get their hands on them. The Texas Code of Judicial Conduct provides that judges:

– “[avoid] impropriety and the appearance of impropriety in all of the Judge’s activities” (Title of Canon 2).

– “should act at all times in a manner that promotes public confidence in the integrity and impartiality of the judiciary” (Canon 2 (B)).

– “shall not make unnecessary appointments. A judge shall exercise the power of appointment impartially and on the basis of merit. A judge shall avoid nepotism and favoritism” (Canon 3 (c) (4)).

– “Shall refrain from financial and business dealings that tend to reflect adversely on the judge’s impartiality, interfere with the proper performance of the judicial duties, exploit his or her judicial position. (Canon 4 (D) (1)).

Cross referencing Judge Mark Kent Ellis’s campaign reports with the names of Jeff’s appellate attorneys produces some very suspicious results. Jeff’s direct appeal attorney was a man names Henry Buckholder; his state writ attorney was Roland Moore. Neither adequately defended him, and both gave Judge Ellis precisely two campaign contributions. The first set of donations were given on the exact same day, 28 September 1999, before they were awarded the position of defending Jeff in the appellate process. The second set of contributions was given after their appointments. The sums are interesting, as well. Buckholder gave $ 1,000 to Judge Ellis, ten times more than he gave to any other judge. One can’t help but wonder if this was because he wasn’t on the Second Administrative Judicial Region’s list of qualified counsel for appointment in death penalty cases, and thus not even eligible to be appointed in the first place. Roland Moore also happened to give more money to Judge Ellis than any other judge by a large margin.

In a period from July 1999 to February 2008, Judge Ellis received donations from ninety different individuals. Eighty-five of these came from attorneys and two came from court reporters. An astounding sixty of these contributions were made during a five-day period from 27 September 1999 to 1 October 1999. This frequency strongly suggests that these donations were requested by the judge, as it is very nearly statistically impossible that two thirds of the judge’s total contributions for nine years would have all been randomly received over such a brief span of time. One wonders what Judge Ellis needed the money for, as his campaign expenditures since 1 July 1999 totaled only $ 1,242.71, far less than the nearly $ 30,000 he took in. Interestingly, the periods in which Judge Ellis recorded the majority of these contributions coincides exactly with periods in which the Harris County Republican Party was fundraising. Judge Ellis in fact gave most of his campaign contributions to the party, which in turn paid his filing fees, promoted his campaign, and ran an attack ad against his opponent. One could easily argue the appearance of an “impropriety” given this data, if one were attempting to be formal and polite. One could also call this bribery or a kickback scheme, if one were attempting to get to the point.

Jeff’s original trial counsel (Terrence Gaiser and Kurt Wentz) never contributed money to Ellis’s campaign. They didn’t need to pay to play, because trial counsel is selected off of a pre-set list, where the next available lawyer gets the next case. Appellate counsel, on the other hand, is awarded at the judge’s discretion. One can see how such a system practically invites corruption. After all, tossing a thousand bucks at a judge in order to be awarded a $30,000 case is not at all a bad investment. Especially, I might add, if you are a lawyer not prone to exhausting one’s contracted funding on pesky matters like investigations. This, I believe, was precisely the point with the appointments of Buckholder and Moore. I have no way of proving these two claims, but I believe that Judge Ellis very specifically selected these two clowns because he knew from past experience that they were not going to put up much of a fight on Jeff’s behalf. Why? Because it was obvious that the trial he oversaw was riddled with errors. Ellis, a longstanding judge, knew as well as the prosecutors and the defense attorneys that the State’s DNA expert had lied, and he knew as well as them that Beckcom’s testimony was blatantly self-serving and full of holes. Last, but certainly not least, Judge Ellis needed a weak appellate team for Jeff because he and Kelly Siegler are old friends. When Siegler ran for the District Attorney’s office in 2008, Ellis was one of her campaign managers. In March of that year I spent a week at John Sealy hospital in Galveston. Since I had not seen a television in a few years, I spent quite a bit of time flipping channels. I am something of a political junkie, and I still very clearly remember watching a program on the local PBS station regarding the upcoming citywide primary elections. Given the importance of the position, they spent nearly thirty minutes covering the Republican race for the DA. They showed a clip of Siegler on a small stage at some rally, haranguing about the need for a more “experienced” pro-law enforcement candidate than the moderate Pat Lycos. The man standing to her right clapping vigorously? Judge Mark Kent Ellis. He wasn’t the only conservative judge on the stage, and I can’t help but wonder how many capital cases Siegler has tried in the courtrooms of judges friendly enough with her to be seen on stage with her at a campaign rally. As the local fixer says of the supposedly “blind Lady Justice” in the movie Sleepers, down here the bitch got eyes.

Because Jeff’s appellate counsel were either idiots, lazy, or on the take (or a combination thereof), Jeff had no real means of locating the mysterious Walker that had been a part of the snitch ring. When he attempted to write to inmates that he knew from FCI Beaumont, the Polunsky Unit mailroom clerks confiscated the letters on the grounds that these attempts at communication violated a rule prohibiting Death Row prisoners from having any contact with other inmates. When Jeff attempted to use the laughably toothless administrative grievance system in the TDCJ, the authorities didn’t rule on any of the merits of his grievance. Instead, they simply stamped it “denied” with the claim that his complaint wasn’t even a grievable issue. Even Jeff’s letters to friend and anti-death penalty activist Ward Larkin requesting that he contact certain inmates were confiscated. Despite this fact, Jeff was able to communicate what he needed in the visitation room and Ward began attempting to locate all of the Walkers in the federal system. To his credit, he narrowed it down to a single likely Walker and began to send him regular letters. As it turns out, this Walker, a Larry Wayne Walker, was the wrong guy, but, in one of those near miracles that pepper this case, his cellie knew and was friends with Carl Walker. One day, Larry Wayne began to complain to his cellie about getting all of these letters about some white dude names Jeff Prible, and the cellie happened to mention it to Carl. He instantly knew what the letters were about.

One of the reasons it took Ward some real effort to find the right Walker was that Siegler had done her job well: after testifying in the cases of Herrero and Jeff, she scattered her agents across the country. During Herrero’s April 2002 trial, for instance, Foreman was transferred by writ from FCI Beaumont to an in-transit prison in Englewood, Colorado; this was one of the reasons that Herrero was held in the Harris County Jail for six months after his conviction, as relayed to Jeff in his initial letter. Siegler simply needed a few months to affect the necessary transfers so that Herrero wouldn’t discover how he had gotten screwed at trial. Beckcom was shipped to FTC Oklahoma City on 17 March 2003, immediately after Jeff’s trial. Moreno, the snitch that first met with Siegler and gave her Foreman’s name, also went to FTC Oklahoma City on 12 June 2002, immediately after Herrero’s trial. Similar evacuations from Beaumont would take place for every last member of the snitch ring, an obvious attempt to make it vanish into thin air. Carl Walker himself would be transferred several times, ending up in Oakdale, Louisiana, even though he had backed out of his role in manufacturing Jeff’s confession.

Siegler’s attempts to bury her informants did not stop there. In the early phases of the set-up, there was a degree of confusion over which of the snitches would inform on Herrero, and which on Jeff. In his statement, Carl Walker claims that several of the men even wanted “action” on both cases. During this period, before the final plan was set in stone, someone typed up three affidavits purporting to be from Carl Walker, Jesse Gonzalez, and Mark Martinez, all inmates at FCI Beaumont. These statements are internally consistent with each other, but stray somewhat from the actual facts of the case; it is fairly obvious that they were written by someone with a superficial understanding of the case against Jeff. We don’t currently know who wrote these statements. Beckcom denies having typed them, but does claim to know of their existence, a rather odd assertion but consistent with the type of person who only incidentally possesses a pistol in the midst of a kidnapping and murder. You can see these statements here, here and here. You will quickly notice that all of these affidavits use the same exact format, i.e., similar use of the tab key, headers, and “Re”line. The grammatical style is also eerily similar in all of the letters, if we are to believe that they were, in fact, written by three different people on three separate occasions. Whoever wrote them also misspelled Jeff’s last name in all three statements – and did so in exactly the same manner. The statements by Gonzalez and Martinez violate the cardinal rule of lying, which is to keep your story simple and infused with as many truthful elements as possible. For instance, they both claim to have known Jeff and Steve Herrera from the neighborhood. Martinez even goes so far as to claim that he was at Steve’s house the night before the murders and witnessed the two arguing, apparently unaware that Steve’s brother-in-law was also present and would testify that the two spent the evening on good terms. Gonzalez claims to have known Jeff when they were younger in the first portion of his statement, yet the second half says he couldn’t “place him” until he saw his face. The statements all assert that Jeff confessed to a large group of witnesses, despite the fact that Beckcom would testify in court that only he and Nathan Foreman were present.

These statements were never used at trial, and none of the three men who supposedly signed them were called to testify. It is safe to say that there is not a prosecutor in America that that wouldn’t be thrilled to have three different witnesses to a confession, so why weren’t they used? Quite simply, even Siegler realized that the statements were too foul to be utilized. They contained too many details that could be shown to be false, such as where certain people were living during certain time periods. This would have been very simple for the defense to verify or disprove using tax records. When the data showed, for instance, that Gonzalez actually lived nowhere close to Jeff’s neighborhood during the years in question, his entire testimony would have been impeached.

The statements were also problematic for Siegler in another way, in that they clearly identified the names and BOP identification numbers of some of the members of her snitch ring. This was information that she desperately needed to keep from the defense, because a single loose tongue could lay to waste her entire career. So, even though these statements might have sealed the fate of Jeff if they had been more professionally rendered, Siegler buried them in a file she labeled as “Attorney Work Product,” a technical designation that prevented them from being handed over to Jeff’s defense team when they filed for discovery. I have no idea why she didn’t destroy them, save for the guess that back in the early aughts, it would have seemed incredible to her that the entire Johnny Holmes faction of ultra-tough prosecutors to which Siegler belonged would be run out of the building. I imagine that she simply assumed that she or one of her followers would always be present to protect these old convictions. When Jeff arrived in federal court, however, Pat Lycos had come to power and she did not fight the order filed by US District Judge Keith Ellison requiring the entire state file to be handed over. It was at this point in late February 2011 that the affidavits were discovered, a full year after they were alluded to by Walker in his statement.

The most important fact regarding these statements is also perhaps the simplest: not a single one of them had been typed or signed by the men whose names they bear. When Jeff’s federal attorney contacted Mark Martinez, he outright denied having had anything to do with his letter, and admitted that some FCI Beaumont inmates were pressuring others to sign statements incriminating Jeff. Martinez’s FCI Counselor, Olmstad, then compared the known exemplars of Martinez’s signature to the one present on the statement sent to Siegler and was absolutely certain that Martinez had not signed the letter. Walker knew of the letter written in his name, but never knew whether it was sent or not because he backed out of his participation in the scheme. Had Siegler not deliberately flouted the law and withheld these letters, Jeff’s trial counsel would have been able to locate Carl Walker prior to trial, and would have used his testimony to blow Michael Beckcom off of the stand. Had they known about the letters, there probably wouldn’t have been a trial at all.

The whole story finally unraveled when Ward Larkin located Carl Walker. He was first interviewed by Jeff’s investigator early in 2009. You can read a statement detailing this meeting here; it’s fairly short and will only take you a moment to cover. Also attached to Walker’s statement is a brief account of a conversation this investigator had with Thomas Delgado, a former FCI Beaumont inmate that Foreman had attempted to recruit into the informant network. About a year and a half later, Jeff’s federal attorney traveled to Louisiana to meet with Walker. The interview was recorded, and I will leave a copy of the transcript below. It’s a fairly lengthy interview, but it is so astoundingly detailed that it reads something like a novel. During this conversation, Walker explains how Foreman and Beckcom attempted to recruit him based off a very specific set of qualifications. It was important to them that Walker be a church member, for instance, as well as a first time offender with a very lengthy sentence. They were looking for young, desperate inmates with no record of snitching, someone they could mold into their image. They pitched their plan to him by saying that Jeff’s imminent arrival at the medium prison was a blessing, a chance to do something good for the Lord. Before Jeff ever arrived, Walker knew highly specific details about the murders, such as where the bodies were laid out in the burnt home, something he acknowledges he could not have known had the information not come from either the state or Jeff. As Walker states near the end of the recording: “Prible was dead the day he hit the yard. He just didn’t know… they had already baked a cake for the man.” I’m always posting links at the end of my articles, and I seldom know how many of you actually follow them. You will want to read this one, especially the second half. If I haven’t quite closed the coffin on the argument that our criminal justice system is even more broken than the men trapped within it, I suspect that this interview will hammer the final nail home.

Of course, this story wouldn’t be complete without hearing from Michael Beckcom himself. He’s out of prison now, a free man. In June of 2010, Jeff’s investigator tracked him down. He was understandably wary of being recorded at this initial meeting, which took place at a Denny’s restaurant. Two months later, Jeff’s investigator spoke with Beckcom at IHOP and then wrote a formal statement detailing the conversation. You can read this here.

It’s pretty revealing, even considering how cagey he was being. The worst part of the interview comes at the end, when Jeff’s investigator informs Beckcom that Siegler had lied to him and the other snitches about having a deal lined up with federal prosecutors to arrange a Rule 35 sentence reduction in exchange for his testimony. No such deal existed, because Jeff’s case took place in the state courts and the federal authorities had “no jurisdiction to confer any benefit” on Beckcom. When he found out that Siegler had lied to him, he said: “I knew she did it after it was all said and done. She’s a fucking cunt, she really is…she got smart. She got another notch in her belt. That’s all it was. She had aspirations. She had an agenda.”

For all his lies, for all his effort, Michael Beckcom’s thirty pieces of silver turned out to be as fabricated as his testimony. I’d say there was some justice there, if it weren’t for the fact that an innocent man is still sitting on death row.

To read the transcript of James Rytting’s interview with Carl Walker Jr. please click here.

To read Day Six, click here

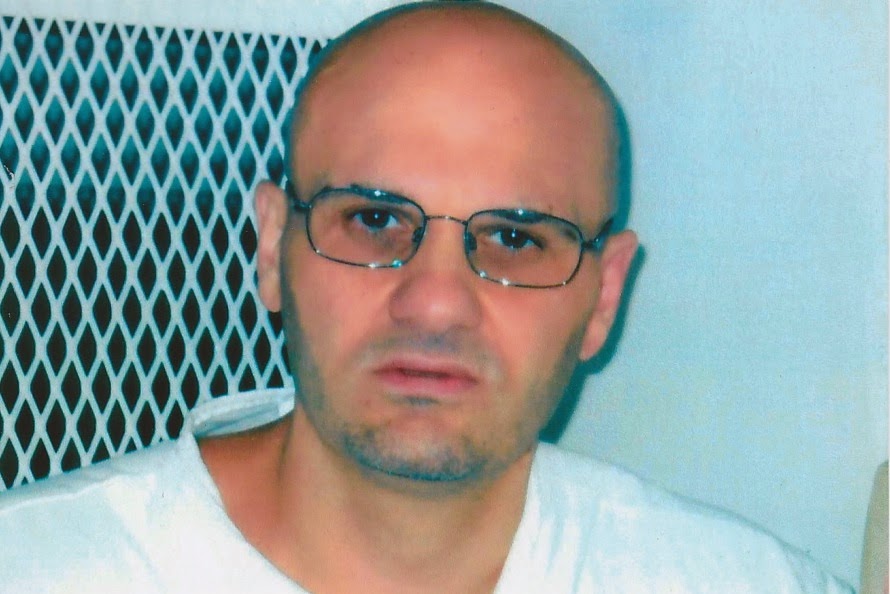

Ronald Jeffrey Prible 999433

Polunsky Unit

3872 FM 350 South

Livingston, TX 77351

Livingston, TX 77351

3 Comments

Anatomy of Wrongful Conviction – Day Six - Minutes Before Six

April 28, 2023 at 6:46 pm[…] 0 By Thomas Bartlett Whitaker To read Day Five, click here If, as I argued at the beginning of this series, the primary driver of wrongful convictions is […]

A Friend

September 2, 2014 at 2:53 pmThank you for your comment. The mistake you are referring to is in a supporting document, not in the text of the article, so it's not an error I can correct.

Braatmom

September 2, 2014 at 2:51 pmIn the sixth paragraph of the account of Walker's statement there appears to be a mistake. (attachment "D") It reads "Walker said that Beckcom arranged for Prible's family to meet Prible's family…."

Anna Mustaine