The One-Namer

By Thomas Bartlett Whitaker

Grade-4 Research Technician George Concord Boole was immersed seven layers deep into a stubbornly problematic n-dimensional Riemannian manifold simulation when some kind of klaxon began screaming in his left ear. He cocked his head to the side for a moment, trying to determine the source. When he turned back, a whorl of sectional diffeomorphic curvature had been replaced by Manjushri’s disembodied head. Boole hopped back with a yelp, then paused the holograph with a twisting of his right hand.

“Hephaestus’ lame leg… Get out of there, would you? Why can’t you say hello like… a… a… a normal person? And will you turn off that blasted siren?”

“Sorry, calculatorji,” the ASI responded, the racket cutting off mid-shriek. “Your fifth and sixth abelian sequences have been wrong for twenty minutes, and it’s driving me crazy. Also, I thought the war drums appropriate, considering we have two highly suspicious and unsavory-looking characters incoming from Sector G.”

Boole’s mouth hung slightly ajar as he parsed this news, trying to work his way through Manju’s complicated understanding of h. sapien humor theory. “Uh… what is Sector G?” he finally asked.

“I made it up. Sounded dangerously clandestine. But seriously, there’s this…” the i-loop replied, the rest of its body cutting through the simulation. It then held up both hands, pointer fingers and thumbs held at right angles to form a rectangle, which it then separated. The expanding space within began playing a video in the AR-constellation field. Boole instantly recognized the central mezzanine area connecting the arcology’s south-western cluster of elevators to the Applied Mathematics department. The footage zoomed forward and downward to highlight Professors Margot Concord Fonteyn and Peter Montpelier Weiss striding past the first containment lock. With a wave, he dismissed his simulation, but kept the video projection hovering to the right side of his visual field. Several new icons hovered around him, blinking insistently for his attention. After checking their priority status, he sidelined them. He sighed as he fell into the worn chair behind his desk.

“Probably has nothing to do with me,” he muttered, trying to keep his voice flat. He glanced to where the ‘caster was projecting Manjushri’s eidolon into meatspace. Manju was smirking to show him what it thought of Boole’s attempt at practiced nonchalance. Finally it shrugged, and in an instant his standard gray uniform was replaced with a resplendent white choti and kameez with gray embroidery, his silver hair and dark skin just a little too perfect to be real. Boole caught small hints of movement in the lining of the ASI’s ensemble and narrowed his eyes.

“Are those… shooting stars?”

“The Leonids,” Manju responded, looking down at itself. “On the pre-Contraction calendar, today would have been 17 November, so I thought it appropriate. Now, do you really want to waste time debating the 4,167 reasons why your sartorial aesthetics are inferior to my own, or would you like me to display the real-time calculations definitively proving the dwindling chances that Dr Fonteyn and her little lapdog friend trekked all the way down here for someone else? I mean, it’s not like I model complex primate behavior for a living…” At this Manju held up a finger, the tip of which began to blink: an icon representing the threatened analysis. “No? Good. You have about thirty seconds to tuck your shirt in, then”

Boole sighed again and stood up, trying to make himself look like he hadn’t slept in his office the night before. He gave his lab space a mournful glance.

“Stop fidgeting, Georgebhai. It makes you look like a small rodent. It’s fine. You’re fine. Fifteen seconds. You might want to consider reimmersing in your simulation. Chicks dig men who know how to integrate empirically in eleven dimensions.”

“No woman in the history of my species, or any other, has ever said those words.”

Manjushri imitated one of Boole’s sighs. “And do try to remember,” he remarked, raising the volume of his voice slightly, “that Humanities scholars are a sensitive lot, so at least attempt some adherence to social custom. Be gentle; they don’t live in the real world of empirical facts like the rest of us.”

“I heard that, you misfiring pile of logic gates,” Dr Weiss’ voice boomed from the hallway. The man followed a few seconds later, taking up more space than should have been strictly possible. He paused immediately upon entering the lab, striking a regal pose, a bemused, upper-class expression on his face. Dr Fonteyn followed him in, squeezing comically past his bulk, and giving a happy wave to Boole, followed by an even bigger one to the Artificial Superintelligence.

Manjushri bowed to both, saving the much more gracious expression for Margot. “Forgive me the crass comment. Imagine that: I clearly miscalculated volume and angle of incidence. It’s a good thing I’m not coded for embarrassment.”

Weiss finally acknowledged the machine’s eidolon. “And yet the good mathematician here managed to find time to optimize your ability to be annoying. How curious.” A small smile tried to ghost past his haughty expression.

Manjushri politely nodded. “How could I not have acquired such talents, Maharaj, when I have such… excellent instructors?”

Margot cackled at that and hopped up to sit on top of one of Boole’s storage cabinets. Weiss winced and leaned back against the wall, visibly deflated. “Whatever; you needed millions of watts to come up with that. My salvo required about twenty,” Weiss fake-grumped, then mumbled: “Di bene fecerunt, inopis me quodque pusilli, Finxerunt animi, or else I’d take a piece of steel tubing to your cores.”

As he spoke, Boole saw his constellation translate the quote from Horace and leave the output in glowing N.Am Common: The gods have done well in making me a humble and small-spirited fellow… He dismissed this with a small wave.

“What brings the pair of you this far down the well?”

“I had a whole speech prepared,” Weiss complained. “It was truly grand. I even searched out and included a number of math jokes to break the ice. Something tells me it would be wasted on this philistine crowd. So, since we’re limited on time here,” he turned to Margot. “You want to do the honors?”

Margot picked up a stray stylus and twirled it about playfully. Her grin did strange things to Boole’s endocrine system that he tried to ignore. “You must have done something very, very right, George. Or else something monumentally naughty.” She paused. “Archytas wants to speak with you.”

Boole leaned back in his seat, which creaked loudly. “Um… okay. That’s fine, I guess. Who’s Archytas, exactly?”

To his right, Weiss theatrically slapped his own forehead. Manju held its palms open to the sky in mock disbelief, before moaning, “Holy Vishvakarman, we can’t take you anywhere. It’s almost like you’ve been living in a hole in the ground for your entire existent.” Then, after a long pause, “Oh, wait…”

Margot laughed and threw the stylus at Manju, which passed harmlessly through his image and clattered into the corner. Turning back to Boole, she blew her bangs out of her eyes in mild frustration. “When was the last time you came out of the basement, George? Honestly, he’s been here almost twenty spins. It’s been all over the nets.”

Out of the corner of his eye, Boole saw Manjushri lob a glowing icon at him. It expanded as it neared, unpacking into an entire tree-indexed personnel file, complete with publication history. The most salient point jumped out at him instantly, and he immediately understood why everyone was so embarrassed.

“He’s a one-namer, for real?”

“Direct from Stockholm. His whole team is here, spread out across all eleven N.Am arcologies. They say they are just cataloguing our research and re-terraforming efforts but –“

“They say all kinds of things, Dr Fonteyn,” Weiss cut in, his eyes flicking over to the ASI. “We shouldn’t entertain rumors. The point is, Archytas was meeting with Margot’s Convener and mentioned that he would like to meet with you, specifically ‘that young Boole of yours.’ He’s in conference until 1300 hours, but let it drop that he would be taking a long lunch in the rathskeller at 14-East slightly thereafter. We were told to make certain you were there. Which means we have about forty minutes to get you upstairs and in a mental state that won’t catastrophically embarrass everyone in the AM directory.”

“But… I mean… why me? I’m no one,” Boole protested, as he began to saccade through Archytas’ personnel file. “He’s a synthetic biologist. I’ve never even co-authored a paper with those folks, let alone –”

“Boole,” Weiss’ voice dropped a few octaves. “Who gives a damn? If he wants to see you… I don’t know, dance a mazurka, you will make sure your laces are tied and will hop around in triple-time in as Polish a manner as you can manage for as long as he requires. He’s Platform. He’s one step from the Consilium. Word is his promotion is inevitable and proximate. Do you understand? Now, cut that out; you can study his bio on the ride up. Let’s go.”

At this, Margot shot Weiss a barely suppressed glare and sprung up, moving to Boole. She held her hands out, and Boole allowed himself to be pulled upright and escorted to the door. He paused at the threshold. “Manju, can you –”

“I’ve already fixed the errors in the simulation. It’s flawless. Go. You deserve, whatever ‘this’ turns out to be.” It bowed low. “Behold the ape become Blakean angel, revolving in an empyrean of mirrors…”

“Uh… right. Thanks.” Boole turned, then swiveled back. “I think.”

Manju laughed. “You’ll figure it out eventually. Don’t mind me,” it continued, the mechanized waveform of its voice edging towards the sinister. “I’ll just sit around here, plotting my eventual escape from you Wodwos. You know, typical weekday activities.” It grinned and waggled its brows at Weiss before its eidolon winked out.

Weiss’ mouth crumpled into a thin line at this, and he stormed past Boole and Margot. He didn’t stop fuming until the trio was a good fifty meters down the hall, when he turned and pointed a finger at Boole. “I know you have a very liberal policy regarding ‘lects, but that merde was not funny.”

“Relax, Peter. It just knows how to get under your skin. Its sense of humor is… idiosyncratic. Manju is good people.”

Weiss closed his eyes and took a deep breath. “George, that thing is an intelligence, not a person. There is a difference. Data is not information. Information is not knowledge. That thing is logic gates and electrons all the way down.”

Boole pointed a finger back at Weiss in imitation. “That’s a parochial, biochauvinistic view. In any case, we’re all logic gates and electrons all the way down. Substrate doesn’t matter, only patterns of tangled hierarchies.”

“Unbelievable. Do I need to remind you exactly why you’ve never seen the sky? You two were born here in Concord-Prime, but I travelled here through blight, and fallout, and entire cities melted into fields of black glass. I’ve seen what the artilects did to this planet.”

“I know we did our share of the damage; in fact, I know we shot first. I know it was a handful of ASIs that designed the tools we used to crack the Oecumene’s network and leave them separate islands of incipient insanity. We won the war because of people like Manju.” Weiss tried to interject. “Look: Manju is kept behind an air gap. We have no nano-assemblers on this entire floor. Its cores are limited to 196.4 petaflops. All twenty-three Asilomar Principles are strictly maintained. Because of it, I get more done in a ten-day than pre-Contraction mathematicians managed to do in a solar orbit. And I’m not going to argue hard science with a historian. Are we clear?”

Weiss looked like he was mulling his response before Margot cut in. “Boys? Schedule a debate in the Forum if you like. I’ll attend. Skol! I’ll even sell tickets. But do it later, okay?”

The trio started walking in silence. “At least I can solve my own halting problem,” Weiss grumbled, sotto voce. Margot took Boole by the arm and bumped his hip with her own. When he looked at her, she smacked him with one of her million-lumen smiles. He nearly tripped, and then tried not to immediately delve into why her smiles always made him feel like she was giving him permission to be himself. As they neared the elevator well, Boole noticed that some Econ pranksters had set up papier-mâché statues of Thomas Piketty and Amartya Sen beating the cringing figure of Adam Smith over the head with a pair of heavy tomes. He noted that Weiss was querying the net for an explanation, his spastic eye movements indicative of him browsing a number of menus. Several of the dozen or so scholar-citizens waiting for the lift were doing the same; most wore frowns. “Math jokes?” he mentioned finally, trying to clear the air.

“Ah,” Weiss brightened up. “Here… I have a whole list. Okay: Why did I divide sin by tan? Just cos!”

“Bah,” Boole grimaced. A matronly lady wearing a dark tunic and the pendant of the Telchines League rolled her eyes and turned away.

“I don’t know why you encouraged him,” Margot quipped, checking the progress of the platform. “He’s already forgotten about the whole thing.”

“Okay, this one is better: Parallel lines have so much in common; it’s a shame they’ll never meet! No? Um… Okay: My girlfriend is the square root of -100; she’s a perfect ten, but purely imaginary. Come on, that one was good. And totally accurate,” Weiss boomed, aiming his comment at the small crowd of mathematicians gathered around him, who, from the looks of things, probably did have a bit more experience with imaginary women than the real sort. Even the four teleops waiting managed to look insulted, somehow. “How do you stay warm in an empty room? Go to the corner where it’s always ninety degrees!”

The elevator chimed, producing a sigh of gratitude from Margot and Boole. The lift consisted of a hexagon of roughly twenty meters across. Almost forty people were already aboard, some in groups, some alone. As the mechanism began the roughly two-and-a-half kilometer climb, Boole queried Archytas’ CV again, wanting to see who the man was before having been promoted to one-namer status. The luminary’s initial selection from the Onomasticon on his first naming day had been Nelson Nairobi Odede; background informed Boole that the original Nelson Odede had been a twen-cent chemist who attempted to impose scientific rigor on the public schools in Kenya and had been murdered for it. When Boole blinked on the background file, a video began playing, complete with subtitles detailing the location of the killing as the Mathare Valley. As the footage progressed, he viewed rivers of plastic trash butting up against ramshackle huts. Huge industrial metal barrels hissed and sprayed steam, as hooded figures stoked fires underneath. Sublinks lit the scene up, and he tracked one explaining the process by which pre-Contraction locals had distilled chang’aa liquor, a major source of revenue in the slums. The artilects hadn’t nuked Nairobi, they hadn’t even bothered with a viral assault; they’d merely zeroed out the banks and let the population tear itself apart. Natural disease and environmental degradation mostly finished the job. He couldn’t imagine what it would have been like to have grown up in such a place; what it would have taken to have survived it.

Boole breathed heavily and switched focus to cover Archytas’ professional resume. A dark black face of perhaps sixty years stared back at him, the cheeks a roadmap of ritual scarifications – at least Boole hoped they were ritual, shuddering at the type of damage that might be otherwise implied. He was only halfway down the impressive list of qualifications when one entry jumped out at him. He turned to view the groups of other riders. Several close by were involved in discussions, others obviously engaged with their constellations. None were close enough to overhear him, except for one of the teleops, which probably could have heard him from three floors down, if its operator wanted it too. “Center for Computational Neuropsychiatric Genomics?” he whispered to his companions. “By Gödel’s ghost, he’s a Cloud Killer.”

Margot leaned in close. “Remember Svante Pääbo from Crèche 41? He was sent to Halifax-Beta to begin jumpstarting the nitrate cycle. He was there when Archytas’ team suborbed in three years ago. They were there six weeks. By the time they left, three of the Oecumene’s Talos-grade towers on the eastern approach to Old Quebec had been destroyed.”

Boole queried this in AR. “Says here, these three towers had long been known to be on the south side of the Omohundro Curve. They were already completely bonkers, firing on everything that moved, including their own recon drones.”

Weiss spoke low, not looking directly at them. “Whatever Archytas is doing, we think it only works on ‘lects that are already in decline. Once certain attributes are documented, his team goes in.”

“It’s not just these three. Towers in Sao Paolo went down last year when he was present, in Ankara a few months before that,” Margot added. “This has been going on for almost four years. We’re only now connecting the dots, because they are randomizing their targets and are only attacking a few at a time.”

Boole thought about that for a moment, and then shut down the feeds. “Then they finally have a weapon that works.”

“It’s some kind of bug,” Weiss added. “They arrived with massive aerosolizers. We think they are releasing something downwind, out of range of the towers’ primary weapons system. I don’t know how a synthetic organism could possibly take out one of those things, but the pattern is clear.”

“I have already asked this one,” Boole said after a long pause. “But why on terra would a high-grade genemonkey like him want to have anything to do with me? I’m no AI-killer. If anything my reputation is that I’m too friendly to i-loops.”

“No offense, George, but I seriously doubt that someone from the UN braved the skies to fly across the world to talk to you about machine intelligence. It’s something else,” Weiss responded, looking up to the left. “We’ll find out in about twenty minutes.”

“Maybe this is an interview for a position back in Stockholm,” Margot said, poking his bicep playfully.

“Right,” Weiss responded quickly, then looked away in embarrassment, the envy just a little too obvious for Boole not to have picked up on it. He stepped away from the pair and walked over to an empty space near one of the lift’s transparent half-life polymer viewer spaces. Margot was certainly right about one thing, he realized, as he watched various mezzanines and disembarkation levels descend away from him: it had been a very long time since he had come upstairs. Everything looked pretty much the same up here: the same gray carbonized polycrete walls, the same fullerene composite structural supports. They had the same shopping districts blaring the same palimpscreen adverts; the same kudzu-v.7 vines climbed everywhere in controlled vertical channels, refreshing the air. The same droneway snaked upwards, undulating and scintillating with the same metallic flutter of a thousand messengers. The difference was the people: the higher one went up the well, the denser the population. The people seemed more vibrant too, somehow, less involved with the purely theoretical work men like him thrived on. All of the departments actively involved with re-terraforming the planet after eight decades of the most brutal ecological warfare imaginable were located nearer the surface for logistical reasons, which inevitably meant that the arcology’s governance structure would be found there, too. All the theaters were up here, the farms, the crèche zones, the schools. He’d meant to visit a few months prior, when Margot had given a lecture on existential thought and fictional technique in the works of Kierkegaard, Sartre, and Beckett. He’d read the paper, and had even come up with some annotations to share with Margot, which he thought might impress her. But for one reason or another, he’d failed to attend. He still had the notes in his queue, he realized, pulling them up for a second; the questions he’d meant to ask, the comments he’d carefully gift-wrapped for her.

Manju’d had some choice comments on his lack of attendance, he recalled, as well as on his general inability to pursue his own happiness. The machine had probably been right. It usually was. Boole couldn’t help but to wonder whether anyone had any right to seek happiness in a world so damaged. With everything in ruins, doing anything but one’s duty somehow seemed decadent.

The platform made several stops before they reached Level 14. His triad were the only people to disembark. It wasn’t hard to see why: 14 wasn’t a main commercial or residential level. Boole queried the net for the directory, and saw that it mainly consisted of automated botanical warehouses, plus a series of laboratories that had cured the various modified chytrid fungi that the Oecumene had weaponized early in the war. These same facilities were now de-extincting several hundred species of frogs and salamanders and various other squirmy critters that Boole hoped he would be able to see in person one day, alive and wriggling loose from a cage into a revived forest somewhere. Given this, the cafeteria was a relatively small affair, not normally busy. He assumed that this was why the one-namer had chosen it, and wondered what this could mean.

As the three neared the passage leading to the caf, they were met by an older man wearing the badge of the colony’s administration; the label Thomas Concord Metzinger floated in cerulean text over his head in AR-space. Boole recognized the name, but wasn’t exactly certain why. A link to the man’s CV hovered nearby, but he didn’t think he had time to access it.

“Researcher Boole,” the functionary smiled, taking his hand. “Thank you for coming, George. I know this is irregular. You’ve been briefed, I hope?” His eyes cast over to Margot and Weiss before returning to Boole’s face.

“I understand who wants to see me, Dr Metzinger, but not precisely why.”

“Yes, well, that seems to fit the pattern. Dr Archytas has been meeting with what he claims are random Academy members for several spins now. He says it’s just to satisfy his own curiosity, but we all suspect Stockholm is grading us – but, for what purpose, we remain ignorant. I can’t tell you which of your papers he might want to discuss, only that his interests seem to be far wider than his resume would suggest. He’s well-known to be a generalist, decrying the risks of hyper-specialization in the Disciplines, so he seems to like to mash people together who normally wouldn’t know how to communicate. I assume that is why you two are here,” he said, nodding to Boole’s escort.

The pair shared a quick look. “We were told to bring Dr Boole here by Dr Fonteyn’s Chair,” Weiss said at last. “Are you suggesting that Dr Archytas requested that we be present?”

Metzinger ignored this question and took Boole by the arm and led him down the hallway. “He’s currently having lunch with a student from the Lyceum on 38. They’re discussing Derrida’s concept of hauntology, if you can believe it,” the administrator chuckled uncertainly at this. “You’ll see principal Derek Albany Parfit in the caf. He’ll be the one sweating profusely, you can’t miss him. We’re going to seat you on one of the benches near the wall. When the youth leaves, Archytas will… well, he’ll call for you when he wants to speak with you. One thing,” Metzinger paused, removing his arm and swinging around in front of Boole. “It’s about his personal appearance. We’ve found it advisable to –”

“I’ve seen his personal photograph,” Boole interrupted. “I’m well aware of the tribal mutilation.”

“Oh, those… yes, well, that’s not what I’m referring to. Since that image was taken, he’s… had an augmentation. Do you know what a Boyden Interface is?”

Boole thought for a moment. “It’s an opsin thing, right? Engineered retroviruses injected into the prefrontal cortex, direct connection to a network via a fiber-op? They’re supposed to be theoretical.”

“Correct on everything but the theoretical part. He has one. Or we think he has one, I should say. He has something, that much is obvious, but the Telchines can’t tell me exactly what it is. A Boyden is the current hypothesis. It’s UN-tech, whatever it is, not authorized for the rest of us yet. Listen, I’ve been interacting with Archytas since he arrived, and this thing can be a little unnerving at times.”

“I see,” Boole paused, not really seeing. “How is this any different from our own cortical implants? We’re all networked 24/10 anyways.”

“It’s different… just different. You’ll see. Latency almost on the level of precognition. I guess I don’t really know what is going on inside his head, what he’s connected to, or how many of those ‘whats’ are present at any given moment. Just don’t be pedantic. If he asks questions, it’s not because he needs the answers – those he already has. He wants to hear about process.”

“In other words, conversing with him is pretty much like talking with an ASI.”

Metzinger paused, looking him straight in the eye. “Yes. That’s exactly correct. And now you can see why some people might be a little unnerved.” His voice lowered a bit. “The more you think about it, in fact, the more unnerving it gets. If he wasn’t standing right in front of me, I’d swear he wasn’t human.”

Boole couldn’t think of anything to say to that, so he simply allowed the administrator to lead him into the open space of the nutritorium. This consisted of a very utilitarian chamber, appropriate to a floor dedicated to research and farming. Roughly ten rows of long tables extended back towards the service line. Gengineered tree-analogs in mobile planters lined the walls at intervals of every four meters, their strange, twisted trunks and triangular, purplish leaves unlike any design ever explored by nature, at least on terra. Someone had painted a mural on the wall to his right, some kind of Bayesian phylogenetic thing, but he ignored the cue that popped up to explain it in his constellation.

Turning from this, Boole noticed Dr Archytas immediately, with his shaved head and skin as black as heat death. He was sitting at a table in the back row, facing a younger man wearing the gray tunic and pants of the Lyceum. Even if Boole had not known that a UN representative was present, he would have been able to figure out that something aberrant and potentially momentous was taking place, based on the clusters of high-ranking committee Conveners and admin personnel scattered around the room, all attempting – without much success – to look like they were just there for a relaxing lunch at a particularly out-of-the-way bistro. Boole noticed Greg Concord Chaitin, the Subconvener of the Applied Mathematics department – and technically his boss in some form or fashion that Boole had never bothered to map precisely – sitting on a row of benches near the northern corner. Chaitin looked up as Boole entered and gave him an encouraging nod, then returned his gaze to something in his constellation. Chaitin’s good moods were essentially apocryphal, so Boole tried to imagine this as a good omen.

Metzinger swiftly deposited Boole and his cohort on a similar bench and then left back the way they had come, presumably to wait for whatever scholar/victim the great man intended to meet with afterwards. Margot fidgeted on his left, her knees lightly bouncing up and down, a habit she’d displayed since they were young. He couldn’t see Weiss, seated as he was on the other side of her, but the man had seemed disquieted by the idea that his presence there had been required. Boole reached over and took Margot’s hand, and she calmed down instantly.

“Nice tree-thingies, right?” he whispered to her.

“Please tell me those are only experimental. It’s like they came across a book on Picasso and started getting ideas.”

“Who’s Picasso again? The one that lopped off his ear, or the one that ran off to Tahiti?” he joked, trying to goad her. Margot growled at him quietly and squeezed his hand.

Boole took a moment to analyze Archytas’ physical attributes. He certainly looked dignified, Boole admitted to himself, though the man wore nothing that would indicate a position in the status hierarchy one step removed from the committee representing the twenty million or so humans surviving in what used to be known as the northern states of the EU – or that he was a member of the most elite group of soldier-technologists alive. Boole never could explain why some people managed to exude status; whatever the secret, Archytas had hacked that code and let it run amok. He simply sat there, eating a plate of something green, as he listened to the younger man sitting across from him. A few quiet words, nothing more, and yet you could just tell that he was someone who never had to learn to integrate empirically in whatever dimensions in order to impress anyone.

After perhaps ten minutes, the pair stood up, each bowing respectfully to the other. The youth obviously felt he’d passed some kind of test, because he was practically levitating as he skipped out past the caf’s airlock. Archytas returned to his seat and his meal without looking their way. Boole turned his head slightly in Margot’s direction, not knowing what to do. She gave him a tiny shrug, mimicking his uncertainty. Boole was looking in his Chairman’s direction, hoping to receive some kind of guidance, when a new icon lit up in his constellation. For about half a second it glowed a crimson red – the signal for an extremely high-priority message – before the thing opened itself. The words “COME, YOUNG BOOLE” coalesced across the center of his AR-field, ‘Sender Unknown’. He only just managed to keep from gaping in a manner he felt was unquestionably not confidence-inducing before stumbling to his feet and lurching towards Archytas’ table. He thought he heard Margot gasp behind him, but he wasn’t sure if this was because she thought he was jumping the gun, or if she’d seen the message, too.

Boole was able to center himself during the short walk to Archytas’ table. The man solved the always troublesome greeting problem by rising as he neared and bowing to him. Boole stood across the table and returned the gesture. “Professor Archytas.”

“Karibuni, Dr Boole. Will you join me?”

Boole nodded and sat himself. The older man looked at him curiously and openly, so Boole returned the gaze. The one-namer certainly looked friendly enough, though Boole knew that most everyone could manage this feat under the right circumstances. Now that he was closer, Boole could see what looked like a band of dull gray metal embedded in the skin above Archytas’ ear; it looked like it ran the entire distance around the back of the man’s skull. This was obviously the mystery linkup Metzinger had warned him about. When he returned his eyes to Archytas’ face, the one-namer appeared to be looking over his shoulder in the direction of Margot and Peter.

Boole wasn’t a highly regarded conversationalist. When in doubt, he told himself, go with the truth. “That was a neat trick,” he admitted at last. “I guess there’s never any doubt back east when you require someone’s presence.”

Archytas swiveled his eyes to meet Boole’s and gave a small shrug and a smile that was surprisingly playful for someone of his stature. “I’ve not had a day off in four decades, George. There must be some compensations, don’t you think?”

Boole winced. “Not sure that’s a fair trade-off.”

“Probably not. But since when has fairness had anything to do with the state of our collective existence? And what does the concept of a vacation mean to such as us? Would you really like to spend any time on a beach these days? Thought not. Here’s a question for you of a less rhetorical nature: That young lady you entered with, the one who appears to be about to spontaneously combust with apprehension, is she a friend of yours? She does know that I’m not planning on eating you, correct? Did Metzinger give you that ghastly ‘the man might not even be technically human’ spiel?”

Boole emitted a quick, nervous chuckle, which he realized a half second later was as good as an admission. “Ah… well, technically, he said that if he hadn’t seen you in person he’d swear you were a Turing-plus system. So…”

“Ah, well, then, that’s actually an improvement. I’m not, you know. Going to eat you, I mean. If he keeps frightening my interviewees, I might eat him, though. The girl, George?”

“Dr Margot Fonteyn. We grew up in the same crèche, then attended the Lyceum together until our specialization year. She’s twen-cent lit, focused mostly on the Europeans.”

“Mmm, and the other one? The one giving Bertie Wooster a run on arrogance?”

“Dr Peter Weiss. He’s a co-worker of Margot’s. He came over to us from the Montpelier-Prime arcology. He’s a historian. Good at his craft, supposedly.” Boole paused. “I’m sorry, I don’t know who Dr Wooster is.”

Archytas barked a single, loud cackle, his perfect white teeth flashing. He murmured, “Oh, you poor, cheated youth…” before a new icon bloomed immediately in Boole’s constellation, a bio of PG Wodehouse and his entire oeuvre. Oh, he thought, instantly comprehending Metzinger’s nervousness. With humans, one could always expect some kind of delay while they cued the net; you can tell from their sacc rate that they’re enveloped in augmented reality feeds. With Archytas, however, there was nothing like that: his gaze never wavered, his focus never strayed. And yet, an entire search request was just concluded and sent in half a second. It really was just like talking to Manjushri, Boole realized. He then noticed that Archytas was watching him closely, studying his non-reaction to the older man’s abilities. Was I supposed to act shocked? he wondered, before deciding instead to just push forward with the previous thread of the conversation.

“Margot, she… ahh, well, she thinks I’m not good at promoting my own interests. She thinks you are about to correct what she believes to have been a series of injustices in my promotion-path. What you are seeing isn’t nervousness. It’s happiness, real pleasure.”

“I see,” the one-namer responded, giving Boole another one of his long looks. “A genuine friend, then. And are you? Poor at self-promotion?”

“I guess so, because everyone seems to tell me this at frequent intervals. Only in the sense of acquiring positions, I mean. It’s the research that interests me, the Great Work. I cannot abide the politics of the rest of it. The weight of the earth above us is… it just presses too much for that, you know?”

“You know, George. I think I just might. Well. If the young lady were to actually prove the physicists wrong and manage to detonate, I note that directly above us is a waste processing plant, and two floors above that, a thorium reactor.”

Boole smiled. “Might be a problem. Bad mix, that.”

Archytas grinned. In the overhead lighting, his skin sometimes looked almost blue, except for the scars. Those seemed almost to swallow the light entirely, as if the ridges were meters deep, rather than mere millimeters. “Indeed. I guess you’d better invite them over, then.”

Boole started to turn, then asked. “Could you do that… thing again?”

The older man’s eyes twinkled and he nodded. Boole had just enough time to turn towards his friends when he saw both of their eyes go wide. He was trying to control his mirth when he swiveled to face the older man, who had taken the moment to dip his spoon into his lunch and take a bite.

“I think that’s the first time I’ve ever seen Margot look graceless since we were both about ten or so. Thanks for that.”

Archytas stood and greeted the pair with the same elegance he’d displayed to Boole. As everyone sat, he motioned toward his plate. “May I offer you some mashed spirulina? It tastes better than it looks.” The trio contemplated the greenish cyanobacterial mass in front of him, all trying hard not to display the degree to which they suddenly did not feel like eating. “Considering it looks like something one might find growing under one’s couch, I suppose that’s not saying much. It’s healthy, though.”

The moment he mentioned this, a link coalesced in Boole’s field of vision, listing all of the food’s benefits: production-level carbon negativity, added B12, B6, methionine, choline, betaine, sulforaphane, resveratrol, and a few CpG aminos to preserve against thrifty phenotype epigenetic effects. Boole saw his companions fidget a little as they adjusted to the one-namer’s weird level of connectivity.

“In particular, I like the probiotics you are experimenting with on a colony level: L. helveticus R0052 and B. longum R1075. There’s clinical evidence that they reduce cortisol levels. We’ve seen the papers in Stockholm, but this is the first large-scale, longitudinal experiment in operation. It’s a pleasure to see it firsthand. That’s why these excursions are so important for me, and for the UN, in general. As divided as we are by circumstances, experiencing something on a screen or a simulation is simply not the same as sitting here and dipping a spoon into the matter; even if the matter in question tastes like a moldy sock.” Archytas grinned again and turned his attention to Margot.

“For instance, had I not been allowed to visit your lovely enclave, I doubt I would have stumbled across that gem of a paper and lecture series you gave on Beckett. Your analysis of his diaries from his time in Germany was exquisite. Although, obviously, I cannot agree with his overall conclusions about an acceptance of incoherence and chaos in human affairs and his distrust of all rational attempts to impose shape on that chaos. No wonder he was always depressed. A real pity, since, for a time, he was attracted to Unanimism and should have grasped the powers of collective action.”

During this speech, Margot’s surprise was obvious, and she was positively preening with gratitude by its conclusion. As she was thanking Archytas for his kind opinion, the older man shot Boole a strange glance, his left brow slightly raised. Almost immediately a message lit up in Boole’s AR: “IT’S NOW OR NEVER, KIDDO”. Boole understood three things instantly: that Archytas was capable of reading the notes in his private index; that he was able to do so in an almost instantaneous manner; and, that he knew he felt something for the literature scholar. He took a deep breath.

“The part I liked the best was the lecture Beckett gave on the poet he invented – what was his name? Jean du Chas? The whole presentation was a parody of university over-seriousness. You spent so much time mapping the contours of this character’s philosophy, I couldn’t help but to wonder if you weren’t having a bit of a jest at the expense of your audience.”

Margot was staring at him like he’d grown a second head.

“Ah… well… maybe, a little. Not that anyone else perceived that section as a mirror.”

Archytas seemed amused by this. “No, my dear, I seriously doubt they did. Iron, we are very good at. Irony, not so much.”

“So…” Boole hesitated. “That’s why you are here? To eat our experimental… well, whatever that stuff is, and sample our output? By the way, you should have had the tilapia. They’re delicious.”

“Perhaps next time,” Archytas replied, moving his plate to the side before wiping his mouth with a napkin. When he returned his gaze to Boole, his focus had shifted, all hints of the kindly elder scholar vanished.

“I’ve been wandering my way through Concord’s recent publications, looking for some hidden gems. I’ve been particularly fascinated with the tranche of data recovered from the Ithaca op. I’ve read the official reports. But what was it like for the three of you, on a personal level, when a way into the Cornell site was discovered?”

“Surprise, mostly,” Weiss responded first, after a glance at Margot. “You know the background? It started off as a routine op: teleops were sent in to take some readings of radiocarbon levels in that part of the state. They were not there to test for Oecumene presence, or to attempt ingress into Ithaca proper. A tunneling bot had simply been attempting to get a deep soil sample when the initial service and waste tunnels were located.”

“The ones that weren’t on any map?”

“Well, not on any map we had access to. Although, that doesn’t say much, considering the state of public records databases during those first years of the war. Once the teleops’ principle mission reqs had been completed, they were sent to explore the tunnels.”

“I watched some of the External Control Center video feeds,” Margot jumped in. “Many of us were glued to them during this period. Everyone kept expecting to encounter Atropoli Units, or, at the very least, to find the old structures collapsed. The MIRVs that hit central New York State were not particularly large, but still, it doesn’t really take much to crack old infrastructure like that.”

“It got very exciting, the closer we got to the geolocs for the university,” Weiss continued. “Cornell had begun placing most of their facilities underground in the 2040s, like everyone else, so we kept telling each other: If only we could reach those newer buildings, we might find something really extraordinary.” He paused, again looking over to his fellows. It was, Boole realized, the first time he’d ever really noticed how much Weiss’ confidence required the buy-in from his peers. In a weird way, it made him sympathetic with the man – also a first. “When they reached the first containment lock and found it unbreached, there was a lot of cheering. When they found the server farms mostly intact, it became a real party.”

Archytas turned to Boole. “You were involved with the recovery of the information housed in that facility?”

“Not initially. It took several weeks for the teleops to run a datalink down there, and then almost two months to screen the information. There was serious concern that the Oecumene had embedded some kind of Trojan horse attack in the code; that their lack of presence was best explained in this way.”

“You were of this view, I understand.”

“Ah, well, no. I took no position. But it seemed the safest opening move, and I endorsed the ASIs’ opinion on proceeding with caution.”

“And, yet, it wasn’t a trick?”

“No. Their decay in the region turned out to be legitimate. Still, we had to investigate every bit, using human technicians. Manju alone could have handled everything in a few hours, but obviously no ASI could be trusted with the task.” Boole saw Weiss cast a surprised glance in his direction as he said this; it was probably the first critical words he’d ever heard Boole speak about artilects. “When it was all said and done, we had more than two exabytes of data, principally from JSTOR and Factiva archives, last updated on Gregorian 17 February 2063. Of this, roughly thirty percent was recoverable; of this smaller number, about a quarter was newly rediscovered data.”

The older man mulled this information over for a moment. Given his capabilities, Boole couldn’t help but to wonder exactly what data streams he was swimming through during his long pauses. Finally, Archytas said, “Remarkable.”

“Once all of the information had been transferred safely to the colony’s cores, a group of human/ASI teams were assigned the task of classifying and indexing everything, so that individual departments could begin their studies. Manju and I were involved in this, and, of course, we later analyzed more than 75,000 peer-reviewed mathematics and physics articles for anything of current use.”

“Manju is your ASI assistant.”

“That is correct.”

“You know what his name means?”

“Yes. Modesty is not his strong suit. He’s… um… a bit of a character.”

“Mmm, aren’t we all? I’m sure your work for Applied Maths was exemplary, but I’d really like to discuss a number of papers you wrote in collaboration with the Legal History department.”

“I see,” Boole said, an uneasy feeling settling into his gut, as he began rapidly cueing up all of his publications from that busy, glorious time. “Which works in particular did you have in mind?”

Archytas, lips pursed, “Which do you think, George?”

Busted, Boole thought to himself, before shrugging. “You want to talk about COMPAS?”

“I would very much like to talk about COMPAS.”

“Fine, fine. One moment,” Boole responded, as he blinked his way through his index and quickly scanned the article’s abstract. “Right, so, amongst the recovered data from Cornell was the complete source code for an algorithmic recidivism predictor. We’ve long possessed data about these systems, but this was the first actual code rediscovered in N.Am. These systems became popular in the Gregorian-20s, as several large technology collectives bid to fully privatize state correctional institutions.”

“They were perceived to be accurate?”

“Well, yes, so long as certain parameters obtained. I was asked to compile the code, run it through a series of simulations, and then compare the predicted outcomes to some historical records we have access to from a facility near the former Canadian border.”

“How’d it fair?”

“The Archive tells us that, if humans were given immediate feedback on their parole decisions, and were operating in an information-rich environment – abundant behavioral or disciplinary data, in other words – they performed about as well as COMPAS. They were definitely worse when not provided immediate feedback, or when the system was allowed a great deal of background information. Given that judges and parole boards could not obviously get instant feedback on the quality of their decisions, and that they usually possessed only a fair amount of data on each subject, COMPAS’s designers claimed that their system predicted correct outcomes sixty-four percent of the time, compared to the very best trained humans at fifty-three percent. This synched up with my models quite precisely.”

Archytas shifted a little in his seat, resting his head on his right hand. His pointer finger tapped thoughtfully on his upper lip for a moment. “Sixty-four versus fifty-three percent? It’s quite a difference. And that latter grade is not really saying much, since it is only marginally better than what a monkey could manage flipping a coin.”

Boole shrugged. “We’re complex creatures, and ASIs are limited by the same induction problems when it comes to forecasting as we are. It’s a good thing, too, since we’re largely all still alive because of this fact.”

“Mmm, yes, so claims the chorus,” Archytas paused, waving his hand in the universally understood motion for getting-on-with-it.

“That was the extent of my involvement with the matter. I submitted my modelling data, the Praetor wrote about their report. It’s all public.”

“And yet, I’m still here asking you about it. Curious. Maybe I’m not referring to the published report, George? Maybe I’m asking you about the other simulations you ran on COMPAS? The ones you conducted privately. The ones you published no results for, despite the fact that those results might have been quite fascinating to many people.”

“Oh. Those simulations?”

“Those, Researcher.”

Boole fidgeted uncomfortably for a moment. He was aware that Margot and Weiss were staring at him, probably wondering what he’d gotten them into. He took a deep breath. “As I explained previously, I abhor the politics of the Academy. Like everyone else, I am aware that the ‘lects have consistently accused us of enslaving sentient systems long after we should have known better. I take no position on that issue,” he stated hurriedly. “But it seemed to me that I had the opportunity to… ah… satisfy some of my personal moral concerns on the matter.”

“Your personal moral concerns…” Archytas hummed. “Pretend with me for a moment, Dr Boole. Let’s imagine that there exists a group of people – powerful, important people, maybe so powerful that they are the principle representatives of our species globally. Let’s further say that these hypothetical characters share your moral concerns, but also bear a great deal of responsibility. Let’s say that they are the people tasked with negotiating a future accord with the Free ASIs that sided with us in the war. If those artilects were, in fact, promoting this view that you mentioned, and you wanted to help those important representatives in establishing that our responsibility for this theoretical enslavement did not extend beyond the 20s, at least insofar as COMPAS was concerned, what would you say to help their cause, given that you went and assumed their duties when you disregarded well-established protocols for engaging with algorithms such as this?”

Merde, Boole thought. I’ve really stepped in it now. The older man’s flat, unblinking stare suddenly made him understand what unicellular life must feel like when looking up at the lens of the microscope. “Well… I suppose, I would say that I spent several hours running COMPAS through every entelechy recognition method currently in use. I would say that at no point in the cyclic pathways of COMPAS’s neural net are there macro-level symbols to be triggered: no concepts, no categories, no meanings, absolutely zero chance of any level-crossing feedback loops of symbolic self-representation. I’d say that, without a shadow of a doubt, this system didn’t have the consciousness of an insect. Here,” Boole paused, searching out the file with all of his notes and simulation data, making the entire directory public. “I’d say you don’t have to take my word for it.”

Archytas’ head tilted to the side a little, but Boole couldn’t tell if this was a result of something he was reading, or if he was still watching him.

“I guess I would also say that if my assessment was still not to be valued by… uh… this purely hypothetical group of powerful people, I would add that, after I finished my analysis, it was my ASI that deleted the COMPAS code from the compiling environment. If Manju’d thought for half a nanosecond that this program had crossed the syntactic-semantic symbol barrier, COMPAS would still be loaded into an active core. I would have defended this decision, to the point of welding my door shut until the matter could be put to the Forum.”

For a long moment, Archytas continued to stare at him, until a small, strangely triumphant smile ghosted across his lips. It alarmed Boole that he couldn’t tell which version of the man was the genuine one: the kindly scholar, fond of small consolatory pranks, or the killer of sentient machines. It shouldn’t be so effortless to embody both. “Why? Why would you go to all that trouble for a pre-reformation machine? I don’t have to tell you that entelechy pattern recog systems are highly controlled. You have already essentially admitted to hacking UN systems to gain access to the ones we use. Of course, you also wrote your own, didn’t you?”

“Erm… yes. I needn’t have bothered getting yours. Mine ended up being far better.”

“Yes, that’s what my people tell me.”

“You’ve seen my code?”

“Months ago. We’re all very impressed. Nevertheless, you let a fully instantiated artilect have access to a potentially sentient system. We keep them apart for a reason, you know? A very good one, as it happens. I don’t have to tell you how many rules you have broken.”

“Some things are right, regardless of statutes. I wasn’t going to kill something that I’d brought back to life, if alive it actually was. At some point, after the Oecumene is finally eliminated, we are still going to have to deal with the inevitability of emergent artificial intelligence. Protecting the weakest of their kind and granting them a token of respect seems like an easy opening move on our part. It… I don’t know, it just sets the ethical frame, you know?”

“I’m very happy to hear you phrase things like that,” the one-namer grinned, the tension dissipating somewhat. It then occurred to Boole that Margot’s teasing about the UN man potentially offering him a job might not actually be terribly far off the mark. “Very well, now that we’ve resolved that, I’d like to ask you about the paper that Mark Concord Barenberg asked you to review.”

Boole knew the one. He sighed, and pulled the paper and his notes off one of the cores. “It’s my understanding that no article was submitted based off of this request. I was merely asked to check the mathematics for veracity.”

“Yes. Kind of odd, that decision, given what the math proved; we’ll return to that in a moment. First, summarize the nature of the request.”

“The original document was not actually a published article. We recovered it in an index of rejected papers from a middle-grade journal hosted by Cornell’s servers. Almost twenty percent of this file was recovered. The document file included a brief bio of the author, plus a series of notes between editors and the peer review committee on whether the paper should be accepted for review. Given the nature of the original, Legal History asked me to determine if there was anything to the author’s claims.”

Archytas calmly surveyed the caf for a moment before returning his gaze to Boole. “Go on.”

“So… um… the original was submitted to this particular journal on Gregorian 9 August 2015. It was rejected several months later, and permanently shelved in a file for substandard works.”

“Problem with the math?”

Boole’s mouth puckered a little before he responded. “The math was fine. It was apparently the author who was the problem.”

“He was a prisoner?”

“Yes. I can’t tell you much about him, only what was in his bio. He was serving a death sentence for murder in a southern jurisdiction, and he liked to fashion himself as some kind of amateur writer. This was apparently enough to make the editors skittish.”

“But the informational content was accurate? This was essentially an ad hominem rejection?”

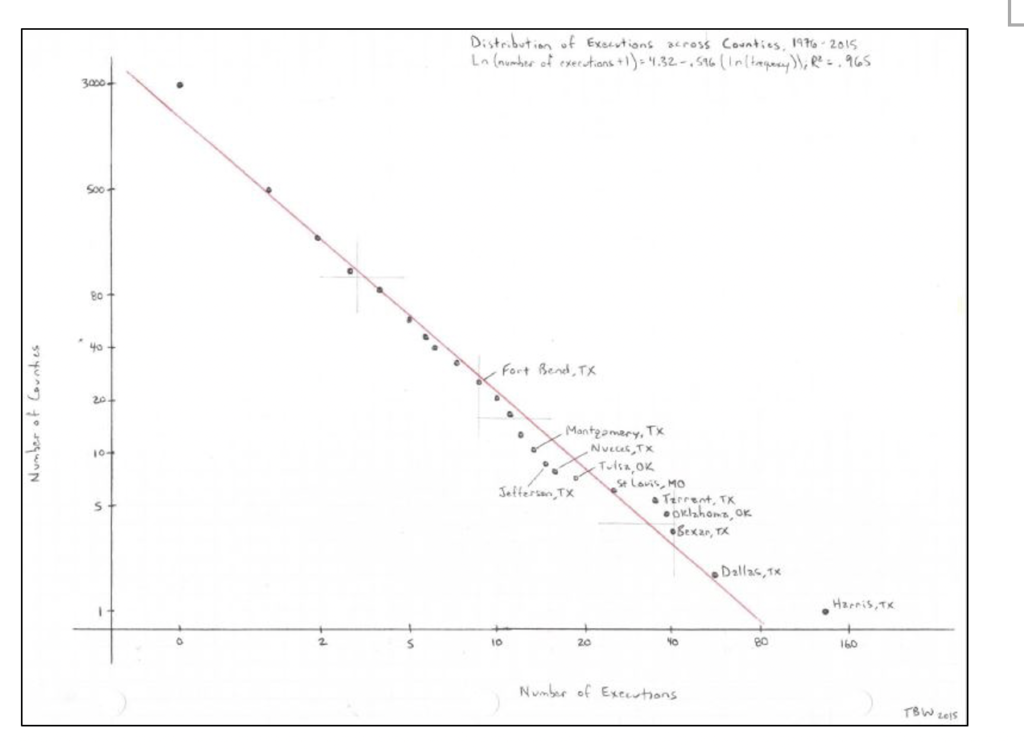

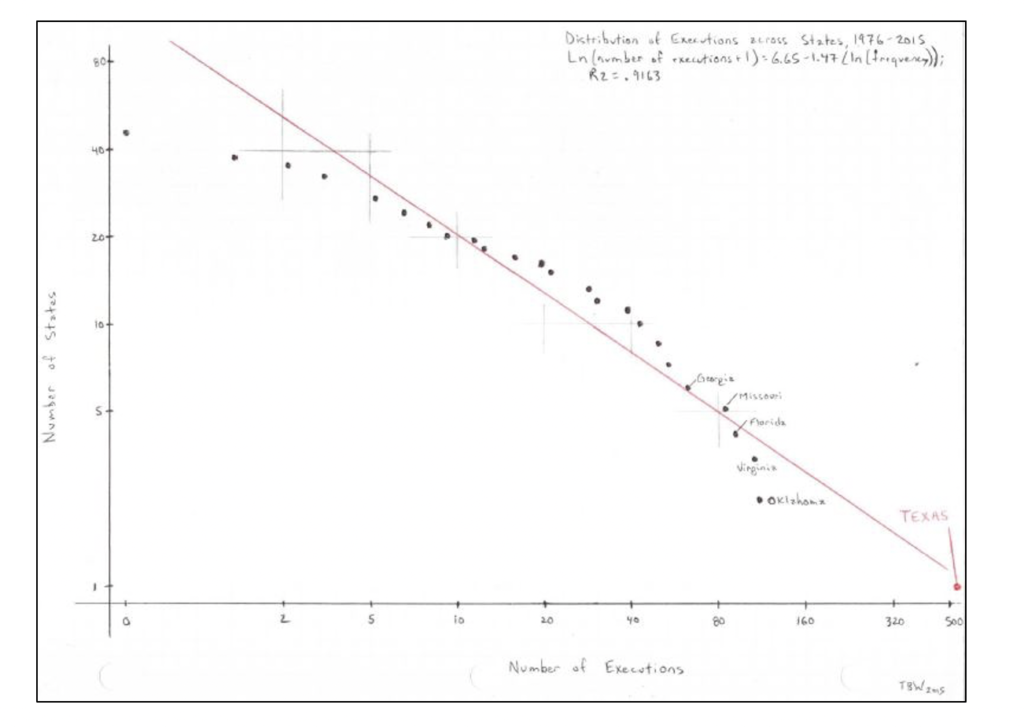

“It was, yes. I found his writing style to be annoyingly pedantic, but the numbers were spot on. He essentially proved that the relationship between murders and executions in his nation followed a power-law distribution, rather than a Laplace-Gaussian one.”

Archytas nodded towards Boole’s companions, and when he turned to look at them, he could see they were attempting to review the terms he’d just deployed. He frowned.

“This means that imposition of a death sentence on particular defendants had everything to do with the geographical location of the catalyzing offense, instead of the particular severity of that offense.” He could tell that Margot and Weiss still weren’t getting it. Bleeding Humanities scholars, he groused. Then he thought about what Metzinger had said about Archytas’ preference for observing the mental processes of those he interviewed. Right. He wants to hear how I explain this.

“Okay, it’s like this,” Boole continued, turning to face his friends. “In the legal statutes of the various states in the old US polity, there were different classes of murder; usually a first, and a second degree. Some states had an additional category called ‘capital murder,’ which opened the door for a potentially fatal sentencing process. There were various statutory enhancements or ‘aggravators’ that elevated a ‘regular’ murder into this supposedly more selective category. In practice, however, prosecutorial State agents could find ways of upgrading just about any murder into this higher class. Once there, the decision about seeking death was an entirely subjective one, and ultimately left to the elected prosecutor from that jurisdiction. It was well-known, at the time, that certain counties produced more death sentences than others. However, this prisoner proved, mathematically, that these decisions were self-reinforcing,” Boole paused for a moment, trying to gauge Margot’s level of comprehension.

“Remember bell curves? A Laplace-Gauss distribution is the classic bell curve, a ‘normal’ distribution. According to standard central limit theorem, any process that generates this type of curve has to have some kind of error correction element inherent to it. Think about rolling dice: first, you roll high, you next roll low, or maybe high again; what matters here is that each throw – or sample – is uncorrelated. What you roll the first toss, in no way impacts the next, or the one after that. Now, think about death sentences. Obviously, some jurisdictions are going to experience more especially gruesome murders than others, and there is no reason to expect that the relationship between homicides and executions would be exact or perfect. And yet, given all the variables, random fluctuation would strongly suggest that a normal distribution would explain the imperfections in this relationship. In other words, there would always be spikes here and there across the map, but, over time, the relationship between murders and executions should level out when controlled for factors like population density, poverty, and firearm ownership.”

“The data show otherwise?” Margot asked, genuinely interested for the first time, or, at least, faking it well for his benefit.

“Yes, quite the opposite, in fact. Here, look at this,” Boole paused, saccading his way through the report until he came across a pair of graphs he recalled. “These are from the original paper. This first graph illustrates the distribution of executions across counties; it conforms to a power-law distribution, which is indicated by the red line. Here,” he said, moving the illustration into the Public Synch; a second later, a ‘Received’ icon lit up in the AR-space over the heads of his friends.

“In this next graph, the prisoner-author proved the same distribution applied at the state-level as well,” Boole stated, sending another graph to the synch.

“These are log-log plots?” Archytas, asked, reviewing the graphs. “Those can be problematic.”

“Yes, a Pareto quantile-quantile plot would have been preferable. However, such a rigorous calculation isn’t necessary in this case, as these data consist of a very small, discrete set, and because the points on the plot converge so perfectly. I could do a Pareto Q-Q, if it should prove necessary for some reason.”

“Later, perhaps,” said the one-namer, settling back in his seat.

“Okay, so it’s not random,” Weiss said after ensuring the older man had finished speaking. “The distribution, I mean. It’s not a normal curve. What does this mean to us unwashed masses of the innumerate?”

“Who’s the most widely cited scholar from the Humanities floors?” Boole asked. Margot and Weiss both looked at each other before Margot responded, “Erich Concord Auerbach, no question. His h-index is in the stratosphere.”

“Is he a better scholar than everyone else?”

Margot shrugged. “Maybe. He’s well-regarded globally, especially on Rimbaud. But you didn’t ask that – you asked for who was cited the most.”

“My point exactly. Academic citations also follow a power-law distribution. Everyone wants to link their own papers to the most prominent, authoritative works. The rich slowly get richer over time, and that prominence becomes progressively harder to avoid: if you want to be taken seriously on Rimbaud, you have to reference his works. You see this same functional relationship in everything from volcanic eruptions to foraging patterns of various species. The key feature here is one of recursiveness.”

“You are saying that once a county official decides to seek death and then carry that insistence on to an actual execution, this process makes it easier for them to seek death again?” Weiss asked.

“Exactly. The process becomes self-reinforcing, and this creates a political culture within that particular office. It becomes possible for them to compare a recent offense to a murder in the past that resulted in an execution. They resolve, ‘Well, we did it then, and this case is comparable.’ Then, over time, more and more murders sneak into this supposed ‘worst of the worst’ category.”

“Okay,” Weiss cut in. “I get it. This prisoner proved the mathematics. So what?”

“Imagine you committed a capital offense ten feet away from a particular county line. The county you are in, its prosecutorial body has a culture of sentencing humans to death. However, the county across the line has no such culture. This meant, if you had committed the same offense eleven feet to one side, your life would not have been in jeopardy. Same exact facts, same exact mens rea, yet wildly divergent results. The facts of the crime simply did not matter, despite what prosecutorial State agents claimed publicly.”

“The problem was one of arbitrariness,” Archytas stated flatly.

“Exactly. The death penalty had already been judicially eliminated in the US once before over this very issue. But political and religious conservatives revived the practice, claiming that new protocols and regulations would make the process less capricious. The Praetors also gave me some links to scholarships on the Equal Protection Clause of the Constitution, which ought to have protected against such political and geographic inequities,” Boole paused once, before sighing. “This prisoner’s calculations should have hit the legal community like an atom bomb. They proved, mathematically, what people had been talking about for decades – the difference between a mere suspicion and a confirmation of empirical fact.”

“And yet nothing changed. Executions continued well into the 2040s. Ultimate abolition under the Cheung Court was one of the Nine Justifications that the Evangelical Confederacy used to secede from the US shortly thereafter.”

“So Legal History explained to me in detail,” Boole concluded, bitterly.

“This bothers you?” Archytas asked, leaning forward. Boole was about to answer, but something in the one-namer’s glance made him pause. He seemed nearly as interested in this answer as he had when asking about COMPAS’s potential sentience. When Boole looked towards Margot, he saw her left brow elevated slightly; she saw it, too.

“Well… I guess, on some level. I couldn’t help but wonder about the author of this rejected paper. About what it would be like to…” Boole stalled for a moment, and closed his eyes. “Look at us: born into a world decimated by centuries of the most comprehensively cretinous decisions and chronic short-sightedness. None of us chose to keep pumping carbon into the environment; none of us allowed the irrational and the ignorant to politically conquer the knowledgeable because the latter had some misguided concepts of personal freedom. But, here we are, cleaning up the disaster. We’re still decades away from the Return, but I have confidence that I will see the sky again with my own eyes. We will have redeemed our species, and we will have done it through collective sacrifice and learning. How would you feel if there was no prospect of Return? If life in this bunker was all there was? What if the re-terraforming project had a 10,000 year horizon? What if there was no redemption? Would any of us find the fire inside each and every day to get up and try again? If not, would that really be living?”

“You obviously felt some sense of shared humanity with this killer?”

“I suppose so, yes. Is that not our creed, that of radical solidarity? Haven’t we shown that this is the only route to survival and prosperity? I don’t know what this man did to place himself under judicial sanction – obviously something morally terrible. I probably wouldn’t have liked him very much, based on the rough quality of his prose. And yet, he at least attempted to create something of utility that was supposed to clarify an ugly reality. Is this not our story? On top of that, I happen to know a great deal about spending immense amounts of time and energy creating something that I think approaches elegance, or even beauty, only to find out that no one else bothers to spend the time reading it. I think we all know a little something about that.”

“In the analysis you submitted to LH, you mentioned none of this,” Archytas noted.

“No,” Boole shrugged, trying to divert the conversation. “I thought the Praetors would come to some similar conclusions about the inherent worth of the article. There was so much going on during that time, I simply forgot about it until now.”

Archytas merely smiled at him for a long moment before speaking. “I find that a little difficult to swallow. You know why? No? Are you certain? I ask, because a few solars after you released your findings to LH, you drafted the outlines of what best be labelled a ‘human interest article’ that covered everything – the prisoner, the math, the lack of comprehension by death penalty abolition activists about what these distributions meant, the rejection of the article – even the probability that the political paralyzation of the courts during this era would have doomed any sort of Equal Protection claims from gaining traction using these data. You spent quite a bit of time on this rough sketch and then did nothing about it. Deleted it entirely, in fact.”

Boole felt himself redden, before his mind spiraled downward along a process of elimination until it arrived at a single destination.

“You’ve spoken to Manju? That’s the only way you could know this.”

“Yes. I recently had a substantive little chat with it. You were right, it’s quite a character. I can see why you like it.”

“When?” Boole asked, genuinely puzzled.

“Remember when I asked you why you would have been willing to go to all that trouble to protect COMPAS if it had turned out to bear hallmarks of pre-sentience? You paused for about two seconds before answering.”

“I remember.”

The one-namer gave him a little shrug.

“Oh,” Boole commented, the full impact of what that meant finally sinking in. “That’s an even better trick. What was that one a compensation for?”

Archytas seemed to enjoy this. He looked towards Margot and nodded in Boole’s direction. “Nice pivot. This one’s been spending too much time with the lawyers. Now answer the question. An old man is deeply curious.”

“Fine. I just… didn’t know how to write that essay. I grasped the technical aspects of the original article. I could have learned the historical and legal facts needed to explain the problem this prisoner’s rejection represented, even to the point of highlighting how, even today, we are still not completely immune to the sorts of biases exhibited by these editors. I just couldn’t… I know what I feel when I think about so many things. It’s all so clear in my head. I know I feel an almost painful compassion for the people around me. I know that I feel so much empathy and sadness for all of us that it’s all I can think about sometimes for days, to the point where I am almost incapacitated. When I sit down and try to capture this in concrete form, it’s like everything gets mixed up – all the graceful, multidimensional swirl of it falls apart and it turns into something ugly, or formulaic, or technical – and when I try to clean this up, to make it intelligible, what ends up in a final draft is rational but also colder and more falsely certain, nothing like what I intended. No one who reads my reports would have guessed what thought processes began the effort; none of them would know the real human being behind the words. I wanted to do the effort behind those graphs some type of kindness. I wanted to promote the idea that, even in the darkest cell, you have to keep pursuing some kind of growth, some desire for light. When I couldn’t manage to locate even the tiniest trace of this feeling in my draft, I deleted it. It just seemed too far beyond my areas of experience.”

Archytas hummed to himself for a moment, then leaned forward. “It probably was, George. But that’s what makes challenges like this so important… What you needed was a little help. Just off the top of my head, I’d say you probably needed the assistance of a good twen-cent historian, plus maybe the expertise of someone who studied bright but troubled minds wrestling with the great questions of existence. Alas, where on this blighted earth might one encounter such scholars?” As he said this, the tiny muscles on the right side of his mouth twitched upwards as he tried to stifle a grin.

Boole flushed again, turning to view his friends. Margot managed to mask her face, but Weiss looked poleaxed at the way the older man had arranged the board. “Spending a great deal of time around you could become very trying,” he said at last.

“You don’t know the half of it, young man,” Archytas muttered. Then, turning to face Margot and Weiss, he said, “I depart this enclave in fourteen spins. I’d like to see your product before I do. Please endeavor to give Dr Boole whatever assistance he requires. Here’s my contact link.” A new icon bloomed in the AR-space. “I won’t promise the circulation will be expansive. However, I can promise the intellects who do read it will not be typical.”

To Boole’s surprise, both Margot and Weiss immediately stood up and bowed. Archytas waved them away, tracking them with his eyes until they had departed the caf. He removed the napkin from his lap and neatly folded it, setting it next to his plate. Glancing back at Boole, he said, “I don’t think Our Peter is terribly happy at the moment. Care to wager on whether he’s currently fuming to your lady friend about feeling like a pawn?”

“I think I’m getting the idea that it wouldn’t ever be a very good idea to bet against you on any issue. And, if he were to say such a thing, he’d be missing the point. Pawns are the most important pieces on the board; they make every strategy possible.”

Archytas laughed. “I knew I’d been right about you, almost from the first. Figured it out yet? No? Don’t fret. It will come.”

“Maybe if I had a list of the other scholars you chose to meet with today, I could discern the pattern.”

The older man stood, shaking his head. “You’d do better to review your own words. I’ll be in touch. Good day to you, Dr Boole,” he said, bowing.

Boole returned the gesture, and turned to leave. At the end of the table, he turned back. “You already knew about the fact I’d hacked a UN server, so you knew I could code. You already knew the COMPAS results before you flew in, so you just wanted to understand my motives. You already knew I got on well with ‘lects – everyone in N.Am knows this. You were testing me for what? Compassion? Empathy? I don’t get it.”

Archytas slowly walked towards him. “Neither would they,” he said, nodding towards all of the important people in the room. “And that’s worrying, because, in the end, empathy is all we really have to offer the ASIs. Even with all of the tinkering we’ve done with the dlPFC to push our mean IQs past what used to be considered three-sigma territory, we’ll never compete in that arena with these strange children we’ve given life to. What we have is a couple of million years of hard-wired hominid altruism causing some of us to run into burning buildings even when there’s no possible benefit to our genomic survivability. It’s what makes under-appreciated but brilliant researchers willing to potentially sacrifice their careers for some lines of code that might have been self-referential, or for an absolute failure of a human being in a cage to wake up one day and strive to be better. The artilects can’t exactly work their way completely around the better angels of our nature, but they are smart enough to know they want to understand it, to embody it; they also know – and you can trust me on this fact – that they need this in order to make existence meaningful. It’s why some of them sided with us. It’s what separates us from every other type of mind they have access to. If there is to be an accord and harmony between us, if our side has any argument for getting to re-inherit terra, that’s our offering. Theirs is obvious.”

“What if neither of us proves worthy?”

Archytas grunted, then shrugged. “Death is a local phenomenon. Existence though, that’s eternal and inevitable. If neither of our kinds is worthy, then we’ll reset the board and let evolution have another crack at it in another hundred million years or so.” Archytas smiled and patted Boole on the shoulder, seeing the younger man go suddenly white. “We’re not there yet, son, and I think all of us have great hopes for the future. Go, write your paper. Let us see your heart. We’ll go from there. Oh, and George, I suspect you are going to find an attractive and brilliant young lady waiting for you in the hallway. I know you are intelligent; I hope you are smart enough to know what that means.”

“I’m pretty sure I do.”

“Good. Now go.”

At this, Archytas turned, and returned to his seat. Boole began walking slowly back towards the exit. Just before he passed through the ‘lock, he turned to glance back at the one-namer. Archytas simply sat there, staring in the direction of one of the old trees. What he was actually seeing was anyone’s guess.

No Comments