By Thomas Bartlett Whitaker

To read Chapter 22, click here

I paced, a shadow casting shadows.

The desert had found its way into the derelict warehouse, grain by grain, until the cracked concrete floors were coated in a half-inch of sand, little dunes radiating outward from the eastern wall. The desert is good at that. It’s patient. It knows it only needs the tiniest of cracks, and time.

It has that in common with evil.

Every few minutes I paused in my circuit to stare out of one of several dozen gaps in the crumbling cinderblock wall. From here, I could see across the broad green expanse of the communal area that stretched out from the rear of my taller all the way to the highway. How many times had I stood on my back patio and stared at these very holes and thought: if I were a sniper sent to put a bullet between my eyes, this is where I’d set up shop? Not this time, I thought, staring grimly at the heavy weight of the semi-automatic in my left hand. Its twin still lay hidden in my satchel, waiting, watching. I hadn’t known what to do with Chespy’s unwanted housewarming gifts the night before, when I erased my presence from the Monterrey condo. I’d thought about dumping them with the other details of my brief life in the underworld, but what if some kid came across them? In the moment, I didn’t question or analyze the sense of security that holding metallic death gave me. The world felt fragile, as if the clumsiest of movements would smash it into uncountable fragments, and I carried the pistol like a talisman. I wished that Blackie had stuck around, but after having spent a few minutes sniffing around the warehouse he grew bored with me and my silent vigil and departed for the company of other perros callejeros.

How long would it take for Chespy to realize that I had firmly rejected his offer? He’d shown me quite a lot. I might not be able to lead the police to the house on the mountain, but surely I could describe it. Maybe even some of the guests. Ditto for the thugs at the club. He couldn’t know how good my facial memory was, so he would have to assume it was perfect. Surely, they’d killed people for less. And what of el Lobo? I definitely knew how to find his office, and how to evade his security system. I didn’t think the Hammer would kill me for turning my back on him, but he wouldn’t have to. All he’d have to do is tell Chespy where I was.

Which he almost surely is doing right now, I realized with a grimace. I’d been so pleased to shove it all in Gelo’s face, that Chespy had gone behind his back to recruit me; I’d wanted to wound his pride to gain an advantage over him, and I’d succeeded. But in doing so, I’d forced him to try to find a way to win his pride back, and he was probably in town now, picking up a burner phone so he could chew Chespy’s ear off. They could be discussing the me problem right now. I gripped the pistol and tried to pretend it was some kind of an answer.

One corner of the warehouse was dominated by several ziggaruts of rotting packing crates. I hefted several of these over to my perch and stacked them into a chair of sorts. I settled back into this and waited. If someone came all of the way from Monterrey, they wouldn’t be able to arrive here for at least another two hours. I tracked the contours of my footprints in the sand, back and forth, always moving, never arriving. The day was heating up, the mercury weighing in at around 70°F, light for his class but hungry to advance. Why had I even come back here? I’d be better off practically anywhere in the entire Republica. The buses in Monterrey went everywhere; I could have spent the night in El Centro, popped over to Cuauhtemoc in the morning, and been anywhere within 48 hours. That would have been the smart thing to do.

“That would have been the smart thing to do,” I told myself, thinking that perhaps I could motivate myself into getting up and walking to the bus station. My body refused to be suitably motivated.

“You are going to get yourself shot if you stay here, pendejo,” I said, trying again. For the briefest of moments, the idea of putting the pistol in my lap to my head and pulling the trigger crawled onto the stage of my Cartesian theater, before I slammed the curtain down. The act itself was not what alarmed me: it was the undeniable feeling of pleasure that this thought produced. Suicide had for years seemed a reasonable option, but not something I’d ever been actually happy about before.

Time crept. An unending stream of permutations paraded across my vision, all of the ways they – whoever “they” were — might assault the shop, and what I would have to do in each scenario. How each of these responses was doomed to failure. A little past 3pm, a small group of children unrolled a garden hose and set up a small sprinkler head, one of the types that send twenty or thirty tiny jets of water up in the air in a slowly rotating wave. A girl of maybe five ran shrieking through the spray. Her one-piece bathing suit had Marvin the Martian on the front, his conical laser blaster pointed in the air. I looked down at the weapon in my lap and closed my eyes.

Children multiplied. The neighbourhood of La Curva was a grim place, a few dozen tumbledown homes and warehouses strangling a dilapidated thoroughfare. “Fun” was in short supply on most days, so the happy cries of the original three kids echoed out like the song of the sirens. Within minutes there was a crowd of at least ten, then fifteen. A group of boys showed up on bicycles, and tried to one-up each other by riding over heaps of concrete rubble. These mounds weren’t very tall, not more than 18 inches at their highest points, but the looks of determination on the faces of the boys were total. They were a year of two older than Kevin was when I taught him to ride his little electric-blue Schwinn. The color of that heavy steel frame lanced through my memory like a stiletto. I remembered how for months afterwards I would be gripped by the strangest combination of pride and terror when I saw him zipping down the sidewalks in our neighborhood. How I had nightmares for months of him ignoring a stop sign and getting hit by a car, and how I wasn’t out of elementary school before I knew what it was to regularly lie awake at night on my knees in prayer, clenched up in silent horror at all of the ways life could destroy you and the people you loved. I sat in the darkness and tried to track the path from those days to this one. I thought about the species of peace that I had acquired in the mountains, how it was predicated on the realization that after some types of mistakes, there could be no more dreams, that even fear and self-hatred were decadent for someone like me now, how a person could lose any right to anger and pride and love. I stared at the children for a time, new-old memories chipping away at the edges of my sanity, then stood up, packed the pistol away, and left the warehouse. Getting shot suddenly sounded vastly more preferable than having to listen to my internal monologue.

I returned to the taller by the front entrance, as far from the kids as possible. I didn’t see anyone watching my place, but I assumed that the sorts of people that committed murder for a living made a practice of not being seen. After unlocking the door, I left it open, and then looked around the space that constituted Emilio’s workshop. Some dust and sand had built up during my months of absence, but it didn’t look like much had changed. He’d gotten rid of the trunk-sized pneumatic machine that had once sat against the north wall, I noticed. The space where it had sat was clearly marked on the concrete, the only section of the floor that didn’t have a slightly oily sheen to it.

My apartment was undisturbed. There was enough grime on the floor to see a total absence of footprints. My admiration for Emilio soared. If I had six hungry kids and some apparently wealthy if eccentric foreigner had left his property in one of my buildings for months unattended, I’m not certain that I would have matched his integrity. Years later, a religious friend of mine would try to sell me on the idea that virtue was just vanity dressed up and waiting for applause. My mental retort, left unvoiced, was Emilio’s respect for my boundaries.

I spent the next hour or two evicting the spiders that had partially succeeded in retaking the office in my absence. I finally arrived at the point when I realized that I was wiping things down for the third or fourth time. I removed the pistols from my satchel, wrapped them in an old rag, and then hid them in the rafters, clips removed. I collapsed on the cot, and stared up at the tin roof. I’d caulked up all of the little holes that I once thought had looked like linear star fields, but one could still see little glowing spots if the internal lights were off. I concentrated on these until they went out of focus. Everything felt far away, even my life. I wondered if I had made the right decision telling off the Hammer. It felt right, logical. But everyone always feels that they are making the right decisions, even when they aren’t. And yet we seldom seem to remember this, and go on choosing in the same haphazard manner as before. Memory memory memory: I scanned through scenes of my past life, trying to arrive at some sort of estimation of the percentage of conclusions I’d ever come to that turned out to be false. At least half, I guessed, and that was probably an optimistic estimation. I pretended to be logical, but what if this was a label I kept insisting upon specifically because I was afloat on a sea of dissonance? Didn’t I feel my way to most of my answers? What would it be like to be truly rational? To view all of my internal mental processes as being suspect? To view every conclusion as a hypothesis to be tested, instead? Would that be madness or the path out of madness? Anyone would call your situation insane, I told myself. Look around you, look at what you have done. Whatever this is, it’s not even in the same zip code as sane.

It’s got to be an agency thing, I mused. A way to separate one’s actions from those of a chaotic world: I did this, so I’m sure of it. But there are truths about the universe that no human ever suspected, I knew. Until this past century, no human that ever lived would have agreed with the statement that we all live with a huge blind spot right in the middle of our vision. And yet it’s there, the result of a lack of photoreceptors where the optical nerve shunts from the eye to the brain. It gets filtered out, meaning that all we see is a simulation. I shifted in the cot. What if I was as skeptical of all of my thoughts as I was about those that came from other people? What would life be like if I was able to remember this blind spot and what it signifies every single time someone spoke, every single time I spoke? I pulled a towel over my eyes, wishing desperately for sleep, if only to shut myself up. Descending into the oneiric world had long ago become the best part of my day, I realized, and wondered if death really was such a bad option.

Annihilation never came, despite my hopes and dreams. The sun finally fell, and I realized that I had been thirsty for some time. I had emptied out my tiny refrigerator before moving to the mountains, so I slipped my shoes on and walked a few blocks to the closest deposito. The day had been warm but the April nights refused to let go of the memory of winter. The wind assailed me but I hardly felt it.

The storekeeper nodded to me from the upper edge of an unfolded newspaper when I entered his deposito, but said nothing. I noted the label at the top of the front page. I gathered a few things together and paid for them with some of el Lobo’s squeaky-clean cash. I turned to go but then thought about poor men in backwater towns who still managed to summon the will to read the most intellectual of a city’s newspapers and what that might indicate about that person’s life narrative. I turned to look at him again. He was still staring at me curiously as I stepped back up to the counter.

“Pardon my abilities with your language. If I say something that is unclear, please let me know. Does life seem like a prison to you?” I asked uncertainly. “Does this statement seem … illogical, or perhaps even insane to you?”

If the proprietor felt any surprise at my question, he didn’t show it. Instead, he settled back onto his stool and lifted his eyeglasses up so that they perched on the ridges of his eyebrows. For the first time I noticed the anemone patchwork of red veins on his neck.

“A veces, I suppose. Yes. The obligations of family, work. The difficulties of surviving in this place. Growing older. I suppose it can seem like a sentence at times.”

“No,” I cut him short, wanting to forestall a discussion of the specific hardships that each individual life might contain. “I’m talking about something bigger than that. Como… destiny, maybe. How much free will do we really have? Maybe that’s not what I mean,” I said, rubbing my brow. “It’s like….sequestration is the existential question par excellence. Me entiendes?” He waved me on.

“Man…me…I have for many years now felt as if I was derelict, cut off from an indifferent world. I have never had a place where I felt I belonged, and this made the cosmos feel meaningless. I feel as if I am sometimes outside of it, ontologically speaking.” I tripped a little over these last words in Spanish, but the man kindly corrected me. His smile made me feel convinced for a moment that I truly had lost my mind, so I closed my eyes for a moment and gathered my thoughts. “What I mean is: life doesn’t take place in prison, it is a prison. The prison has an insurmountable wall: death. And when you come to see and understand death not as an abstract but as something immediate or tangible, what is left? What is one to do?”

“You are not religious?” he asked at once. “A believer would say that death is recuperable.”

“I don’t know anymore. I was. But I tested the omnibenevolence of my God and he didn’t show up. Do you believe in these things?”

He was silent for a time. “For me, I do not know. It seemed that I did when I was younger. For my wife and my children, and soon, my nietos, I will say that I believe. But between us men I do not know. Sometimes…I see no path for me. I cannot live in the world of the scientists, the atheists. They say that there is no eternity, no divinity. And yet I feel eternity in everything, God in everything. But I think too that the people that make God into a person are wrong, and very stupid most of the time. Maybe the old ones had it right, that God is the world, and we defeat death for a time when we are able to think about the eternity in everything without making ourselves a part of it.” He smiled at the look on my face, and I shut my mouth. “You are American, yes? Do you know your Wallace Stevens?” I shook my head. “You should find a book that contains his ‘Sunday Morning’. It is close to what I mean.”

The world tumbled around me. This was not the conversation I had expected. He sensed my discomfort and leaned forward, “If life is as you say, a prison, then, again for me, I can only say that family is the key to these walls of death you speak about.”

I turned to leave. “Hombre!” he called to me as I reached the door.

“I am not a man,” I said to the night.

I didn’t want to return home, so I walked. I stopped for a few minutes in the Plaza Grande, watching the police come and go from the stationhouse in their trucks that Gelo had paid for. The temperature of the air kept falling, so I got up and moved on. I passed by Don Hector’s muebleria; the lights upstairs were still on and I thought about stopping but quickly decided against it. I felt like I needed to talk to someone but I had no idea the words that needed to be said. Autopilot engaged, I found myself tracing a path between all of the various worksites that I had toiled over while in Hector’s employ. After an hour I stopped at the house with the pool, looking at the still unfinished partition that was growing up in place of the wooden fence posts I had ripped out months before. Hector was forever bouncing from task to task, so it didn’t surprise me that the thing was unfinished. I could easily imagine him arriving in his red truck, telling his crew that they needed to pack up their gear, that they were required elsewhere. I sat down on the fledgling wall and stared up at the sky.

This part of town was dominated by large houses hidden behind even larger walls. I knew that the castle directly across from where I was sitting belonged to the smuggler Julian, possessor of a supposedly vast store of wisdom that he was never going to give me access to. He never managed to say anything without his words implying some sort of sneer being attached to them sub-rosa, and the thought of bumping into him while still submerged in this vast sea of exhaustion revolted me at first. I could only imagine the scorn he would heap on me, and I nearly walked away. What gave me pause was the look in Stacie’s eyes when she sent me to find Julian last year. I’d never figured out the riddle there. No doubt he knew plenty, but it seemed pretty clear from our brief moments of contact that he didn’t think much of me, and there wasn’t anything about my present state that was likely to improve his impression. Still….he knew this life, he’d survived it and profited from it. There was something there, maybe wisdom. And I badly needed wisdom, I knew. The wall surrounding his compound was at least eleven feet tall, but I could see that some of the trees in his backyard were underlit still. Fuck it, I thought, as I stood up and marched across the street. I knocked heavily on the steel door before I could think my way out of it.

It took several minutes, but eventually I heard a series of locks click. The door inched open and I was greeted with Julian’s icy stare.

“I can no longer act in my best interests,” I said before he could hit me with something sardonic. “I know what would be best for me, but I can’t do it. It’s not a zugzwang thing. It’s that…well, I don’t know what it is. Do you?”

He stared at me for a long moment before nodding. I took this as an invitation to enter and stepped forward, which was when he slammed the door on me. I reached to feel how close the surface of the door was from my nose, and couldn’t squeeze a finger into the space. I sighed and left.

Half an hour later I was back, bearing a bottle of the most expensive bourbon I could find in town. I knocked heavily again. He was quicker to respond this time.

“Look, boy gringo…”

“I think I’ve been testing the universe for a moral center for years, and now that I’ve finally convinced myself that there isn’t one, I don’t know what to do. Look: I brought you booze.”

He looked me over again, before reaching out for the bottle. “Fine. Are they coming in with you?” he asked, nodding behind me.

“Wha?” I asked stupidly, turning around to look behind me. I heard the door slam behind me and winced.

“Hijo de…” I murmured, taking stock of the situation. The man’s concrete partition was easily beyond my ability to scale simply by jumping. Like most of the streets in Cerralvo, Julian’s avenue was lined with cars. I stepped back and traced the perimeter of the property until I found what I was looking for. So far gone was I that I didn’t even stop to wonder if the Dodge Ram I climbed on top of had an alarm. I can only imagine what the owner must have thought the next morning when he saw my dusty footprints march up his hood and onto the roof of the cab. I tested the limb of the oak tree that extended above and over Julian’s wall. It seemed sturdy enough, so I hefted myself up and climbed into his backyard. I spent a moment scanning the lawn for dogs, but didn’t see any. I dropped down onto the grass, pausing to admire his digs. Running contraband had paid off for him. The architecture of his place looked like it had been copied from a small palace in the south of Spain, with abundant Moorish arches and plenty of tile mosaics around the pool. Everything was white, and the house shimmered slightly in the glow of the submerged pool lights. The entire visible portion of the house was wrapped in a huge outdoor patio, and I followed this around until I came to a series of windows that looked in on Julian’s kitchen. I could see the man through these, opening my bottle of bourbon as he sat down at a table. I located the nearest door and let myself in.

“The last few days I’ve been starting to realize that my whole ding-an-sich might be completely fucked,” I stated, causing him to choke on the first sip of whiskey that he was just in the process of swallowing. “You know what I mean by that? Of course you do, knowing things is what you do! How could my perceptions and thoughts be accurate if the underlying foundation is cracked?” I ignored his sputterings and moved to the sink, where I started searching the cabinets for glasses. I found them on the second guess. I moved back to the table and sat across from Julian, close enough to see him but far enough that he couldn’t hit me. I poured myself a few fingers from the bottle. I was just noticing the midnight black cat stretched across the windowsill when Julian found his tongue. I almost made the obvious joke but refrained.

“You must want to get shot,” he gasped at last.

“I’ve been shot. It didn’t take.”

“You didn’t get shot by me, since you are still sitting here.”

“Try to keep up, Julian. I’m pretty sure we both know I’ve been trying to tell you for the last hour or so that I don’t think I would much mind dying.”

He stared balefully at me for a few minutes before taking another sip of liquor. “So. You say you cannot act in your best interests. This is an obvious point, since you broke into my house and are sitting in my kitchen. What does this mean?” he asked at last, proving that he’d at least been listening as he contemplated the timing of slamming his door in my face.

I explained to him where I’d been for the last few months, the things I’d seen and done, the things I’d avoided. He grunted at certain points in the story, though not at the ones I’d expected. He didn’t say a word about the mountain mansion.

“So. You are convinced that you will die if you stay here. And yet you will not go. This is the heart of the matter, boyo?”

I nodded. He sat silent for a long while. The black cat opened an eye to stare at me, and then yawned. It stretched itself out luxuriously, licked the fur on its side, and then came to sniff at my legs. I picked it up and ran my hand over its head and down its back. It didn’t purr, but settled down and closed its eyes. It appeared to be asleep within minutes.

“You said something about a moral center. You mean what? God? John Rawls? American values? What?”

“God, yes. I was a super-believer once. I mean, I was as far into that world as it’s possible to go. Joined youth movements that would have fit any of the technical definitions of a cult. Denied scientific truths that I knew were true by the force of my will. Thought that the normal temptations of a boy going through puberty were literal demons sitting on my shoulder, shoving some kind of spectral tentacle through my skull and into the place where body and soul were supposed to meet. Absolutely knew that this point was the pineal gland, because Descartes said so, and nevermind what the neurologists said. I had few friends growing up because I thought they all led me into sin. That deep.”

“So? You think you are the only person like this? The man next door is a PAN hack and fixer. Everything he does is for the party. The party can do anything, and will. This is human nature, to believe in tonterias.”

“I didn’t think it was stupid. I just…it’s the contradictions, you know? I’ve always noticed them. It bugged the hell out of everyone, but I didn’t know how else to search out the Numinous. My Sunday school teachers hated me, I think. They used to transfer me from classroom to classroom. Eventually I just couldn’t ignore everything. I had to know whether any of it was true. Not comfortable, or pleasing, or self-justifying, or consoling, but true. I started…testing things, I guess. People. Their level of hypocrisy.”

Julian grunted. “People fail their ideologies. This says nothing about the ideology, only the human.”

“I think you are wrong. I think the accumulated actions of adherents are some of the only ways to test the social usefulness of an ideology. But I understand what you are saying. So I… look, I know this sounds crazy. It is crazy. I don’t really understand now how this seemed sane to me. But I…I thought up the worst thing I could. I kept asking myself: what is worse than this? What is so bad that a God with any pretentions of goodness would have to stop it? I don’t know why I didn’t think of the Holocaust, or anything like that. I was too wrapped up in my own personal universe of pain. I just knew that if I kept moving the benchmark for the worst act I could imagine, I’d finally arrive at something that would require God to show himself to me. At first it was just a … a thought. But then it became something else. I don’t know how. It all seemed so necessary, so non-contingent. I knew – knew — that if I actually tried to do this thing, that God would have to stop me. And then I’d have my proof. It was just too terrible. It shouldn’t be allowed to happen. I didn’t think it would. There were a million ways it could and should have failed. I made it easy for God to stop it. But then he didn’t. And I don’t know what this means.”

“Absence of evidence is sometimes evidence of absence.”

“Maybe. Or maybe I warped myself into such a bent shape that I can no longer trust the conclusions my mind produces. The last few days I’ve been feeling like my brain is some kind of parasite that is attempting to destroy me.”

Julian blinked his yellow eyes at me and sipped at his drink. “Or maybe God is just colder than you believed. Remember Job’s children? The original ones, not the second round.”

“Of course. They got butchered.”

“Yes, by God. Not by Satan. God. Lucifer was merely an effect of God’s attention. He gives Job new children, and this is supposed to be a happy ending, but I’m not sure the originals would see this as much of a compensation. People never seem to want to consider that when it is said we were made in the image of God, this includes all of the evil, the madness, the horror, too, even though this could explain a great deal, no?”

I lifted the cat up gently and deposited it on the table. Julian didn’t try to stop me as I found the front door. I was a little drunk by this point but I made it back to the taller and managed to pass out.

That day I lay in my cot and watched tiny rays of light move slowly across the floor, illuminating brief flashes of dust in the air. I didn’t eat, don’t recall getting up to drink anything, though I must have at some point. When night fell I put on a shirt and walked back to Julian’s. I couldn’t read the tiniest hint of data in his eyes when he opened the door and stared at me for a long moment. Finally, he grunted and stepped back, leaving me to close the door behind me. I followed him into his den, where he sat in a leather armchair and resumed staring at me as if he were trying to decide whether or not I was worth dissecting. I sat on a couch and stared at the floor.

“What about justice?” I asked finally.

“What about it?”

“I think that’s why I’m not able to run. It isn’t…right what I’m doing, what I’ve done. Running from something I should be facing.”

“If that were true, you would go back to where you came from.”

I nodded and wiped my hand across my face. “I don’t think I’m strong enough for that, either.”

“So, you are trapped between cowardice and audacity. Welcome to the human race. Most everyone alive is mediocre in this way.”

I sat there again for several minutes, mulling that over. “That’s not very helpful. Do you believe I should just…live like this? Hiding away in this backwater place?”

“Of course not. I think you are being very stupid. I have no idea what you are about down here, not really, but you are with the wrong people. Amateurs. Psychopaths. People who don’t realize that it’s no longer 1975 and all the rules have changed. And you are being too visible for whatever it is. You should run. Now,” he punctuated this last with an angry tapping on the arm of his chair with his forefinger. “But why ask me? We are nothing. Have I ever sought you out? Have I given you any reason to think that I want to speak with you?”

“You opened the door.”

“Only because if I did not, you would have broken in the back door.”

I remained silent, not having an answer for this. The silence drifted in between us, like a creeping fog. Julian’s cat pranced into the room at one point, gave the two of us a quick scan, and then hopped up on the couch and into my lap. It put its paws up on my chest and leaned forward to smell my face. I smiled at the oddity of Julian, one of the least friendly people I’d ever met in my life, having the nicest cat in creation. It quickly curled up in my lap again and proceeded to fall asleep. Apparently I was a better pillow than Julian.

“Justice. You speak of the thing as if you know what it is. I find this to be a common fault of Americans.”

I again didn’t know what to say to that, so I just sat there, petting his cat.

“That was a question, boyo.”

“Oh. Justice is… just deserts, I guess,” I said finally.

“And yet everyone has a different idea of what that means. All you’ve done is change the terms. You still haven’t told me what it is.”

“Okay. It’s a category of closure.”

“Another American word for a thing that doesn’t exist. Let me tell you something: for the people that desire closure, the ones that believe in it, they don’t really want it. What they really want is erasure. And that’s a very different thing.”

“Okay, I guess I can see that,” I murmured, pausing. “Since erasure is a fantasy, then I guess what people want is vengeance. Revenge. ‘You did this to me, so now I do this to you.’”

“If that were true, we’d be no better than the Bronze age goat herders who saw a god under every rock and wailed incessantly about ‘an eye for an eye.’”

“Are we? No, seriously, I know we have better tools, better toys. But are we really so different?”

“You don’t get to appropriate the cynical high ground with me, guedo. If you believed what you just said, you’d be running from here with a clear conscience.”

“My memory is too good to have a clear conscience.”

He breathed deep. “Let me tell you what justice is. Justice is survival. That’s it. This world kills us all in the end, but finding ways to fuck it at every opportunity is justice. The rest of it is just power, people protecting their interests, promoting their religions or ideologies, trying to ignore the greater truths. I don’t care about your past. Understand that. I’ve worked with people that have done evil to a degree that you couldn’t even imagine. This whole town is full of them. It’s practically a graveyard, with all of the closets filled with skeletons we have around here. But neither do I have the time to care about fixing your conscience. You understand? I want you to leave. Do not come back. Do not knock on this door. It will not open for you.”

A world of closed doors stretched out around me. I attempted to return to my old life working for Don Hector, like a corrupted hard drive trying to reboot at its last recorded stable configuration. I tried, but it wasn’t the same. Don Hector’s vanity and his incessant greed no longer bothered me; I hardly noticed them anymore. I couldn’t completely ignore the way he kept trying to work out his dislike for the Hammer by punishing his “son”, but even this seldom produced any genuine emotions in me beyond a low-grade form of scorn. It seemed to bother Raul far more than it did me. That May, the crew was tasked with expanding the showroom of the smaller of Hector’s two furniture stores. This involved building a rooftop patio area and playground for Junior’s kids, which entailed moving thousands of pounds of concrete from the ground up two floors. Hector was too cheap to buy or rent a mixer, so several of the Maestro’s men remained on the ground, mixing the concrete up with shovels, right on the surface of the parking lot. Hector tasked me with manning the rope and pulley system on the roof, meaning I lifted every bucket of concrete used in the entire project.

“Let me help,” Raul insisted, on one of his rare showings at the site.

“I’ve got it,” I grunted, locking the rope into an anchor and then swinging seventy pounds of liquid mezcla over the lip of the roof.

“It’s not right, this. Usually people take turns.”

“Oh, it’s right,” I answered, hefting the bucket out of the way.

Perhaps because he was ashamed of his father’s behaviour, Raul invited me to Monterrey my second weekend back for the Classico, the huge game between the city’s two professional futbol teams, Los Tigres and Los Rayados. I wasn’t terribly keen on the whole thing, but my autopilot was engaged and I agreed to attend mostly just to get him off my back. In my absence, Raul had gotten engaged to his long-time girlfriend, Elizabeta, and he seemed very pleased with himself. Both of them were fanatical supporters of Los Rayados, and his Monterrey pad was ground zero for a huge group of his former school chums. The Friday night before the game, he invited nearly a hundred people over, most of whom seemed to think there was some sort of a race on to see which keg they could float first. I tried to blend in, but a conversation between hipsters over the pros and cons of Guadalajara synth rock, metal-tinged darkwave, and cosmic krautrock had the little muscle under my right eye jumping. I quietly snuck out the back and rode the elevated train for a few hours, eventually ending up standing across the street from el Lobo’s building. I stared up at his darkened window for a few minutes, then walked towards the Macroplaza. By the time I returned to the house in San Nicolas, most everyone had left. The few stragglers still awake were so drunk that they didn’t notice me when I let myself in. Three bodies lay comatose in my bed. For the briefest of moments, I imagined myself dragging them out into the den, but then I recoiled. Those were Chespy’s thoughts. I caught a cab back to el Centro and rented a tiny room for the night at one of the cheap hotels adjacent to the bus depot.

I woke early the next morning and watched Sky News for an hour, waiting for the noise to pick up on the street outside. I checked out at 8 o’clock and found a small café serving what were actually pretty decent croissants. I was on my second cup of coffee when I noticed the woman. She was walking fast, her right hand rubbing lightly on the skin of her throat. As she passed the patio of the café, she looked behind her, the concern obvious on her face. I left some coins on the table, folded up my newspaper, and carefully wiped the lip and handle of my cup down before heading in the direction she was fleeing from.

Three blocks down I saw the first police cruisers. As I neared, I also noticed several vans emblazoned with government acronyms. A small crowd of several dozen bystanders were lined up across the street. I mixed in with them, listening to their conversations. A number of bored officers stood sentry in front of an alleyway that ran between two smallish office blocks. Uniformed men came and went. I was about to leave when an open-bed truck backed up to the alley and several forensic technicians folded down a metal ramp and unlocked a dolly. A woman on my right was absentmindedly running her fingers across her rosary. When the technicians began rolling immense metal drums out and loading them into the truck, I heard several gasps. A man with immense forearms wept silently, and then left, crossing himself as he did. I seemed to be the only person in attendance that didn’t seem to understand what I was looking at. I glanced around and noticed a man in a cheap suit, smoking furiously, a few yards outside of the crowd. His eyes flicked over as I approached.

“Disculpame, pero que ha pasado aqui?”

“You know of the pozole, guedo?” he said in Spanish.

I thought for a moment. “You mean a kind of meat stew?”

“Si, eso es. Only that pozole over there was made with people.”

I blinked and turned back to watch the men, still loading. Eight barrels, I counted, still wrapping my head around the thing. I looked up, suddenly very tired. The day was heating up, the sky a beautiful blue. A flock of sparrows flew around the edges of the alley, nesting in the eaves of the buildings.

“Como lo hacen esa… monstrosidad?” I asked, turning back to the man, who was lighting another cigarette. He offered me one, and I accepted.

“Con acido de algun typo. De donde eres? Los Estados Unidos?”

“No, Canada.”

“No pozole in Canada.”

I shook my head. “Not yet. It’s … some kind of message?”

“Si. There will be names painted onto the barrels, the names of the dead narcos. Usually some sort of taunt to the leaders of these men.”

“Who would do such a thing?” I asked, thinking that even this was beyond Chespy, and then wondering if this was true.

“That’s the message: what man could do this? Not a man, obviously. Something else. Something you should just close your eyes and accept. You see?”

“Hard thing to miss, primo.”

“Go back to Canada, guedo. Find a nice Canadian girl, make nice Canadian babies. Hell has come to these mountains.”

When I returned to Raul’s house I found at least a dozen people still asleep. I didn’t envy any of them the hangovers they were due for when they did return to the lands of the living. I found the coffeemaker and brewed a pot. The living room reeked of stale beer, marijuana, and sweat, but I hardly noticed. A fat kid was sprawled out on the sofa, but the love seat was empty. I used the remote to turn on and then mute the television. I sat there, drinking coffee, watching the world crumble to pieces. I took the thin leather cord that hung around my neck off, running my finger around the edge of the silver ring affixed to it. I thought about Her, about December the 10th, about everything.

Uncountable eons passed before Raul stumbled out of his bedroom, bleary-eyed. “That’s café?” he asked, nodding to the cup sitting on the small table to my left. I nodded back and he drank what was left in the cup in one gulp. He made a face, then plopped down on the couch, sitting directly on top of the sleeping man’s legs. “Bitter. There’s sugar in the cabinet.”

“I’m sweet enough.”

“Yes, that’s what everyone always says about you. The nicest robot in the world. It’s a good thing I’m a Catholic in good standing, because suicide looks very attractive right now.”

I looked at him, wondering if he was trying to be funny or maybe something deeper. He solved the riddle by belching and then scratching his leg.

“You smell like old cheese wrapped in gangrene,” I told him at last.

“Si. Just wait. I’ll be ready for the game in a few hours. You thought last night was a party. Tonight’s going to be epic.”

People came and went all afternoon. I helped clean the place up, and went with two of Raul’s friends to return the kegs. Two hours before the game, people started to arrive, completely bedecked from head to toe in club regalia, everything from jerseys to scarves to hats and, in one case, a Rayados purse. Raul and two of his girlfriends started painting faces in elaborate designs. One of these pranced towards me, obviously several drinks in already. I caught her hand when she tried to start painting my nose blue.

“I’ll pass, thanks.”

She made a faux-pouty face and then kissed me. Everyone cheered and then she was gone, moving on to the next living canvas. I felt frozen inside. I had a sudden vision of the damage I had done to myself over the years, the distance I had sailed from the shores of my fellow man. I shook my head to try to clear it. When this didn’t work, I took an offered shot of tequila. That didn’t work either, but it made me look like I was trying to be a good robot and join the party, so downed another.

The neighborhood surrounding the stadium was riven in two. Every street was lined with barricades and partitions, all constructed in an effort to funnel Tigres supporters to one ingress point, Rayados fans to another. Even the public transportation system had divided the trains and buses up into two camps, yellow and blue, separated for miles and miles, everyone content unless they somehow blended into green. This seemed bizarre to me, and Tristan, one of Raul’s friends now studying architecture at Tec, explained to me that there were major socioeconomic differences between the two sides. Tigres supporters were typically poor and, to him at least, less educated, while those that followed the Rayados tended to be wealthier and white collar. Fights between the two sides were not only common, but expected. I smiled when he referred to the uber-Tigres supporters as “los hooligans,” pleased in an odd way to find this word had infiltrated the Spanish-speaking world.

The stadium inside was also divided into two halves. Separating the two were a pair of chain-link fences, separated by perhaps thirty empty seats that ran from the field all the way to the top of the venue. This seemed a little like overkill to me, but the vibe was not something I’d ever experienced before in America so I didn’t say anything. It was like a massive ritual, I decided after a few minutes. Massive drums boomed all around us as we found our seats, only thirty or forty feet from one of these partitions. Raul explained that the “ultras” – the most committed fans – sat next to the fences, so they could mock the other side’s ultras. I was literally the only person within a hundred feet not wearing something with a Rayados crest. Traffic flares were lit, the stadium seethed with competing chants, the baseline of the drums driving, driving, driving. Banners wept from the upper sections. Rayados flasks were passed around, and I understood in a visceral sense what people meant when they described crowds of people as a powderkeg. The game itself seemed like an afterthought.

The flame caught halfway through the second half. I don’t know how it started, but suddenly the tenor of the screaming around me changed. I turned to the right and saw what looked like shooting stars fly across the crowd in front of me. I instantly ducked, and then everyone was surging, stumbling away from the partition. It was later reported that several dozen Tigres fans had snuck hundreds of bottled beers into the stadium, drank them, and then started fastballing them over their fence directly into the chain-link on our side. Once the bottles hit the fence, they exploded, sending shattered fragments everywhere. A woman tripped and fell on her knees right in front of me. I leaned down to help her up and a mosquito stung my forehead, roughly two inches above my left eye. I ignored this and followed the crowd.

By the time I reached the parking lot EMTs were deploying, and police were roaming about, though it was hard to tell exactly what they were doing besides trying to look important. The play was halted on the field as order was restored. I walked out of the stadium, looking at all of the people who were receiving medical attention. A man sat dazed on the concrete as a female doctor looked at his eye with a scope. She saw me standing there and motioned me forward.

“I’m fine,” I said, stepping back.

“You are not fine. Come,” she said, pointing at my head. I reached up to find a small river of blood had somehow found its way down my face and neck, without me having noticed it. I looked down to find that this was starting to stain my undershirt. The doctor took a look at the wound and then used some tweezers to pull a tiny piece of glass out of my skin. She wrapped this in gauze and placed it inside a biohazard bag. I felt my pocket vibrate as she was bandaging the wound. The woman was a total pro, and she patted me on the cheek and moved on as soon as she was finished. I took out my phone and found a text from Raul, letting me know that they were gathering in a different section to watch the finish. The place was swarming with police, and I really didn’t want to hang around. I sent a text back about having met the female robot of my dreams, and not to wait up. He didn’t respond.

I wandered away from the stadium, and eventually found a subway station. I got off the train once we reached the downtown area and found what looked to be a relatively clean taco stand. Several of the televisions were set to the game, which had ended half an hour before. I ordered a plate and a Topo Chico. This part of the city stayed up late, and the stand was very busy. There wasn’t a single woman in the crowd, I noticed. Most of the men were older, and seemed to be bonding over the obvious descent in general character of Mexican youth as they watched scenes of EMTs stitching up bloodied fans. Several men on my left argued half-heartedly over which side was to blame. One of the cooks plopped a plate down in front of one of the men and then nodded at me. “Preguntale a ese caballero.”

Several heads turned to take in my bandage and the blood on my shirt. I could see them analysing the quality of my clothes and arriving at the conclusion that I was a Rayados supporter. “Bueno, who started it, guedo?” one asked.

I shrugged, pushing my empty plate forward. “I couldn’t tell. Bottles started flying and I left.” I stood, and pulled several coins out of my pocket. The man on my left nodded sympathetically.

“Maybe they’ll get the scoundrels, no? There must have been many cameras all over the place.”

Someone else snorted derisively. “When was the last time the police caught anybody? No, they’ll get away with it, just like they get away with everything.”

I shook my head, feeling the weight of the ring pressing down on my chest. “Nobody ever gets away with anything. You get away without.” I turned and walked away, a shadow moving into deeper darkness.

To be continued…

|

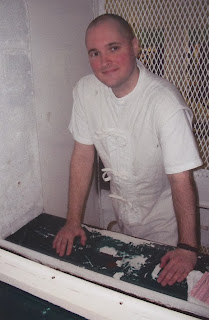

| Thomas Whitaker 02179411 Coffield Unit 2661 FM 2054 Tennessee Colony, TX 75884 |

Donate to Thomas’s education fund here

11 Comments

No Mercy For Dogs Chapter 24 - Minutes Before Six

April 1, 2021 at 10:21 am[…] To read Chapter 23 click here […]

Alex G

February 10, 2019 at 8:05 pmLindsey,

The paragraph you quoted is written in the form of a theodicy, i.e. a vindication of God's justice in the face of evil as a condition of the temporal world. For Thomas, proof of God's existence here is linked to the ultimate transgression: if God exists, he will manifest His will to prevent evil. There is also an ontological claim here: God's nature is infinite goodness and the world–though fallen–is the ethical purview of God, so God must reveal Himself to man in order to prevent great evil. If Thomas is here referring to his moral transgression, then his quest for God is the story of the sacrifice of Isaac in reverse. At the moment of sacrifice, God reveals Himself and commands Abraham to stay his arm. By virtue of His goodness, God will act manifestly to prevent great evil.

As for Thomas's claim that the event on that night was not supposed to happen, he means simply that there never was any plan that unfolded over time. There was simply a chronology of events that occurred in diachronic time, but these events were not causally connected to any final event. Each event was simply a perverse game, not a plan that was supposed to be a culmination of all preceding events. That is the poignant ABSURDITY of what happened to Thomas. There was no plan, no motive. There was merely a collection of contingent events that were then assembled by the court into a narrative of meaning–very much like Camus' absurd protagonists.

Alex G.

Bridgeofsighs

November 6, 2018 at 11:30 pmAnother good chapter. Thanks Thomas.

Expecting God to intervene to prevent a murders you planned is the ultimate bad bet. Wonder if this comment will be published..

Alex G

November 6, 2018 at 2:39 pmLindsey,

The paragraph you quoted is written in the form of a theodicy, i.e. a vindication of God's justice in the face of evil as a condition of the temporal world. For Thomas, proof of God's existence here is linked to the ultimate transgression: if God exists, he will manifest His will to prevent evil. There is also an ontological claim here: God's nature is infinite goodness and the world–though fallen–is the ethical purview of God, so God must reveal Himself to man in order to prevent great evil. If Thomas is here referring to his moral transgression, then his quest for God is the story of the sacrifice of Isaac in reverse. At the moment of sacrifice, God reveals Himself and commands Abraham to stay his arm. By virtue of His goodness, God will act manifestly to prevent great evil.

As for Thomas's claim that the event on that night was not supposed to happen, he means simply that there never was any plan that unfolded over time. There was simply a chronology of events that occurred in diachronic time, but these events were not causally connected to any final event. Each event was simply a perverse game, not a plan that was supposed to be a culmination of all preceding events. That is the poignant ABSURDITY of what happened to Thomas. There was no plan, no motive. There was merely a collection of contingent events that were then assembled by the court into a narrative of meaning–very much like Camus' absurd protagonists.

Alex G

November 6, 2018 at 5:03 amThis comment has been removed by a blog administrator.

Steph

November 5, 2018 at 2:51 amI am curious if Thomas story will be told on tv…what he's dealt with in the last yr etc…

Joe

November 1, 2018 at 8:29 pmAlways great to get another installment of NMFD. Thank you Thomas!

Pearls

October 31, 2018 at 12:58 pmI agree with you Lindsey,I think this "thing" he's holding back we'll probably never know.Every time I read Thomas work I keep hoping he might say it but as usual he never said it.Nevertheless we appreciates you and your work Thomas your presence is felled.

Lindsey

October 28, 2018 at 9:57 pm"So I… look, I know this sounds crazy. It is crazy. I don’t really understand now how this seemed sane to me. But I…I thought up the worst thing I could. I kept asking myself: what is worse than this? What is so bad that a God with any pretentions of goodness would have to stop it? I don’t know why I didn’t think of the Holocaust, or anything like that. I was too wrapped up in my own personal universe of pain. I just knew that if I kept moving the benchmark for the worst act I could imagine, I’d finally arrive at something that would require God to show himself to me. At first it was just a … a thought. But then it became something else. I don’t know how. It all seemed so necessary, so non-contingent. I knew – knew — that if I actually tried to do this thing, that God would have to stop me. And then I’d have my proof. It was just too terrible. It shouldn’t be allowed to happen. I didn’t think it would. There were a million ways it could and should have failed. I made it easy for God to stop it. But then he didn’t. And I don’t know what this means.”

Are you trying to say you hatched a plan for somebody to come in and kill your family because you wanted/expected God to intervene in it, somehow, so you could have proof he was real? Did I read that right? And is that what you mean when you speak of that night/event and say it wasn't supposed to happen?

Lindsey

October 28, 2018 at 9:55 pmI'm glad they didn't kill you, Thomas. I've been at home recovering from surgery the past week and reading your blog has really helped pass the time! I see they didn't publish my earlier comment asking if you were implying that your crime was because you wanted proof God was real, but just so you know, I didn't mean it offensively, I was just going by what I read in this entry. I get how that may be be too personal of a question, though. Anyway, I do get the impression you're holding something back whenever you talk about your crime. What that "something" is, we may never know. But either way, thanks for keeping me occupied this week with good reading material, that, alone, makes your life have value to me and probably others who read this blog, too. Cheers!

Pearls

October 21, 2018 at 10:44 pmI have been waiting for a while for this. Hope your doing well Thomas. You had quite an adventure back there didn't you.