Go against your principles and morals enough, and part of you will drift away until you lose yourself and are no longer. Your soul will eventually diminish, the essence of you disappearing in smoke. If man chose his time to go, I wonder if he would prefer death in the physical or spiritual form? The differences between the two are often magnified, and the similarities overlooked. Maybe the more pressing question is: if you caught yourself teetering on the edge, knocking on the door of either form of death, would you take drastic measures to stop it or would you just let it go?

Imagine life at its full peak.

Then imagine lying dead in the arms of your enemy..

Imagine peace on this earth when there’s no grief.

Imagine grief on this earth when there’s no peace.

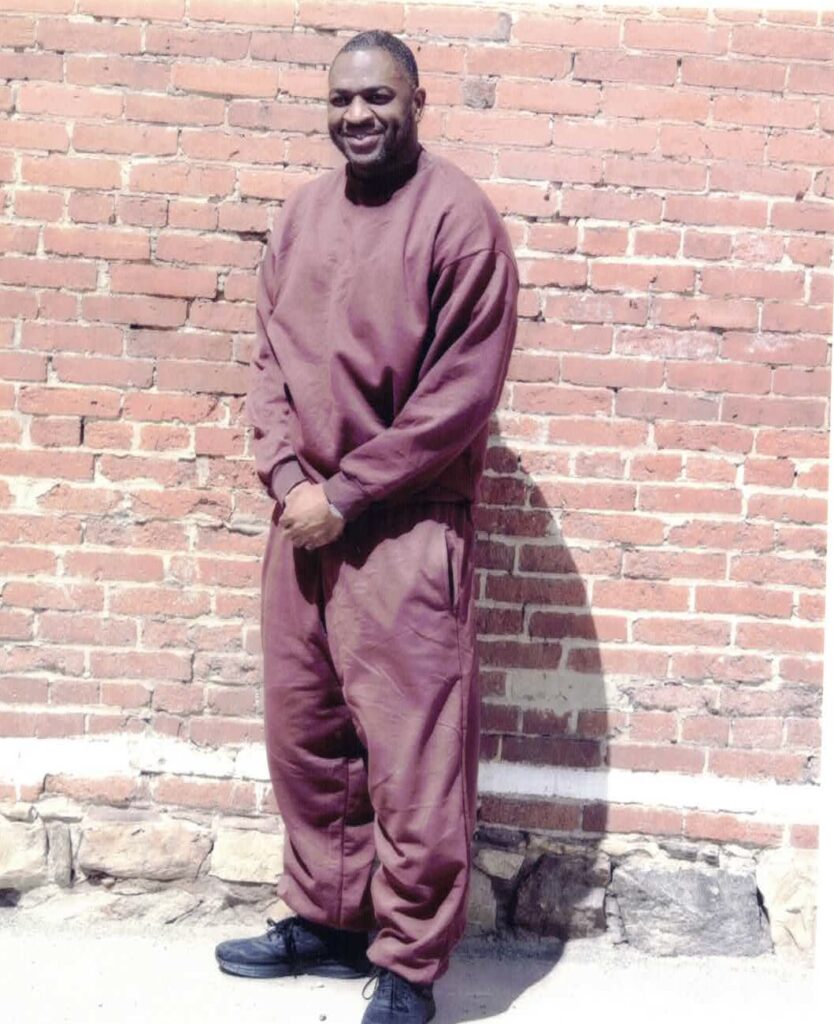

My first day on the job was uncomfortable. I felt like a question mark at the beginning of a sentence, out of place and hard to read. As discreet as the staff tried to be, the racial overtones were evident in our interactions. Thanks to them, I learned that when caucasians joke about something, it’s usually a way of expressing their true feelings or intentions. A route used to soften the blow, sort of speak. I was introduced as Remy to some and as Mr. Mulligan to others. Their mouths said hi, how are you but their facial expressions spoke louder. Exclamation point, question mark, period, period, comma. What the! How did you get this job? and Hmmm. One staff member was a black prisoner from Detroit working in the infirmary of a prison situated on the outskirts of West Virginia. Imagine that. It was like I was someone who had missed the dress code, wearing the only black suit at the wedding.

Some jobs in prison are considered privileged or skilled positions, even though the starting wages are the same for all jobs. Starting pay is at nineteen cents an hour and can go no higher than forty-two cents an hour. Privileged positions can be defined as working around regular folk, or anyone who’s not assigned a number. “You’re a prisoner, a menace to society, a potential threat,” the logic goes, “so be grateful that you’re allowed to work so closely with civilians.” Those who show signs of militancy or pride will rarely get a job of this stature; you can get black-balled in the blink of an eye. As I walked through the medical department, being by Pete (the caucasian I was replacing) and my Puerto Rican coworker, I saw an abundance of evidence that testified to these unwritten rules. The Puerto Rican was all humor, easily influenced and ready to cater to other personalities on a whim. Pete was the more popular out of the two. He was a clean cut guy with an edge; he openly flirted with nurses and slap boxed with the male staff. I got the sense that he was looked at as a distant cousin who just happened to get involved with the wrong crowd. As for me, I was the guy with too much on his mind; I was so quiet it bordered on uncomfortable.

I never understood why

I could never see a man cry til I seen that man die.

Man cry

“That’s Mr. Levi, I go in there and bust it up with him from time to time to keep his spirits up. He’s dying.” Pete said this to me on my third day of training as we stood outside of Mr. Levi’s cell.

“Dang…, from what?” I asked with added enthusiasm. By now I’d realized how to stroke his ego. The more I feigned ignorance, the more he spilled about the intricacies of the infirmary. I looked inside the cell and saw a black man who seemed to be in his early sixties at the oldest. He sat up in a hospital bed covered in a blanket from the stomach down wearing glasses over a pair of bright eyes. I sized him up and didn’t notice death anywhere.

“He’s got stomach cancer,” Pete answered after following my eyes. The infirmary has twelve cells and, according to Pete, nine out of the twelve housed inmates were either dying or suffering from pre- existing conditions. “Be careful, he has AIDS. Seven cell has hepatitis, don’t go in there without wearing your Hazmat suit. You aint hear it from me, I’m not supposed to be telling you this.” His delivery was melodramatic, which made me question whether his concern was sincere or if he relayed this news just so he could feel important. “I got you,” I responded. He continues his spiel.

It wasn’t long before I felt like a project or challenge to the staff. How long could I ignore their humor, all wisecracks about race or homosexuality? There was no balance, no middle ground; it was either one or the other. My Puerto Rican coworker was called Mexican on the daily in a joking manner. Everyday he was told his favorite lunch was being served, tacos or nacho grande. “There’s my favorite girl,” they would say to Pete, and he would comply by grabbing his crotch. I noticed the staff cut their eyes at me after every joke to evaluate my response. Searching for a chuckle, a forced smile, anything that would signal the okay for them to joke with me in that fashion. Tension grew as I ignored them, but oftentimes, tension is necessary to breed respect. I was left out, perceived as uptight. Rooms went silent when I walked in. Weeks of uncomfortable silences went by. I can’t recall the exact date, but I’ll never forget how I felt the first time I smirked at their humor. It felt like I was chipping away at a part of myself, like I knowingly stepping in the wrong direction.

Because there’s no way you can fight it

though you’ll still try

And you can try it til you fight it but

you’ll still die

The first time I walked into Mr. Levi’s cell, my sense of him changed. The air was stale and musky and his eyes seemed distant. Maybe death was near. I regretted the thought as soon as it entered my mind. I greeted him with a whatsup, man and smiled. He nodded and gave me that look black men give each other when we’re outnumbered. A quick search for camaraderie and assurance, the cornerstone being steady eye-contact. The ice was broken by this silent pact.

We talked and he never spoke of death. He spoke of life. The foods he used to eat and the dishes he wanted to try. His favorite station was the Travel Channel; Mr. Levi’s body was captive but his mind wasn’t. We reminisced, laughed, argued and repeated the cycle all in a week’s time. I shaded the bubbles on his commissary sheet for him while trying to influence him to eat healthier. He held firm like an old man stuck in his ways. The fire was re-ignited in both of us, and Mr. Levi gave my job meaning. Cancer had a fight on its hands.

Mr. Levi’s condition limited his diet; he had to eat a lot of ice cream, and despised this. I sat under correction officers who complained when he asked for his ice cream on time. They prayed on his downfall as if he was too much to put up with. I was offered his ice cream while he pressed his button with all the strength he could muster. I was frowned at when I requested his cell be opened so I could clean, and spied on if I lingered too long. Cancer had recruited some teammates and I wanted Mr. Levi to know it. His spirits remained high, especially after visits from his sister and brother-in-law. They were only allowed to stay an hour, much shorter than the six hours allowed for prisoners in general population. The more difficult his stay, the sooner cancer would win its fight. That was their logic. The staff declared war for purposes unknown, as if a deathbed wasn’t enough.

I hear you breathing but your

heart no longer sounds strong.

But you kinda scared of dying

so you hold on.

And you keep on blacking out and

your pulse is low.

Stop trying to fight the reaper, just relax

and let it go.

I was the basketball star Dwayne Wade’s twin; apparently, I also resembled Chris Tucker and a few other brown-skinned celebrities. You know we all look alike–those were their exact words, of course. I began to justify laughing at their jokes in order to keep our relationships cordial, but underneath it felt like I lost a layer. I fell for the divide and conquer tactics like so many before me. The flame inside me dimmed; my spirit took a major blow. That evening Mr. Levi and I discussed race and media stereotypes in contrast with our current surroundings. As our conversation ended, he told me to ‘be careful,’ as if his intuition gave him x-ray vision.

Mr. Levi’s pride wouldn’t let him beg for ice cream. If he was asleep when meals were served, or couldn’t get it down at the time, the ice cream wasn’t stored; it was thrown away or offered to us. He increased his snack consumption off of the commissary even though it was bad for him and even ordered a flat screen TV. “It’s my money,” he countered when my hispanic coworker and I questioned the purchase. For a second I think we forgot his confinements. A cell, hospital bed, wheelchair and the inability to control his bowels or shower on his own. With that in mind, a plasma tv and ice cream wasn’t an extravagant bucket list.

Maybe I’d tolerated one too many jokes that day or suppressed too many thoughts. I could say I had a long day but that’s just an excuse. I was at a point where the best of me and worst of me were trying to figure out who I was. That’s how it feels when you begin to slip against the grain, defying your inner core. This particular day, Mr. Levi needed assistance. Usually, “assistance” meant talking with him, so I volunteered. Mr. Levi needed help penning and addressing a letter. I grabbed the notepad and sighed irritably while a corrections officer sat back and enjoyed the show. The letter was only three sentences, but I treated it like Mr. Levi wanted me to write his autobiography. I was impatient and disregarded his feelings. I read over his legal document aloud, and as he tried to elaborate I snapped. “Look man, I don’t need to know all that, just let me know what else you need me to do!”

“Forget it,” he snapped back but his eyes said something different. They were filled with anger and hurt, a familiar look that still haunts me. Chuckles floated in the background from the CO, who saw signs of victory. I think Mr. Levi saw death for the first time that evening, not in himself but in me, in the spiritual form.

Everybody’s got a different way of ending it,

And when your number comes for service then they send it in.

Now your time has arrived for the final test.

I see the fear in your eyes and hear your final breath.

“They say he denied the treatment,” My coworker confided in me after Mr. Levi slept through two of our shifts. “But I think they just told me that to be safe so I won’t say nothing. They don’t wanna treat him; they really want him to die.”

My brain raced. Why would he order a brand new TV and accept weekly visits from family, and then suddenly refuse treatment? Our final encounter was on continuous playback in my head. Days went by and still didn’t wake up. The staff peeked in on him like an exhibit. “Yup he’s still breathing,” they said, or “that old fucker ain’t dead yet?”

I observed from afar, hoping to get a shot at redemption. If only I could catch him awake to erase our last memory. I pursued this relentlessly and worked overtime to no avail. I witnessed his eyes do cartwheels, blinking slowly with only the whites visible for days on end. His body slumped and his breathing slowed. Perhaps he decided to let go at the same time I did, after our last encounter, when I let go spiritually. Mr. Levi’s final look at me adds weight to this belief. He passed on three days after we clashed, and I watched him cry before I watched him die.

Mr. Levi chose to go. Did I choose, too?

How much longer will it be til it’s all done?

Total darkness and ease be at all one

I watch him die and when he dies let us celebrate,

You took his life but his memory you’ll never take.

You’ll be heading to another place,

And the life you used to live will reflect in your mother’s face….

Make the choice, let it go but you can back it up,

If you aint at peace with God

you need to patch it up

But if you ready close your eyes and we can set it free

There lies a man not scared to die,

may he rest in peace

I still gotta wonder why I never seen a man cry, ’til I seen

that man die

Lyrics by Scarface

Song: I Seen a Man Die

1 Comment

Ro Rambus

May 10, 2025 at 7:15 pm🔥🔥🔥