That summer, around 1:30, 2 AM, I lay in bed, up on the third floor, with the house all to myself, watching Elliot Gould, who I thought was dead; until I saw him about ten years later, in the penitentiary, about to get murdered on a train track. He was on the beach, looking up the hill after the object of his desire; and, in a haze, I thought, He just like me. He would get the girl though – the grown woman – by doing exactly what my big homeboy Neaky told me to do. “Yo, you gotta stop hanging around Hop and my lor brother.” Yeah, Gould shook his friends. If I had been that smart, things would have went so different.

That summer, in 1985, I would turn fourteen in a couple of months and, if Slim thought he was spooling and unfurling the world like a yo-yo, I thought I was about to put it in, at least, a half Nelson, hit it with a haymaker, or shoot it from half court. That’s what I thought.

That summer, in West Baltimore, the blocks intersecting Argyle Ave. seemed to stretch to the ends of the earth. Routinely, I would visited by the feeling of being unable to cover them all, but that I had to. So I made my way up and down those blocks – shaking the bricks loose in some places – as if I knew it all like the back of my hand. Every airway, alley, stash house, and shooting gallery. The champions, barking bluffers, chain poppers, and fence hoppers. I made my way along those stretches, receiving greetings from my peoples, after arising around noon and, sometimes feeling, after taking in the sights and sounds, that it had all started without me.

That summer, me and my homeboy Hip Hop was in the car with Fat Ben. Fat Ben ran the recs in West Baltimore – Robert C, McCollough Homes, Murphy Homes, and Lexington Terrace. Hip had already committed to hooping with Ben. Me and Shorty Maine could still play thirteen and under, and this was the reason for the car ride. I wasn’t trying to hear it, and Hip acted as a buffer. Until, Fat Ben, who a couple of years before had said that I would come through the middle like the Pillsbury Doughboy after I said I would do it like The Doc, peeped in the rearview and asked, “Hey, big head, what you going to do?” I spent Ben, told him I had to holler at Shorty Maine. He had already hollered at Shorty, he said. “That’s good,” I said. “Now, after I holler at him, I’m a know what he talking ‘bout.”Juicy came on the radio – an instrumental spliced with a cappella version. Ben pulled up on Seven Corners and turned it up after spotting a neighborhood girl and calling her over to the car. I told Hip to tell him we wanted Airs to match our jerseys. Ben stuck a finger into the leg of her cut-offs, her coochie cutters. She kept looking into the back seat, even after telling her to pay us no mind. Shortly afterward, he asked, “Girl, when you goin’ to let me suck that pussy?” Hip guffawed. I elbowed him, gave him the eye to straighten up; while I looked serious and caught her looking in the back seat again. I wasn’t up to speed on that yet, and Hip might have been a couple months older, but I was the big boy. And I was taking notes, trying to see how Fat – Coke bottled glasses – Ben was wrapping this girl around his finger. She was one of the ones. And I just couldn’t figure it out.

That summer, just as I finished mixing it up, the old lady on the corner of Lafayette and Argyle yelled from her window, “I hope somebody kick your ass.” It shocked me. I had carried around enough rage to kill may father that summer, but not enough heart to swing on him. Which would have made a world of difference. Believe it or not, we still respected our elders back then. So the old lady’s testament hurt me. She was defending Shawn. “Pfff.” His name wasn’t even spelled the man way. But she ran me through and drained all my glory. All the oohs and aahs and Hip naming the punch that blackened his eye the “Dow” evaporated just like that. With eyes big and wet enough to see down in the street, and a voice as plaintive as it was loud, I told her, thinking she’d understand, “He tried to knock me down last year when I was on crutches. …tried to get me while I had a broken leg.”She’d turned away. The gesture was oddly girlish. Then she left the window, let the curtain down. But that wasn’t the end. I would eventually go about 9 and 2 that season. Even another rematch with Shawn, connecting two punches that landed so cleanly they sounded like smacks. He’d been boosted up by a previous challenger, that lame Paul “Monk Man” Caulfield. And, over the course of weeks, Hip teased him whenever he passed by. “D—, let me see your hand,” he’d say. And, “No. It was a left.” He would say after holding up my right hand. The eye was closed for a while. Then it got blacker, turned purpleish, blue, and green. There were even flecks of yellow, which amazed me to see. But then I thought about it and, though had never seen nothing like it, I knew, recalling when I’d thrown it that the effect didn’t scratch the surface in comparison with the anger with which it was thrown. So, in the end, that black eye wasn’t nothing to me.

That summer, oddly enough, for some lor dudes whose world revolved around the peel, we didn’t play a lot of it outside game days. Had we out grown playing in alleys on crates? Ah… Fuck no! The recs were closed is why. Shorty Maine and my coach for the Project Survival league ran us like horses in practice. So practice was b.s. Suicides to start. To end. Laps at the end of everything for missed lay ups and free throws during practice. He was a cream centered sweetheart compared to Hip Hop’s coach who made them stand under the basket after missed free throws. So the next shooter’s ball would land on their heads. “Don’t move!” He told them. He wanted them to see where the ball was suppose to come through. Missed lay ups, failure to box out, traveling, turnovers – any of these violations could get the offender hammered in the chest or solar plexus. I wondered how he expected them to do anything with arms bruised and swollen. And, it was during that amazement, he told me and Shorty, “Y’all wait outside for Pie(face).” That was Hip Hop’s other name.

That summer I found out how much Hip Hop loved me. How unrequited it was. Why did I still harbor ill feelings about having to pants rub with Nicky, and not Boo Boo, after I told him that Boo Boo was mine, when we were eight and nine years old? Shorty told me when, not having seen Hip all day, we stood at the corner of his block, on Lafayette and Myrtle, waiting for him to appear. Me and Shorty had gone to VA that day, to play in a tournament that supposedly Bird and Magic had played years before, according to one of its hosts. I can’t remember if it was Falls Church or Church Hill, VA, but I remember they were the wackest people I ever saw in my life. The tournament was for three days. Our coach Flash had hinted at it, but didn’t want us to get our hopes up. Because neither he nor some of our parents had money to spare. Enter Mike “Millions.” Mike McMillan from down the building. He bank rolled the whole thing, which turned out to be a big disappointment for everybody. Everybody but Shorty Maine, who was given the MVP trophy of the tournament though we exited the very first game. Those people cheated the shoes off us. Literally. They had some kind of finish on the parquet to make it slippery. They would spray the bottom of their shoes to give them grip before each of them entered the game. And the ref went nuts with the whistle. It was so blatant and shameless that, after a while, all Flash could say was, “Play through it.” Which everybody tried, but only Shorty could. They had one black dude on their team. He was their best player, and he wasn’t nothing. Country-er than a farm with cows and a barn with a windmill turned by a stream. And Shorty burned him up. He couldn’t put the ball down on Shorty, couldn’t guard him, couldn’t do nothing with him. As bad as they cheated, we kept the game close. Shorty did. And we might have prevailed if I’d help deliver a one-two punch. But it was just Shorty. And after a hard, get even foul on Country – for sliding Shorty through the paint – Flash sat me on the bench, where I spent nearly the entire game. I had been so flustered, unable, too sensitive to get past what they were doing. Which I had never experienced during a basketball game.

That summer, I bought my first records. B sides, mostly. Shan’s was about Marley, LL’s about Cut Creator. Sometimes with – sometimes without – the aid of a joint, I free styled to the instrumentals. Saying rhymes I couldn’t retrieve for all the money in the world. Hip and Shorty loved it. Sometimes they begged me. Freddie Jackson, Sade, young Whitney Houston – they were some of what was on the radio. Day and night, though, every couple of houses you passed, every car that pulled up or rode by could be at a different point in the song. Lisa Lisa had shut the whole thing down with what was, still is, the ultimate tease song. The definitive anthem, rock, playbook – whatever – that every one of them was using to… shut the whole thing down with any attempt to move beyond kissing and feeling. You know, and I was sick of it. And I know I’m not the only one. Because a dude came out with a response – stringing together a bunch of soap operas – to kill that noise. Bring the curtain down on all that drama.

That summer I was shopping like a bitch. Take that however you want. But I had no idea about the concept of saving money. I had so much… stuff. I didn’t even need school clothes. My t-shirt game had come out like syrup. I had a white New Balance triathlon joint, with the swimmer, cyclist, and runner across the front. “Where you get that?” I had an ultra dark blue joint with the Cleveland Indians mascot on the front. No words. I had shells in flavors – no red, blue, green, burgundy, black high and low. I must have brought the black high tops about three weeks in a row; just cause they were cheaper in one store than in all the others. I had the burgundy suede Pumas, the blue ones. I had some light grey 576 New Balance that Hip gave me that I saved ‘til school started. I had the white high top basketball New Balance with the spongy sole and coated leather that glowed at night that I hooped in. I had the ellesse – was thinking about the Mizzunos, for a long time, but couldn’t get past them being iffy. I had the all black Nike Cortez and Avias. I wore them when it rained. Then I hit ‘em in the head with the track Avias that was light up gray with the charcoal emblem. Tylan would have messed them up if I didn’t take them off before he put me in front of the hydrant. “You going in there with the rest of the kids,” he said. “Stop playing, Ty. I’m dirty. …well, set that with your shoes, too.” I was a fool with it. I could’ve went toe to toe with Imelda Marcos that summer, and made a Calvin commercial with Brooke Shieilds. Plus I gave ‘em the stone washed charcoal gray Sergio Valentes, and came down there in the stone washed rust colored Bill Blass that looked like they were suede. I had everything the big boys had… except some big blocks, a dookey rope, a car, house, and a few experiences. I knew I was on my way though, cause a couple of them was asking me, “You think you the shit, don’t you?”

That summer, I sold weed for Narcy. Short for Norris. Narcy was a knock-out artist. In short, Narcy was a slick n— and came through the strip in slippers. He had the full length burgundy mink, and was thinking about letting me wear it to school that winter. Dunbar was a fashion show I told him. “No… No. But you can’t wear the mink without the tool,” and he wasn’t giving me the tool, “‘Cause, you crazy. And if they try you you might not give it to ‘em. And all I will think about is they killed my lor man and I’m the one that gave it to him.” So he gave me my first piece of (gold) jewelry – a pinky ring set with a red stone on top and two microscopic chips set on each side. He was also trying to give me the game and, being who I was, I didn’t receive it when and as I should have. It was on my way to see him that I stopped off at another friend’s house. And, wouldn’t you know it, he and his older brother were bagging up weed. Big Bruh had tossed a joint across the room, thinking I wanted to smoke. I mean when didn’t I, but seeing the mountain spread out on newspaper, I was thinking dollar signs. My light was on sometimes. So I asked for some again and he looked at his little brother, my friend, Lou, who said nothing then told me to come over and take some. “Yeah, Charlie, you know I got the clientele down on Argyle…” A fiend had come through looking for some boy, the hard stuff, and Big Bruh swoped it out with him. As I stuffed my gold paper bag too full to close, bobbed to music and squinted to keep the smoke out of my eye – I was thinking, Big Bruh going to give me some of this weed. “Charlie,” I said to him, “I want some to sell.” He whispered something to lor bro that I didn’t catch. “Some to sell Charlie. Some to sell,” I said. “Hinh? You didn’t hear me?” This set him in a rage. He turned on lor bro. He called him a punk, said he didn’t like his style. I was preparing to leave when Big Bruh came from behind the table, sat next to me, and pulled out a bill full of the hard stuff. He sniffed and told me to roll more weed. “Naw. Let him bag that hit hisself,” he said. “The shit huff anyway.” Then, “Yo, that’s his shit.” To which I immediately responded, “Boy, you got all this weed and wasn’t going to give me none…” Big Bruh looked at me, called Lou a punk again; then, a little sissy. “Going to let him ask me for the weed all them times.” Lou told him he was going to give me some. “He say something else,” Big Bruh said, “I’m a put my hands on him in here.” A little while later, I left with about thirty bags – sixty forty. It was in fact huff, but I sold it all. Along with what I got from Narcy, which was always what it supposed to be. I had thrown them all together. The purchaser chose which yellow bag he pulled from the big brown one. Later that night, maybe a little before one, when I went to give him his money, he was sitting on the steps with one of his skanks. I can’t remember if she was the one he needed a shot in his ass from the free clinic for, when we hooked school and went up 1515. Or if she was the one he needed the ointment for, when his father shook his head and said to me, in amazement, “D—, this n— got the crabs.” But I’m glad Big Bruh wasn’t out there when I brought him the money. ‘Cause he was acting country again. I had stopped a couple of stoops from his, and motioned for him. One of the first things you learn from the gangster movies is to keep broads in the dark about business. But he wanted to show off, and asked from where he was seated, “You got my money?” I pulled out my knot, and asked, “What I owe you?” …to the amazement of his lor biddie. He was surprised, too – by the amount that went back into the pocket of my BIKE shorts. He stood to put the money in his pocket, stepped down and shot an imaginary jumper. Lou was nicer than all of us. He bumped heads with Sam (Cassell) over Madison that summer. He asked if I wanted some more work. I started to tell him it would eff-up my clientele. But told him I had to get off the rest of what I had. We smoked two joints of it between the three of us, and I left them zooted. I walked home in a contemplative mood, with the distance expanding between me and Lou, and I thought about all of my friends. A few times I looked back to see if they had gone inside yet. After the joint, she looked like she wanted me… to stick around but, even then, I didn’t like those kinds of girls. I continued my contemplations, still, for the most part, clueless as to it all. Unable really, to nail down anything. Looking back, as the only eldest among my friends, everything was trial and error while mashing the peddle. And I need a calculator to count how many times I hit the wall.

That summer my father would swoop down on us like… Naw. ‘Cause we wasn’t no pigeons. You know. But he would turn up out of nowhere and too fast to slip him. I was really tired of him though. And I was ready. So I asked Hip and Shorty, “If I pop him, y’all going to help me? I’m going to pop him first…” But Shorty, like the punk that Hip told him he was said, “I ain’t hitting your father.” And it was on one of them days, just after telling Vietnam he needed another dollar, I wasn’t taking less than four; he turned up like he did. Before I could hide my ring or pass my cash off to Shorty. The clothes and tennis didn’t really look extravagant. I stayed fresh. Moms had even kept me that way. But with the weed money and boosters coming through the block, it went up a couple notches. Though he no longer saw me every day, in an effort to corner me, he made an issue out of the gear, too. The ring, I told him, had come from a bubble gum machine. “Go over Upton and see what kind of stuff they got in there.” Then, after saying a second time, “Naw. I ain’t trying to hang out with you. Me and my boys on our way to the movies,” Vietnam came back waving four dollars. And after telling him a couple times, I didn’t have no weed; my father looked at me and hold him, I’m trying to talk to my son. Then, he told me, “Let’s go.” I thought about my stash the whole time I was with him. Angie Bofield… Meyerholf… I was thinking, even if Hip smoked some, Shorty wouldn’t let him go crazy. So I focused on getting this over with as fast as possible. We were headed down town. When we got there, we went in Bernard Hill’s and bought a tie. Then we walked a couple blocks to the Inner Harbor. And for the three, four, or five hours I was held captive, he talked as much about how much he loved me, my mother and sister, as I thought about my stash. So he was out of the house, but not quite out of my life.

That summer, Shorty told me that Hip said if none of us make it, he was going to buy us a house. We would eat subs every night and fuck our bitches. It sounded like an amazing life. I looked forward to it. Hip would make it happen with the nineteen–thousand–dollar suitcase he got when he turned eighteen. Hip had been hit by a car when he was six. The car broke his thigh, which was mended with pins and left him with a limp. That and the dance he did to the song that started with his name is where the name came from. I asked Shorty what he said about his mother and sister. Shorty said he told them that’s what he was doing with the bread. I didn’t doubt it. Hip was generous like that. Which is why I thought he might be mad at me about the day before, but Shorty assured me he wasn’t. I still felt bad though. They had been about to walk down town to buy wrestling tickets – which is probably why I wasn’t in on it. It was kids’ stuff. Like the pigeons they got from Fleets. Constantly looking each bird in the eye, itching to claim it a diggy moe that would infect the coop so they could pop their necks. Or the horses I once gave them money to rent from the A-rab stables. Those big funky animals they had so much fun riding – making the horses leap cars, cackling with laughter as the animals’ hooves slid in the street. I found it bizarre seeing horses in the concrete jungle. I was going to the movies. Lou told me it was this movie I had to see. They were popping so much tool, I would love it. “Yo, that’s it right there,” I told them, spotting the marquee with Year of the Dragon about a block from the Civic Center’s ticket booth. I tried talking them out of the wrestling tickets, telling them they know it’s phony. They were lor boys. To come with me, push come to shove, we can come back tomorrow and buy the tickets. It was early in the day and I hadn’t sold any weed. So I only had enough to pay one of their way into the movie. The tickets wouldn’t be on sale tomorrow, they told me. I told them to decide amongst themselves who was going in with me. Then I gave Hip a joint to keep him company back uptown. It was the start of something. I watched Mickey Rourke in what may have been the germination of my fetish – if you can call it that – for journalismtic….

That summer I received three pieces of mail. Two from the post office, and one was hand delivered. One informing me that I was being accepted to Dunbar. One informing me that I was loved by a girl who must have listened to Lisa Lisa upon arising, in the middle of the day, and again before bed. The last was from the girl I slept on, delivered by her friend. It informed me that the sender would blow me like a stick of dynamite, and saved my life the first time later that fall. With details as vivid and adult as the box of VHS tapes Lou and I watched on the VCR sent by his brother stationed in Beiruit the summer before. Oh if I had known you go with the ones that went for you.

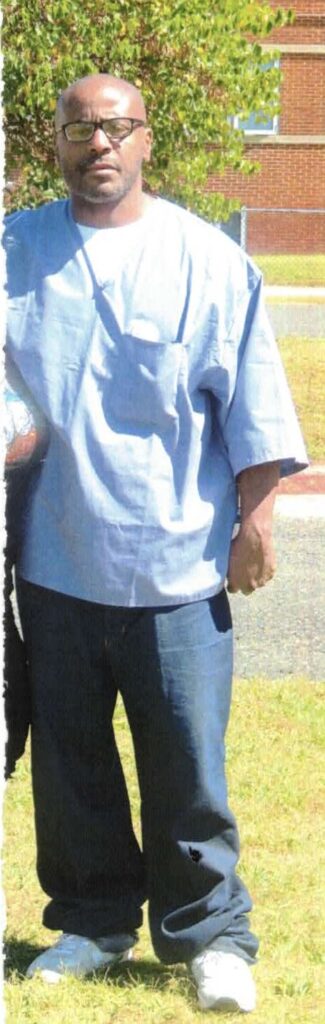

That summer, I remember so well because it was the last one I spent in the street. Thirty-five years later, as a fifty–year–old man, the parole peoples told me that I was still young. After all those years. So, who knows when they’ll be through playing with me like that.

That summer, if I had known… that life was sometimes like art – you could pause, or flat out stop. You brush it off here, smooth it out there, and carry out something good to where it would take you. You could leave it alone; try something new. Or, I could have learned that life was nothing at all like art – try all you want and, even if your teenage heart stands still, it won’t freeze a second time. You’ll live it once, maybe revisit, reminisce about it. But there will be no make-ups. No do-overs. You can roll the dice with: Can I taste those lips? See if it rings false. And all the people and frenzies that filled your young life won’t be examined, exhausted, in short order. Or maybe even a long one. Though they were there, and will remain, dead or alive, lingering like ghosts. The lamest claiming to deserve their due. But I know which start like my Legends of the Summer.

No Comments