By Jeremiah Bourgeois

A few years ago, when one of my lawyers was reviewing the numerous disciplinary incidents I’ve been involved in throughout my confinement, I recalled a maxim that I had recently come across: Brutal conditions breed brutal behavior. That resonated with me. It explains so much of my life. Those words again came to mind when, shortly thereafter, I learned about a man scheduled to be executed in Texas.

He was born in 1979. He received a life sentence when he was 15 years old. At 16, he was sent to an adult prison. There, he was accused of killing a man four years later. For that, he was sentenced to death. His execution date is now set. 28 April 2015. As I write this, he’s likely spending his last days on Earth.

While my familiarity with his case is limited, I can easily deduce the trajectory of his life from the time he was arrested for murder when he was 15 years old. He was tried as an adult, likely labeled a “super-predator,” and sentenced to life because taking his life was constitutionally prohibited due to his age. Then, instead of sending him to a juvenile facility until he reached adulthood, he was sent to a high security prison, to sink or swim amongst older, hardened convicts. If his crimes did not have any sexual component, and he didn’t snitch on any co-defendants, he was probably embraced by a group of guys who seemed to have his welfare in mind. Yet the measure of protection afforded by such camaraderie ultimately comes with a price tag: meting out violence for the cause, be it racial or gang related.

Violence, and the threat of it, would have defined his teenage years in prison. Using it under these circumstances is often a matter of self-protection. Brutal conditions breed brutal behavior. Trust me, I know first hand.

I was transferred to an adult prison when I was 17 years old. There, I was embraced by Gangster Disciples because a high ranking member who befriended me on the streets was confined at the same facility. While I wasn’t under any explicit obligation to join in their battles, I knew the deal: if violence erupted and they needed me, I’d be there with the rest of the soldiers. Aside from that, I still had to ensure that I handled confrontations in such a way that my reputation was always preserved. To allow someone to disrespect or take advantage of me would have done more than remove the Disciples’ shield. Where countless men lie in wait for the opportunity to strike, and countless stratagems are employed in order to socially isolate a victim, allowing someone to harangue, extort, or assault me without a swift and violent response was (and still is) the surest way to invite more of the same.

So I stayed prepared for violence. It worked out well for me in the end. I was never extorted or molested. My wounds never required outside medical attention. My life will not be defined by crimes committed when I was a kid. 21 December 2017 I will likely be set free.

I am so fortunate that stabbings are rare in the Washington prison system. Here, brawling, blunt objects, and boiling liquids are typically enough to settle matters. In many prisons across this nation, stabbing people is what violence entails. A prisoner, especially one who is young and untested, often has to demonstrate that he is willing to slice and stab in order to live unmolested in general population. Otherwise, he can live permanently in segregation for protection, isolated in the same manner as prisoners segregated for committing acts of violence in general population. This is the reality of high security prisons. What distinguishes one prison system from another is the level of violence and the methods employed.

I am so lucky I wasn’t in Texas. The conditions were bad but comparatively not brutal. The threat of violence was indeed real but the violence itself wasn’t homicidal. During my first decade of confinement, violence was my primary means of dispute resolution. I spent the majority of that time in punitive segregation. I did not distinguish between prisoners or prison guards, and have a consecutive sentence to serve for assaults on the latter. The reason that I have a release date instead of an execution date is simply because knife play does not define Washington prison culture. In Texas, prison conditions are brutal enough to breed deadly behavior.

So here I sit in general population for crimes committed when I was 14 years old. He was probably doomed the moment he set foot in that Texas prison to serve a life sentence for crimes committed when he was barely a year older. I’m going to be given the opportunity to demonstrate to a parole board that the threat I posed to public safety is no more. The man he has become after 20 years of imprisonment is of no import. 21 December 2017 I am set to be freed. 28 April 2015 he is scheduled to die.

This man has been convicted of terrible things, as have I. But let me highlight the Supreme Court’s View of my original life without parole sentence, for it is salient in his case too. Giving a 15 year old a life sentence “precludes consideration of his chronological age and its hallmark features—among them, immaturity, impetuosity, and failure to appreciate risks and consequences. It prevents taking into account the family and home environment that surrounds him~–no matter how brutal or dysfunctional. It neglects the circumstances of the homicide offense, including the extent of his participation in the conduct and the way familial and peer pressures may have affected him. It ignores that he might have been charged and convicted of a lesser offense if not for the incompetencies associated with youth~–for example, his inability to deal with police officers or prosecutors (including on a plea agreement) or his incapacity to assist his own attorneys. And finally, [it] disregards the possibility of rehabilitation even when the circumstances most suggest it.”

Those are the words of the Supreme Court in the 2012 case of Miller v. Alabama. Those words changed my life. They came too late to change his.

As for the death sentence imposed upon him, it is all too easy for me to figure out the gist of the prosecutor’s argument: “Ladies and gentleman of the jury,” I can imagine her saying with an earnest look and impassioned voice, “This man began killing in his early teens, and time has demonstrated that no sentence other than death can keep him from killing again.” On its face, this is a persuasive summation. However, the suasiveness of such an argument rests upon the premise that 20 years of a man’s life can establish that taking his life is justified. I reject that notion. I know too many men confined for heinous crimes who are the antithesis of their former selves. I’m one of them.

I’ve done terrible things. Yet the man I’ve become after decades of imprisonment may alter my future. All too often, reform is irrelevant and will do nothing to alter one’s fate. His execution date is set. The man he is today is irrelevant to the State.

|

| Jeremiah Bourgeois 708897 Coyote Ridge Corrections Center P.O. Box 769 Connell, WA 99326 |

3 Comments

Peace4us

November 20, 2023 at 12:54 pmYou are so wise and have much to offer this world of ours.

Tayo&Roguie

April 29, 2015 at 2:04 amHi Jeremiah, what a moving story. I really enjoyed it. By now you've probably heard that the inmate you were referring to got a stay! It's great news. Wish it were more often that we could say this. Very happy that you're getting out soon. Wish you all the best!

A Friend

April 26, 2015 at 12:23 amA reader from Australia asked me to post this comment on her behalf:

I agree – where lies the sense or justice in giving a child a death sentence? I believe with all my heart that the person you're referring to is innocent – and his innocence should be relevant to the State.

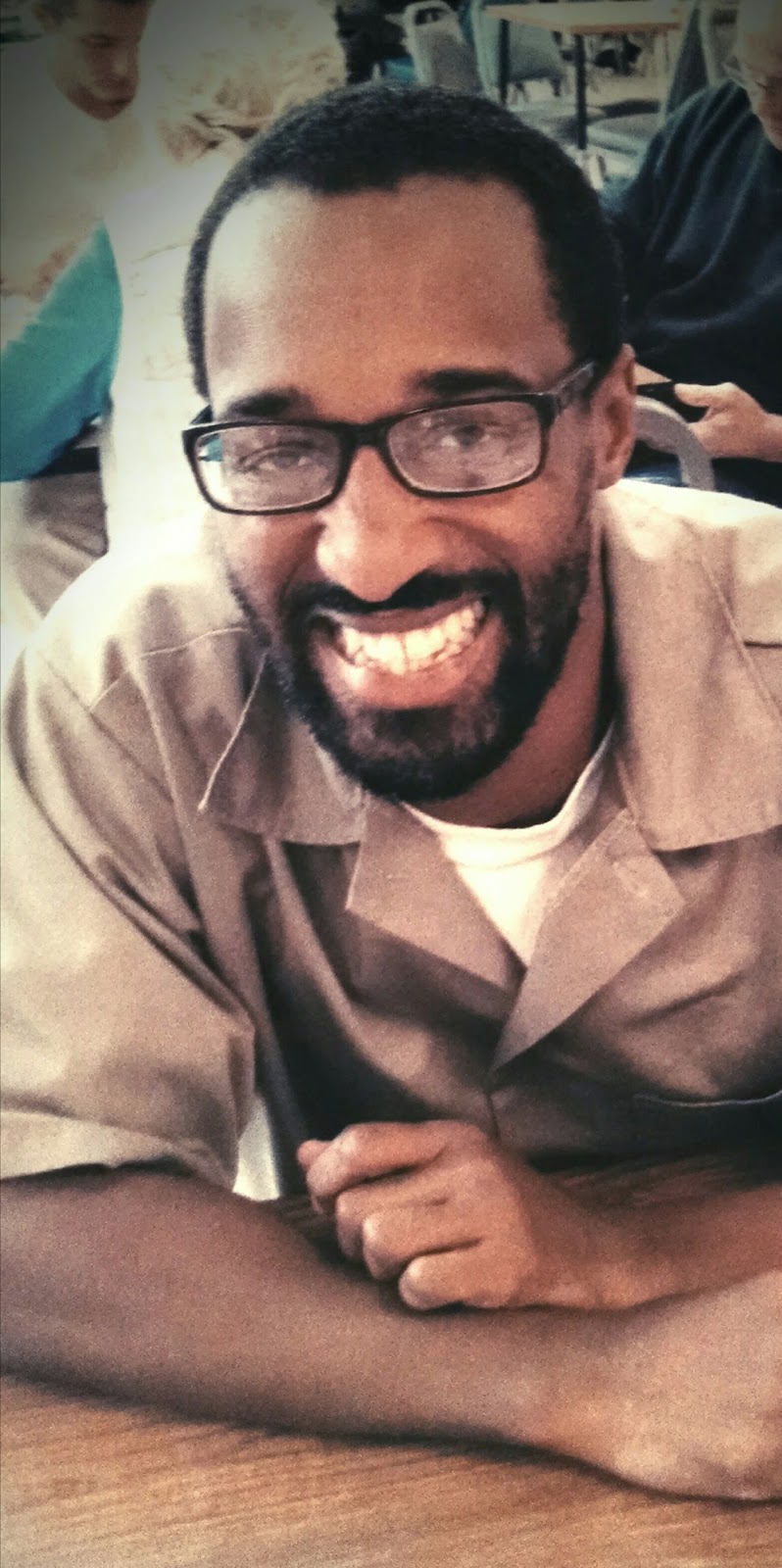

Almost twenty years after being sentenced at 16 as an adult, he is a fine human being; one I'm very proud to call my friend.

Best wishes for your future Jeremiah. – Heather