The news isn’t all bad. What I’m referring to is the news from the parole board. As I mentioned in my piece called Parole Board Experiences, men and women can overachieve prior to their parole hearings and yet they may still be denied parole. Societal presumptions and narratives pushed by the news often create stiffer stipulations for men and women faced with seeing the parole board. What occurs outside of prison doesn’t always dictate decisions that determine whether freedom will be extended to someone at the parole board, because some men and women complete few requirements and may still be granted parole. But, despite all this bad news, the chances can be in the lifer’s favor, believe it or not. It all depends on the change and the work that’s placed into what they seek.

I’ve often heard from men who I’ve done time with that, when the subject of lifers being released is broached during an event they’ve attended within a prison institution or a community event hosted by activists, a speaker who was once a former parole board member or a highly ranked prosecutor would proudly proclaim, seeming to intentionally reduce hope to mere grains, that men and women serving life sentences (eighteen-to-life, twenty five-to-life, five-to-twenty five, etcetera) don’t have a right to be released on their parole dates, that their sentences are definite, that their release is more of a privilege. Unfortunately, this is true.

Nonetheless, the news isn’t all bad. Men and women who demonstrate an extraordinary change in their character are often afforded this privilege.

In “Parole Board Experiences,” I went around the prison where I’m currently located and gathered conversations surrounding experiences men had during their parole board hearings. Each man was given more time. Their new sentences ranged from two to ten years. Some men expressed bewilderment, while others accepted their new sentences.

For me, hearing about someone I did not know being given a parole after serving a life sentence used to seem like a myth. I thought that the chances of it happening was comparable to shooting a spitwad back into a straw, that’s how rare it was. But over the past two years, that mythological air has diminished as I’ve heard from men, moments after their hearings, that they were granted parole.

Recently, two men that I’ve come to know shared with me that they were granted parole. As I see these men now, a noticeable strain has been lifted from them. No longer do their forehead wrinkles demand attention before their eyes, nor do they walk with hunched shoulders. The bleak scourge of serving a life sentence does something to a man over time, but the reward of freedom and redemption makes a huge difference.

The two men I had conversations with were Dan and Toney. The men had different emotions about their newfound freedoms, but shared a glow I witnessed in each of their eyes. It was hope, excitement, and anxiety.

Dan was the first of the two men I held a conversation with. We spoke to one another occasionally, often in passing or about sports, but we also have a kindred connection because of our spiritual relationship with God and the struggle to get through hard times. We understood the battle of male toxicity, so the grouchy and emphatically furrowed eyebrows and face wars were kept some other place.

I caught him on the walk path. A jovial smile had breached his elastic, senescent cheek. The smile was like a magnet drawing me in, I had to know what he was smiling about.

The visor of Dan’s hat was turned up, as well as his prescription brass-rimmed glasses which hugged his pale ginger face. “Hey, Terry,” he said when he noticed me meeting him in stride.

“What’s happening, Dan,” I said. It was more of a question. He kept grinning, and somehow I acquired a grin, too.

“What’s going on, man…”

“You and that grin. Keep on, people gone think you were given those be happy pills.”

He chuckled at the humor. “I was given something, but it wasn’t any pills,” Dan said. He glanced at me, then faced forward as we continued onward. “Can you keep a secret?” he asked mysteriously.

“What is said here stays here with us,” I assured him. Although I share what he told me in this piece, I never shared it with anyone else.

“I had my full board hearing today,” he said, looking around to make sure no one else was listening. The closest person to us was almost thirty yards away and way out of earshot. When he was satisfied with our privacy, he continued. “I was granted parole. My out date is in sixty days.”

I stopped and stepped to the side with a grin. I now knew the reason for the smile. Dan stopped walking also. He was in his late sixties, but as he shared the news he seemed to look twenty years younger.

“That’s great news!” I said.

“I’m still in disbelief.”

“I don’t blame you, I would be, too,” I told him. “So what’s a full board hearing?”

“A full board hearing is where the final decision is made to determine if a person is granted parole or not.”

My puzzlement couldn’t be suppressed. “I thought there was only one stage.”

“There’s actually three. You have your COBR (Central Office Board Review) hearing. If it’s asked for, there’s a public board hearing, and finally, the full board hearing.”

“What’s a public and COBR hearing?” I inquired.

“A public board hearing is requested by the public. This typically includes the county prosecutor, the victim or victim’s family, and probably a community activist.”

I shivered. “That sounds intense.”

“I heard it is. Fortunately, I wasn’t called for one. And COBR hearing is a Central Office Board Review.”

“What happens at that review?” I asked, although I was already picturing participants of such hearings in my mind.

“With this hearing, you go before people over at the Department of Rehabilitation and Corrections. They’re the ones who recommend you for a full board hearing.”

“Sounds like a serious task to complete before being considered for parole.”

“Believe me, it is. But it’s doable. My advice for anyone going before these boards is to just be themselves and show how they’ve changed.”

“Well, it was great speaking with you. And again, congrats on getting your parole. I’m proud of you.” I knew he deserved it.

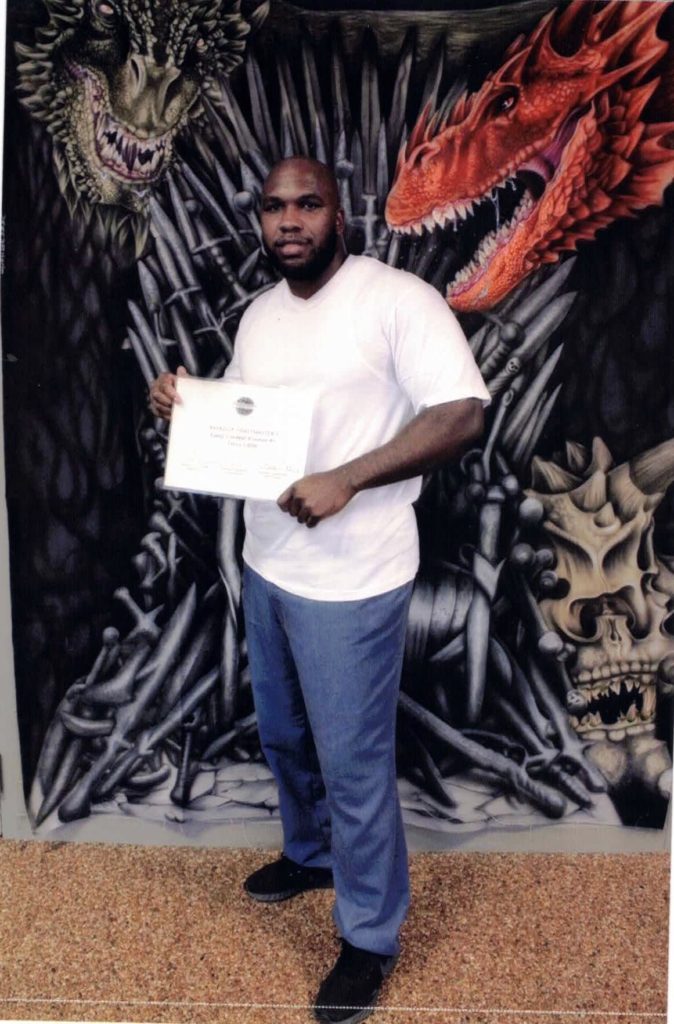

The next conversation I had was with Toney. Even after thirty years of incarceration, he was one person I’ve known to always remain hopeful, hopeful that the effort he put in would gain him the opportunity to acquire his freedom at the parole board. From year-long programs he’d taken with great hardship to a myriad of pro-social activities, he remained steadfast in achieving the ultimate goals: bettering himself, and being granted parole.

Toney walked the compound every morning around 8:00 AM, circling the confines over twenty times until he either tired himself or until the yard closed. I caught him early on his walk one morning, listening to music, appearing to be deep in thought or maybe trying to make a beat in his head. He considered himself a musician. There were many rappers in the institution, and Toney had made beats for many of them. Making beats is something he prided himself on. Nonetheless, he was prudent with who he dealt with.

It was the very beginning of winter. Toney was gloved and layered in clothing, the forty degree weather having no effect on his routine. As I approached, there was no need to beat around the bush. I knew he’d been granted parole; it was the talk of the prison, he’d told everyone the news.

“Would you believe that just two years ago I was talking to you about getting that two years at the board?” Toney said, minutes into our conversation.

“Yeah, you said it felt like you were resentenced.” I recalled our past conversation. It wasn’t one you could forget.

“Yeah, but unlike the last four times I had been flopped, things felt different two years ago. I was given suggestions on what programs I should take; the board actually stared at me, and two members even smiled at me. And this time I had a ton of faith in God.”

“Sounds like you found peace when you went up two years ago,” I said.

“I had no choice. There must have been something the board saw in me last time for them to give me two years. I suppose they knew like I did, that my work on myself wasn’t finished. I think this last time I went up, though, they noticed I straightened out all the crinkles in my act; they gave me a five to zero vote.”

“Five to zero…” I stared at him curiously. “What’s that?”

“That means that no one opposed me being granted parole.”

“Wow, bet that affirmed so much for you.”

Toney chuckled. “It did.”

“Tell me, what does it feel like?” I asked.

“What do you mean?”

“Freedom after thirty years?”

Toney dropped his head, then came back up with a pure grin. “If I had to describe it… It feels like sitting on a sturdy cloud.”

These conversations caused me to reflect. I thought of the many people who would come after these two men, the many who would be granted parole and the many who would be denied parole. I thought of the men who would walk through these doors burdened with uncertainty as to whether they would eventually be released. I thought about the people burdened by crime and what they thought about parole. Nonetheless, I was hopeful about the entire process. Until next time…

No Comments