Read earlier parts of this series here.

The arrow of time wobbles a bit in solitary confinement. There are days that feel like months; hour upon torpid hour of men seemingly frozen in the act of screaming at each other, kicking their steel doors, lighting bonfires; minutes wherein the clock seems to forget it is tethered to entropy and only with the greatest of efforts manages to rouse itself to change the rightmost digit, before once again slipping back into a stunned somnolence; summer eons where we pour endless cups of water over ourselves and then lay on the concrete floor trying to ward off the effects of living inside what are essentially huge convection ovens. And yet, because almost nothing of consequence or interest ever happens, it can seem like the months just flew by, when you try to cast your mind backwards to a particular date or season. When did Swift go home? Wasn’t it in February? No, it had to be May. No, dude — it was November last year (and in any case, let’s bitch and hoe each other for an hour or two just to pass the time, until one of us can score some dope; vice, like all forms of degradation, can seem like an acceptable pastime if boredom is the only alternative). Calendars are vital. For years now, I’ve had a friend print me out each of the twelve months on a single sheet of letter-sized paper. I glue these together, three months by four, like one of those ‘At A Glance’ deals you’ve probably seen at Office Depot. I find I need to see time laid out this way, where all of the various discrete parts can relate to each other. Time gets fixed; because of the mass of notes I’ve scribbled on each date, I know what I did in April, and I’m aware of what came before, and what after. It’s a form of scaffolding, around which I build what life I can amidst the ruins.

The first thing you notice when you look at my calendar is the shotgun-pattern spray of colors: little squares neatly drawn onto the upper right-hand corner of certain days. Red boxes indicate execution dates; the names of the condemned are then followed with the word “stayed” in positive cases, or simply with a set of two numbers corresponding to the number of killings each year and the total number since the Gregg decision (5 and 583 in my subjective timeline). Blue boxes correspond to federal holidays. Green deal with administrative dates of note in my life; two each year for my State Classification Hearings, wherein gray functionaries get to practice looking befuddled about precisely why I’m still in solitary confinement, and then promise to look into the matter (but never do). Silver boxes signify birthdays or anniversaries of friends current and past.

You may not notice it immediately, but there is a single gold box, found on 20 May. This is the day Jeff Prible was granted relief by the federal court. On the upper left, atomic number position, is the number three; the years since that ruling. In the same way that you might mentally orient your present date to your birthday or Christmas in order to get a sense of how the year is progressing, I seem to have tethered myself to 20 May. In a rough sea of mostly meaningless moments, that day became a kind of harbor, lighthouse spinning, letting me know all hope wasn’t completely pointless.

And yet, time continued to do what it does. Weeks went by, then months, without any sort of update. I waited to hear about Jeff’s removal from the Row, his return to Harris County Jail. I sent him letters of encouragement, most of which were intercepted. In this world, friendship and solidarity are considered subversive acts, and any material expression thereof automatically classified as contraband. (And some people still wonder why it is so many of us take an antisocial turn as the years go by…)

The one-year anniversary of Ellison’s order was not a happy one. I kept thinking: Jeff was to have been retried or released six months ago. I wasn’t worried yet. That didn’t really start until we reached the second anniversary. By that point, I’d begun to wonder what exactly the Fifth Circuit was debating. The rat, so to speak, had been scented. I spent the afternoon of 20 May 2022 rereading the ruling from the district court, trying to view the factual landscape through the eyes of a far-right jurist.

I’m sorry to report that by the time the Fifth Circuit reversed Jeff’s relief in August of 2022, I had begun to expect it. It had just taken far too long and, for whatever reason, Jeff has never enjoyed any kind of widespread public support. Some cases are like that, and some aren’t, and there’s no real logic to it that I can see. The Fifth noticed that the newspapers weren’t championing Jeff’s innocence; they then ran their politico-juridical calculations and decided that the fall of Kelly Siegler was just too awful to permit. Hegemonies protect themselves. That’s what they do — that’s how they last. I really shouldn’t have been surprised. Cynicism may be very ugly but, man, does it sure seem to be accurate in my world.

Ellison’s order granting Jeff relief was 88 pages of erudite, dense legal analysis. The Fifth Circuit’s denial of that relief clocked in at 32. Sixteen of those pages — half the document, mind — was simply a rehashing of the history of the case. My intention when I sat down to write this portion of the series was to attempt to treat the Fifth Circuit’s reasoning with as much fairness as I could muster. Just because I disagree with someone doesn’t mean they are stupid or corrupt, after all. But I’ve been sitting here for several hours reading and rereading, trying to summon that whole counter-attitudinal argumentation technique that allows you to forcefully argue either side of a proposition, and I just can’t seem to manage it. I don’t think it is merely my personal biases at play here — I mean, I’m Jeff’s friend, so of course this is not the outcome I was hoping for. But I like to think I’m honest enough to admit it when the State has the weight of precedent or logic on its side. In those situations, I might, in the interests of what I consider to be a search for fairness, argue for extrajudicial considerations, or maybe take a deeper look at structural biases that seem to grant the State unfair advantages. I’ve done that before on this site, and I am in fact still alive to type these words because we successfully argued in favor of the existence of such factors. In this case, however, I don’t need to do that: Jeff has always had precedent on his side, and he has the reasoned position. It is the government that has twisted or outright disregarded case law to fit the desired outcome. Not only this, their arguments while performing these contortions are inherently quite shallow — these judges aren’t fools but their words are in fact foolish. There is a frigidity to their position that leaves me feeling unnerved, due to what this implies about the current politicization of the judicial system. I will explain this latter point in greater detail shortly, and I will be surprised if you don’t agree with me by the time we are finished.

Perhaps the simplest way to illustrate why I came to the above conclusions is to compare Jeff’s ruling to a number of cases with similar factual landscapes. I mean, that’s how the law is supposed to work; you analyze your situation, find cases of a similar type, and then argue that precedent requires the current court to behave in a particular fashion. (This is why I have repeatedly claimed on this site that the law is an inherently conservative subject of knowledge: it is always looking to the past for guidance instead of constantly testing, retesting, reevaluating, searching for verification and replicability — as science does, in other words.) Fortunately, there are two cases that make this comparison very easy: Banks v. Dredke and Strickler v. Greene.

Let’s start with Banks. As with Jeff, this was a death penalty case out of Texas, involving allegations that the prosecution withheld exculpatory evidence regarding two witnesses. Recall the basic outline of the story so far: Jeff was convicted largely on the testimony of Michael Beckcom, an inmate at FCI Beaumont, a federal prison, who claimed that Jeff had confessed to the murders he was charged with. We now know Beckcom was just one of a pack of inmates working together to manufacture a confession, and we know that Kelly Siegler was aware that this was happening — thus her suppression of the letters mailed to her office reputed to have been written by Carl Walker, Jesse Gonzalez, and Mark Martinez, as well as her repeated lying about the extent of her communications with Beckcom and Nathan Foreman. Had Jeff’s attorneys known about any of that, they could have impeached Beckcom’s testimony at trial. In Banks, the district attorney similarly failed to notify the defense of potentially exculpatory evidence about two witnesses, including one who turned out to have been a paid informant. Like Beckcom, this witness lied on the stand in ways that should have been obvious to the prosecution. As with Jeff, the federal district court reversed Banks’s conviction primarily using the Brady decision; similarly, the Fifth Circuit took this away, arguing that Banks was procedurally barred since he had failed to pursue the issue of the suppressed material in state court — the whole “you should have recognized this as bullshit earlier” theory of jurisprudence that the Attorney General’s office used throughout Jeff’s entire appellate process, a doctrine I’m afraid you will be on a more familiar footing with by the time you are finished with this article. Eventually, Banks was granted relief by the Supreme Court. Amongst the takeaways from Banks is that when prosecutors conceal exculpatory or impeaching evidence, it is incumbent on the State, not the defendant, to set the record straight. Of equal importance to the extant case is that the SCOTUS also ruled that a petitioner shows “cause” for excusing procedural default when the reason he could not develop facts at the state court level was due to this very suppression of evidence. You can imagine that Jeff’s federal district court had this case or other similar ones in mind when he overturned Jeff’s conviction. So far, so obvious.

In Strickler, prosecutors similarly withheld evidence regarding a witness, despite their claim that they had an “open file policy” which gave Strickler’s attorneys full access to all of their files — precisely what Kelly Siegler claimed in Jeff’s case, and which would prove to be one of her more bald-faced peregrinations from the lands of truthfulness. The exculpatory evidence in Strickler would later show that significant portions of the testimony of the State’s star witness were doubtful. Like with Jeff, the federal district court granted relief, only to have this taken away at the appellate level, this time by the Fourth Circuit. On appeal to the SCOTUS, Strickler wasn’t able to secure a reversal to his sentence, because the Supremes felt that he had failed to show a reasonable probability that his trial would have had a different outcome — another example of that politically burnished crystal ball that The Robed Ones sometimes use to peer into other branches of the legal multiverse. Of importance here, however, is not the outcome but rather the Supreme Court’s repetition that it is the prosecution that is responsible for providing any evidence favorable to the defense, including information known by the police. Any suppression of this evidence violates due process, irrespective of the good faith or otherwise of the district attorney. Most importantly, the SCOTUS stated that the nondisclosure of any documents is counted against the State if this behavior impedes trial counsel’s access to the factual basis for making a Brady claim.

These two pieces of precedent are not obscure. Both have been cited thousands of times in the federal registers: 2,537 for Banks, including more than 500 positive references (meaning courts relied on the ruling to settle cases); and 8,873 times for Strickler, including more than 2,600 positive citations. Neither has a single negative citation, according to LexisNexis. What’s that mean in plain English? It means you can see precisely why Judge Ellison granted Jeff relief on the issue of suppression: the man was using settled law that is not legally or morally confusing. It means that Jeff should have been able to rely on this history of decisions to be respected by reasonable judges. You can probably guess what the key word is in that last sentence.

Instead, the Fifth Circuit determined that Jeff had procedurally defaulted on all of his claims. Understand what this does not mean: it doesn’t mean that anything Jeff alleged about Kelly Siegler, Michael Beckcom, Nathan Foreman, or any other part of that whole rotten circus of snitches and scumbags, was untrue. It doesn’t mean he lied, or even that in a factual sense he didn’t prove his innocence. Rather, it simply means that they didn’t care about any of that. What they claimed to care about is that he didn’t follow procedure — that, in fact, procedure is more important to them than truth, more important than a government agent manufacturing false confessions, more important than human life. While Ellison meticulously divided the various pieces of suppressed evidence and tested each to see if it met the standards set in cases like those mentioned above, the Fifth combined them into a single claim, and then stated that Jeff should have alleged during his initial state court process that Siegler had used her informants in an illegal fashion. This is clearly wrong on both the facts and the law. We’ve already seen what District Attorney Vic Wisner said about conspiracies in Part 8, which is the natural position most of us have when some prisoner claims to have been set up. When Jeff began to piece together what must have happened during his state appeal, the Attorney General’s office stated, on the record, that, “we absolutely refute [that] there was a ring of informants”, even as the evidence for the existence of such was sitting in a file that Siegler refused to hand over to Jeff’s team. The Fifth Circuit claimed that Jeff “could have asserted the claims in his initial application and then acquired supporting evidence through state habeas proceedings.” They said this even though they are aware that Texas has a particular pleading standard for state habeas proceedings, which states that “conclusory allegations” are wholly insufficient, and applicants, like Jeff, must “plead specific facts which, if proven true, might call for relief” (Tex. Code Crim. Proc. Art 11.071, Section 9). Jeff didn’t have specific facts at that point: he hadn’t found Carl Walker yet, the suppressed evidence hadn’t been located or even suspected to exist. All he had was a vague theory based on the fact that he knew Beckcom had lied about him confessing. Jeff would have needed discovery to learn about some of what the State was hiding, but you only get discovery in Texas state appeals after an evidentiary hearing has been ordered — and the hearing can only be ordered if the trial court has determined that “controverted, previously unresolved factual issues material to the legality of the applicant’s confinement exist”. If that sounds like a catch-22 to you, you are not alone. Maybe now you can see why I stated earlier that this was a foolish ruling. I’m a loser that has been stuck in a concrete oubliette for 17 years. I have zero formal legal training. If I understand the impossible demands the court is imposing, then surely, they do as well. Their stance is also remarkably coldblooded: regarding Jeff’s pro se filings — which actually did make the very sort of allegations the Fifth now claims his lawyer needed to have made — their only response was to say that, “Prible’s pro se filings are irrelevant because they were procedurally improper.” Again, process is more important than outcomes, a specific order of events has more social value than human life. I will explain what I think is going on here shortly, but I think it’s pretty clear that whatever this is, it falls outside the boundaries of the law as we like to think of it in the decent, modern sense. It certainly isn’t in harmony with any conception of moral behavior that I can identify. If a human acted this way rather than an institution, you’d call them a sociopath — and you’d be right to do so.

These positions of the Fifth run directly counter to the SCOTUS’s findings in Banks and Strickler. Indeed, the Fifth seems to have been aiming to establish a new version of Brady, wherein if the State repeatedly attempts to conceal exculpatory material and then lies about it for more than a decade, the appellant will nevertheless be denied relief if he is unable to discover this malfeasance during the first months of his appeal. That’s a pretty direct contradiction to what the Supremes decided in Banks when they wrote:

“Our decisions lend no support to the notion that defendants must scavenge for hints of undisclosed Brady material when the prosecution represents that all such material has been disclosed… A rule declaring ‘prosecutor may hide, defendant must seek’ is not tenable in a system constitutionally bound to afford defendants due process.”

Instead of this putting the issue of “cause” to rest, the Fifth Circuit’s decision skirted it. Indeed, the judges on Jeff’s panel seemed intent on avoiding the actual content of the federal judge’s ruling. On eight separate occasions, the Fifth wriggled out of having to deal with the ugly facts discovered by Jeff’s attorneys by claiming that some later point was irrelevant because Jeff didn’t have the right to bring it up:

- “Because we conclude Prible has not overcome procedural default, we do not reach the latter two points” (which dealt with newly discovered evidence and whether his claims had merit) (Panel op. at 16).

- “And because [Prible] has not shown cause, we need not consider prejudice” (Panel op. at 26).

- “We disagree as to cause and so need not reach precedent” (Panel op. at 27).

- “Therefore, ‘we need not consider whether he would be prejudiced by his inability to raise the alleged Massiah violation at this late date'” (Panel op. at 29, citing Murray, 477 U.S. at 494).

- “We disagree as to prejudice and so need not reach cause” (Panel op. at 30).

- “Because we conclude Prible has not shown prejudice, we assume suppression and express no view on this argument” (Panel op. at 30, footnote 12).

- “Accordingly, Prible has not shown prejudice to excuse the default of his Brady claim. We thus need not consider cause” (Panel op. at 32).

- “Because Prible has failed to show cause and prejudice to overcome his procedural default, we need not decide whether 28 U.S.C. Section 2254(e)(2) barred new evidence nor need we reach the merits of Prible’s claims” (Panel op. at 32).

Forgive me for thinking that reaching the merits of a death-sentenced prisoner who has proven State corruption might just be the point of the entire judicial exercise. If not, what is going on here, behind the curtain? I suspect the answer is limits testing. The Fifth Circuit is the most conservative federal appellate court in the nation. We have a new right-wing supermajority on the Supreme Court, so the 26 judges of the Fifth are the most likely sources for probing just how far the SCOTUS is going to bend legal doctrine to the right. This is not new. For some years now — decades, arguably, on some issues — the Fifth has been chipping away at long-standing norms, everything from abortion rights to anything having to do with the administrative bureaucracy — that poor, much maligned “deep state” that actually makes America a functioning nation. One of the three judges on Jeff’s panel, Trump appointee Stuart Kyle Duncan, is arguably the most radical judge sitting on any circuit court in the nation. He’s a federalist society guy — a believer that the Constitution ought to be read with the original intentions of its writers. If that statement doesn’t trouble you, ask yourself this: In what situation would you prefer to rely on factual evidence from 1776 verses what we know today? If you were diagnosed with esophageal cancer, would you opt for modern scientific treatments, or those available to the Founders? Would you prefer to house your family in a structure built to modern specifications, or those that were current 250 years ago? You know what you would choose. Why on earth would you care what some ignorant mammals thought about anything two and a half centuries ago? Try to keep that in mind, the next time someone tries to sell you on that view, your average fifth grader knows more facts about the world than an entire room of the best thinkers on the planet did at the dawn of our nation. Nevertheless, this sort of thing is what passes for thinking in the Fifth Circuit. Duncan never had to sharpen his constitutional fantasies against the whetstone of reality, because, like many of the Trump appointees, he didn’t spend his years working his way up through the district courts. Instead, he obtained his “expertise” working for the Texas Solicitor General’s office, the lawyers who argue Texas cases in front of the SCOTUS. In other words, Duncan was a politician from the start, one who never even had to pretend he was anything other than a culture warrior. Why would he be any different now?

The entire purpose of the Supreme Court is to resolve differences that arise in the circuit courts. That’s their job. For capital litigants, this is generally not good: we go to the Supremes as a final station on the track that leads to the death house, but few of us have appellate issues that fall into the midst of a current court split. Meaning: the SCOTUS is unlikely to take a long look at us — or, indeed, any look at all. I don’t know what the current statistics are for capital cases granted cert. Years ago, I was told less than four percent, but that always seemed far, far too high to me. Even so, I thought Jeff had a legitimate shot at being amongst this small group, because his case finds itself squarely in the center of not one but two massive court splits. The first deals with the issue I detailed above, whether due diligence must be considered in an analysis of suppression, and whether this qualifies as “cause” to excuse procedural default. The second is a bit more esoteric: a squabble over the “relation-back” issue I mentioned in Day Eight; that whole thing about whether you could have procedural default excused if newly discovered evidence was the same sort as something you previously alleged — the apples and oranges metaphor, if you recall. Judge Ellison found that all of Jeff’s claims shared the same set of operative facts as ones made earlier (apples to apples); the Fifth decided that this somehow meant that they did not need to perform separate cause analyses. In their words: “Prible cannot have it both ways; he cannot rely on relation-back doctrine… to overcome timeliness issues and now argue the claims are so factually distinguishable to rely on separate cause analysis.” But these were separate claims, and each did relate back to separate points alleged in previous filings. The Fifth’s logic would require an appellant to present only a single cause for procedural default, no matter how many actual alleged violations occurred — which may have been the point, as it would give the State an enormous advantage in dismissing cases like Jeff’s. In any case, their ruling here actually seems to contradict their own previous jurisprudence on the subject. Just over a decade ago, the Fifth created some major new precedent in Martinez v. Ryan, in which they had no problem at all in dealing with multiple causes for excusal of procedural default. Whereas the Fifth’s position on suppression runs counter to decisions made in the Second, Third, Fourth, Ninth, Tenth, and DC Circuits, I can’t find a single court that agrees with the Fifth on the relation-back issue. They literally stand alone on this one, for good reasons. (If a lawyer happens to be perusing this site and feels I’m misreading Fed. Rule of Civil Procedure 15; AEDPA, 28 USC Section 2242; or Mayle v. Felix on this point, I’m open to being educated. It sure seems to me that every other court in the nation consistently evaluates relation-back issues as being separate from whether or not an appellant can be excused for procedural default, but maybe I’m missing something. Comment below if you care to.)

These are serious issues, and Jeff had a serious team gathered to address them at the high court; in addition to his normal attorneys in Houston and Austin, he picked up three more from the DC firm Sidley Austin. Their brief to the SCOTUS correctly pointed out that the Fifth Circuit’s ruling was nearly schizophrenic in its attempts to insist that Jeff should have figured out the State was hiding something, even as it acknowledged his “lack of concrete evidence to support his claims”. It was a good brief. Before Kennedy retired, Chief Justice Roberts was well known to step in and side with him and the liberals on issues that might impact negatively on the court’s reputation, not to mention his own legacy. Since Kennedy left — and especially after Ruth Bader Ginsburg passed away — Roberts has had no way to control the five other conservatives. Meaning: had Jeff made it to the SCOTUS four years ago, I think they’d have heard his case. More; I think he’d have won. Instead, on 20 June 2023, 37 months after being told by a district judge that he was going to get a chance at proving his innocence, the Supreme Court denied him cert. Game, set, match. The State wins. In its seminal Brady ruling, the court found that “society wins not only when the guilty are convicted but when criminal trials are fair” (373 US at 87). My first thought when I heard the news was that someone should try to remind them of that on occasion, but of course they know what they are doing. Thus does judicial activism change the nation, one nudge at a time — or in this case, one execution at a time.

I don’t know what is going to happen now. For most capital litigants, a denial at the high court is the end of the road. My own prosecutor waited maybe four nanoseconds before he filed the motion to set my execution date. Jeff’s situation is a little different, because during the years he spent in the federal courts, Harris County experienced something of a political revolution, and all of the relevant officials involved in the criminal justice sphere are now Democrats. Maybe, just maybe, this might give Jeff the chance to use some of the information his team discovered during his federal process on a subsequent state writ, though Texas makes this process very difficult. I happen to think the Fifth Circuit outlined the basis for a potential ineffective assistance of counsel claim against Roland Moore, Jeff’s state habeas attorney. The judges blamed Moore for not investigating the claims Jeff made in his pro se filings, saying it was “incumbent” on him to try to locate Carl Walker. Of course, they then go on to say that attorney “negligence” is not cause for excusing procedural default, “because the attorney is the petitioner’s agent… and the petitioner must bear the risk of attorney error”. There’s that sociopathy I mentioned earlier; you tried to let everyone know your DA was corrupt, but your attorney didn’t believe you, so you have to die. Just exactly like what the Founders would have said, right, your honor? Does this actually make sense to anyone?

So, that’s where we are. Maybe Jeff can convince a state court that exceptional circumstances exist, and they will agree to take another look. Maybe Kim Ogg, current District Attorney in Harris County, isn’t entirely comfortable with what the courts have done here; she, at least, appears to be an actual human being, unlike the previous few holders of her position. Maybe she will allow him the time to file something. Maybe, maybe, maybe, and if I had another one, I could start a farm. Jeff is simply venturing into what is, for me, uncharted territory.

I am confident about one thing, though: Jeff is going to need some kind of public support eventually. His attorneys have seemed to me to be far too media-averse up to now. I think I understand their fears, but the flip side to all of that is that it is entirely possible that had Jeff enjoyed the backing of a few newspapers, the Fifth’s political calculus might have been different. I don’t know how to arrange that for him; if I knew the codeword or secret handshake to the club of prisoners with large support networks, I’d already be inside and not constantly knocking on the glass begging for scraps. Prisoners in Texas were given Securus tablets in April, so we can receive emails and phone calls. If you feel you have something to add here, reach out to Jeff, help him coordinate his next steps. Beyond that, share his story on social media. If you are not certain that I have told Jeff’s story straight, you can easily read his court filings at https://pacer.uscourts.gov/. I’ve left a few details out here and there, in the interests of keeping a complicated story streamlined, but none of those details help the State’s case in any way — indeed, most of them were merely additional examples of prosecutorial malfeasance. I figured you’d seen enough of that by a certain point.

I’m going to have to write a tenth chapter to this series. Help make its ending better than this one had to be.

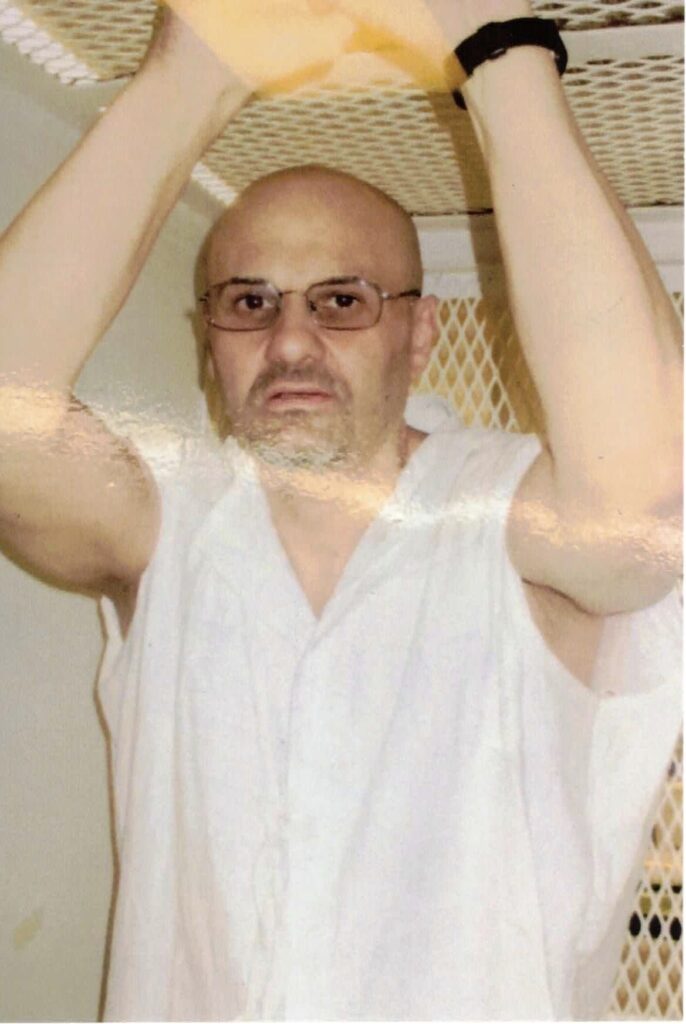

Ronald Jeffrey Prible 999433

P.O. Box 660400

Dallas, TX 75266-0400

No Comments