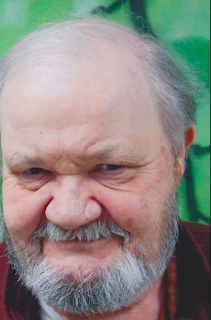

By Burl N. Corbett

To read Chapter Two click here

An Uptown Gig

Sean’s mental alarm clock rang at five. He’d never worn a watch, even before he’d come to the Village in 1966 to be a writer and had luckily fallen in with the last of the beatniks rather than into the clutches of the burgeoning hippie tribe, praise the lord and pass the number! The weekend scouts of the hippie tribe-–the bridge and tunnel teeny-boppers–would soon be followed en masse by the thundering herd itself once the high schools and colleges closed for the summer. But for now, before the deluge, there were more piss-stained winos on Bleecker Street than tie-dyed flower children. On his way back to his loft, Sean passed three of them huddled unconscious on his old sofa, brain-dead to the world.

He entered his building at 6 Bleecker and sprinted up the five flights of dusty stairs to find his door unlocked, a definite no-no in a city-that-never-sleeps full of take-off artists-who-never-sleep. Even the presence of Mark, crashed on his platform bed with his chick Annette, was a poor deterrent: Just two weeks ago a burglar had stolen Sean’s eyeglasses from his mattress-side crate while he slept. Nothing else was stolen, an eloquent if sad testimonial to his poverty and the efficiency of his habit of hiding his wallet underneath the mattress when he slept.

“Mark!” he called, changing into a pair of worn, oil-stained Wranglers, a reminder of the not-so-distant days he’d spent working on cars in his neighbor’s barn. “Mark! You up, man?”

A shadow moved on the ceiling and Mark groaned. Then, nothing.

“I’m going to Minuteman today, I’m broke.” He only had six Pall Malls left, so he “borrowed” four Marlboros from Mark’s pack. He could tear off the filters later. “Feel like coming along?”

Mark cursed loudly and pulled the sheet over his head. Sleeping on a street-salvaged mattress and living the beatnik life for a summer or two was a cool listing on his hip resume, but doing without a sheet or pillow was a cat of an entirely different color. “Are you fucking insane?” he shouted. “Fuck no, I’m not going! Just hearing about it bums me out!”

Locking the door behind him, Sean thundered down the steps. He turned right on the Bowery and walked the bum-haunted blocks to Houston, watching alertly for fresh pools of urine and stray turds: the spoor of the wild wino, Urbana derelictus. At Houston, he crossed against the light, walked a couple blocks, and entered the waiting room of Minuteman.

The bald dispatcher glanced up and smiled. Sean signed the register and sat down in one of the dozen folding chairs. Four men were already there, smoking and sipping containers of coffee. They weren’t yet full-bore winos, but they bore the stigmata of the chosen: trembling hands, undernourished lanky bodies, and a sour body odor that would worsen as they worked up a sweat. None looked at Sean or the others; they kept their eyes on the floor. The worst part of their day was when they faced themselves in the mirror. They sat inert and silent as more men sidled in and took seats. One man began to gag, then leapt to his feet, ran outside, and vomited in the gutter. He did not return. A few pigeons, pecking and nodding and cooing, examined his offering with cocked heads. Spurning the hot meal, they waddled out of sight. The man next to Sean stared after the departed birds with a haunted expression. When the dispatcher’s phone rang loudly, he twitched as if stung.

The dispatcher grunted, mumbled a few words, and scribbled on a pad. He hung up the phone and surveyed the rows of men. No one, except Sean, met his eye.

“You two over there,” he decided, pointing to his choices. “Yeah, you two on the end. Come here.”

The men, both black, came over and stood quietly in front of the desk. They were given a slip of paper with the job address and the boss’s name on it and a dollar bill for carfare. Although they were heading to the same job, once they were outside they walked twenty feet apart, as if mortal enemies.

The phone rang steadily now, and one by one the men were called up to the desk and sent away. As Sean patiently waited, latecomers straggled in. It was always like this; he was often sent out last. At first, he thought it was because of his hair–the dispatcher probably considered him a beatnik, or worse: a no-good hippie/ draft dodger/Commie/dope addict/faggot. But he was always chosen, and usually for the easier jobs. Not for him, the ball-breaking jobs without freight elevators, where the rubble and debris had to be lugged up basement stairs in shouldered baskets. He thought he was just lucky, until the day he noticed something in the man’s voice, an undefinable vibe he picked up. Suddenly the meaningful glances, the smiles, the unctuous demeanour, the easy jobs all added up, and Sean’s twenty-year-old naiveté took another blow–the dispatcher was hot for his body!

When he told Sam his conclusion, Sam thought it was funny. “Far out, man! What a gas!”

When Sean failed to see the humor in it, Sam explained. “That’s great, man! String him along, keep him thinking he has a chance with you. Keep him guessing.”

“String him along? I want to do the opposite–disillusion him!”

“No, no, fucking NO! What do you want him to do? Send you out on all the shitty jobs because you broke his heart? Use your head. Think like a hustler! If he tries to get physical, then disillusion him. In the meantime, smile at him, rap with him, let him think he has a chance, dig? Con him, man, con him!”

That had been over a month ago, and so far the easy jobs kept coming, and the gay dispatcher seemed content to just make with the eyes. He’s fucking scared! Sean realized. He isn’t just in the closet; he’s hiding under a pile of quilts in its corner! So, Sean played his role, and the man his, and everything worked out just fine. Since Sean only worked one or two days a week, the charade was easy to sustain. His absences not only made the man’s heart grow fonder, but enabled Sean to avoid an ugly confrontation, which steadier employment might have provoked. An old white trash Southerner had once told him that “work is for a mule, and he’ll turn his ass to it,” and Sean now saw his point.

All the men had been sent out, except Sean and a black man in his early fifties, “Both of you, come here,” the dispatcher called. He slid the address to the black man, who glanced at it and put it back on the desk. Sean stood quietly and said nothing. The three of them appeared to be engaged in an obscure ritual in order to affect an undetermined outcome for no particular purpose.

“It’s the address of the Empire State Building,” the dispatcher said, He looked at Sean, then the other man. Neither seemed impressed.

“I been there before,” said the other. “You got our carfare? We best be gettin’ along now.”

They were each given a one. When they got outside, they introduced themselves.

“I’m Sean.” He extended his hand.

“Gardiner.” He accepted Sean’s hand and they shook. “That goddamn fool acts like we owe him a tip or sumtin’. Big fuckin’ deal–the Em-pire State Build-in’, like we was tourists. Plaster’s plaster, whether it be on the first floor or the fuckin’ ninetieth. It’s still heavy, still dusty, still backbreakin’ work for peanuts.” He spit on the sidewalk for emphasis.

On the subway ride uptown, Gardiner rapped without pause, bitching and moaning, wishing he were heading home instead of starting out. Sean listened half-heartedly, tossing in a “Right on!” or a “Fucking aye!” at lulls in the tirade. By the time they reached their stop, Gardiner seemed to have talked himself out. A small dump truck was parked at the job in a “No Stopping. No Loading” zone. Its driver sat on the running board sipping a coffee and two tall, muscular black men leaned against a pair of steel buggies bristling with shovels, brooms, and eight-pound sledge hammers. The three men greeted Gardiner and Sean with short nods.

“Each of you grab one of these carts and follow me,” one of the demolition men ordered. The truck driver opened a Daily News and said nothing. They pushed the buggies through the chocked-open door and rattled through the lobby to the freight elevator. There was room for only one buggy at a time, so it took two trips before they were all on the thirty-sixth floor. They pushed the carts into a large, empty office, where the demolition men were going to knock down a wall to create a bigger space. Without further ado, they began to hammer down the plastered terra cotta wall, grunting with each swing. Soon the air thickened with dust as Sean and Gardiner began shovelling the debris into a cart. After the first one was full, Sean pushed it to the elevator, and Gardiner began to fill the second.

As Sean and the cart emerged from the building, he overheard a mounted policeman informing the driver he would have to move his truck. While the cop and driver jawed back and forth, waving their arms, the horse whinnied and switched its tail. One or two passers-by looked as if they might attempt to pet it, but they had second thoughts and walked on, making odd kissing sounds. Meanwhile, the driver had maneuvered the cop between the horse and the truck and pressed a twenty into his hand, still making a show of complaining. After more theater and loud warnings, the cop remounted and clopped away. The driver sat back down on the running board, lit a cigarette, and winked at Sean.

“He ain’t no Douglas MacArthur — he won’t return. Dump the cart and start shovelling.” He picked up his paper and resumed reading.

The morning passed quickly. Sean and Gardiner spoke very little as they shuttled the buggies up and down the elevator. At nine-thirty, the nameless John Henrys lay down their hammers for a coffee break and Sean asked them where the rest room was. Gardiner had worked there before and offered to show him.

“I gotta piss, too, man. C’mon, we gotta go to the next floor.”

“Don’t they have shitters on this floor?” Sean asked, looking around the room.

“Got the water turned off,” Gardiner said. “Can’t use ’em.”

One of the hammer men gave Gardiner a contemptuous sneer. The other caught Sean’s eye, cautioning him with a funny look to “Take care, now.”

Sean followed Gardiner to the elevator. “We better use the one for the maintenance workers, seein’ that we so dirty,” Gardiner explained.

“I’d like to come back when I’m not working and go to the top,” Sean said. “But I guess it would cost a few bucks, huh?”

“Yas, that it do, yas, yas, yas-—just like everythin’ in this fuckin’ town.”

“How much do those cats swinging the hammers get?” Sean asked, as they got off the elevator.

“Sheet! Those cats get damn near nine bucks an hour, but, man, they sure as hell earn it!”

It seemed a fortune to Sean. He got about a buck fifty-five an hour, and after the carfare and the various taxes were subtracted, plus the bottle of Rheingold he had to buy to get his check cashed, he was lucky to clear nine bucks for a day’s work. But then he could live on a couple of bucks a day, including cigarettes and the occasional quart of Ballantine Ale. His rent was only sixty-five a month and Mark paid half of that. They were paid two months ahead, and after that Sean didn’t much care. It was common knowledge that it took at least a year to evict deadbeat tenants in New York City. To a pair of young hipsters, that was an eternity.

The bathroom was at the end of the corridor, and contained a grimy toilet and a deep janitor sink. The shelves of the small room were stacked with cleaning supplies and light bulbs. An old easy chair was in the corner. It was a perfect hideaway in which to kill time. An overflowing ashtray by the chair proved that it was well-used.

“Use the hopper, man. I’ll piss in the sink,” said Gardiner, bellying up to the porcelain trough.

Sean didn’t mind; he had never been what was called “piss shy.” He and his boyhood friends had often urinated in groups, writing their initials in the snow, or striving for the longest distance. He had finished and was zipping up when Gardiner turned around, his long, semi-hard cock in his hand.

“I always did have a big pecker,” he mused. “Maybe you ain’t ever seen one this big, but if you wanna touch it, I don’t mind.” He leaned back against the sink and grinned. “Don’t be scared, man, show me yours.”

“Fuck you, you son of a bitch!” Sean replied, outraged. “You better stay away from me, man! I’m not into that scene!” He walked out, leaving Gardiner standing cock in hand. He took the stairs down to the job, and when he came in the room alone, the hammer men looked up.

“Did that cocksucker try to hit on ya?” one asked.

“Yeah. I told him to back the fuck off,” Sean replied, wondering how he knew.

“He tries anymore of that shit, smack him in the fuckin’ face with your shovel,” the other man advised. “We’ll see that you don’t get jammed up.”

When Gardiner slunk in a few minutes later, no one mentioned the incident and they resumed work as before. Sean and Gardiner didn’t speak to each other, but then they hadn’t spoken much before. When Sean trundled down the next cart load, the driver climbed up on the thin ledge around the truck bed and checked the height of the mounting debris. Right before lunchtime, he told Sean, “Tell Jim and Hap that if they load much more, I’ll have to bill them for a double-load.”

Upstairs, he relayed the message to the no-longer-anonymous demolition men. They paused and looked at the remaining wall, then at the debris on the floor. Hap began beating on the wall, and Jim spit on the gypsum-white floor and coughed. He spat again, and then told Sean, “Tell him to figure on a double-load. Tell him we’ll be done by two, maybe two-thirty.” He pulled up his flimsy face mask and hefted his sledge. Sean returned to shovelling.

At noon, Hap and Jim opened their lunch kettles; Gardiner and the driver went to a corner deli. Sean sat on the curbside running board and watched the passers-by. He recalled sitting in his father’s ‘51 Chevy on the main street of Reading, waiting for his mother, while his father passed the time by commenting upon the idiosyncrasies and what he perceived as character flaws of the pedestrians. Eight-year-old Sean had realized with a start that all those weird-looking people had been going by him all life, unnoticed. With a frisson of wonder, he realized that these nameless people, these funny-looking strangers, doubtlessly considered him as much of a curiosity as he did them. Now, only a little more than ten years later, he was in the largest city in America, if not the world, and not much had changed; what little difference was quantitative, not qualitative. He rested in the shade, smoking and enjoying the passing cavalcade of humanity.

Sean liked to work uptown. His hair wasn’t long enough yet to offend the prevailing standards and except for his moustache he was clean-shaven. Aside from his genuine Pakistani water buffalo sandals (with the big toe loop) that he wore even at work, he wasn’t particularly outrageous. Beatle-length hair had won acceptance, and the truly offensive wildman hair and caveman beards were relatively uncommon, even in the two Villages. By autumn of 1967, however, a running joke was that hippies needed a passport to go north of Fourteenth Street. For now, Sean blended with the masses and could wander the glittery/spacious/awe-inspiring/glorious/lovely/noisy/spectacular/stone/glass/steel/aluminium/concrete canyons of mid–Manhattan, knowing in his heart that, while it was a nice place for tourists to visit, it wasn’t too shabby a place for downtown hipsters, either.

New York City was a passion that had possessed him early. His father, a great reader, had brought home a paperback copy of Henry Miller’s Tropic of Cancer shortly after it had been bravely published in 1961. Although he professed disdain for its “vulgarities” and “shock for shock’s sake,” and hid it (not very successfully) in his wife’s sewing cabinet, he nevertheless bought Tropic of Capricorn the next year. Sean devoured both of them, thrilled by the tales of pre-Depression Brooklyn, Greenwich Village, and, finally, Paris. About the same time, Sean got into folk music and learned to play guitar. By the time Dylan went electric, Sean’s mind was already on the train to Grand Central Station, although it took another year for his body to follow.

His senior class trip in the spring of 1965 to the World’s Fair in Queens provided the impetus to leave Pennsylvania. Sean’s first glimpse of the New York City skyline from the cliffs of New Jersey was to him comparable to Balboa’s first glimpse of the Pacific Ocean from atop Mt. Darius, or Jim Bridger seeing the snowy glint of the Rockies the first morning of the rest of his life from the barren plains of Colorado. As soon as Sean got off the bus he left his classmates and wandered about alone, debating whether to catch the subway to Astor Place and leave everything behind. But he hadn’t yet the nerve, and instead at the end of the day found an amenable beer stand where he caught his first beer buzz while waiting for the bus back home. Now here he was, two years later, working in the tallest building in the world, in one of the largest cities in the world, for the cheapest son-of-a-bitching hiring hall in Manhattan. And he loved every goddamn, go-to-hell minute of it!

The driver returned at 12:30; Gardiner fifteen minutes later with a pint bottle of muscatel in a paper bag and another in his belly, mumbling obscurely, his breath a forty proof blast.

“‘Nother hour, hour inna half, we be finish,” he announced to no one in particular, hiding the pint bottle in the cleavage of the truck’s dual rear wheels. The driver mocked him in a high, whining voice, “”Nother hour, hour inna half you be layin’ in the fuckin’ gutter. You best get your ticket punched and take your scrawny black ass back home. These uptown cops don’t like you downtown bums fuckin’ up the scenery. It ain’t good for the tourist bizness.” He climbed into the cab and hunted on the radio for the afternoon ball game.

Gardiner filled one more cart, then told Hap he was feeling poorly and was going home. Hap put down his sledge, took Gardiner’s time card, and checked his watch. It read 1:15. He wrote down six hours and handed it back.

Gardiner couldn’t believe it. “Sheet, man! What’s up with this goddamn static? Why ain’t you put down eight? What the fuck kinda brother is you, anyway?” He weaved unsteadily, leaning on the buggy, his black skin plaster-white and his anger wine-red. His sweat and wine-funk fouled the air.

Hap picked up his hammer and lifted it menacingly. “Y’all get your skinny, faggot, wino ass downtown now, before I send you down the elevator with the rest of the trash! And you tell that fairy dispatcher that if he ever sends your worthless ass to my job again, I’ll kick both your goddamn asses!” Gardiner made to speak, thought better of it, and without a glance at Sean, staggered out the door and was gone.

The rest of the dividing wall was soon down, and Jim and Hap helped Sean clean it up. “Don’t say a word about us helpin’ you,” Jim warned. “We don’t want no union trouble, understan’?”

“Yeah,” Hap added, “and if I was you, I’d find another shape-up joint to work outta. One that ain’t run by a damn homo.”

“Better yet,” said Jim, pushing the last cart onto the elevator, “find a real job. This shit is for day-atta-time bums with no future.”

After shovelling the last of the debris on the truck, they stored the carts in a basement utility room. Hap gave Sean a full eight hours, then squeezed into the truck cab with Jim and the driver. As the truck eased into traffic, the empty wine bottle Gardiner had drained and left for spite exploded, blowing out both tires with a deafening blast. Sean was a half block from the subway entrance when a different mounted policeman galloped by towards the crippled truck that was blocking one lane of rush hour traffic. He wondered if another twenty would be sufficient to the occasion, but guessed not.

|

| Burl N. Corbett HZ6518 SCI Albion 10475 Route 18 Albion, PA 16475-0002 |

Born 6/9/47 in Reading, PA. Raised on a 123-acre sheep farm only three crow miles from John Updike´s famous sandstone farmhouse of “Pigeon Feathers,” The Centaur, and Of the Farm. Graduated from Daniel Boone High School in 1965. Ran away to Greenwich Village to become a beatnik in 1966 with only a Martin guitar and the clothes on my back. Lived among the counterculture for 3 years, returning disillusioned to PA for good in 1968. Worked on a mink farm; poured steel in a foundry; chased the sun as a cross-country pipeliner; drove the big rigs, baby!; picked tomatoes with migrant workers; tended bar on the old skid row Bowery; worked as a reporter, columnist, and photographer for two Southeastern Pennsylvania newspapers; drove beer truck (hic!); was a “HEY, CULLIGAN MAN!”; learned how to plaster, stucco, and lay stone; published both fiction and nonfiction in several nationally distributed magazines and literary quarterlies; got married and raised four children; got divorced and fell into the bottle; and came to prison at the age of 60 with no previous criminal offenses other than a 25 year-old DUI. The “crime”? Self-defense in my own house without financial means to hire a decent lawyer. Since becoming the “guest” of the state in 2007, I have won five PEN Prison Writing Awards (two first and three honorable mentions); the first and only prize of $500 in the 2013 Eaton Literary Agency short fiction contest; written a children/young adult book, Coon Tales; a novel of the 1967 “Summer of Love,” Dreaming of Oxen; a magic realism novel, A Redneck Ragnorak, and many short stories and memoirs. My first novel, A Haven from Violence, and Coon Tales, is available at Xlibris.com or Amazon.com.

1 Comment

piscator

February 24, 2018 at 2:44 pmMr. Corbett,

This is a wonderful, well-crafted, story!

While I'm a little closer to the hippie side of the generation, your brilliant depictions of Manhattan, in those years, brought back memories. I attended the '65 World's Fair when I was only seven, but I can still recall scenes that were, to my young mind, magical.

Thanks for enlivening my morning. I wish you all the best.

Sincerely, piscator