Quickly, now: when I say the word “prison”, what visual imagery immediately pops into mind? You probably thought of some combination of long rows of grimy bars à la Shawshank Redemption, tatted miscreants plotting or punching on each other, chain-gangs marching in cadence, hoes over their shoulders — things of this nature. Many of you probably also crafted depictions of tall fences, perhaps rimmed with endless loops of glinting razor wire, occasionally punctuated with forebodingly grim, gray gun towers. Nothing visually defines the site of American-style incarceration quite like the fence. It is the boundary between two vastly different worlds, each with completely distinct moral codes, norms, and mores, much likely a national border, only the cultural differential gradient is far steeper. The primary purpose of the barricade is obvious: it is meant to keep we feckless wastoids, with all of our obvious flaws and moral dyslexias, away from you. That this barrier has a secondary function is not as often remarked upon, though every prisoner comes to learn this well and usually rather quickly: the fence also prevents the flow of information from traveling outward. This has always been intentional. Many of the first theorists of the modern penitentiary believed that the creation of nightmarish, Gothic tales based on information leaking out from the prisons would have a didactic, social value in deterring crime, but they were careful in how much escaped and what this information consisted of. Throughout all of the various cycles of reform and regression that have marked this two-century experiment, the walls have remained, patiently fulfilling this function as a highly selective impermeable membrane. It is one of the few things that have never really changed.

So when a prison system voluntarily peels back the looped razor wire curtain, you can be sure that something interesting is happening. Heidegger believed that boundary lines described not the ending of something but rather a “presencing” — a beginning — of something new. While I hesitate to quote a man whose political choices were so ghastly, in this case I think he was on to something. During my seventeen-plus years in isolation, I have rarely seen the administration permit any sort of freeworld volunteer access to an admin-seg wing. Across four units, the reality has remained the same: occasionally, churchy volunteers are permitted to hold revivals in general population, but they are seldom allowed in the Hole. On the uber-rare occasions when this does happen, the visits are perfunctory to the point of pointlessness. On only one occasion have photographs of an admin-seg wing ever been made public in Texas. I wrote an essay about this collection fifteen years ago, and it remains one of the most viewed works on this site. Useful, perhaps, but what I really wanted was video. I figured short of an investigative journalist smuggling a camera into the facility à la Shane Bauer, that was a pipe dream. No way the Texas Department of Criminal Justice (TDCJ) would ever permit such a thing, right?

Enter with me into the agency’s current bout of schizophrenia. I am living — if that is in fact the right word for what I am currently doing — during an era where the system is being pulled in opposite directions by two very powerful impulses. One, held by the traditional security apparatus, still largely remains in control. This drive is neurotically focused on prohibiting all change: security is defined as the art of making nothing happen. The other is being pushed by conservative Christian groups that seem to have cultivated some powerful friends in Austin of late, and is oriented towards pushing an agenda of Christian education — so long as this is defined as Protestant, literalist, neo-Calvinist, and millenarian; more liberal or modern iterations don’t seem to be very welcome, and neveryoumind other faiths or (gasp) sciencey types. These political connections have manifested in various ways, none more obvious than the numbers of ministers the TDCJ is allowing in through the gates. The actual value these people bring is highly questionable at best, but that is a whole other subject. The point is that in the tug of war over the keys to the penitentiary, the Christians are actually winning on occasion. Earlier this year, one of these wins included the introduction of a video camera into 12-Building at the McConnell Unit in Beeville — my home. You can find this footage here on the YouTube channel of Worthy People, the group of ministers who visited my prison. My thanks to anyone involved in posting this, whatever I may think about your theological views. Below, I will walk you through the relevant scenes and describe exactly what you are witnessing. I am able to do so because the same video was also posted on Pando, an app on our tablets consisting of Christian sermons.

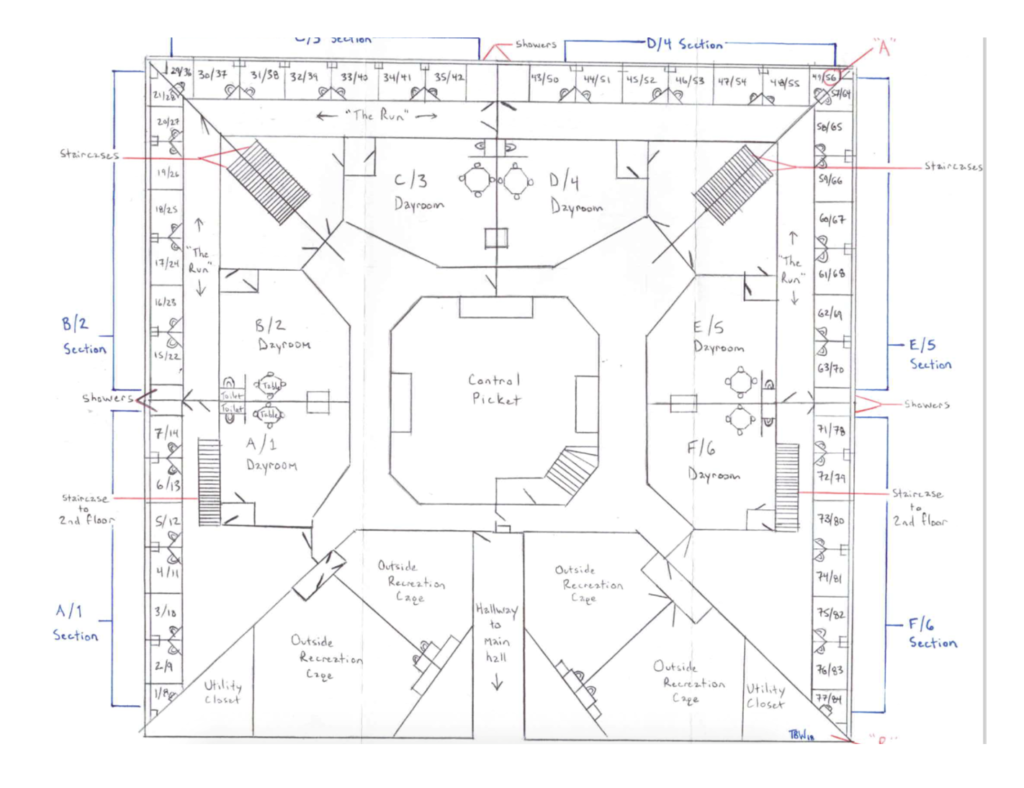

The entire video is quite long, right at fifty minutes. Fortunately, the admin-seg portion only consists of a bit more than five minutes; this section begins at 41:02, though if you care to see some of the scenes from population at several different units, you can start viewing at around minute 33. Don’t hesitate to pause and rewind the video as you read my descriptions; I really want you to get a good look at what you are seeing, and one pass is seldom enough for close analysis. The first few seconds after 41:02 show two field ministers at the door to C-Pod, 12-Building. Each seg building in the 2250-style prisons consists of six of these pods, A through F. Each contains 84 cells divided into six sections and is consistent with the following diagram (though B-, D-, and F-Pods are on the opposite side of the main hallway, and are a sort of mirror image of A-, C-, and E-Pods as to which side the main crossover door is located).

As the video proceeds, you see the older field minister (Phillip) turn to the left through central crossover (41:12). CA, CB, and CC sections are through this door, what we prisoners call the “low” side of C-Pod. These are the 42 cells designated for the Faith Based section, what I have referred to as the “God Pod” in the past. If the camera had turned to the right instead of the left, you would have seen CD, CE, and CF sections. At 41:10, you can see an officer standing at a window. The other side of this structure is the guard picket, the central panopticon for the pod.

At 41:16, you get a straight shot of CA section, which contains cells 1 through 14. In front of these cells is CA section’s dayroom. Each set of fourteen cells has one of these spaces. You will get a better view of the inside of one of these cages shortly, but for now you may notice the new television system installed in April 2023. The metal plate with “PREA” painted on it was welded into place a few years ago. It is basically a privacy shield for the toilet and was made from a set of discarded highway signs. I’m still not entirely clear on what this barrier has to do with the Prison Rape Elimination Act, since the plate only shields a person using the restroom from the guard in the picket, but, hey, there’s really nothing more distinctly Texan than taking money from the Federal Government earmarked for one thing and then using it to plug up all of the holes in your budget left behind after the most recent unnecessary corporate tax breaks — so long as you can score political points amongst the yahoos by simultaneously bitching about federal overreach, of course. Anyways, to the left you get a quick view of the two outside recreation cages, which, due to the drastic understaffing issues plaguing the system since Covid, have become terra incognito to us for a while. We last had a chance to see the sun on 16 February.

At 41:26, the camera shifts 90 degrees to the right. The second day room on the left is CB, with CC directly ahead. I lived in CB section, 22-Cell. This is the cell furthest to the left on the second floor. In fact, starting at 41:37 up until around 41:39, as the camera takes in the view, you can see my silhouette in the right-hand window of my door; I had come to see what the field ministers were yelling about. You can see me start to walk away as I figure it out.

From 41:48 to around the 44-minute mark, the camera spends some time in CC section, or cells 29 through 42. At 41:53, you get a good view of the staircase. Just above this you can see a gray box attached to the wall with a pair of WiFi antennas protruding. This is the anti-cell phone system for the section. At 41:56, you get a good view of several cells. These door’s features consist of two, narrow vertical windows, underneath which is the locked tray slot. The smaller rectangular doors located between each cell is the access panel to the pipe chase. On the ceiling, you can see several sets of exposed metal conduits. Some of these hold the wires that connect the five cameras in each section to the security servers, while others lead to white boxes; these are the WiFi emitters for the tablet system.

Above some of the doors you may have noticed little colored squares with certain letters. These are security precaution designators, the equivalent of merit badges to those of us living in the land of the Machiavellians. The more you have, the bigger a badass you are deemed to be by the administration. There is a sort of hierarchy to these tags. “SH” is the most common, technically signifying a propensity for “self-harm”. In reality, the wardens hand this tag out to anyone who has either a long sentence or who regularly causes problems of a minor nature. “CB” is the contraband designator, meaning you’ve been busted with dope or phones. “SR” means you have proven capable of slipping your cuffs or defeating your door’s locking mechanism; “SA” means you have occasionally engaged in fisticuffs with the staff. The most significant is the High-Profile tag, which, alas, I have been carrying about like Sisyphus’s damned stone since my commutation in 2018.

Proving once again that in the TDCJ the squeaky wheel gets all the grease, at 42:55, the ministers stop to get some audio from the champion cell warrior on C-Pod, i.e., the biggest shit talker. He apparently sold the Fire and Brimstone Brigade the idea of his immediate conversion to Christianity, a point which I suspect his neighbors would have found to be quite surprising and perhaps less than convincing, considering his subsequent daily behavior. That the ministers gobbled it up is not surprising. I mean, when you spend a sum total of less than ten minutes in an environment, you are never seeing things for how they really are; rather, you are seeing them for how you are, and in the narrative of these folks, a mere few words is enough to drastically change the trajectory of someone’s life. And that’s really at the core of my bone to pick with most of these visits. They’re really just a kind of low-rent, amateur dramatics society presentation. The administration performs a Potemkin Village spruce-up and comes through wiping away the usual strata of grime. They only give access to the best-behaved inmates, and even then, they require that most of the audio be covered up with cheesy music — God forbid you, the public, actually hear what was being shouted for most of the duration of the visit. The ministers got some nice video for their financial backers and, of course, they now get to bask in the glow that comes from bringing the truth and the light to the heathens. But what actually changed? Nothing. Absolutely nothing. None of these people asked questions about how we were living or why. None of them seemed morally troubled or promised to write their congressional representatives. If anything positive is to come out of this entire business it will have to come from you, deciding that you don’t like the images that you are seeing here and using this decision to vote in candidates supportive of prison reform. That’s it. Everything else is just wasted electrons darting about inside that brain of yours. No God is going to fix this. Only you can.

At 44:06, the camera returns to my section. You will see the dayroom cage to the left as the chaplain and the volunteer walk towards the cells on One-Row. 15-Cell happens to be my buddy Brandon Gilleland; to the left of Brandon’s cell is the shower for the ground floor. 16-Cell is my friend RayRay.

At 45:11, you will get a good view of what the inside of the dayroom cages look like. According to policy, we are supposed to have access to these dayrooms once a day for one hour; you will constantly come across references to the men in solitary suffering through “23 and 1”, implying that that one hour outside of the cells is common or guaranteed. This is false: it has been false for years. In 2023, we were denied recreation 297 days out of the year. That’s 81.4% of the time, if that helps you place this in perspective. We are, in all the ways that matter, permanently locked down. This was clearly the case on the day of this footage: note, the distinct lack of inmates in the dayrooms. When we are allowed out, we do so alone in that dayroom cage. As you can see, it contains a table, a chin-up bar, a toilet, and now — thankfully — a television. You can talk to the guys in the cells, if you’ve a mind to. That’s it. That is the extent of your social world. There is nowhere else to go. That short walk to the dayroom is essentially the compass of your world. You will not move further away until you leave. Those few meters are your entire existence.

Try to imagine, if you can, the ways in which this type of life would limit you. I’m not talking about your options, exactly. I’m talking about the ways your very essence would be diminished. We are all of us socially created. Who you are — your beliefs, your moral code, your sense of purpose and meaning in the world, your personality, and likes and dislikes — all are created in whole or part via your interactions with the greater world around you. Can you fathom the ways that the truncated existence I have shown you would change who you are down to the most basic level of your being?

An example from my own life, to illustrate the point: on 12 March, Snow Man, one of the prisoners here on the God Pod, died. The initial story told to us was that he had overdosed, but the nurses quickly corrected that version of the story to say, no, he simply asphyxiated on his vomit after getting high — as if this were somehow an improvement. I had known Snow Man since my time at the Michael Unit, in 2018. He was generally well-liked with a (maybe somewhat feigned or at least intentionally exaggerated) big dumb brute sense of humor, the bull in the proverbial China shop, but one whose destructive tendencies were aleatory and who kind of made you laugh even in the midst of his more entropic moments. Some of my neighbors mourned him, and this didn’t seem like mere performance art, something you can never completely discount when living in the Faith Based section, where virtue so often amounts to little better than a form of one-upmanship. There was a bit of handwringing amongst the Christians about whether he was genuinely “saved” or not, and what his continual drug use and occasional references to Valhalla implied about the validity of his conversion. For me, the news arrived with a sense of a key slotting perfectly into a well-oiled lock. Of course Snow Man died from bad dope. We had all been hearing for months about the overdoses in the building, the nightly trips to the local hospital, how much of the K2 being sold was really fentanyl or roach spray or embalming fluid. Snow Man was a magnet for improbable unpleasantnesses, from the time he fell asleep and allowed his souped-up hot-pot to catch on fire, causing the commissary lady to complain about the smoke, thus delaying the delivery of our loot for more than a week, to the occasion when he got drunk and passed out slumped over the dayroom table on the same day the regional director decided to pop by for a snap audit. If you’d had told me that someone on my pod had died from such-and-such circumstances, I’d have immediately thought of Snow Man, because that’s the way this world works.

I don’t like any part of what I felt when I’d heard he’d died, that sense of the inevitable universe spinning along on its inevitable cycles, everything in its right place. It doesn’t help a bit that I know exactly how I got this way. The State murdered 161 men during my eleven years on death row. Especially in those first few years, it felt like they were taking someone away every few weeks and they seldom came back. During the past six years since my commutation, my life has been defined by churn: people are constantly getting shipped to new units, or they are going home, or, occasionally, they die. Someone in my environment will pass away between the time I mail this essay out and when it is published later this year — that’s not prophecy, that’s statistics. (Late note: Two, in fact: my friend Big Louis Perez died in June, and my neighbor Little E passed away from complications of pneumonia and untreated leukemia.) People, in other words, whatever their qualities and whatever else they may represent, are first and foremost temporary. They come, they may mean a great deal to me for a time, but eventually they always vanish. That has become the function of people for me. There is always a countdown running in the back of my head after I’ve met someone now. (I realize, too, that there is an antecedent to this view: due to my frequent transfers to various schools as a child, my entire social world was similarly ephemeral during those formative years. Who we are is but a series of overlapping echoes, alas.)

Of course I have rationalized all of this, being prone to such things. I am attracted to the Buddhists when they speak of the suffering that comes from clinging to relationships, to people. I nod when I read in Epictetus or Lucius Annaeus Seneca about not allowing any loss to impact my balance, my equanimity. There is a resonance within me that seems to harmonize with truth when I think about hormesis or its inverse, the absence of challenges, and how this can degrade you. I have memorized quotes from Cato the Censor (comfort is the path to ruin) and Ovid (ingenium mala saepe movent) to buttress me during these frequent moments of loss. All of this makes perfect sense to me, based on an overwhelming abundance of evidence. “That which does not kill me makes me stronger” is not without its attractions — and yet, I cannot deny that these experiences have made me calloused, because, surely, Snow Man was alive and he had dreams and a family and friends that loved him and I miss him and his passing was worthy of tears but I cannot summon them and I doubt I have been able to for years. Whatever good might be said about my attempts to wrangle my emotions into some form of obedience and connect with my inner Vulcan, it cannot be said to be a good thing that I feel my empathic motor once had a higher gear or two that seem to have shattered and fallen off somewhere along this rough path I have traveled. That which does not kill me, makes me colder — apparently.

I know that I am not alone in feeling something like this amongst my peers. There was quite a bit of anger directed at Snow Man from the lifer crowd, which is quite a bit larger than I think the average citizen is aware of. Most of us will never get a chance to go home. No matter how we change or grow, no matter how many good decisions we make daily in the wake of one bad one, society has permanently exiled us to a realm which makes a bad jest of any conception of human dignity or worth. Snow Man, however, was parole eligible. He could have gone home years ago, if he’d been committed to making the right kinds of behavioral changes. To throw away the priceless gift of freedom in pursuit of a cheap high was perceived as a kind of insult to some of my peers. I won’t say I felt this way exactly, but you can no doubt perceive some of my own frustrations with the man bleeding through. Some nasty things were said, about stupidity having a built-in solution. None of that is any good, either. What are we all missing? Can we repair these parts of us that living in this hell have sandblasted away? Or are we forever stunted?

Thoughts such as these have been much on my mind of late, for good reason. After seventeen years surviving in solitary confinement, it looks like my time in the Hole is drawing to a close. There is kind of a story here, one that the writer in me is itching to tell in its entirety. The human being that has to live this life sentence, however, has long understood that my writerly identity has cost me a great deal over the years, in the form of an enormous amount of unwanted attention from the administration. And while I have been held in seg for political reasons surrounding my commutation, the fact that I regularly poke the bear with my pencil has no doubt been a factor. Authoritarians hate fact-gatherers more than any other kind of pest. So, in short, I am going to tell my inner journalist to sit down and be quiet and choose my words very carefully. Maybe, one day, I will be free to be more informative. Very well: for some time, I have been working with staff attorneys at Rights Behind Bars, a legal advocacy group out of Washington DC; such is the wasteland of prisoners’ civil rights in Texas that I had to roam far afield in order to find anyone interested or capable of caring that the government had placed someone in indefinite solitary over a voluntary commutation. As a result of this collaboration, I was able to meet with Bryan Collier, the executive director of the TDCJ, in early February. This interview lasted well over an hour and was actually fairly pleasant. Although Mr. Collier asked me a lot of questions, most orbited a single point: would I embarrass Governor Greg Abbott if I were to be released from the Hole? They were, I suppose, well within their rights to wonder about this, as the last guy who received voluntary clemency before me went on to kill his own cellie, a point that would have proven problematic for Governor Perry if he still mattered at all in our wacko political discourse. None of these people really know me, after all, and while I feel I’ve given them nearly two decades of exemplary behavior in prison, I understand I forfeited any kind of benefit of the doubt long ago. In any case, betting on the worst angels of our nature is what they do around here, so there you go. The takeaway from this meeting was that the director’s hold placed on my file would be removed. During my next hearing with State Classification scheduled for later this month, I should be cleared to attend the Cognitive Intervention Training Program, the transition program for men returning to the general population after a long stint in solitary.

I have been thinking about this moment for a very long time — thinking and planning and predicting and hypothesizing and wargaming and trying to imagine every possible curve ball that mother prison might decide to lob in my direction. Whatever the accuracy of these prognostications, I know in a general sense that I am going to be trading one series of problems and traumas for another. Instead of being shoved into the modern equivalent of an oubliette and forgotten about for months on end, I suspect I will soon regret of the potency of correctional gaze leveled upon me; in place of an unceasing loneliness, I will be thrust into an unending crowd, with all of the violence that inevitably results when far too many primates are kept jammed together in tight confines. I have attempted over the years to stay hip to the unique politics, behaviors, and beliefs of the various families and cliques and gangs, so that I know which reefs I can swim around and detect when the feeding frenzy is about to begin, but I’m not certain if these disparate data points amount to expertise. I suspect there will be missteps. For all of that, I know I will be okay. These past two decades have been one long epic tale of trials and grievous wounds both physical and mental — and even a sort of trip to the underworld — and I’m still here. A little wiser, I hope, a little less ignorant, and if I’ve learned anything through all of this is that I know how to get up again after a fall. In any case, I have some plans for the coming months and years, and contingencies for when those inevitably don’t work out as I’d hoped, plans which absolutely cannot be actualized from inside segregation. Meaning, whatever the costs to be paid, I’m ready to begin. I’ll be discussing some of those in the coming months, and I hope you will continue to walk beside me as I step onto this new path. Onward.

2 Comments

Akash Pisharody

October 4, 2024 at 1:39 pmI mostly lurk and never comment, but this was such an incredible read Mr. Whitaker. Your hard-earned wisdom and sardonic with really generates so many quotable lines.

Manifesting nothing but the best for your State Classification hearing, and hopefully for your re-entry (at long last!) into the aboveground prison system, so to speak.

Love and hope from India,

Akash

L.Dupler

September 20, 2024 at 4:40 amAnother great read Mr,Whitaker. I learn so much more about life from your writings. Thank you very much.