Description

“We knew our sound wouldn’t fit in, as it was. They don’t call it DEDx, after all. I already knew Troy, and had huge respect for his chops. [Reference to Hewitt’s musical talent, not his prodigious sideburns.] More importantly, I dug him as a person. In here that’s rarer than bacon. I knew I had to work with this guy, and that neither of us was entirely happy with how our bands sounded. So I asked him if he wanted to collaborate on something different.”

“After spending countless minutes (at least five per day) mastering the guitar, I was at first dispirited at the idea of embracing the lackluster stylings of the bass. All that hard work would be for nothing. Then it occurred to me that now I would have more time to sleep.”

“Honestly, when Steve and I started writing music, I questioned whether two people with such different musical backgrounds could mesh creatively. He brings these metal sensibilities that are worlds apart from my background in jazz and blues. Turns out the counter-culture spirit of our respective genres is what matters, and what works, especially in here. Prison is geared toward discouraging us from accomplishing anything. When you listen to these songs, I hope you hear a grin and a middle finger raised toward that.”

“Begin at the beginning,” the King said, gravely, “and go on till you come to the end; then stop.” —Lewis Carroll.

“Forget all about that macho shit, and learn how to play guitar.”—John Mellencamp

|

| Steve plays an Ibanez Iron Label, tuned to a B standard or drop A tuning |

|

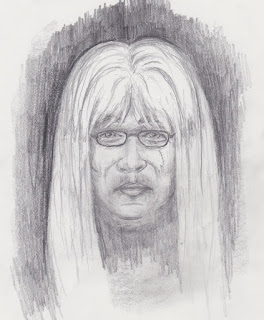

| Lars Snow |

|

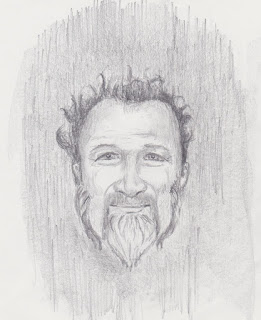

| Clamor |

|

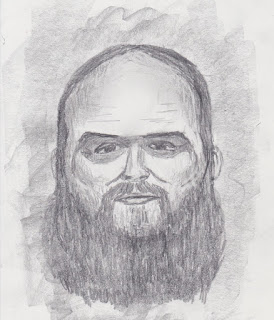

| Troy Hewitt |

|

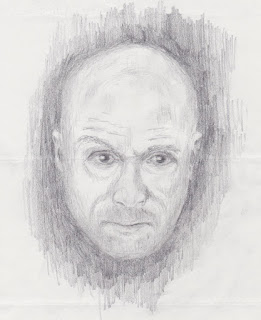

| SteveBartholomew 978300 Monroe Correctional Center P.O. Box 777 Monroe, WA 98272-0777 |

No Comments