History has shown time and time again that jailhouse informants will do anything to gain favor in their cases, As one judge put it, “[jailhouse informants]” willingness to do anything includes includes not only truthful spilling the beans on friends and relatives, but also lying, committing perjury, manufacturing evidence, soliciting others to corroborate their lies with more lies, and double-crossing anyone with whom they come into contact, including – and especially – the prosecutor.” Words by Judge Stephen S. Trott, U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit. He concludes, “[o]ordinary decent people are predisposed to dislike, distrust, and frequently despise criminals who “sell-out’ and become prosecution witnesses.

Jurors suspect their motives from the moment they hear about them in a case, and they frequently disregard their testimony altogether as highly untrustworthy and unreliable, openly expressing disgust with the prosecution for making deals with such ‘scum.’ Words of warning for prosecutors using criminals as witnesses, 47 Hastings L.J. 1381, 1383 (1996)

Even if substantive, it seems the sole use of this kind of circumstantial hearsay evidence to obtain a conviction is akin to rolling the dice and hoping to hit your number in one try. It’s what I term: “by any means evidence.” — You know, the kind of evidence used to obtain a by any means necessary conviction.

While Judge Stephen S. Trott’s words of warning about this class of by any means evidence may hold true to some ordinary decent people’s beliefs, in the years since, history has shown that this view has had no sway over jurors’ fact finding roles.

According to a 2005 study by The Center for Wrongful Convictions at Northwestern School, it examined 111 cases in which the defendants were exonerated. The study found that in 51 wrongful capital convictions, each one involved perjured informant testimony accepted by the jurors as true.

Law Professor Samuel Gross’s study on exonerations likewise reports that nearly 50 percent of wrongful murder convictions involved perjury by someone such as a “jailhouse snitch or another witness who stood to gain from that false testimony.” Samuel R Gross: “Exonerations in the United States, 1989 through 2003.” 95 J. Crim. L & Criminology 523, 543 – 44, (2005)

A 2014 Northwestern University study found that 45.9 percent of documented wrongful capital convictions have been traced to false informant testimony. This makes “snitching” the leading cause of wrongful convictions in U.S capital cases. The National Registry of Exonerations, founded in 2012, lists 2,842 exonerations across the country since 1989, an average of 88 a year. By 2016, it found that 81 of 116 death penalty exonerations involved perjury or false testimony by incentivized witnesses— an increase of up to 70%.

These studies not only indicate this class of ‘by any means’ evidence is a prevailing pondemie, more importantly to the subject, it indicates that when defendant’s do go to trial, numerous exonerations reveal just how often juries believe lying criminal informants, even when juries know that the informant is being compensated and has an incentive to lie.

With these fantual numbers in mind, what would you say about a case that was brought before a jury wrought with nothing but the use of hearsay testimony of jailhouse informant witnesses/liars?

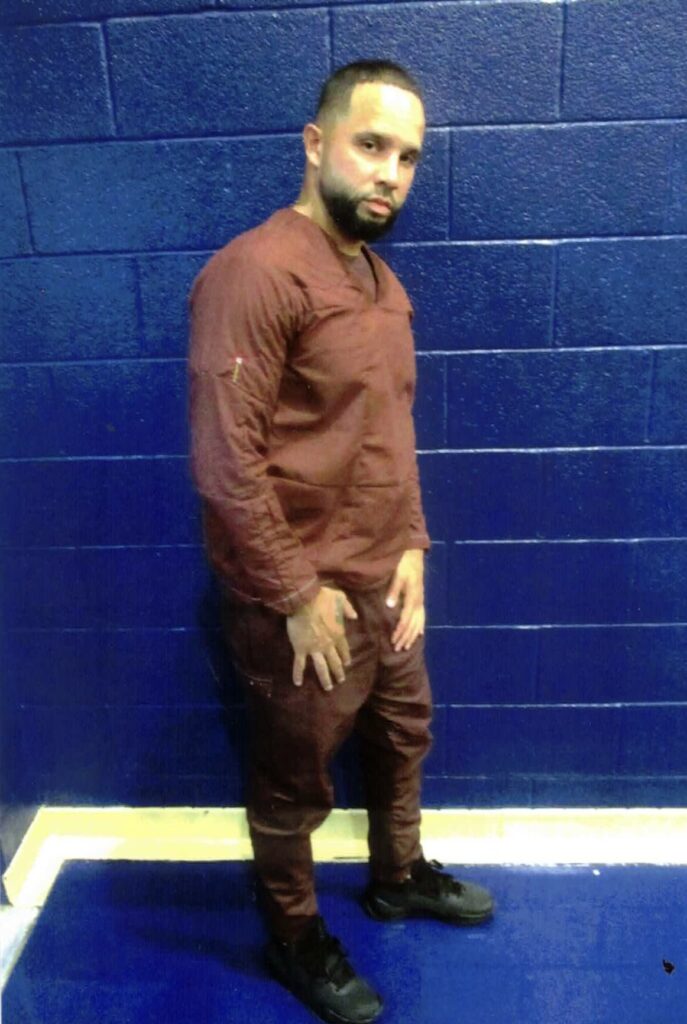

Welcome to Commonwealth of Pennsylvania v Norman M. Vega (Berks County) where I have been persistently rigoreus in fighting to prove my innocence against a conviction obtained through— you guessed it, the sole use of this by any means evidence.

In my struggle to prove my innocence, I have learned that this justice system deals in suffering and is not satisfied until someone, guilty or not, suffers. Police and prosecutors across the nation have repeatedly demonstrated that they will accept any conviction. The more high profile the case, the more likely this is true. The numbers don’t lie: there are wrongful convictions that may have been avoided had police or prosecutors valued truth over success and worked to establish whether or not the defendant they sent to prison was, in fact, guilty. Or in my case: innocent.

In a judicial system where the expense falls solely on the taxpayer, the prosecutor stands to lose nothing by “rolling the dice” and everything to gain from the media attention… Because, as studies have shown, in using this kind of ‘by any means’ evidence to obtain a conviction:

“It’s not the truth that matters— it’s what the jury believes.”

No Comments