Episode One: Seriously Out of Place

When the end finally arrived, it was almost disappointing in its brevity. I wasn’t exactly expecting applause or even a pat on the back. After so many years anticipating this precise moment, it did seem a little weird that nobody else in the room appeared to understand that a genuinely momentous dividing line had been crossed. One minute I was stepping carefully out of the dingy white Econoline van, attempting to avoid the indignity of face planting mere steps from a certain kind of freedom, draped as I was in the full regalia of an administrative-segregation prisoner on transport: heavy leg irons linked to a belt chain locked to handcuffs. The next I was standing in a sweltering tin-roofed shed, wondering what I used to do with my hands before more than 6,200 days living in a concrete tomb had trained me to expect to have them secured behind my back. There were people around — people not separated by gate or window or wall, and I found that some deep, lizardy part of my brain had yawned and peeked one yellow eye open and was actively tracking their locations and velocities: the portly officer rifling through the sole red mesh bag of property I had been allowed to bring with me, the trustee near the corner sluggishly pushing a broom so denuded of bristles that the wooden frame made loud scraping sounds as it skidded along the concrete. I finally settled on crossing my arms behind my back, military style, and then instantly regretted it and let them hang at my sides.

The screw was more aware than I had given him credit for. “Been in the hole awhile?” he asked, looking up from my sack of hygiene items to glance at the awkward ballet of my appendages. He had six white diagonal slashes stitched into the left sleeve of his shirt, each symbolizing five years of service. Rookie mistake, I realized at the time, not recognizing another lifer for what he was. I wouldn’t get to make too many of those going forward.

“A bit, yeah,” I admitted, resisting the urge to fold my arms across my chest.

“Well, that shit’s over with. Welcome to the transition program.”

Like so many words spoken by employees of the Texas Department of Criminal Justice (TDCJ), they were both true and not.

To say that all of this was unexpected is a bit of an understatement. 2024 began pretty much like any other of recent vintage: me, rotting in ad-seg, my keepers contorting themselves into ever more creative positions to justify my classification limbo. Unlike in past years, however, this time around I had some attorneys based out of our nation’s capital investigating the issue. If you had asked me for my most optimistic timetable on 1 January 2024, I’d have said that I would have hoped we’d have filed a Section 1983 lawsuit by September. As it turned out, things ended up being a bit simpler than I had anticipated.

As a prisoner laboring under a high-profile (HP) tag, I was fairly accustomed to random sergeants popping up at my door unlooked for. Technically, they were supposed to arrive with a handheld video camera aimed and rolling any time one of the five HPers on the McConnell Unit left our cells. They mostly stopped following this policy for me once the Warden figured out my tag originated in Austin rather than via the more traditional avenue of being a violent dumbass. Ditto for the required shakedowns every 72 hours. It had been at least two weeks since I’d had an employee in my cell, so when sergeants C- and M- showed up on 1 February, I merely sighed and steeled myself for what I hoped was only a minor degree of unpleasantness. It took me a moment to notice that they were both in dress grays, and looking very inspection ready.

“Audit?” I asked hopefully as M- inserted his brass key into my door and opened the tray slot.

He gave me an amused smile. “You really pissed someone off.”

Cue the alarms in my hypothalamus. “What do you mean?” I asked, stalling for time as I cut a quick glance around my cell, cataloguing the minor items of contraband in plain sight.

“Somebody’s here to see you. Get dressed.”

“‘Somebody’ have a name?”

“Yes.”

“Warden?”

“Somebody important. From Huntsville.”

I’d already figured that part out. They’d known the day before that something was happening — that’s how they knew to wear the fancier uniforms. I hustled off to throw on my jumpsuit and quickly stuff my speaker and multi-outlet into a slightly better spot. I gave myself a quick inspection in my mirror to make sure I was sufficiently presentable to be shown into the presence of some portion of the deific pantheon of Tartarus. The office they led me to was normally occupied by 12-Building’s Major and his harem of secretaries. On this morning, the open area outside the office proper was packed with a prisoner’s worst nightmare: men in bad suits carrying large folders, all of whom paused their conversation and swiveled their heads to stare at me as I rounded the corner. It was so choreographed it felt like something they must teach at cop school: Contemporary Synchronized Glaring in the Penal Context, lecture at 9am. I performed a quick facial survey before recognizing Bobby Lumpkin, Director of the Correctional Institutions Division, and Bryan Collier, Executive Director of the entire TDCJ. So, Ares and Zeus, basically, to continue the metaphor from earlier.

I’m not sure a citizen of the United States can really understand in a genuine, experiential way the drastic gradient in power that separates a prisoner from a warden, let alone a director. I initially thought about making the comparison between a Fortune 500 CEO and the guy that mops the floor at night, but this parallel wasn’t even close. In that analogy, the worst that can happen to you if an exchange turns sour is that you might end up looking for a new job. There aren’t any real rights that prisoners possess in the face of a director. There are supposed to be — you erroneously believe that some must exist, coming as you do from a place where the weak have protections and means of redress — but if you were to ever spend any time in a Southern prison you’d recognize that on this side of the fence reality is whatever the big man says it is, and morality, where it exists at all, is distributed unevenly. I know I have readers from less liberal portions of the planet, so I suspect some of you understand only too well exactly what I am talking about. Frequent readers of this site will have been exposed to some examples of the cruelly inventive ways in which prison employees have meted out vengeance upon those offenders that displeased them in some fashion: men locked into cells without food or water for days, often leading to long-term health consequences; medical visits denied or permissions to attend programs cancelled; inmates escorted to portions of various facilities outside of the scope of camera surveillance and beaten; or, you know, certain authors thrown into segregation for years on end without rational justification. These things happen all the time, just because a regular guard got pissed off. What could a director do? Practically anything they want.

So, yeah, anxiety was present in the milling crowd of my thoughts, tossing out casual reminders of the very real possibility of spending the rest of my natural life in solitary if I flubbed the interview. So too was an angry voice insisting on some measure of accountability for what I have endured these past six years: the dozens of ranking officers that have privately commiserated with me over my classification status, while simultaneously towing the line required by Huntsville; day after week after month after year of being confined to the equivalent of a cave, struggling to meet my basic needs; being told I was a threat to the safety and security of the prison without the tiniest shred of actual evidence. Zora Neal Thurston once wrote that if you were silent about your pain, they’ll kill you and say you enjoyed it. This is a sentiment I suspect every writer on this site understands and wrestles with, this feeling that we must bear witness to what is done in this nation in the name of justice.

Nevertheless, this was a voice that I knew I had to silence. All of those injustices? They are allowed to happen for a variety of reasons, but surely one of the most potent is that everyone in the administration — from the directors down to the lowliest officer — is aware that no matter what actually happens behind these walls, the prisoner is going to bear the moral blame for it in the eyes of the public. A prisoner got smashed on by a pack of screws? Well, he shouldn’t have robbed that house, then, no? An inmate died of heat exhaustion after the index values topped 130F? He should have thought of that before he assaulted that woman in the park. “Don’t do the crime, if you can’t” — well, you know how it goes. This way of thinking is remarkably attractive — even for me at times, when surely I should know better. Reductive arguments usually are. Still, if we are morally responsible for whatever actions placed us under judicial sanction, then so too are the guards that assault the men under their care. You can’t make deontological or absolutist moral claims about free will or responsibility if they don’t apply to everyone equally. This isn’t the way my world actually works, however, and no amount of explanation or argument on my part was going to change the fact that when someone like Mr. Collier sits down in front of a prisoner like me, all they see is one event. I will forever be defined by 10 December 2003. Maybe I should be so marked. I just wish there was room in the minds of some of you for improvements.

It seems like I have to remind myself of this on occasion. Like so many of us, I live in an informational silo of my own construction. I live around criminals. Compared to the vast, vast majority of my peers, I am — or I perceive myself to be, though I think I can successfully defend the position — morally superior. I live quietly, with honor. I am straight in my deals. I mind my business, even as I’m seeing everything that is going on. I help others regularly, without showmanship and without expectation of compensation, either from the beneficiary or from the universe in general. Many of the officers treat me as someone they like and trust, within the bounds placed upon them by Huntsville. It is easy to slip into the mental position that I am “better” in various ways than most of the men around me. Every once in a while, when this sort of feeling manages to get a little momentum behind it, I have to in essence wash myself clean of every good and decent thing I’ve done over the past twenty years and step back into the space of what someone would think about me if all they had to go on was my Wikipedia page. It’s not hard to find my way into this realm. I have lots of scars. I just have to touch them to remember the damage I’ve done.

For all of that, Collier was fairly decent to me. He didn’t let the sergeants remove the handcuffs or the leg irons, but beyond that he was civil. A number of points became clear to me over the course of the interview, which lasted around ninety minutes. First off, he was not going to give me any confirmation that Abbott had ordered the TDCJ to keep me in solitary confinement. Lawyers were involved, after all — and in any case, he didn’t know about our source in Austin that ultimately told my camp about what was happening. Second, he’d been thinking about releasing me for roughly two years. On two occasions over the past eighteen months I’d been taken to the Major’s office to be interviewed by some psychologists on Zoom. One of the little file headings on the screen was labeled “Dynamic Risk Analysis,” so I had always figured that these interviews were a part of some internal cover-your-assery that might result in my eventual release. Collier admitted that this was in fact the case: he had ordered them, and the positive reports generated over nearly two years were the reason we were speaking.

This realization cheered me. Maybe I would always be a colossal failure to Mr. Collier, but I wasn’t any more dangerous a failure than the 134,668 other losers he managed successfully every day. He was here, I realized, because he’d already been leaning towards releasing me, and was simply attempting to drive any potential deviance out of the ultraviolet and into his detectable range to ensure that I wasn’t going to embarrass the guvnah if I were allowed out to play with the other miscreants. Collier wouldn’t confirm a final decision to release me during our little chat, of course — people in power won’t be rushed into making decisions, especially not by people like myself.

The closest he came to showing his cards was when he asked me about my future plans. Ever since the government handed out free money during the pandemic, I’ve been saving up in order to work on another graduate degree, this time a Master of Science in Psychology. (More on this in early 2025, but if this sort of thing interests or matters to you, I could really use some financial support. I have enough funds to start the program, but nowhere near enough to finish it. Although I haven’t received any such help from this site in years, I’m stepping out in faith that I still have a few of you out there who believe in what I’m trying to do here. Any donations made here will be supervised by my father.) I was in the beginning phases of applying to this program and mentioned to Collier that it would be really helpful to know if a transfer of units was imminent. Attempting a graduate degree from prison isn’t easy: there are exam proctors we must obtain approval for, transcripts to be ordered, checks written, books purchased, studies from scholarly journals ordered. Getting moved to a new facility would require changing large portions of what I was in the process of setting up. Collier thought about this for a moment and said that he thought it might be a good idea if I waited a little while to begin the program. I felt a massive tension down in the core of the earth begin to unwind. I remember taking a deep breath and looking down at the tan carpet for a few seconds, before glancing up to find Collier staring at me intently. He nodded. I recognized I was dismissed, so I stood up and shuffle-clanked my way back to my half-life. He didn’t shake my hand, but then, I didn’t expect him to.

The feeling of impending release that enveloped me in the Major’s office began to dissipate as the days turned to weeks. I tried not to question my memories of that day, nor the conclusions I had drawn, but I admit this became more difficult as February turned into March. Memory has as much to do with our present state of mind as it does with any event from the past, and as my thoughts settled back into surviving in the wasteland, they turned grayer. My one polestar was that comment about the degree, but I started to think that maybe my definition of “waiting a little while” was massively divergent from Mr. Collier’s. Maybe, to him, I’d only been in solitary a little while.

I knew that I was supposed to see a member of the State Classification Committee (SCC) in either late March or early April. They call these little events “hearings,” but that’s a bit grandiose. For the most part, a decision to remand someone to ad-seg or promote them to population has already been made before the inmate walks into the room. There are always three members of the “committee” (again, you kind of need to squint a bit in order to make that label look like it fits): the representative of the SCC; a ranking member of that unit’s security apparatus, usually a warden or a major; and a third member of the staff, sometimes a unit-level classification secretary, but occasionally a chaplain or a teacher from the schoolhouse. These thirds never matter, and seldom say anything. I’ve often thought of Calvino’s Il cavaliere inesistente when I watch these people: empty spaces in loose suits. I had seen SCC twelve times since my commutation and had grown accustomed to some variation on the following theme. First, I enter, escorted by the normal pair of correctional officers, but also trailed by an additional screw aiming the hated handheld camera, who in turn is stalked by some species of ranking officer, usually a captain or major. This corrective conga line always makes the representative from Huntsville do a double take, and then turn to give me a long, judgmental glare: oh you scumbag — what are we going to do with you?

This stern disapproval inevitably converts to confusion after they thumb through my hefty file and fail to locate the expected staff assaults or escape attempts. The searching through various folders grows more intense as they try to locate any reason whatsoever for my presence in the room. In recent years, I’ve actually had several wardens attempt to speak on my behalf, and on at least two occasions the SCC representative had listened intently. This always ends once they find what I now know to be “the Director’s hold,” and I’m unceremoniously exiled back to my little concrete tomb for another six months.

I hadn’t been hopeful over an SCC hearing in years. In the week preceding 28 March, I vacillated between periods of cautious optimism and a malignantly misanthropic fatalism in almost daily cycles, to the point where I was finally able to step back from the fray and mock myself: look at yourself, you fool — look at the knot they have you twisted into. I joined the line of prisoners in 12-Building’s hallway firmly in the grip of expecting a letdown.

That changed almost immediately when Major Tanner saw me. He said a few words to Sergeant B- and then approached. B- produced the camera but Tanner motioned for him to pause. “Director of Class’ is here for you.”

“Fitzpatrick?” I asked, incredulous.

“Yep.”

“I knew him when he was naught but a lowly major.”

Tanner laughed. “Well, this lowly major is questioning if you know what it means that he drove all the way down here for you.”

“Why yes, boss man, I’d love to buy your shiny new bridge,” I replied, internally shouting down the chorus of hopes that had just broken into song.

“Enjoy this, you fucker. Smile for a change. Good luck.” He actually patted me on the back, which I would have appreciated more if he hadn’t immediately thereafter ordered me to be placed in leg shackles. Still, maybe were friends now?

I spent the next fifteen minutes waiting outside of the Lieutenant’s office near E-Pod, ruthlessly swatting down the butterflies that kept spawning annoyingly in the region of my stomach, and trying to ignore the scent of what I swear was peach-scented sawdust wafting off the guard with the goofy calligraphic mustache holding on to my left arm. I don’t know how pulverized Georgian woodchips got its sleeve caught in the American scent merchandizing machine and ended up getting sucked into a scent for aftershave, but the man had apparently bathed in the stuff, and it was pretty close to nauseating. I wondered if my annoyance was obvious to the lens staring at me and did my best to wipe my topology clean, which reminded me that it might just be a wiser plan if I went ahead and cleared away the inside, too. I thought about all of my friends on the row, both alive and not, that would have given a great deal to be placed in a moment like the one I stood in the presence of, and soon I was settled down and channeling my inner Zeno, ready for whatever would come.

Eventually, I was ushered into the office by a secretary, who, it would turn out, was the Director’s personal assistant. I had met with then-Major Timothy Fitzpatrick a few weeks after my commutation. He had summoned me to his office in response to a small flood of I-60s I had been sending out to basically everyone seeking an answer as to why I was still in ad-seg. I don’t know what he was aware of regarding the political dimensions of my problem, but I don’t believe he was in the loop. I say this because everyone I’ve spoken to about him has pegged the guy as a straight shooter. He came off that way to me back in 2018, when he told me he had no way of telling why I had been remanded to ad-seg, that there was nothing that explained the situation that he could see on the computer. He was promoted to Assistant Warden not long thereafter.

He seemed to remember me, though — or maybe he was now very much inside the loop. The hearing was more formal than was the norm, which made me wonder if they were recording the event. Fitzpatrick reviewed my disciplinary history utilizing the emotional patois and camber of Prison Authority Man, and his secretary said some nice things on that front that were only a semiotic shade or two away from an actual compliment. The Head Warden was asked for input, and he remarked that he’d never had any issues with me, which, in my world, amounts practically to hagiography. Fitzpatrick finally put the paperwork down and gave me a long look.

“You didn’t have a lot of choices the past few years. When you did, you chose well.”

Whatever nice glow of appreciation I was feeling over this comment was immediately snuffed out by what came next.

“I’m a young man, Mr. Whitaker. You understand what I mean by that?” He was right — he was young, still in his 30s. His father, I had been told, had also been a director, and Fitzpatrick fils had attended Sam Houston State University’s criminal justice program, the source of nearly all of the wardens in the state. He had to have been one of the youngest wardens in the system’s history, and it wouldn’t surprise me if he ended up as Executive Director one of these days. I thought about all of this as I mulled over his comment. Of course, I knew exactly what he meant. The question was whether I admitted to this, or to what degree. When speaking to people in power, there is some wisdom to the aphorism “least said, soonest mended.” There is also a cost to a calculated silence being noticed for what it is, though, so the coin finally landed on me acknowledging his point openly.

“Yes, sir,” I said finally. “It’s not a subtle point. You are saying not to make you look stupid putting your signature on my I-189; that if I do, you are going to be around for a long time to make me regret it.”

In response, the Director of Classification of the largest state prison system in America pointed his finger at me, and his thumb descended like the hammer of a revolver: blammo. My release papers were passed amongst the committee for signatures amidst the pong of imaginary gun smoke, and I was sent along my merry way.

For very merry it was: I felt like I was floating as I made my way back to the pod. Everyone in line had heard Major Tanner’s comment about the Director making the trip for me, so I entered my section to see most of my peers at their doors waiting for my return. I didn’t even attempt to hide my smile.

It was interesting for me to hear which people congratulated me, and to what degree of sincerity their words amounted to. Some people I had thought of as friends proved to be less so than I had imagined, while a few others surprised me.

People are funny sometimes. I felt a little tinge of sadness lurking around the campfire glow of my relief that some of the people I’d been kicking it with on the God Pod for eighteen months couldn’t see past the solipsisms of their own misfortunes sufficient to share in my joy, but I had done far, far more time in solitary than anyone else in my section and I wasn’t going to feel sorry that my ticket had finally been punched. It was a good lesson, though: whatever I have going on in my own life, if I call someone a friend, I need to make sure I don’t pollute their triumphs with my own fatalism.

I knew that I would have to attend the TDCJ’s transition program before I could be moved to population. I had been questioning people for years about this program, so I felt I had a decent understanding of how it operated. Which is why I found myself somewhat surprised to be standing in a shed at the Ellis Unit in Huntsville, watching that portly officer with all of the stripes search through my belongings. I had always heard that the program was housed at the Ramsey Unit. Everyone had told me this, but apparently everyone didn’t know that Ramsey was where they sent the inmates they weren’t worried about. The high security transitioners, the ones with staff assaults “beyond first aid,” the people with escape security precaution designators, the offenders with multiple felonies for possession of cell phones or shanks, and, apparently, the people who write essays about all of the above, they all get sent to Ellis, former home of death row.

I had heard stories about this facility from the older guys on the row for years. Prior to the system moving all of the condemned to the Polunsky Unit in 1999, the better performers were able to live in a communal environment. They had access to the dayroom, had cellies, and worked in the garment factory. I had sometimes imagined what this might have been like: what were the dimensions of the cells? Were they like the ones I had lived in at the Coffield Unit, which was built of the same materials and in roughly the same era? What were the dayrooms like? Who would I have hung out with, and what would we have done?

Prison Land is a smaller place than it seems, or maybe some god or avatar of fate is having a bit of fun with me. Before I could be placed in a cell in B3, home of the Cognitive Intervention Training Program (CITP), I had to meet with unit classification, i.e., the wardens. This trio was apparently too busy to see me, so I was told I was going to be housed in a solitary cell on J23 wing until I could be processed. I was told that this might take a few days. This turned out to be less than four hours, which basically and inconveniently amounted to just enough time for me to go through about six bucks’ worth of cleaning supplies as I brought the place up to my personal level of sanitation. Afterwards, I sat at the door with a cup of coffee and thought of all of the cons I had known who might have lived in this very cell. (It was J23 206, by the by. If any of you older cats still on the row happened to live there or remember someone who did, I’d be interested in knowing.) I don’t believe in ghosts, but I felt them all the same.

The wardens seemed to know who I was. They went through the customary lifting of the hood and tapped on various aspects of my personal story, which really just boils down to an exercise in establishing the pecking order: them the peckers, me the pecked. They seemed to think that my greatest accomplishment in life was not being dead. “…come celebrate / with me that everyday / something has tried to kill me / and has failed,” I responded. Zero-two, or the First Assistant Warden in civilian, was looking at me like I’d just sprouted a second head. “It’s… uh… just a poem. Lucille Clifton?” I added. Clearly, they were not poetry fans. I should have gone with Merle Haggard or something. The only datum I took away from the chat was that the cursed high-profile tag had not been removed from my file, only “modified” to allow my release from ad-seg. I chewed on this morsel for a moment, beginning to taste some subtle notes of bitterness amidst all of the sweetness. I pushed the matter and was assured that the tag would not impact my life in any negative way. “Then why not just remove it? What is the point of having it, if it is not designed to limit me in some way?” The three shared a glance. “Above our pay grade,” one finally said. Amazing how many ways there are in this world to say “fuck you,” isn’t it?

Units like Ellis are built around a single long hallway, somewhat predictably referred to by its passengers as the “highway”. Unlike newer prisons, where the goal is to throw up a bewildering profusion of barriers, walls, fences, and partitions for the purpose of subdividing the population into more manageable sizes, everything here feeds off the highway more or less directly: the wings branching off east and west, the highway running north/south. The terminus on the north end is some kind of gym, with the chapel on the south; both would turn out to be off limits for the men in the program. Along the concrete floor were painted bright yellow lines, each roughly four feet from the walls. Inmates in transit must walk between the lines and the wall, I was told on that first day: deviation without permission could result in a code 27.0, or “out of place” disciplinary report.

My maiden trip down the hallway towards my apparently now ready cell was a feast for the eyes. After being buried in various isotopes of 12-Buildings for 39% of my life, the highway felt positively exciting to my dark-adapted eyes and mind. Men were packed in the windows of each hallway’s dayrooms, screaming at others across the expanse or rapidly flashing sign language; others paraded to and fro, mostly on the correct sides of the yellow demarcations but not always. Then there were the murals — oh, the murals! Whatever officer ran the inmate paint crew was obviously endeared with the idea that anything worth doing was worth overdoing, because there was a new one plastered on the redbrick walls every fifty feet or so. Big cats abounded, but there were also some raptors of various degrees of ferocity, plus a bear or two. Each stared stonily at passersby. Each was adorned with what I suppose were meant to be pithy maxims: Falls are inevitable, defeat is optional. Tomorrow is another day to try harder. Fly higher, no matter the wind. It took me a few trips down the highway to notice that every single one of these aphorisms was value-neutral: they could just as easily be used to encourage criminal behaviors as to promote or motivate moral ones. B3 was near the southern end of the hallway. I could see from the windows that the dayroom seemed to be packed with offenders. The officer manning the doors — known imaginatively as the “turnkey boss” in the vernacular — opened the gate and nodded. I walked in to see another locked door leading to the dayroom on my right. To the left of this was a staircase that ascended to the second floor. To the left of that I could see a long line of cells extending forward into the distance. I had been assigned to cell 309, the ninth cell on the third floor. I’d spoken to dozens of guys over the years about what constituted proper procedure for new arrivals, so I felt I understood the rules for checking in. First, I was to drop my bag off at my cell. If I had a cellie, I was to meet him and establish ground rules for acceptable behavior. Two, I had to make myself a cup of coffee and hit the dayroom. People who have bad reputations avoid public places as much as they can, so by going quickly you are making a statement that you don’t fear anyone or any rumor: you are there to settle accounts immediately, so to speak. Easy enough, right?

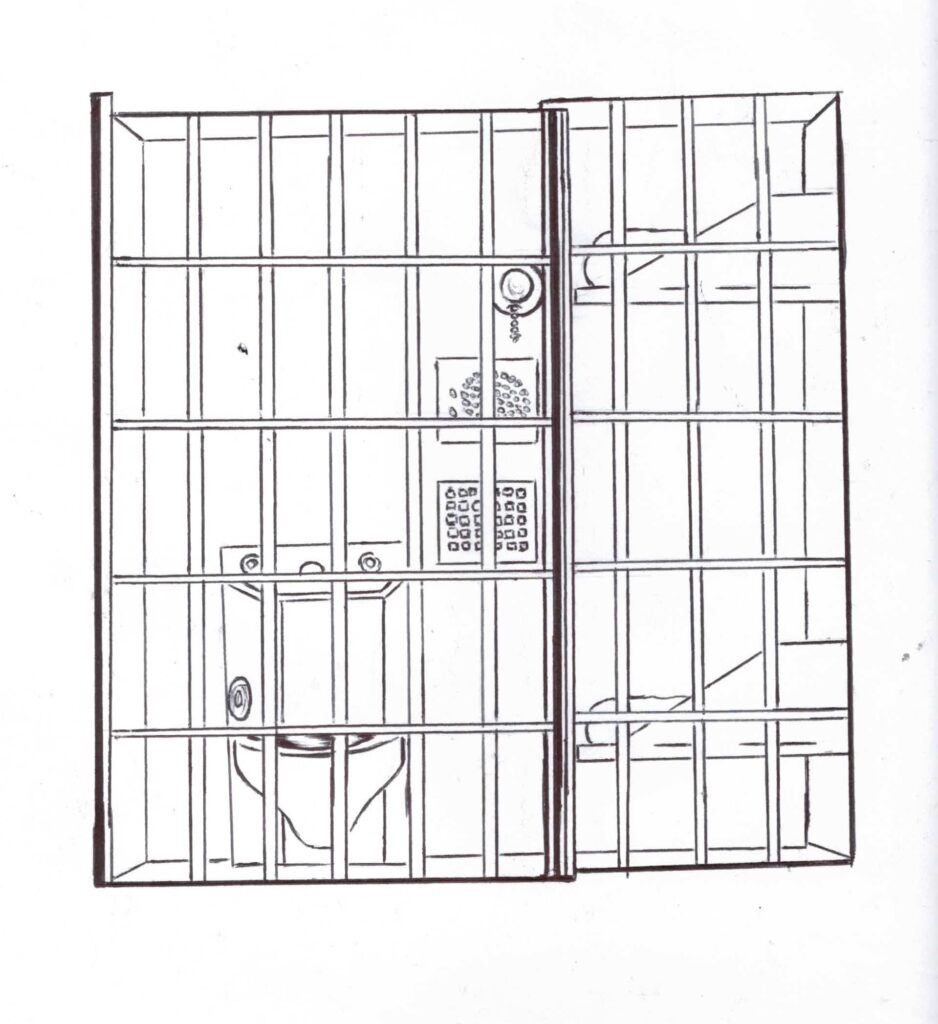

The staff at Ellis had not received the same memo, apparently. After schlepping my bag and mattress up two flights of stairs, I located my cell — which was closed shut. I had been assigned to the bottom bunk, and I could see through the bars that this was in fact empty. I saw a mattress and a few odds and ends belonging to my cellie. The man himself was absent, however. The cell was one of the old styles, meaning: six by nine feet, i.e., very, very small. They’d replaced the old porcelain toilet with a stainless-steel sink/toilet combo. That was the only amenity. Of desks or shelves, none were to be seen. We didn’t even have a light bulb in the fixture, I noted. It wouldn’t take me long to figure out why, alas. (Below is a simple drawing of what the cells look like when seen from the front. There’s not much there, because in reality that is all there is. My thanks to WestSide Los for the art.)

My rapid inspection complete, I looked back down the tier towards the staircase, where a set of bars protected the officer picket. Nobody was present. I looked to the right. All of the cell doors were similarly closed, and nobody else was in sight. Okay, I thought: battle plans work great until somebody punches you in the face. I stood there for a few minutes, trying to weigh the possibility of a guard showing up to open the doors verses the social cost of me looking like a dumbass noob for standing there pointlessly. Sometimes when I’m feeling anxious, I play with numbers. I’ve written about this before, about how I’ve done this since I was a kid. I tried to decide if 309 had any intriguing qualities to it. I couldn’t think of any. (I still can’t — it’s a pretty boring number. The only two on my tier that I came up with something for were 313 and 319: the first is the only 3-digit palindromic prime to be palindromic in base 2, and the second can’t be represented as the sum of fewer than 19 4th powers. The shit some people come up with when terror and boredom share a bed.)

After a few minutes of indecision, I trudged back downstairs and posted up in front of the dayroom bars, pretending to watch the sports television but actually trying to get my pattern recognition algorithms to make some sense of the chaos amongst my peers. When I was last in population, there was a multi-tier system for who sat at what tables. Race, that old bullshit heuristic, was always tier one. This was followed by gang or family affiliation, and on some occasions which neighborhood one lived in. In this area my expectations were similarly detonated, for I could make little sense of the ethnic layout before me. In the back left corner, two tattoo artists, one white and the other Hispanic, worked on clients, both black. To my left by the window, a group of four men shared a joint — two African Americans, one Hispanic, and the last Caucasian. The tables were mostly similarly mixed, though little pockets of homogeneity did exist. It seemed… nice. There actually was a division of sorts running underneath the currents of the obvious, but it wasn’t something that I could have noticed on that first day.

As I stood there taking it all in, I noticed that a dark-skinned Hispanic man had begun to stare at me. I looked back — and immediately felt I recognized him. He was obviously thinking the same thing — I could see him trying to place me as well. It came to me after some reflection, and I smiled. “Maya,” I mouthed, and he returned the smile and leapt up, rushing over to the bars. I said my name to him as we clasped hands through the bars, just in case he had forgotten. I had lived above him at the Michael Unit in 2018. He was a hell of a character. I remember one weekend Big Jeff, one of my neighbors, was trying to knock a small hole in the concrete wall separating his cell from his other neighbor, Polish Karl. I’d been hearing the tapping all day, as he chipped little pieces off the partition using the central axle of the fan as a chisel and the fan motor itself as a hammer. This can be done but it takes a very, very long time. Maya had heard the racket and hollered up to Jeff in his broken English that he had some “mucho betterer” tools. He wasn’t joking. I was in the dayroom, so it fell on me to assist with the transfer. The first item consisted of a for-real hammer head tied down to a thick magazine for a handle. The “chisel” was the blade of a lawnmower, all 18 inches or so of it.

Big Jeff and Polish Karl had made short work of that poor wall. “Todavia recuerdo este pinche pico que me mandaste,” I told him, laughing. “Ay, esa mierda. Finalmente me chingaron con este jale in 19.” Maya had arrived a little more than three months before me, so I mined him for information. The first bit of unpleasantness he conveyed was that my cellie, a guy from Lubbock called Orlop, was a smoker. I don’t mean of nicotine — in this world, a smoker is another word for dope fiend, usually of K2, but also potentially of PCP or fentanyl or some combination of the three. The second was that this supposedly four-month program could actually take upwards of a year, depending on how long the waiting list was for the actual classes. Beyond that, there didn’t seem to be much in the way of actual transitioning. Absent were the phases we were supposed to process through — not having a cellie at first, for example, or only being allowed access to the dayroom after a period of adjustment. Even from just a few moments’ exposure, I could see that the administration really should have named it the “toss you immediately to the sharks” program. I felt a little stupid for ever having believed that the TDCJ could have ever understood such abstract concepts as phases, or that — I don’t know — maybe people who haven’t had any physical contact with others in years might have some issues with suddenly being plunged into a room packed with eighty other large mammals. That would have required a modicum of empathy, and we certainly can’t have any of that liberal nonsense down here, can we?

I was still talking to Maya when a guard showed up to conduct the 1:30pm count. He let me in the dayroom after writing my name on the roster for 309b. Maya invited me to sit at a table with him and a couple of other Hispanics. I thought fast. If I sat at their table, was I going to be labeled some kind of Mexican wannabe? This was always a possibility, and on a couple of occasions over the years I’d had to deal with some of the more Aryan types claiming I was “half Mexican” because many of my better friends were Hispanics. I didn’t want to be rude to Maya, however; for all I knew, he might end up becoming an ally. I glanced over at a table near the north wall. I had seen a couple of tatted up white dudes sitting together underneath the movie television. It was the only such grouping I could see. Most of the other white guys in the room didn’t look like leader types, but these guys had all of the right kinds of tattoos to imply otherwise. I made a decision. “Dame un momentito,” I told Maya. “Ahorita te hablo. Tengo que arreglar algo primero.” He nodded in understanding. I approached the table and introduced myself. The one with the lightning bolts tattooed on his eyelids was called Lucky, and the guy with the Viking-esque braided beard was called Polar Bear. I gave them the spiel: I was recently released after seventeen years in the hole; I was a solo, meaning: no gang or family associations; and I was ready for my heart check, i.e., ready to fight whoever they wanted, to show them that I was willing to fight, period. The pair shared a glance.

“You been in the hole awhile, bro?” Polar Bear asked. This was the second time someone had asked me this, so clearly I was not hiding the massive reservoir of strangeness I had accumulated over the years very well. I gave him the same answer I’d given to the guard.

“Yeah, well, ain’t nobody does solo checks no more,” Lucky responded. “‘Cept maybe at Beto,” he added, referring to a prison southwest of Dallas notorious for its culture of heart checks.

“If you get into trouble, you fade your own heat, but we won’t let nobody clique on you,” Polar Bear added, clapping my hand. “You’re good, bro.”

And just like that, I was in. I spent a few more minutes talking to them both. I felt like I knew Lucky from somewhere, but I couldn’t initially place him. It would take us awhile to work out that we’d both been at the Coffield Unit at the same time. He’d lived on a floor below me, so we’d heard each other’s voices, but never actually saw each other.

I returned to Maya and accepted a seat at their table. I noted that I felt more comfortable with a wall to my back, which told me that I was experiencing some type of anxiety. I listened to him and his friend, Nesio, talk, trying to suck down as much data as I could. I also counted the inmates in the dayroom: seventy-six on that first afternoon. There were sixty cells on the wing, meaning one hundred and twenty potential inmates in the program. I was told that they were running only two classes, however, one in the morning and the other in the afternoon, and that each had a maximum number of around twenty-two or twenty-three students. I also counted the seats at the tables and benches: there was room for just forty, or maybe forty-two if you really squeezed people in on the benches. That seemed like a potential problem, and boy, was it ever. I noted that a sign over the door read: Occupancy fifty-five. I wondered how they’d come up with that figure, as it seemed pretty random. (Fifty-five is interesting, however: it is the tenth triangular number, one of the few composed of a repeated digit. It’s also Fibonacci.) A significant percentage of the guys appeared to be smokers, because there was a steady stream of men moving from one of the electrical sockets, where they used a contraption to spark a wick, to the window, where joints were lit. It must have been potent stuff, because a number of guys were locked into awkward poses, shaking and spasming as they held onto the wall. Several couldn’t resist gravity and were slumped over on the floor. All of this happened despite the security camera hanging from the ceiling in the middle of the dayroom.

I settled back against the wall, taking it all in: the movement, the smells, the rat-ta-tat of the tattoo guns: population. Everything was gloriously alive and simultaneously corrupt, danger and freedom and enmity and camaraderie and tension and noise — so much wonderful noise, and the only partition to be seen separating man from man was the dayroom door itself. I was certain that all of this would become normal after a time — that it would even become annoying. The narcotic effects of hope only last so long, after all. For the moment, however, it felt like life, after so long without it. It is a profoundly evil thing to deprive a social creature like man of human contact. I feel like I’ve been tilting at this particular windmill for many a year, but I knew in that moment that I was going to have to redouble my efforts to help end long-term solitary confinement. I vowed not to become one of those people who escape a problem and then immediately forget about everyone else who was still afflicted. For the moment, though, I just wanted to revel in the fantastic chaos of the moment. Finally, after so many years of wallowing in the mire, I was unstuck. Finally, the road lay open before me. I was excited to see what I could make of it.

1 Comment

L.Dupler

December 30, 2024 at 2:53 amMr.Whitaker-

Extremely happy to hear the”powers that be” at TDCJ recognize your mind.

Would not be surprised to see your writings/perspectives utilized throughout the system.

Your Father must be very proud.

Keep going.