By Steve Bartholomew

One hundred seventy six months, one week and six days. A clunky clause describing a period impossible to reckon–not in any experiential sense, anyway. I try to envision it as the arc of human development spanning from fetus to high schooler, a possibility engine steadily increasing in intensity. I can no more grasp such a blur of mediated history than you can imagine the same timeline cemented to a scopic patch of fallow life, one salted with longing on a scale that dessicates the soul.

Nearly fifteen years no matter your vantage, over seven of which I’ve spent in this cell, alone. Not in solitary confinement, mind you–I don’t want to incur undue sympathy. Rather, a single-man cell, meaning I may leave it for nine hours a day, to work or shuffle about the yard.. What I lack in freedom I make up for in material security, such as we can have in here. No other prisoner may trespass upon my humble 55 square foot abode, this dim cloister where my possessions sit unmolested (the occasional search notwithstanding), immune to the usual guarantees of mistreatment and theft.

Here I may retreat from the manic doldrums of prison drama, the endless reruns of hotshot theatre in the yard starring yammerheads and witless impersonators of actual convicts and gangsters. Surrounded by reminders of loved ones and a world beyond, in this cell I may find refuge, an agreeable monotony that passes for respite. No small thing, this. Here I can create in solitude, spatially encased, my projects safe in their vulnerable stages of percolation. Even now I fail to appreciate fully how different it could be. Habituation and tedium can convince you, after years of waking alone in an enforced space, that it belongs to you. You forget the upheavals of caged life, the punctuated stasis of human storage in a dominion remotely directed.

Washington has five levels of mainline custody. Over the years I’ve slowly progressed from closed (max) to medium, then long-term minimum, which I’ve been deemed since before I started writing for MB6. Four years from the gate, goes the rule, minimum custody invokes camp eligibility.

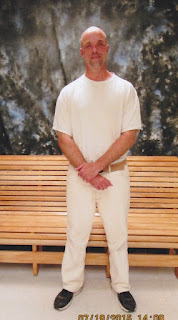

Today I leave this cell, this prison, for good. I’ve been promoted. I’m heading to camp.

It’s 6:20 AM, and my cell door opens. I haven’t been able to sleep much for the past few days–not since they told me I’m leaving this week. Anxiety born of uncertainty has shouldered aside most thoughts and charged my still moments with mental ruckus. I’ve been up for a couple hours, but the callout schedule says I’m to go turn in my state clothes at 7:30. I’m programmed to expect things to commence when the callout says they will, or later–not earlier. Nothing ever happens early here. I thought I had another hour to leisurely pack up the few remaining items in my cell. A guard appears at the cell front. “They want you now. Bring everything. You’re not coming back.”

Over the past week I have bid farewell to everyone I know in here. Some I have come to know well down the years–a few of whom you have met as well, through their writing. I will likely never see any of them again. In our world, relationships are subject to involuntary severance at any time–an eventual inevitability we’re all aware of.

My nerves are crossfiring, my hands shaking. I am cold, but sweating for no outward reason. I am struggling to stuff into my state duffel bag the proper amount of issued clothing for turn in. I am losing count, forgetting which items I’ve already sorted. Evidently I’ve packed my mind first. I ask the boss for a couple minutes to use the facilities. No telling how long the transfer process will take. “Sure,” he says.

I walk down to Receiving and Release, where there is a small gaggle of transport guards waiting to process the seven of us who are leaving today. On the counter another small contingent–urinalysis cups–is also waiting for us. One guard points at me as I approach and asks if I have to piss. I explain that I just went, that I’d figured since no one had called me in the night before that we’d do the transfer UAs on arrival. “They should have told you,” he says. “You have one hour to provide, beginning now. I have 6:32. If by7:32 you fail to provide, you will be escorted to seg instead of camp.”

Nothing stifles the waterworks like panic and concentration, wishing for an urge. The others each go through the dehumanizing process, stripping before urinating beneath a cold stare. I am the last one, alone in the UA hallway with six impatient guards. They are each trying to one-up the others, embellishing stories first of sexual oddities then weapon snafus. Not much difference between the two subjects, in delivery or themes. At 48 minutes I squeeze out enough to avoid a trip to seg. They escort me into another room, where the other six prisoners are awaiting in a cage. I arrive to a small smattering of applause. I take a bow, then a seat.

They verify our identities one last time, comparing us to our photos and making us recite our DOC numbers and birth dates. Then they walk us out into the Gate One courtyard, where I have not been since disembarking from the chain bus over seven years ago. We are in the shadow of the 30 foot wall circumscribing the prison, a centenarian behemoth of prisoner-made brick coated in peeling white paint. A monument to, and for, human suffering. The full effect is one of geological separation, even now that I know my remaining time behind this wall can be measured in seconds. Dead center is a bus-sized steel gate. An armed guard outfitted in correctional bulk stands outside his tower, looking down on us with his rifle half-slung. Escorting us is a female guard I’ve never seen before. In her mid 50s and slightly built, she has the air of a chipper tour guide.

An electric motor whirs to life, a drive chain clanks against its shroud. The enormous steel gate shudders and groans in its tracks, opening at last..

The world beyond unfurls itself, a young prodigy of a day rushing through the rectangular portal to meet me, to be experienced at last. Swerves of sap green hills like faroff dunes wreathed in cirrus, forested swells flecked with autumnal ochre and russet. Crisp brushstrokes of nature in her full scope throng behind my eyes, eluding my comprehension. For these ashen years I have tried to dream of distance, but learning to live without a horizon beneath a box-shaped sky has hobbled my grasp of panorama.

Emerging from the open gate, I am suddenly aware of being neither cuffed nor shackled, and that I am wearing my state-issued khaki clothes rather than a pumpkin suit. I glance at the other six faces in the procession. I know the story of only one, a man who has been divorced from this world for sixteen years, one more than I have been. His eyes, like mine, are widened slightly, engaged in the business of reacquainting. We are in the midst of outbuildings, a few parked vehicles. I am walking by rhythmic reflex, staring about while following the lady guard across the macadam. She pauses to key open a small gate in a cyclone fence, and we have arrived. We are at camp.

She leads us along a sidewalk past thriving vegetable gardens. We enter a door in one of several low-slung buildings, its construction evoking a real estate office more than a prison. In a large classroom medical is checking our vitals, one by one. My resting heart rate is usually below 60 BPM, but now I cannot get the hammering down to 72. I am directed to another room where a nurse delivers a ten minute soliloquy on medical policy, then asks me questions about the world (what is the date, and who is president) and what she’s said (her name, and how to report sexual misconduct) to determine whether I was listening, and presumably to judge my mental competence.

Next we follow the lady guard down a sidewalk leading to the gym, filing between manicured lawns and barked beds of coiffed shrubs. The rec supervisor is waiting for us inside, on the weight deck. He gives us a short lecture on what not to do vis a vis his department. In the door walks my friend and bandmate–the other half of Versus Inertia–who I’ve not seen in a year, since he came out here. I break from the group to go shake his hand and give him a hug. He’s stayed back from work today because he knew I’d be coming in.

Adjacent to the gym a long staircase descends onto the yard. This complex of five prisons has always been referred to as “The Hill,” but the Reformatory–where I’ve been for over seven years–is a flat-bottomed box, vision-stunting and topographically deceptive. From the head of the stairs I see the hill proper for the first time, sloping into the town of Monroe. A Chevron, an RV dealership and thrift store lie within slingshot range. In the middle distance an elevated highway weaves through the valley, its stream of speeding cars spangled with morning sun. Here is the pulse of the freeworld, arterial and glorious, the pageantry of purpose scoring its circuits in ways I could once read. My eyes ache in trying to track so much movement–thirsty, I realize, for non-prison stimuli. I cannot look away. I am speechless, overcome with a bracing awareness of my own estrangement, more or less leveled by the grandeur of quotidian life in its paces.

My friend notices I have paused, frozen but for my watering eyes. “Oh,” he says, remembering I’m sure his first glimpse of this breathing diorama . “I’ll give you a minute.”

I am dimly aware of a brainwave shift, a subtle subtraction from my perceptual backdrop. After a long moment of introspection, I realize what it is I no longer feel. Watched. There are no guard towers here, and the few cameras are watching the fence lines.

Typically, upon transferring to a new joint, I plan on waiting two weeks to a few months for my property. But here they pass out our boxes minutes after our arrival, and send us off to find our units, our bunks. Outside, prisoners wander about, unescorted. A couple prisoners who work in the property room offer to help me since the amount of stuff I own doesn’t fit on the cart, and I have no idea where I’m going.

Upon entering the dorm I am struck by its spatial economics, cramped and overlapping. A long room or wide hall, low-lidded and planted with an orchard of steel bunkbeds laden with laundry and flatscreen TVs. Natural light streams from the windows in each cubicle. Most of the occupants are either cocooned in blankets or milling about, the conversational voices of easily a dozen people sounding tightly confined in the dry acoustics of the tier, and this is how it is here, most everyone jobless and without visible endeavor or aim. Walking between the row of cubicles I inhale the pungent ghost of cigarette smoke. Everyone pauses to size me up as I pass, the newest and 43rd member of this community. I offload my boxes of property onto the floor and three of my new neighbors approach and introduce themselves, welcoming me onto the tier.

I find my bunk, a top shelf in a four-man cubicle. Alongside my upper bunk a partition extends vertically about 16 inches, separating this cubicle from the next. On the other side is another prisoner. Imagine a double bed bifurcated by a single bookshelf laid on edge, so that you sleep less than a foot away from a stranger (well, I suppose that soon we will no longer be strangers, will we).

I discover that the window in my cubicle slides open about six inches, letting in air as free as any. Although the principal view is one of the next tier and the strip of lawn between, I stand at the window for some time, transfixed. I can see the sky now, whenever I like. I can stand here all day if I wish, watching birds nod and scamper along the adjacent roof, maybe 30 feet away.

Thus begins the final four-years of my journey. And I am celebrating all I must accept. This is camp life.

|

| Steve Bartholomew 978300 MCC/MSU P.O. Box 7001 Monroe, WA 98272 |

1 Comment

urban ranger

May 12, 2018 at 8:07 pmAnother great piece painting a picture of prison life. Thank you.

Trading 'some' privacy for what sounds like 'no' privacy

must be a bit of an adjustment. But now you get to see the sky….

'I am celebrating all I must accept.'

A good attitude, Steven. Hang on to it.