Rolling up to the small Texas town of Gatesville hits different when you’re not in leg shackles and handcuffs.

I was released from the Texas Department of Criminal Justice in January 2022 after serving 19 months on a five-year sentence.

I’d given myself a little grace period of about a year to figure out parole supervision, housing, and employment before I jumped head first into advocating for the friends I’d left behind. Once those things fell into place, I no longer had an excuse to rest on my laurels.

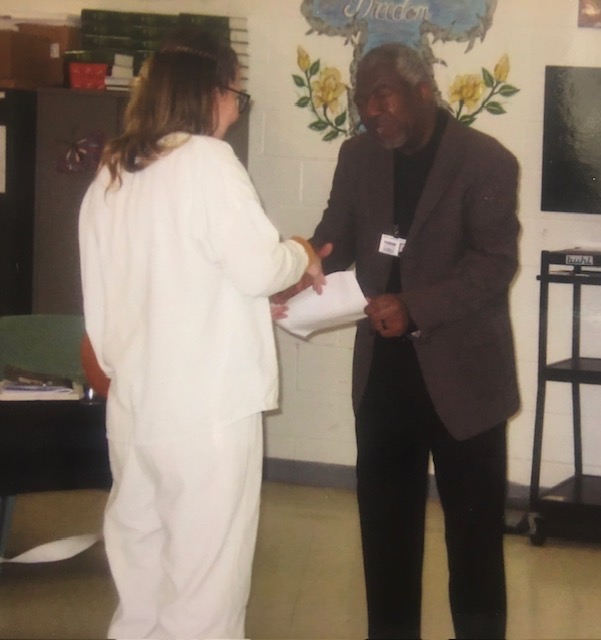

Consequently, in May 2023, I joined the advocacy group Lioness Justice Impacted Women’s Alliance and it was with this group of heroines that I traveled to Gatesville in mid-August.

We were in town to honor the incarcerated men and women who lost their lives in the deadly heat this past summer and to canvass the town and talk to people about the candlelight vigil planned for that evening.

We were also attempting to catch the attention of lawmakers and the community to let them know about the dangerous temperatures inside unairconditioned prison cells. You’d be surprised at how many people — even members of the media and elected officials — don’t know that most Texas prisons are unairconditioned.

Within days of our candlelight vigil, we got some good news. House Democrats called for an investigation into the lack of air conditioning in Texas prisons, and the Texas Criminal Justice Board announced $85.7 million that would fund air conditioning for about 11,000 prison beds. That means there are 80,000 more beds to go, but it’s progress.

Driving around town past the massive compound of prisons, I couldn’t help but think about my friends who were just yards away, wearing white elastic-waist pants that don’t fit right and a boxy V-neck shirt that feels like burlap.

Gatesvile houses about 9,000 prisoners — more than half the city’s population.

It is home to the seven women on Texas Death Row at the Mountain View Unit. It’s home to the Hilltop Unit, where my young friend Amber is serving a life sentence. It’s home to the Dr. Lane Murray Unit, where another friend will soon max out on an eight-year sentence.

It’s also home to the Christina Melton Crain Unit, the only prison in Gatesville where I’ve actually spent time (once for a couple of nights while “pulling chain” en route from a state jail to what would become my home unit and another time for a mammogram). The Alfred D. Hughes Unit is the only male facility in the area.

The Gatesville units are “real prisons.” The guys call them “rock and roll” units. You’ll see fights, you’ll see women cutting each other with razor blades. You’ll see people wheeled out on stretchers. These units are boiling hot in the summertime and freezing cold in the winter. Everything is outside, so you’re standing in the elements for commissary, pill line, and waiting to get into the chow hall.

At the privately-operated prison where I did most of my time, things were different. Those who got in a fight would spend the night in one of a handful of segregation cells, then they’d be promptly “G4’d” off the unit with a new status and a thicker disciplinary file.

Everything at Lockhart, my home unit near Austin, was indoors and temperature-controlled, so it was almost reminiscent of a large high school. There were murals on the walls that inmates painted. It was more common, in my experience, to see “offenders” holding hands in the hallways than swinging punches at each other.

I was in the faith-based dorm where there were actually Bible verses painted on the walls. We had a sound system and could play DVDs on Friday nights and listen to worship music between classes. We got our trays from the chow hall and took them back to the dayroom where we sat with groups of friends to eat.

I don’t recall much racial segregation. There just isn’t space for that. You’re stuck with the 49 other people in your dorm and it’s very likely over time that you’ll be housed with someone who doesn’t look like you. I’d been told that “bunkies” are selected by similarities in weight and age, so someone isn’t given an advantage in case of a fight breaking out in a small cell where there are no cameras. I had five bunkies during my time at Lockhart and was neither close in age or weight to any of them.

One such bunkie decided we needed our own personal plunger because the toilet frequently overflowed. Sometimes when it overflowed the doors were locked and we were left to our own devices trying to salvage toilet paper and books from getting flooded.

When an officer came by asking who had the plunger, everyone just looked the other way and said they didn’t know.

Everyone knew where that plunger was. It was in my cell.

Terrified I was going to catch a case for stealing government property or possessing contraband, I waited until the officer was gone and the doors were open, retrieved the plunger from cell 110 and marched it to the shower area, waving it around for the cameras to see. During the next count time, I told someone who was friendly with the officer that it was in the shower area.

I didn’t make any new friends that day. I deserved a proper beating for snitching on my cellie, and on a “real unit,” there’s no doubt I would have gotten just that. Sometimes you learn by making mistakes.

I’ve been hesitant to tell the “why” part of my incarceration story to my Lioness friends. They did a lot more time than I did. They served on rock and roll units. They have stories that are absolutely terrifying and put my little plunger incident to shame.

My experience inside prison might seem unfair to some. I was blessed at every turn. I got a relatively short sentence for a horrific crime that harmed a lot of people. I made my second parole. I worked for the chaplain and in the Major’s Complex.

I didn’t get raped or beaten. I never spent a night in solitary confinement.

I went home a better person than I was when I went in. I don’t know how rare that is, but that’s my story.

I decided to use those blessings to help others who weren’t so fortunate. There are people still behind those walls with longer sentences than mine who are much better people than I will ever be, doing time for crimes that should have had less severe consequences than mine.

The system isn’t fair. That’s well-established, but what we don’t often talk about is what we’re going to do about it.

When I set out to write this story, I asked an incarcerated male friend for guidance.

“What’s the most interesting story I’ve told you about Lockhart?” I asked.

Without hesitation, he said, “The hand sanitizer story.”

Within days of arriving at Lockhart, I was out on the rec yard, taking it all in. Every rec yard is different. This one had a “track” of gravel that I liked to walk around. There was a sand volleyball court, a couple of basketball hoops, and an area where the girls from the dog-training program walked their pups. Not quite a city park, but not bad at all. There were girls doing zumba classes while a boombox played hits from the ‘80s. It felt surreal, like a scene from a movie.

How did I get here?

I was a lone wolf. I’d just arrived at this unit. My bunkie at the time was a disabled older lady who used a walker to get around and had difficulty getting her meal trays and taking showers. Of course, we were strictly prohibited from providing assistance to another inmate.

A woman about my age named Eva who had been locked up for 18 years on a murder charge befriended me. I told her I was there for intoxication manslaughter. It wasn’t something I shared often. There’s a lot of shame in a charge like that, but she was open with me, so I trusted her. She introduced me to her friends, and I slowly began to trust them too.

They knew I was an alcoholic and that I wanted to start 12-step recovery meetings in our dorm. We were on COVID-19 restrictions at the time, so volunteers weren’t coming in for meetings or church services. We had no visitation.

When we went in from rec that day we were immediately racked up and told that all our cells would be searched. Rumors began to spread that someone had stolen a large pump dispenser of hand sanitizer from the rec yard.

When they finally let us out for chow on the night of the hand sanitizer incident, I sat down with Eva and her friends to eat.

Lockhart is a cell block-style prison and the doors “pop” open roughly every hour between about 4 a.m. and 10 p.m. If you want out for chow or class or to take a shower, you come out with all your belongings when the doors are released, because they’re going to be closed and locked about five minutes later. You’re going to be stuck either inside the cell or out in the dayroom until the doors open again.

When the doors popped at 7 p.m. that night, I was out in the dayroom. I’d eaten dinner and was ready to go in for the night. I told Eva and my new friends I was headed “to the house” to read a little and go to bed. It had been a weird day and our cells had been turned completely upside down as the guards searched for the elusive hand sanitizer bandit.

“You’re going in so early,” my new friends said to me.

“Eh, I’m just going to make a little hand-sanitizer nightcap and call it a day,” I told them.

I think a few of those women actually fell out of their chairs.

I’m not sure why I said this. I wanted to make them laugh, for sure. I wanted them to like me. Maybe I wanted to give myself a little street cred that I belonged among them. I needed them to know that I didn’t think I was better than them (a stigma I fought throughout my incarceration).

“You know what I liked best about the sanitizer cocktail story?” my male incarcerated friend wrote to me. “The event itself was funny and weird and very prisony. But it was the way you used the situation to endear yourself to your peers that said something to me about who you are. The way you made fun of yourself while also exploring the feelings of guilt you had — that took an anecdote and made it powerful to me.”

That pretty much sums up my prison experience. Finding a silver lining. Taking the fact that I’d killed a man with my bare hands, a Nissan Altima, and a plastic bottle of Smirnoff, and turning that into something that might be helpful to others, especially women who suffer from alcoholism.

I got better. I got healed. The obsession to drink alcohol was removed from me, and I wanted to share that message of hope with my peers, even if it required making fun of myself.

But then there’s that sinking feeling. Do I even have the right to laugh?

I had another blessing in my back pocket. When I made amends to the family I had harmed — my victims — they showed me kindness and forgiveness. They encouraged me to tell my story and help others.

People feel very strongly about drunk drivers. For years I felt like I was not allowed to laugh or experience joy because I’d taken those things from someone else. When you’ve done something bad, especially something bad that hurt a lot of people, there’s a massive internal struggle in trying to figure out how to be of service to others while never speaking of the bad thing you did.

How do I show gratitude and humility with every word that comes out of my mouth? It’s impossible. Some days I think I’ll die trying.

Some days I just try to live.

One of my Lioness friends said on our trip to Gatesville that she spent so much time in that little prison town, she had to check herself when people ask her where she’s from.

A prison is never really a home. Although commonly referred to as such, the cell is not your house. We all hold on to a shred of hope that someday we’ll be back “in the world” with a door we can open and shut at our own free will, that we’ll be able to use the restroom in private, and that we’ll be able to sleep on a soft mattress with a pillow that isn’t made of a T-shirt and a towel.

Some would argue that your prison “friends” aren’t really your friends, but I’ve seen that disproved. In fact, we’re closer than friends. We’re family.

When the Lioness girls gathered for dinner at a barbecue restaurant in Gatesville the night of the vigil, we shared a meal, much like we had back in the dayroom years prior. We didn’t have to use a blow dryer and a cardboard box to make the fried food this time. The laughter and interest in each other’s lives was genuine, the same as it was when we were incarcerated.

Prison is punishment, and I deserved to suffer the consequences for what I did. Sometimes I hear people say, “She has to live with what she did. That’s punishment enough.”

For me, it wasn’t punishment enough to live with the shame. I needed to go to prison and be disconnected from my loved ones, my career, and my material possessions. I needed to learn that I couldn’t manipulate my way out of this one. I needed to have consequences in order to change.

I got the gift of desperation. I made friends with people I never would have met under other circumstances. I don’t think prison saved my life, but I know it taught me a lot about the kind of person I want to be.

And I don’t think I’ll ever characterize it as a good experience, but maybe it’s something I had to go through to get to where I am today. We change when we’re uncomfortable, and I was certainly uncomfortable.

I didn’t need a lot of time to recognize that I’d have a healthy, productive, meaningful life if I was willing to change. With that knowledge and that preparation, I am equipped today to be of service to the men and women I left behind.

I’m committed to continuing that fight until they all come home safely.

No Comments