To read Chapter Two, click here

Kimba

Ground shaking heavy-metal, the smell of gasoline fumes and spilled beer mixed with the coppery taste of blood. Then, the nauseating stimuli swirled together in a noxious cloud and disseminated into the retreating dreamscape of Kimba’s mind.

He lay still with his eyes closed. His consciousness pushed the visual and auditory images back into the dismal recesses until there was nothing but a shadow of melancholia left on his spirit. He woke with this shadow each morning and carried it with him throughout the day until he returned to his subconscious purgatory each night. Kimba opened his eyes and blinked once. He stepped directly from a nightmare into a dream, this new surreal reality that was his. Even after five full months, he still struggled with the transition back into the land of the wakeful living after so many years of waking in the land of the walking dead. Before he rose each day, Kimba took stock of what was real and what was not, who he was and who he would never be. He carefully catalogued and compartmentalized the simple components of which his belief structure was constructed. This prevented moments of hesitation or confusion as he moved tentatively through each day that bombarded him with choices and information. His new reality was a world both hostile and foreign, a brightly colored place where he felt in constant danger of being swept away by a colossal wave of ambiguity.

He sat up in bed – a full-sized mattress and box spring that lay directly on the floor of a spacious living room. He swung his feet out and took a moment to observe the strange sensation of carpeting on the soles of his bare feet. Wearing only a pair of black sweat-pants cut off below the knees, he slowly stood, made the bed, and went to the enormous bank of windows that overlooked the valley to the south. His 38 year-old joints popped and creaked like those of a boxer past his prime; they seemed to take a moment to warm up to the idea of forward locomotion.

Kimba stood in the remodeled loft of the oldest building in Vermilion, a now defunct theater called the Magic Lantern. A heavy early-morning fog obscured the valley and winding Snake River – his view limited to the empty two-acre gravel parking lot below. He looked out the wall of windows – each piece of glass a square foot in size, set in a steel frame 8 feet tall and half the width of a full sized movie screen. The window had been installed over a hundred years ago to allow natural light into the attic – a space with roughly the same area as the stage below. In those days, according to his father, the attic had been used to store props and costumes for the numerous set changes always involved in the production of operas or plays. The attic had been remodeled completely and turned into living quarters before Kimba’s father went to Vietnam in 1967. Kimba had just turned 2.

Kimba went to the bathroom and used the toilet. He still marveled at the comforts of a normal bathroom – a plastic seat that lifted or the ability to adjust the temperature of the sink or shower water with two separate knobs. While he washed his hands, Kimba wondered how long it would take for the novelty to wear off and for him to feel as though he had at last rejoined western civilization.

Kimba returned to the living room and went to the only other piece of furniture besides the bed – a forty year-old Magnavox stereo, one of the last models to be made out of real wood. Some of the fifty or so albums stacked next to it had sat and gathered dust for over twenty years. Others that had belonged to his long-dead mother had been abandoned for much longer. He thumbed through the stack-past the Scorpions and Judas Priest – and on a whim, selected Giuseppe Verdi’s La Traviata, one of his mother’s favorites. For five months now, Kimba had been trying to flush himself out of a long, deep groove that separated him from the rest of the world. He set the stylus on the vinyl and the sound of classical horns and strings filled the loft. Kimba frowned and let the music wash over him.

Kimba went to the small kitchenette and drank two 16 ounce glasses of water. Then, standing barefoot on the linoleum, he swept his mid-back-length black hair into a ponytail and got on the floor. He extended his body face down with hands apart at shoulder width. With his back straight, he looked forward, inhaled through his nose then lowered his chest to within an inch of the floor. He exhaled through his mouth and pushed himself back up into the starting position to complete one push-up. He performed 29 more repetitions exactly like the first, slowly and methodically, always mindful of his form. Finished, he got up and walked the circumference of the living room – an activity that took 65 seconds, having timed it several times with his watch. Back at his starting point – the floor of the kitchenette – he did 30 more push-ups like the first set. By the time Kimba had taken nine trips around the living room, he had done 300 push-ups in about the time it takes to make a pot of coffee – the same time it took to do 300 push-ups several mornings of the week for the past two decades.

Kimba opened the refrigerator. An astonishing assortment of choices awaited him – all micro-choices to be made that stemmed from a master selection that he had created at the grocery store two days before. When he looked in the fridge he saw himself at the store, saw people staring open-mouthed at him as though his spaceship had just landed in the Safeway parking lot. Women instinctively held their children closer to them when he walked by, and men regarded him with both apprehension and outright contempt.

Once, several weeks ago, a man in his early twenties wearing a cheap suit bumped into him in the canned goods aisle. The man and a similarly dressed colleague had been walking without watching where they were going. The two were prosecutors or frugal defense attorneys that had just come from the courthouse and were holding an animated discussion about a case – a case too important to warrant more than a sideways glance of annoyance in Kimba’s direction.

Kimba was not a violent man, but for a time, he had been conditioned to react violently to those who challenged his honor or personal space. The latter had clearly been violated, but Kimba had learned to temper his explosive out-of-body experiences and was able to confront adversity with the resolute calm of a Japanese tea gardener. The expression on the lawyer’s face told Kimba

that he had been the one standing in the wrong place, a spot in front of the Del Monte pineapple chunks. Instead of grabbing one of the cans and crushing the man’s skull with it, Kimba implemented a shade-tree variety Zen technique he had formulated himself; he fastened himself to the moment – the abstract unit of time and reality that existed in his own psyche and centered himself there. His higher brain remained occupied while his knuckle-dragging lower brain slumbered. He remained suspended there until the external event that took place in real time passed, and the rude attorney was gone. Kimba was highly vulnerable during these episodes, but could find no other means to move about in this world where he was nothing more than an exotic animal that stood outside the realm of common courtesy.

For Kimba, public places were littered with social landmines. Many of the subtleties involved in the human interaction that he carefully studied left him scratching his head. In his world, name-calling was serious business. Each word had a specific connotation designed to illicit an exact response – a form of tribal test to establish pecking orders and to keep the pool of alpha-males from being tainted by weaker types. To watch a young woman call her boyfriend a bitch loudly in the laundromat had initially caused Kimba to wince while he waited for lightning to strike, only to feel like a member of another species when the boyfriend grabbed her by the waist and began to tickle her while she shrieked with laughter.

This broad expanse of acceptable ways to express thoughts and opinions were not completely foreign to Kimba; he had been one of these people once, long ago. He would learn how to fold harsh words into lighthearted banter again and to understand the complex nuances involved in flirting with the girl at the checkout counter. He would even learn how to smile when a disrespectful punk bumped into him without a word of apology – a punk who in Kimba’s world would be sodomized both orally and anally his first day there, then perhaps forced to wear a dress and make-up made out of M&Ms for the rest of his miserable stay.

Kimba settled on a couple of good slugs off a bottle of Ocean Spray cranberry juice. He savored the mildly tart liquid as it flowed over his taste buds, noting how different parts of his tongue detected the sweet and sour elements separately. He put the bottle back then returned to the wide-open space of the loft. He consulted the watch that lay on an old wooden produce box turned upside down that served as an expedient nightstand. Also on the box sat a half-burned candle that he read with at night, a well-worn copy of Shantaram, and an ancient American Indian bracelet made of badly tarnished silver and studded with turquoise. Once he noted the time, Kimba lay on the carpet and performed ten sets of 100 crunches with a 60 second break in between each set.

Kimba harbored no resentment towards the citizens of Vermilion that treated him with open antipathy; only he knew who he was now, the good he was capable of, and his ability to become a well balanced, functioning member of this town. It was also only he who knew the open, festering wound in his soul that never healed and oozed into his restful sleep, poisoning his dreams almost every night. That punishment eclipsed any that could ever be imposed by a Superior Court Judge or an over-zealous Department of Corrections employee. The people of Vermilion remembered only that he had taken the lives of innocent victims – including those of women and children – leaving pieces of their dismembered corpses lying around like the unwanted parts of the animal tossed onto the floor of the butcher shop.

It had taken the furtive glances and wide open-stares of these people directed at him for Kimba to finally understand the isolation his father had felt for the remainder of his life after returning home from Vietnam. Kimba recalled those times when his father would drink himself into a sloppy stupor while he ran the projectors – sometimes too drunk to change the reels. At other times he would lapse into somber moods for days at a time, perhaps beating Kimba or his mother senseless, or with luck, completely ignoring them both. His mother would say that these periods of depression were caused by chemicals used in Vietnam to kill vegetation that had left his father sterile – a frank admission to a ten-year old boy, but perhaps the only explanation simple enough for a boy that age bewildered by his father to understand. Still, Agent Orange had not caused the social disease that was more threatening to the locals than the hopeless drunk who was running the old theater into the ground – they had come to look at him as though he were a predator that mingled among them, like grazing zebras that kept a wary eye on a well-fed lion snoozing in the shade nearby.

Once Kimba had finished with his workout, he put on some expensive but well broken-in running shoes, a T-shirt and a gray pull-over sweatshirt. He placed his keys, cash and cell-phone into a fanny-pack and carried it in his hand. He had tried to wear it in the traditional way, but it felt cumbersome and foreign to him, like a useless appendage. He barely knew how to use the phone and it seldom rang, but Kimba knew this was an integral part of being a modern-day citizen in the new millennium.

Kimba left the loft from a heavy steel fire door that had been recently installed for security. He trotted down a flight of enclosed steps and paused at the bottom. The scene still surprised him upon seeing it every morning; the theater was gone. Seats had been torn up and replaced with a dance floor with a full bar and lounge on the north end of the auditorium-sized space. Each morning Kimba stood here in the gloom and reflected upon the relative simplicity of those days gone past with his own brand of nostalgia – a bittersweet amalgam of his father’s capricious, violent outbursts combined in a bizarre collage of bits and pieces of movies burned into his brain. He had watched and listened to them over and over, night after night. When he had arrived at the theater five months ago after a 22 year absence, only one area of the building remained that even provided a clue that movies had ever been shown here at all. The small concrete projection room located behind the balcony seating above where the bar and lounge had been added during the last remodel completed in September of 1998. Kimba had gone up there only once, feeling a mild, detached sentimentality upon seeing that the place was now used to store banquet tables and other restaurant equipment. The movie screen that once taken up the entire south wall of the huge auditorium was long gone, having been sold or stolen during the theater’s period of vacancy after the death of his father. Kimba’s skills as a projectionist or 38 year-old usher would not be needed at the Magic Lantern anytime soon.

Kimba cut back and moved southward through a dark hallway towards the rear exit. According to his father, this part of the building had once been the top of a stone wall that surrounded an area dug into the earth to store munitions. The building had been the original armory when Fort Vermilion was built, completed in October of 1848. General Gerald Vermilion had selected this spot for the fort because it overlooked a section of the Snake River that settlers breaking away from the Oregon Trail had chosen to cross. The current on the west side of the bend ran slow, the river shallow and wide. Because immigrants would sometimes spend a few days here to rest and water their animals before continuing west, local Nez Perce and Cayuse indians – already restless and hostile – turned this part of the river into one of their most productive ambush points. After several surviving members of the immigrant parties limped into Seattle relating first hand accounts of gruesome scalpings, the brutal rape and even murder of their people, the Army tasked General Vermilion with selecting a spot to build the fort. The Whitman Massacre on November 29th, 1847, helped cut through typical government red-tape like a hunting knife honed to a razors edge.

Out in the parking lot, Kimba set off in a slow jog along the east wall of the building, across the empty front parking lot, and onto a sleepy, early Saturday morning Main Street. He glanced at the Bank of America sign across the street; it was 7:21 and 47°.

The morning sun appeared only in brief glimpses at first as it burned slowly but steadily through stubborn fog. Kimba jogged west on Main along the tiny family-owned shops – still dark and uninhabited beyond the plate-glass windows. He cut diagonally across the empty street, past the courthouse – perhaps Vermilion’s most modern building with new brick, bronze window frames and tinted glass – and rounded the three-way stop where Main, Dora and Highway 469 intersected. The sidewalk curved to the right, then ended abruptly and turned into a gravel strip that ran north along the highway. With the end of the sidewalk came the end of the town, a jagged edge of broken concrete separated Vermilion from vast wilderness – the terrain on both sides of the highway instantly transformed into dense forest.

Within one mile of Kimba’s starting point behind the Magic Lantern, his body settled into a familiar rhythm. His heart, muscles, lungs and joints now all operated together as a single entity; only his mind remained detached from the cohesive unit, free to roam at will. Sometimes he ran along a sandy beach. Waves with mist and foam blowing off their tips would crash to the shore, then return to the sea with a long, serpentine hiss. On some days, the same beach would have been taken over by women that languished on over-sized beach towels and wore French-cut bikinis – like a section of coastline over-run with California seals. At other times Kimba traversed fragrant vineyards during the heat of summer, smelling the sweet aroma of grapes while the air shimmered above the fields of vines laden with the tiny, ripened fruit. When he was especially focused, he was able to replay old movies almost scene-for-scene, including dialogue, or rebuild an automatic transmission down to the last minute ball-bearing with the smell of solvent and burnt Dextron II transmission fluid in his nose.

The sun now made a full showing, only patches of fog in deep valleys and ravines remained. Kimba left the highway and increasing morning traffic and took his normal route – a pothole riddled gravel road called Lariat. He followed the road as it made a wide arc to the left until a glint of metal caught his eye. A small group of mobile homes and a single brown house appeared as the road curved back to the east, all clustered together and huddled around a dead lawn scattered with loose garbage. Normally on Kimba’s early morning sojourns through this area, signs of life were scarce, but today there was a flurry of

activity.

The brown house had been vacant since Kimba’s return to Vermilion, but today people were moving in. A white chevy Tahoe gleamed next to an older maroon Honda Accord – both vehicles parked well to the side to make way for the full-sized green and yellow Mayflower moving van parked along the front edge of the lawn. The van had parked next to the giant juniper tree, bullying it‘s stout lower branches roughly to the side. Two men barely awake had a long, polished oaken dresser between them and shuffled down the ramp behind the truck. A third man stood by, watching. The man on the ground was in his early forties, with brown hair cropped short, and a graying goatee that made him look a man that refused to accept the fate that they both shared; were getting old. Without conscious effort, Kimba quickly sized up the man as a physical opponent. He noted the thickness of his neck and powerful shoulders, but also how they lacked definition; he had at one time been a man who maintained a certain level of physical fitness, then one day – for whatever reason – had thrown the towel.

The man picked up Kimba’s movement when he came into his peripheral vision. He turned and fixed him with icy-blue eyes which allowed another piece of the puzzle to slip into place; the man was a cop. There was no mistaking the certain brand of contempt that law enforcement people from every sector held for Kimba and his kind; he looked away quickly, an instinctive reaction to prevent himself from being recognized before he could become the recognizer should the man prove to be an enemy from the past.

Kimba trotted past the van, the man with the goatee and the sleepy movers. He was five or six steps away from being out of view when an attractive woman in her late thirties stepped out through the sliding-glass door and onto the porch.

“Honey, could you come in here, please?” she said to the man with the goatee. “I think we should move the entertainment center to the other wall.”

The woman wore an oversized T-shirt and loose-fitting jeans. Her shoulder-length, dishwater-blonde hair had deep dark roots and was pulled up behind her head in a loose ponytail. Her eyes were big and dark behind simple gold-rimmed glasses that sat on a delicate nose generously sprinkled with freckles – her skin pale and unblemished, but cheeks flushed with exertion.

Kimba replayed the woman‘s voice over and over in his mind. He tried to access the unique lilt filed somewhere in his vault of memory. Just as he slipped past the front of the house, the woman crossed her arms loosely in front of her, and leaned forward slightly as she awaited a response from the man with the goatee – a mild idiosyncrasy that revealed her identity to Kimba just as he stepped out of view – a recollection so sudden and powerful, it caused a brief anomaly in his step. He was now well past the house, and sure the woman had not seen him, but his body betrayed him; despite his efforts to control his reaction, Kimba’s heart began to pound furiously and his mouth dried up. Emotions that he had not experienced in years welled up and eddied in his mind. He struggled to complete the ritualistic beginnings of his morning, since his entire existence was comprised of small, well-plotted events throughout the day that were linked to each other in logical succession. The breakdown of just one of these events threatened to throw him into complete and total chaos.

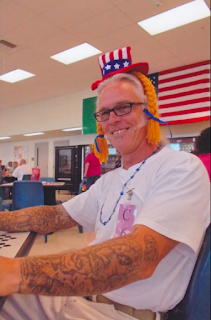

Anthony Engles 832039

* for more information click here

1 Comment

Vargr Wolfsson

August 4, 2019 at 7:27 amHere it is! It's nice to see it in something other than handwriting. I don't know how to access the rest of the story, but I'm here supporting it anyways. I'll have my sister acting right in no time (fingers crossed)