My mommy stayed quiet, a stabbing in my chest, as Mama Pera, my father’s mother, matter-of-factly suggested having my ears surgically pinned back—a procedure I would learn had the name otoplasty. I could feel my large, outstretched ears get hot with shame as I hid listening on the steps to our three-flat on Chicago’s Southside. I was six.

Mama Pera spoke with God-like authority and would get faint when anyone dared to question her. Mama Pera knew things; God told her things. End of conversation. She was never wrong and if she was, she would discuss it directly with God when she arrived in heaven. She had opinions about everyone and everything.

My mother, her nemesis, was everything she wasn’t. She was kind and gentle, patient and understanding, loving and caring. She was raised in rural Mexico in a town so small the bank and bakery shared the same building. Her father left the family of eight when she was only 10, forcing her to grow up too fast and understand desperation the way no child should. She doesn’t speak about those long days with empty stomachs; like many of her generation she holds her cards close and suffers in silence.

We were a Mexican family in a Dave Matthews slice of suburbia. My sister and I were the only kids at our school with a hint of melatonin and an accent. I hated being Mexican and would often lie and claim a false Italian heritage. But one look at my Ricky Ricardo dad and Mestizo mom and the jig was up, as they say. I oozed my Latino roots. My bag lunch and sandwiches made of refried beans, scrambled eggs, avocados, and jalapeno slices smelled like a favela against the simple bologna and cheese of my classmates.

I crept back to the bedroom I shared with my older sister and dropped to my knees to pray:

“Please God, I love you. I am sorry for lying and hitting my sister and kicking the dog and yelling at my mami and for thinking bad things about my abuelita. Please make my ears small and normal. Thank you God. See you tomorrow.”

My older sister, still in pigtails and braces, turned over in her bed and grunted, “Shut up, you’re fine, they match your head.” I felt better, but still grabbed the large rubber band I kept next to my bed, wrapped it over my head and ears and tried to sleep.

My ears didn’t stick out like two open car doors my whole life. I was a cute baby. In kindergarten, seemingly from a fairy tale curse, they simply popped off the side of my face. The bullies were tickled pink. “Look at Dumbo. Here comes Dumbo.” Making matters worse, my ears would burn bright red with shame even as I tried to pretend the teasing didn’t hurt. I never told them to stop or told a teacher: I could not put those feelings into words and simply stuffed them deep into secret chambers. I only know I felt sad and wanted to cry, but knew that would only make matters worse, so I would bite my lip and run home to tie on my rubber band.

Before that night my mother was my rock. She thought I was perfect as-is. She loved to comb my hair and told me I looked like Superman or Elvis. She would proudly show off my school pictures to anyone who visited, and they were always framed and mounted on our living room walls. But she didn’t say anything when Mama Pera recommended I go under the knife to fix my elephant boy issues. She agreed. Silent consent. I had no one.

I blamed my father’s side of the family. My father’s go-to move was to pull me by the ear to get my attention. I was sure it was all that pulling that caused my deformity. Also, my grandfather, Don Ignacio, my dad’s dad, had huge pig ears. Don Ignacio told me I should be proud of my ears; they were a family legacy and made fun of my father’s tiny Ewok ears — the ears I desperately wished I was born with. In one photo, my granddad’s ears resembled giant jug handles. It was clear I would NOT grow into these Yoda-like appendages.

The ears wouldn’t have been such an issue if I had other things going for me, but I wasn’t a natural athlete (unless you count tree climbing) or student. I was lanky and weird, making playing sports humiliating and disappointing. I wore braces for four years and needed glasses young. I even had a Forrest Gump-like knee brace for most of third grade. I really was an outcast, like Dumbo.

At this point, I must jump ahead.

It is now my sophomore year in high school and my Mama Pera is turning 90. We’re Mexican, so you know we’re going to throw a loud, obnoxious colorful party with lots of beer, music, food, and a piñata. (God forbid we celebrate anything without a piñata). Mexicans love their music and dancing is ingrained in us kids along with soccer and the Bible. But I’m anti-Mexican. I hide my Mexicanness. I don’t play soccer, nor do I listen to badda-bing, badda-bing salsa music, and I have never learned to dance salsa, merengue, tropical, cumbia, none of them. Much to my mother’s dismay. My whole life she loved to dance. Every morning and when I returned from school the music would be blaring and she would be sashaying as she was cleaning or cooking. She used to try and rope me in to join her, beg me to dance with her, but eventually she got tired of my rebuffing and I’d-rather-die side-eye or eye roll. By the time I was 10 she learned to leave me alone, but that didn’t stop her from throwing herself all over the house, singing along to her favorite bands’ classics of her youth.

Mexicans have many unique traditions. Some I kinda like, like the huge family gatherings. Others I can live without, like the one at weddings or birthdays of older patriarchs where the party guests are supposed to pin some money on the guest of honor’s clothes and then dance for a few minutes with them. (At my sister’s wedding, she danced for almost 45 minutes collecting over $1,000 from half of the 300 guests in attendance). Now, at the party, I am being pushed to go dance with Mama Pera. It’s tradition, they insist. Here’s $20 to pin to her dress. I don’t know how to dance. I am not a big fan of this witch . . . but familial pressure and guilt are powerful forces.

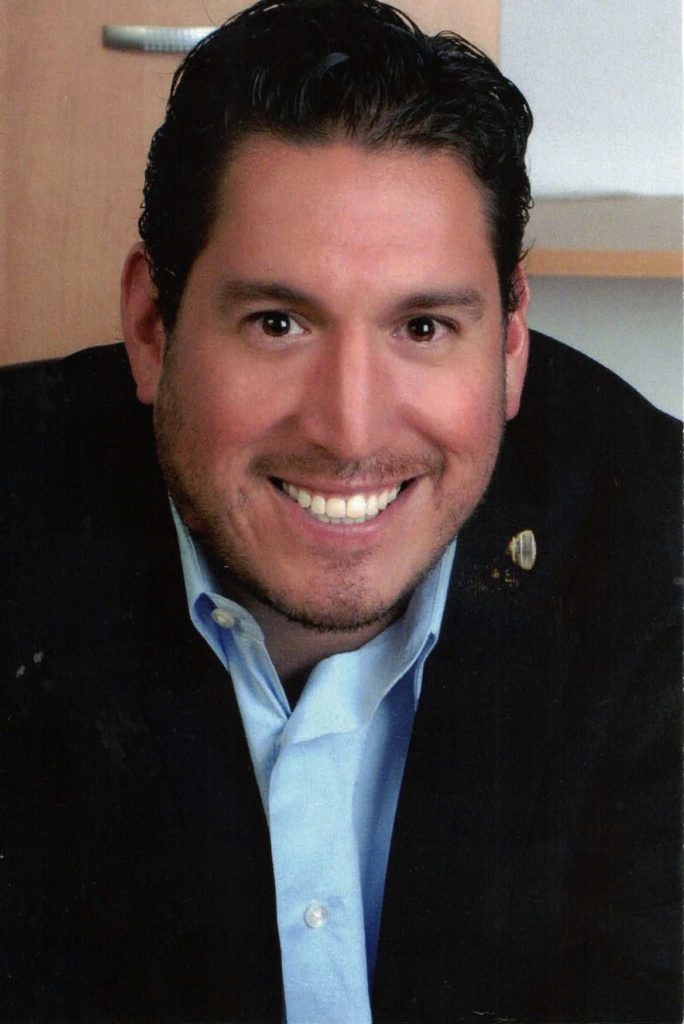

At 90, she’s not exactly cutting a rug, so I pin the money on her yellow frilly dress and begin to walk away while holding her waist. She forgets things now. She can’t live alone. She’s not allowed to cook. She’s shrunk. She’s fragile in my arms. At 6’2” and a fit 180, I tower over her. She looks at me for a long second and exclaims, “Nacho, you’re so handsome now. Look at your ears! They’re beautiful.” Her smile is so genuine, so pure, my heart melts and just like that I forgive her for everything she’s ever said. She gently touches my right ear as if she can’t believe it. I can’t help myself and blurt out, “I didn’t even need the operation.” She’s confused. Hurt. I regret saying it the moment it left my lips.

See, sometime around eighth grade my curse was broken, and my ears simply snapped back into place next to my head, eventually everything else started to align. Braces off. Contact lenses. Grades. Popularity. No more bullies.

Mama Pera is lucid again. She straightens up, looks me straight in the eyes and explains how she just wanted the best for me, but my mom would have nothing doing. She forbade her from ever speaking of it again, turning from the dishes with a large butcher knife in her hand and warning her if, God forbid, she ever hears about it from anyone else. Before I can respond I get a tap on the shoulder; it’s my cousin Eddie Spaghetti, it’s his turn to dance with Abuelita.

Cut back five years.

Life has been difficult at home. My sister got pregnant young and had to drop out of school. My father had grown distant and hard with my mother and us kids. I was rebelling, hormones raging, from all forms of authority. I had cursed out my mother in a fit of rage, even raising my hand to slap her — all this for asking me to get off the phone to join the family for dinner. (It hurts me to write that sentence today). I refused to speak to her and the few times we did it would immediately turn ugly and end up with me storming out of the house for hours or days on end. I would later learn she would pace the house worrying, crying as she walked by my empty room.

Back to the party.

I walk over to my mother who is chatting with her sisters at a large table. I hold out my hand and ask her if she still wants to teach me to dance. I wonder if I am saying the right words in Spanish as she looks lost and bewildered. Then. Then a smile so large and so bright I will remember it forever spreads across her face.

“I have to go dance with my son,” she proudly tells her sisters and almost jumps into my arms. I lead us to a corner, too embarrassed to join the pros center floor. She walks me through the four basic box steps, she shows me how to add a little flourish and panache or “sabor” (flavor), as she liked to call it. I stepped on her toes; she never complained. I was awkward and out of step; she never stopped smiling. We laughed so hard and were so lost in our little bubble that we missed the cake and the piñata.

That was our first and last dance.

Her love has never faltered even as it was tested under the harsh light of criminal allegations, a conviction, and a lengthy sentence. She never stopped dancing with me, and I regret that I didn’t give her more reasons to dance. One day, I pray, when I finally leave this dismal crypt, I will dance with my mother again.

In this world or the next.

No Comments