By Steve Bartholomew

Big Chuck plucked with great deliberation his final wooden tile and, placing it alongside the six others he‘d laid on the board, tacked the word “eulogize” onto the E of his opponent’s previous play. Triple word plus a Scrabble. He adjusted meticulously the alignment of letters, the fine-threaded movements of his hands belying their coarseness and sheer size. His opponent laid with solemn affect one palm on the dictionary. Big Chuck shrugged his indifference toward the challenge bluff and stood slowly from the steel table, his hinges relucting at the business of articulating. without speaking he turned and walked toward the bathroom on the other side of the crowded dayroom. His equivalent of a mic drop.

Staring at the white tiles above the urinal, he registered dimly the sibilant whir of the gear-driven actuator drawing open the dayroom slider. A figure in blue moving across the bathroom entrance at his periphery. Probably that gung ho bastard Hesselman, he thought, making an extra tier check between the hourly. Going after the big bust, maybe to interrupt another crappy tattoo. Taking a bite outta crime, that one.

He crossed the bathroom and stood facing a porcelain sink. Glancing at the grizzled mug in the dented mirror, he hit the hot water button and tapped out a dollop of hand soap. Nothing like scuffed up stainless to take off ten years and twenty pounds, ne mused, reaching for the paper towel hanging from a nearby dispenser.

From the dayroom came the clang of steel striking concrete. An enormous baritone note ripping the air like a thunderclap, reverberating through the box-shaped pod.

An expert machinist and fabricator, Big Chuck had worked intimately with metal for four decades. He knew maintenance hadn’t entered the pod, and could assort this sound only as being in no way constructive. The dayroom din had gone silent save for one voice, proclaiming fury in a tongue unknown to him. A metallic tolling punctuated the shouting, timeless and wavering in intensity. The sound of a bell detonating bright as a brass hammer, then a knell ringing dull like a meat-filled gong.

He peered around the dividing wall. A guard lay face down on the floor, his feet splayed out in Big Chuck’s direction. One booted foot jerked and scatted, spastic. Plastered across the heel a cartoon ghost of bluish gum. A Somali prisoner stood over the guard, wielding overhead a gray metal disc. Big Chuck recognized it as a buttplate. Made from quarter inch mild steel, a buttplate derives its name from its function: a one foot diameter plate with a two inch rim, designed to support one human butt and usually attached to a cell desk. Must have been bad welds, Chuck thought.

The fallen guard began bleating and gibbering. Appeals divested of language and intoned to god and man alike.

Somalia screamed, “Allahu Akbar” and swung the buttplate down, striking the guard’s head.

Every prisoner in the dayroom had abandoned their tablegames and conversations to line up against the far wall, adding as much distance as possible between themselves and the spectacle unfolding. A Rorschach halo of blood expanded darkly on the waxed concrete floor.

Big Chuck pointed at the guard. “Who is that?” He was asking anyone, so no one answered.

“Who. The Fuck. Is that,” he demanded, making eye contact with his Scrabble opponent.

“It’s Wally.”

Walychtowski was one of a vanishing subset of guards who treated prisoners like humans, an outlook in defiance of his cohort. Known simply as Wally, he insisted on hiring for his work crew those prisoners deemed too risky by other staff. He believed anyone willing to work ought to be given the opportunity to prove, and support, themselves. In the entire compound Wally provided the lone means for an income to gang members and former knuckleheads with a history of violence. He treated prisoners with respect unless they elicited otherwise.

Big Chuck stepped out from the bathroom and lumbered toward the assailant, eyeing the steel bludgeon held aloft by one dark spindled arm. His knowledge of the Somali included a difficult personality and impossible name. Nor did he want to learn more. He brought up his blacksmith-like forearms to protect his head, a boxer’s defensive stance. Long as he don’t bounce that thing off my dome, Chuck thought, I can soak up a body shot from this scrawny maggot, easy. One, that’s all he gets. Let me catch hold of that charcoal twig of an arm and he don‘t stand a fart’s chance in a hurricane.

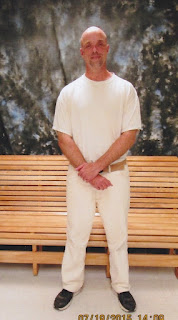

Big Chuck‘s moniker wasn‘t one he‘d have chosen himself, but he cou1dn’t deny that it fit better than state issue shirts. He’d been a power lifter his entire adult life. Even now, a few months past his 60th birthday, his six foot three frame tipped the scales at 295 solid pounds, give or take a burrito. In prison, a 500 pound bench press is legendary. Chuck‘s had been well north of that until physics and biology had come collecting on his joints a few years back, making him lighten up his lifts. A little.

Steeling himself for impact, he advanced steadily. Watch the eyes, thay’ll telegraph the swing. Obsidian shards burning, bulging like burial mounds, cast in shapes of murder. Chuck took another step, flanking his opponent. 5omalia‘s eyes cut side to side, revealing uncertainty as it fused with rage, an alloy of hesitation. Big Chuck tucked his chin and forged ahead inch by inch, his face giving nothing.

He gauged the tensile strength of Somalia’s will, estimating the shear point. His focus tapered, indexing the way in. Hydraulic presence. Bear down without relent. Breath by breath. Be the anvil, tempered as a cold chisel. He moved within striking distance and opened his hands to grapple, wagering that he‘d quenched the other man‘s arc.

Somalia dropped the buttplate and ran to his cell, unlocked the door and went inside.

Chuck knelt in the crimson pool fanning out from beneath Wally. So much blood. Coppery reek coated the roof of his mouth. He’d done a nickel in Florida back in the late 70s and early 80s. when violence was commonplace and survival earned, not a given.

But he’d never seen up close such an emblem of gore. Wally’s scalp was rent in places like oilcloth. Skullbones peeking through pinkish and waxy, smeared. Convex here and cleaved in there. A daubing of cranberry-like jelly.

Wally’s shallow exhales blew small bubbles in the blood at his nostrils. The quick of shock.

Chuck cradled the man‘s head, elevating his airway just above the growing pool. His clothes wicking the cooling blood against his skin. He uttered softly into Wally’s torn ear what assurances he could muster. You’re okay now. Help’s on the way. They‘ll get you patched up in a jiffy. Just you hold on.

Muscles in Wally’s extremities tremored and seized, nerve impulses shortcircuiting. They should have already been here, Chuck thought, other guards, the CERT team. He turned to look at the line of gawking spectators frozen along the wall.

“Get help!” he bellowad.

One prisoner broke rank, running to the pod slider, waving and pressing the call button there.

When the CERT team stormed the dayroom, they found Big Chuck kneeling over the prone guard, covered in blood, the buttplate conspicuously nearby. Chuck holding the man’s head in both hands. The CERT sergeant began barking for him to get on the

ground, hands behind his back.

“I will,” he said quietly, “but somebody‘s got to hold him up. He’ll drown.” One of the CERT guards nodded and knelt beside Chuck, sliding gently his gloved hands into the blood, relieving the big man.

The brass quickly deduced the actual assailant. They had only to follow the trail of bloody footprints to the Somali’s cell, than ask a few audience members what had happened. Big Chuck was allowed to clean up shortly and return to his cell and the entire prison went on lockdown.

Over the following days the unit slider would open several times per hour, the lock on Chuck’s cell door popping simultaneously. Nearly every staff member on the compound stopped by to thank him personally for having saved Wally’s life. From graveyard rookies to the superintendent, they wanted to shake Big Chuck’s hand.

“I really just wanted to move past it,” Chuck told me when recounting the story. “At first, I was nervous as a Chihuahua shitting peach seeds. Criminy, here‘s the warden standing in my cell wanting to shake my hand. And going on like he wants to give me a medal. Fuck oh dear. I mean, I got no idea how to act. And then comes lieutenants. Sergeants. Tower guards, I think even cooks. Hell, I never seen half of ‘em before. I really wasn’t digging the attention. But you know I can’t exactly say that to them.”

Some were stoic, military in their bearing. Others became emotional. Each was profoundly grateful to this gigantic lifer who had saved their coworker and friend. He obliged them each, listening patiently and acknowledging graciously their praise even though his convict nature screamed, Hell no, you don’t shake hands with The Man. Again and again he insisted he’d simply done the human thing, what anybody would have done. Over the years, he‘d learned how to deal with angry lieutenants, but not one with tears in his eyes. “The doctors are certain,” the L.T. said, standing inside Chuck’a cell. “He couldn’t have survived one more blow to the head. His injuries… Chuck, you saved the man’s life.”

A week later an escort cadre arrived at Chuck’s cellfront. They said please, but he knew they weren‘t actually asking that he accompany them. He’d been expecting them at some point. They did not bother with handcuffs, despite the hard lockdown still in effect.

Inside the interrogation room, a Port Angeles Police detective asked for his version of what had happened. Two officers from Investigation & Intelligence, the secret police of prison, sat at the table. The cameras in the pod had malfunctioned that day, they told him. Luckily, most cameras in modern prisons wear khaki and ID tags. I & I already knew the details of the event, many from Somalia himself. He had confessed immediately, proudly declaring that he had laid in wait to kill Hesselman, not simply to assault him. Hesselman was the type of guard who believes people are in prison for punishment, not as punishment. Opportunistic and antagonizing, he had targeted the Somali prisoner, harassing him with petty infractions and retaliatory cell searches. Somali’s window of tolerance could admit no more bullying. He spent days levering loose the buttplate. In the heat of vengeance he mistook Wally for Hesselman, confusing one middle-aged white guard for another.

Big Chuck told them he’d simply seen Wally in severe distress and helped him. His account did not include having seen Somali assault Wally, or his own intervention. But they knew Chuck’s full role in the event from the pile of witness statements already submitted. When the detective asked him to detail his involvement he said his sole focus was on helping Wally. They asked if he’d be willing to testify.

“All due respect, Boss” he said, “I just did what I thought was right, in the moment. Anything after that is your business, not mine. I really don’t know anything else.”

They escorted him back to his cell. A few days later another escort appeared at his celldoor.

The lieutenant greeted Chuck at the entrance to his office. Chuck declined the cup of coffee offered. The L.T. asked him to take a seat and picked up the phone, tapping a few buttons. He handed over the receiver and said, “It’s the Superintendent.”

The Supe thanked him again. Then his tone shifted from cordial to administrative. He asked if Big Chuck had received any threats directly, or heard of trouble brewing.

“No, Boss. Everybody in the pod pretty much says they would of done the same thing. Being that it was Wally and all.”

“Well, I’ve received reliable information indicating that threats have been made. Offenders in other units of the facility are saying whoever protected an officer against another offender will quote, ‘get his.'”

“All due respect, Boss, but these gotta be guys with no clue, you know, of the particulars. I mean, who it was, that it was Wally. Or me who helped him. Wally treats everybody decent, and the fellas respect him. And everybody knows me, Boss. I’m sure when they find out–“

“I hear what you’re saying, Chuck. I do. And I’m sorry, I really hate to put you through this.”

“Any way I could send word over to the other units? A note or something? I’m sure they’d–“

“I just can’t risk the possible ramifications. Not when your safety is at stake. I have to take this seriously.” There was a pause, and Big Chuck became uncomfortably aware that the lieutenant, shift sergeant and four guards were watching him intently, scrutinizing his reaction. The Superintendent cleared his throat and continued. “Chuck, where do you want to go?”

He tried to weigh out his transfer options in the way we usually do, considering the known pros and cons of each joint. His mind was reeling beneath the sudden and tremendous weight of being at odds with mainline for the first time in his life. He shrank from the prospect of transferring under such questionable conditions. Circumstances that felt much like protective custody. “If I gotta go somewhere, can I go to Monroe, Boss? I been there before.”

“You have my word I’ll do everything in my power to get you there as quickly as possible. And for what it’s worth, I’m sorry it had to go like this.”

“Ain’t your fault, Boss. It is what it is.”

The lieutenant stood. “I hate to have to cuff you, Chuck. It just don’t feel right. But I can’t walk you to seg without ‘em. Rules. I’m sorry.” He left the cuffs loose around Chuck’s wrists, linking two pairs in tandem to go easy on his broad shoulders.

He paced slowly back and forth across the cold floor of the solitary cell on the ad-seg tier of the Intensive Management Unit. Mentally preparing for the six day wait until the next chain would leave. He thought about how he would present the event to the fellas at Monroe. They would find out one way or another, this much he knew.

“I just never had the memory it must take to be a liar,” he told me months later. “All I could do was tell what happened, and let it be what it is. I can’t sleep or eat my tray, and you know if I ain’t eatin’ it’s serious. Can’t hardly sit down. My mind’s jumpin around like a pachinko ball.”

It’s not as if Big Chuck could show up at a joint and go unnoticed. Having been in prison for much of his life, he knew prisoners at every joint in the state. And, he had designed and built much of the weight-lifting equipment at Monroe, years before. He knew he’d be sought out and welcomed back by most every convict of note. He also knew word of the event would travel to Monroe, if it hadn’t already. The local news hadn’t disclosed his name, but we have other vectors of information. If he chose not to be forthcoming upon his arrival, then when the story caught up to him the presumption would be that he was hiding something. He would have no choice but to pull up the top dogs pre-emptively, one at a time, and tell his side. He did not relish the prospect of recounting the event over and over. Six days of this pacing and mind racing, he thought, until I can just get it over with.

The following morning two transport guards appeared at the cell door, shackles in hand. They stuffed a pumpkin suit through the wicket and directed him to do the dance: fingers, hair and ears, mouth, lift and separate, turn bend and spread. He snugged his hulk into the pumpkin suit and shuffled after them, his ankles chained together. In the sally port an unmarked van where the chain bus staged up each Monday. Chuck hadn’t ridden in a windowed vehicle in over 22 years. They pulled out of the prison and turned onto the two-lane road, his eyes straining to unwrinkle the evergreen woodland blurring past. They wound through miles of the Olympic National Rainforest between the prison and Forks, wilderness in which the Twilight vampires had romped and pouted with their foes. “It felt like we were in one of those road races,” Chuck told me. “I figured we had to be doing at least a hundred, whipping through the curves. Then I manned up and peeked over his shoulder, and the needle said fifty.”

In Port Angeles, they pulled off the highway into a McDonald’s parking lot. They stopped at the drive-through speaker and the guard in the passenger seat said, “Get whatever you want, Chuck. It’s on the Supe.”

“Sorry, Boss,” Chuck said. “I’d love to, but my guts are already churning like a Maytag. What with this transfer and all. If I ate a Big Mac, I might not make it there. And you guys wouldn’t think so highly of me no more.”

“Man is born free, but he is everywhere in chains.” – Jean-Jacquas Rousseau

My boss let slip that the prisoner who’d prevented the murder of a guard at Clallum Bay would be working with us in the Mech Shop. There are only six of us in maintenance, so we usually recruit additions to the crew ourselves. Since we work in what could amount to a shank factory, self-selection is in our individual interests. We would all bear culpability for the acts of one. But this was different. The boss told me this particular prisoner would be arriving the following day, and starting the Monday after. Typically, prisoners must spend at least six months in the institution, infraction-free, before even applying for the gate clearance needed to work in maintenance. The boss said the warden had made an exception and waived the waiting period.

I knew Big Chuck by name, as a machinist and master metal fabricator. Everyone knows who built our weight deck. But the only way you’d find this out is from someone else. Big Chuck, I discovered upon meeting him, is a humble giant with an easy brand of humor and quiet manner. Slow to move or react but quick to share a funny observation or, if asked, his vast metalworking knowledge. Quicker still to share s story–some stories, that is.

Although I’d heard one abbreviated version of the event prior to meeting him, I decided not to place my own curiosity ahead of his comfort. I would rather hear his side organically, as our relationship evolved a space for it. Which it did, after a few weeks of working together. To the best of my recollection, I’ve remained faithful to his account.

Big Chuck’s arrival stirred a mix of reactions. There were not many hugs.

In this yard, each car within a given race has its own area: a sliver of territory carved out along the perimeter of the track. Two pieces of prime unreal estate are known as “rocks,” — low-slung concrete bleachers, each a favorite perch for small flocks of prisoners. Sureños on one, white convicts the other. Both groups are absurdly territorial about who is allowed to sit on “their” rock. The white rock squats across the track from the third baseline.

Shortly after Big Chuck’s arrival, the headline began circulating: He had protected a guard against another prisoner. I happened to be present during the ensuing discussion over whether he should be allowed on the rock. The early push of the discussion was toward declaring him persona non grata. Of those present, I alone had heard firsthand Big Chuck’s side of the story. I felt obligated to speak.

In the pecking order, I am by no means at the top, nor do I have any aspirations to be. But I know the top guys, some well, some in passing. I have more important things on which to spend my limited bandwidth than prison politics. As a rule I create a space cushion between myself and big yard drama. But I’ve always carried myself in such a way that when I do weigh in, my thoughts are considered. Usually. But not this time.

I knew better than to advocate for Big Chuck outright. The general mood was one of hostility, condemnation based on philosophical abstraction rather than critical appraisal of the facts specific to the case. Some made reminiscent comparisons to bygone eras, waxing sentimental toward the climate of retributive violence rampant in years past. “If this had been fifteen years ago, he’d of been greenlit for sure,” someone said, “Captain Save-a-pig.”

“Really?” I said, “Because I feel like that was right around the time they brought a chainbus of rapists, child molesters and rats straight here from 5-wing. (Walla Walla’s protective custody unit.) Most of those cats are still here, very un-greenlit. And the next year they took away tobacco, than porn, and nobody busted a grape. Not me, not you. The next year was personal clothes. Then assigned seating in the chowhall. If I remember right, the only ones willing to roll a raisin to a food fight were the woman in Purdy.”

“There’s no way I’d defend s fucking pig. I ain’t stopping nobody from getting their money on one.”

I appealed to their self-interest. “Well, I was here before Ms. Biendl was murdered in the chapel six years ago. Whether you think the act was right or wrong, it ruined this joint. Ruined it. All these punk-ass rules, the one way movements, the constant codes, the two year limit on jobs–all of it because of the murder. I wouldn’t let that happen again at a joint I was at.”

“I’d take the lockdown and whatever rules they want to make up. There’s a bunch of pigs here I’d love to see get their domes peeled pack.”

I appealed to fairness. “But this guard wasn’t one of them. He was one of the few we have left that treats us like people.”

“Look, it comes down to this: you got them, and then there’s us. Plain and simple. You side with one of them, you ain’t one of us.”

As a last ditch effort I invoked race. “I for one don’t think I could stand around while some African Muslim goes jihad on a white person, cop or not. Tough to watch one of them beat a white man to death and not do something.”

“Pigs aren’t white or black. They give up their race when they put on that uniform. Convicts do not side with pigs. Period. Fuck them, and fuck him for not knowing better.”

I would like to say I took a stand and zealously defended Big Chuck. Or that I demonstrated my disagreement with the mobocratic edict by visibly distancing myself. But I’m not that noble. If I’m going to commit social suicide, I’d rather it be for something I did myself.

My standing is such that my dissent was noted and, although mostly disregarded, not held against me. I walk a line. Survival in prison involves more than simply not dying, which doesn’t happen much anymore. Any prisoner who says they don’t care about their reputation amongst their ingroup is probably a sour grapist. I work alongside Big Chuck. I have learned a great deal from him, arcana of metallurgy and fabricating that come only with decades of experience. And I enjoy his company. He’s one of the few prisoners whose presence doesn’t become wearisome to me after a few minutes. I always greet him in passing, but I don’t walk the yard with him. That would be crossing the line.

Only Big Chuck’s own ingroup handed down a verdict for his actions. The Sureños hate the blacks so much they applauded him. The Norteños didn’t object because the black was African. The Natives withheld comment, although some quietly reprehended Chuck’s conduct. The Crips and Bloods offered no response worth noting. (To my knowledge, they never do.) Individual Muslims have grumbled indirectly, issuing passive-aggressive and toothless fatwas. As a group, the Muslims denounced the attack, presumably because it negatively impacted their public relations without

strategic benefit.

To read part two click here

(Since the drafting of this piece, Big Chuck has petitioned for clemency. The board reached a unanimous decision at his hearing, commuting his sentence of life without the possibility of parole to probation. Nine months later the governor signed off on his release. Big Chuck is awaiting transfer to camp, from which he will transition out to the freeworld within 18 months.)

|

| Steve Bartholomew 978300 WSRU P.O. Box 777 Monroe, WA 98272-0777 |

4 Comments

piscator

February 23, 2018 at 9:39 pmDear Steve,

I am awed by all of the writers on MB6 and have told friends that the essays here remind me of George Orwell's work.

Orwell wrote (or said) that the most important thing he strove for in his writing was to 'tell the truth' — even when he was writing fiction. Orwell avoided literary embellishments, wanting to tell a plain tale with such clarity that the truth, meaning, human element, etc., asserted itself from the story and not the author.

To some degree that seems contradictory and I've thought about it for years. What I think Orwell meant is that he didn't want to preach or to moralize. If a story has something to say, let it just say it!

That sounds simple enough until you try to do it! How do you leave your ego behind and let a story tell itself? How do you give your characters equal weight and not force on them an author's didactic conclusion?

Steve, I think you're doing that rather well in this story! You relate the events, the factions, the biases, the environments, attitudes' etc., so descriptively, with such balance, and without judgment — that the tale tells itself. That's beautiful work!

If you get the chance, take a look at George Orwell's 'Homage to Catalonia.' It's a deceptively simple narrative that just draws you into a foot-soldier's life in the Spanish Civil War. And once you're in, you're never quite sure who's side you're on, or which is the 'right side!'

It's one of my favorite books and it might be a model for the kind of narratives you folks are working on at MB6.

I wish you all the best! And you can be sure, I'll keep reading!

Sincerely, piscator

A Friend

January 31, 2018 at 6:17 pmThank you for your generous offers to donate to "Big Chuck." I agree that his actions are inspiring! I don't have permission to share his name publicly, but if you send your donations to "Big Chuck" c/o Minutes Before Six, we will ensure that he receives them. Thanks again so much!

Jenneke

January 30, 2018 at 2:21 pmWhat a nice gesture. If possible I would like to know the name of this person as well so I can make a donation too.

Anonymous

January 27, 2018 at 12:31 amPlease send me his name so I can send him twenty dollars