By Steve Bartholomew

(To read part one, click here)

The Convict Commandments:

1) Thou shalt not rat

2) Thou shalt not have on your jacket sex offenses nor violence toward children

3) Thou shalt not break your word (to your fellow prisoner)

4) Thou shalt not steal (from your fellow prisoner)

5) Thou shalt mind your own damn business

6) Thou shalt not seek protection from staff for any reason whatsoever

7) Thou shalt not shirk a debt, nor forgive your debtor

8) Thou shalt not tolerate disrespect or aggression, nor back down from a fight

9) Thou shalt neither sympathize nor fraternize with The Enemy, your keeper

10) Thou shalt forsake whosoever breaks these commandments

“[A human being] experiences himself, his thoughts and feelings, as something separated from the rest, a kind of optical delusion of his consciousness. This delusion is a kind of prison for us, restricting us to our personal desires and to affection for a few persons nearest to us. Our task must be to free ourselves from this prison by widening our circle of compassion to embrace all living creatures and the whole of nature in its beauty. Nobody is able to achieve this completely, but the striving for such achievement is in itself a part of the liberation…”

|

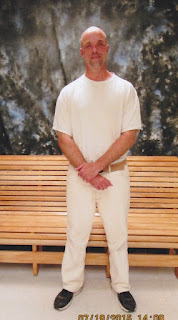

| Steve Bartholomew 978300 MCC/MSU P.O. Box 7001 Monroe, WA 98272 |

3 Comments

polarbeardave

February 2, 2019 at 2:00 amGreat story, wonderful writing. More people need to read this.

urban ranger

February 1, 2019 at 1:40 amAs always, definitely interesting reading.

Thank you, Steve.

Lisa Resnick

January 31, 2019 at 2:22 pmNice post.Keep sharing. Thanks

clipping path