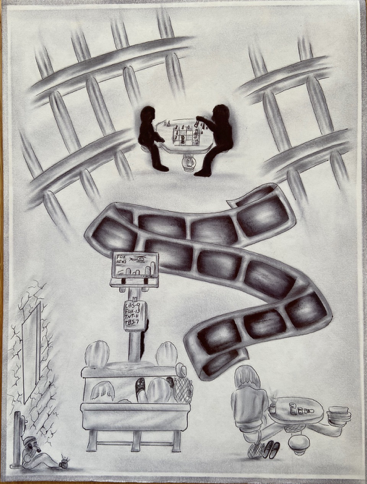

Illustrations by Byron Boone

A dusting of freckles,

a laugh, perfect and free, someone he’d known:

a grasping.

A moraine of rusted debris,

a seeping tunnel leading to a ladder:

upward, to stars.

A tiny, gray feather,

perfectly formed, held in the center of a small cage:

an empty hand.

The whoosh-bang of a crash-gate, somewhere in the middle eternity.

The sodium-vapor glare from the run-light intruded, casting yellow lines like a barcode on Marlow’s face. The ghost of a frown formed, and he briefly tried to pull the balloon of his dream back from whatever ethereal realm they fly to once the helium is let out of them: something about a face, and a tunnel, and stars. After a long moment, he sighed. He was far enough over the border into consciousness to know this was never going to happen. Not on any day. Certainly not this day.

He cracked his eyes open, one hand pressed to his forehead to block the radiance. “Hail, holy light,” he grumbled. His clock radio blinked angry, red nonsense at him, so he reached for his wristwatch: 2:48am. A little earlier than his usual reveille. He’d wondered if this would happen, if he’d even be able to sleep at all on Discharge Eve. Despite everything, he felt… well, normal, if that word had any meaning in a place like this, to a person like him. You never really know, he mused, just thinking about it all in advance. You make your plans and try to prognosticate as best you can, but in the end you just have to go through it to know. How many stomp-down cons had he seen do something remarkably stupid and self-defeating in the weeks before their release dates? Southwest T beat up his cellie, got four stacked on him by the courts for a cracked skull. What was that Mexican’s name who slapped the warden? Feo? Something like that. He was already waiting to go on chain to pre-release. He definitely got extra time for that shit. Then there was Chickenhawk. That idiot stabbed a commissary trustee thirty days before discharging on a twenty-five. All over a two dollar bag of coffee, too – although, of course, it’s always about far more than just the asshole standing right in front of you.

Marlow paused a moment, listening to the sound of a pipe chundering behind the walls, the inevitable result of what happens when your engineers’ hydrostatic acumen is far surpassed by their jerry-rigging creativity. It might have been Fast Black who stabbed the trustee, he reconsidered, trying to dredge up a stable memory of a face and getting nowhere. Fuck, he sighed finally, closing his eyes again. Everybody sort of runs together after a few decades, everything and everyone redlined reflections of other people and places. I guess that’s how you know you’ve been locked up too long. Not that he needed anyone to tell him that. His body had so many scars, they were practically integral to his overall structural stability by this point; take them away, and he might crumble into a million pieces. Unlike his radio, they always told excellent time.

Marlow finally sat up, pulling his covers off. The brilliance from the security light caused him to blink, then wince. The bite in the air sank its teeth in deep, even with the three grills glowing orange in the back corner, hanging from Licky’s clothesline. To his left, bars. Beyond that, concrete, more bars, more concrete: eventually, a wall of begrimed windows.

Everything was essentially a shade of gray, as if he’d had all of the cones sucked out of his eyes. He thought of Rilke’s panther, then put that metaphor away for the last time. I’ve used it too much anyway, he thought, then shifted mentally in reverse, focusing on that “last time” bit. He turned this phrase over and over again, testing the weight of it, something simultaneously too heavy to imagine and yet lighter than a fantasy. No fear, he concluded at last. A little nervousness, but nothing he couldn’t control, nothing he couldn’t hide until the ref blew the whistle. Satisfied, he grabbed his socks off his own clothesline and put them on. The cold in the concrete floor telegraphed through almost immediately, not impressed by the thermal claims of state cotton. He reached up into his side of the locker suspended above the cell’s door, careful to minimize the creaking of the hinge. Not that it mattered. Anything short of an overhead thermonuclear detonation was unlikely to wake his cellie, especially when the homo insipiens in question had spent the previous evening downing bottles of prison hooch. Marlow could still smell the sickly-sweet stench wafting off the upper bunk, like an oily cheese stuffed with gangrenous flesh sprinkled with decaying flowers. Still, maintaining decency and civility was a choice. It mattered even when no one noticed. Maybe especially then, he thought.

Three steps from locker to sink. Seventeen seconds to fill his hot-pot. Two minutes and forty seconds for the pot to get warm enough. He didn’t even need a telencephalon to do this, so deeply engrained was the habit. As he reached for his razor hanging from a makeshift hook glued to the wall, he noticed movement down in the shadows pooled in the back corner of the cell. He paused briefly, then took two steps back and switched on his lamp. Nestled in the corner in one of Licky’s old shirts, one of the facility’s semi-feral cats glared at him, clearly wondering exactly what the fuck this human was doing in its personal space. Marlow knew better than to try to pet it, as much as he would have liked to. Instead, he returned to his cabinet and removed a small plastic bowl and a three ounce packet of mackerel. The cat tensed up when he placed the bowl down near the corner of the bed. Marlow returned to the sink. It’d eat it or not. Could go either way, he knew. A normal cat would have been on that bowl like a fat kid on a cake, but prison cats were survivors. Like everyone else, they knew few gifts were truly free in these halls.

Marlow brushed his teeth, then shaved, ticking off new lasts: the last time he’d have to use a contraband handheld mirror, final application of these bullshit, non-commercial grade razors the state picked up cheap from Xinjiang prison labor camps. Won’t miss any of that, he thought. Before putting the mirror away, he took a long look at himself. The man who had stolen his reflection years ago stared warily back at him. It wasn’t a great face, definitely not 1.618 perfection. It had once been maybe marginally attractive, when he was young – nothing to brag about, but not so awful that it made women and children run screaming for the hills. He couldn’t really track the temporal lines that led from that face to this, from that sense of I-ness to the present one, and he wondered if this was normal. Are we always mysteries to ourselves, always discovering that we really don’t understand how we became the people we are? Probably not, he decided, slipping the mirror between Licky’s mattress and the metal bunk; his cellie would find it on his own schedule. Most people are probably lucky enough to slide softly casual from day to day, identity seemingly intact. Here one fell into each new dawn like tripping down a set of stairs. Who you were at the end of the day seldom matched who you’d thought you’d been or planned to be. Everyone plummeting forever, separated by mental bars that the real bars convinced you were some kind of universal constant. Everyone thinking they were flying because they lacked the perspective to tell the difference between that and falling.

That was the goal, he knew, filling a cup with instant coffee grounds and pouring in some water from the pot. Refashioning the subjectivity of those incarcerated, imprinting those bars on the self. Of course, back then, there were people who actually wanted to create a new subjectivity that was genuinely better morally, or at least more useful to bourgeois society. He didn’t know exactly when that set of goals got drawn into the dark corners of cost-cutting, conservative political posturing, and “management techniques” and was unceremoniously shanked to death, but that butchery took place long before he’d ever first been reduced to a number. Hardly anyone got better in this place these days; hardly anyone even knew they were supposed to try.

He sat back on his bunk and settled against the wall. The heat from the cup warmed his fingers. The bowl was now empty of mackerel and the cat gone, off on its own feline pursuits. He’d never even heard it leave, he marveled: the best kind of cellie. Sure wish there’d been more of them like that, he thought, mentally flipping through a motley flashcard review of the various ill-behaved primates he’d been forced to share a six-by-nine foot cell with: the chronic masturbators and the chemical dependents, the fist-fights, the arguments, the stenches, the messes, the three times he’d gotten smacked in the face with a stream of 2-chlorobenzylidene malononitrile gas because his cellie was tripping out on K2 or bath salts and wouldn’t cuff up on command. Wouldn’t miss any of that either, he nearly said out loud. That was going to end up the day’s leitmotif, he figured, if he wasn’t careful. Probably unavoidable, he decided after another moment’s thought.

Somewhere down on Three-Row, he heard the slow clinking, jingling sound of a set of keys swinging on a screw’s belt. He listened to this discordant melody of oppression as it reached the end of the run and grew chaotic and angry as the officer hefted his way up the stairs. He could hear him mumbling names out loud and tapping bars with something solid as he paused at each cell. Seconds later, an obese man in a gray uniform heaved into view, the ring of keys just one of a bewildering array of the tools of modern corrections attached to his belt: handcuffs, baton, mace, matte black flashlight bright enough to send coded messages to Proxima Centauri. The uniform itself was faux-military in design, poorly fashioned, and even more poorly maintained: essentially metonymic for the system of which the officer was representative. His attention was focused on the count-sheet in his hands.

“Marlow?” he muttered, before looking towards the lower bunk. Seeing him awake, he grunted. “Mornin’.”

“Good morning, Mr Merces.”

The officer shifted his eyes upward. “Schauerlich? Licky?” the man inquired, tapping the bars with a pencil. “He alive up there?” His voice was a strange, smoky form of a rasp, as if he’d done a great deal of screaming once upon a time and had broken some integral piece of anatomical machinery.

Marlow paused for a moment. “He’s breathing,” he responded finally, avoiding the more difficult aspect of the question. “He’s just hard of hearing, is all.”

“He’s hard of listenin’. Different problem ‘tirely,” Merces responded, and then leaned in, sniffing. “Nossir, this here soldier was downed by the type of ordinance that you gotta uncork before bein’ deployed. Hope you got you some pills for his fat ass later.”

“’In our father’s pharmacy are many prescriptions.”

Merces laughed, hitching his belt up against his gut. “Amen to that. Breakfast carts is downstairs. Didn’t smell no syrup. Ain’t makin’ no promises, but could be eggs.”

“Will wonders never cease,” Marlow quipped, but the man had already hauled himself to the next cell. He sat there, listening to the sounds of the prison as it dreamed: far down the run to the left, he could hear the low oompahoompahing of Norteño music coming from the speaker he’d made for Cacuy; in a few hours, once the man knew everyone was awake, they’d be able to hear that thing all the way over on D-Line, what with all the magnets he’d used. A few minutes later, the crash and bang of the food carts as they rolled into place, the shouts of the kitchen crew as they loaded the carriers and started lugging them up the stairs: clank, slam, ding, the daily 3:30am-ish wake-up call.

Marlow waited until they were two cells down before slapping the palm of his hand against the underside of the bunk. He listened for a response; hearing nothing, he repeated the motion with more force. He’d never actually heard a pig go truffling before, but he imagined it might sound a lot like his cellie as he was trying to wake himself.

“Breakfast,” Marlow called out.

“Gah.” This was followed by audible smacking sounds. “The devil raise a hump on you.”

“He may yet. You want this slop or not?”

“The fuck time is it?”

“3:39.”

“Bitch-ass motherfuckers need to learn to light their shit without blowing the breakers,” Licky groused, and Marlow heard the click of buttons as his cellie reset his clock. Licky continued to grumble about his idiot neighbors as Marlow stood up and moved to the door. He didn’t really mean any of it, he knew. His moaning was really just a function of potvaliancy mixed with envy; eight hours from now, he’d be done with his post-partyum depression and would return to his normal, gregarious mode – and if any of the people who’d tripped the breakers offered him one of their joints, he’d accept and then smoke the thing at near-relativistic speeds.

Officer Merces entered stage right, using a long steel bar to pop open the tray slot. A pair of kitchen workers followed him, one holding aloft a metal tray carrier, the other handing the trays to the men in their cells. Sure enough, Marlow saw, there were two fried eggs in the main slot, a minor miracle in this wasteland of perpetual pancakes. He accepted both trays, and handed one up to Licky. Before Marlow sat down on his bunk, he reached into his cabinet for a bottle of jalapeño squeeze cheese and some black pepper. He waited for a few seconds before handing the bottle upstairs. “Cheese?”

Licky responded with a gripe, something about his hoe-ass mattress being all hogged-down and wallered out in the middle, but he took the bottle. Marlow followed this with the pepper. It, too, disappeared. He ate the oatmeal and the pear slices, and then lifted the rest of the tray into view. “You want these eggs?”

“Hell yeah, I want them eggs,” Licky answered quickly, sounding almost civil for the first time. “You got any jalapeños?” Marlow smiled at the way he pronounced the word: jal-o-pee-nos.

“I already gave you the last of my cheese. Greater love hath no man…”

“Shite and onions.”

“Ain’t got any of that either. Running low on patience for your mouth, too.”

Marlow sipped his coffee and waited for his cellie to finish. Watching Licky try to climb up or down from the top bunk was an almost painful act, one that always made Marlow wish he had a crane handy. Not enough to inspire him to swap bunks, of course, but Marlow was happy enough to compromise by elevating things like trays up to him. It wasn’t the only way that Licky regularly took advantage of him or his status, but Marlow didn’t mind it all that much. One learns the difference between an epiphyte and a parasite pretty quickly in this place; when it came to cellies, the former was about all one could hope for. Besides that, after everything – or perhaps because of everything – he’d realized that it’s just much simpler and easier to be hurt than it is to hurt. If l know anything, he thought, anything true, that’s it. Fortunately for them both, Licky had a champion-grade bladder, or the situation might not have worked out so well.

Licky lowered the trays. Marlow took them from him and slid both out through the gap under the door. He could see his cellie in his peripheral vision as he checked a few of the bottles strewn about his mattress for any hooch that might have evaded him; finding none, Licky sighed, and laid back down again. Marlow waited until the man’s breathing slowed before he switched on his radio, keeping the volume low. The only station coming in clearly was the alternative rock one, so he left it there, and again leaned back against the wall. Licky would understand why he hadn’t told him he was getting out today, he knew. Word goes around, predators begin to circle, looking to claim your property, your contraband, your connections, your peace of mind, maybe even start some trouble that could mess up your parole, maybe get you some stacked years dumped on you. Marlow wasn’t superstitious in the least, just well-trained to keep his business to himself. Licky’d get it; he’d miss him for a week, and then he’d return to the drama of his own louche solipsisms. The man’s needs were pretty simple. So long as his family continued to send cash to his account, he could get drunk daily, high weekly, and stay permanently fat. He had no real goals or dreams beyond that, didn’t really care to have “fancy-shmancy idears”, as he called them.

Marlow often wondered about what it would be like to be naturally free from such things. Systematically and surgically killing off his dreams was a daily occurrence for him, so to a certain extent he acknowledged the sense of… well, not “peace” – that clearly wasn’t the right word for this thing Licky had – “simplicity”, maybe? Yeah, he thought, that worked, though I’m being charitable: the simplicity of Licky’s existence. On the other hand, he didn’t seem to possess much of a soul at all, just one big reflex arc; needs and passions either slaked or denied. Marlow took another sip of coffee. ”Soul” wasn’t really a good fit, either. Could such a word even be used seriously in an age when Cartesian dualism was such a joke? There wasn’t really a secular analog, though. “Spirit” was still too tinged with naïve metaphysics, “entelechy” and “holons” were both too technical, “sophisticated level-crossing feedback-loop-imbibed intentional agent” too much of a mouthful for casual conversations. Whatever; “soul” worked as a shorthand for what he was aiming at. Some people just seemed to have more of one. Babies had almost no soul, but it grew in them as they aged. Old-timers with dementia had lost theirs, human-shaped shells deprived of the essentially human. Everyone else in between sat on a spectrum. None of us here have had much of one, apparently, he thought ruefully. Or maybe society had just decided ours weren’t worth respecting. That would probably seem like opposite sides of the same coin to most people, he knew. He didn’t think so, but he knew he’d have a hard time convincing a civilian of that. On the radio, Fleet Foxes were singing about being raised as snowflakes but preferring to be a cog in a great machine, serving something greater. “What’s my name, what’s my station?/ Oh, just tell me what I should do.” Marlow grunted and reached over to turn the radio off.

Silence reigned for a time before somewhere on the row below him an alarm went off; after a few seconds, it was silenced. A few minutes later, another could be heard to his left; then another, and another. Wake-up time for the field-squad – what used to be called the “hoe-squad” before that word was kidnapped by the zeitgeist and dramatically redefined. Marlow stood up and reached into his cabinet. He flipped through a series of small, folded pieces of paper, each carefully glued shut and printed with the nicknames of fellow convicts. Each had two stamps taped to the outside, the penal equivalent of cab fare. He paused. No, better call them two oboli, for Charon’s ride across the Styx. That was a decent allusion. I’d write that down if this were any other day, he thought. It wasn’t, though, so he selected one of the notes and then removed a pencil that had a small piece of mirror glued to one terminus. He angled this through the bars when he began to hear door locks being released by the officer manning the controls in the rotunda. A couple of cons in tattered work gear and boots grew larger in the mirror’s reflection and then sleepily trundled past. A minute later he was able to pick out Ironwood’s bulky frame approaching his door. The man pulled up short, having seen the mirror.

“Morning, ‘Wood,” Marlow said, sticking his hand out. The man shook it, palming the kite.

“Charles. What you got for me?”

“Delivery for Chino Li, plus a couple of flags for your trouble.”

“Aight,” he said, leaning closer to the bars and inhaling. “Jesus H. Christ. Licky, you fat fuck. You think you could make it any more obvious?”

“Let the man’s liver die in peace.”

“This hot?” lronwood asked, nodding towards the diminutive package.

“Not even a little bit. Message only, encoded. You get jammed up, give it up.”

“Okay. I may have something I need your help on next week. Won’t know for a few more days.”

“I’ll be here,” Marlow lied.

“Later, then,” Ironwood replied, then paused, turning back. He gave Marlow a lengthy inspection, his head tilted slightly to one side.

Marlow jammed down on his kill switch, voiding his features of all affect. “What?”

“No… it’s nothing,” Ironwood responded at last. “It’s just that you were smiling. Don’t think I’ve ever seen you do that before.”

“Get out of here,” Marlow waved dismissively, turning back to his bunk so the other man couldn’t see his face.

“No, seriously. You’re like exuding all kinds of happiness or some shit.”

Marlow lifted an arm and sniffed it. “Must be this new soap. Got to go back to the old stuff that put out only misery and loathing.”

“Come to find out Licky gave up the booty last night,” Ironwood said, elevating his voice as he reached in to tap the sleeping man’s head.

Marlow grimaced. “And here I was, having such a nice morning.”

Ironwood cackled as he strode away. Licky remained blissfully unaware of the entire exchange.

It infects us, he thought, so quickly. The things we see every day: violence, rape, indifference. We try to joke about the monsters that turn us to stone, to rob them of their power: and yet we get there all the same, laugh or no laugh. He moved to the back of the cell and unplugged one of the grills. He left it hanging for a few minutes to cool off, the almost complete circle fading from orange to reddish-gray to merely gray. Once he was satisfied it could be touched, he wrapped the cord up and put the entire device into a brown paper sack. We turn away from each other and all the chains of interdependence, become radically alienated, and then label this a virtue. Maybe that’s what the soul really is, an increasingly developed sense of participating in a grand “we”, he thought. If so, Licky’s not the only one without a soul. In fact, in terms of the percentage of his humanity that he’d lost in prison, he was probably doing better than most of us. At least he’d managed to smile once since the late Cretaceous. “Oh, just tell me what I should do,” Marlow whispered quietly to himself.

At 7am, the locking mechanisms on the doors began popping open, one after another, a weird domino-cascade that began on his right and overtook him to pass to his left. Every single time, he thought, it never fails: a memory of the damned “wave” from the Double-A games his uncle used to take him to when he was a kid. What was that, four decades ago? And still it’s hard-wired in there, this desire to raise his hands and shout “Weee!” as the locks whizzed past. Instead, he tucked a set of three kites into his shirt pocket and the brown sack under his arm and stepped out onto the run. He was joined by eight or ten guys from his row, all headed in the same direction. By the time his group had trudged down the stairs and reached the dayrooms, half a dozen guys from Three-Row had already entered and flipped the two televisions on. Marlow wasn’t big on spending much time in the dayrooms, so he moved to the windows, giving the detritus time to sift into the form it was inevitably going to take: whites at these tables, blacks over yonder, Hispanics in their place. Once he was satisfied he understood the layout, he settled into a seat with his back to the wall and a view of the television showing the morning news.

The noise began almost immediately: dominoes clacking, televisions blaring, a rising tide of coprolalia – all of the ruined, mental drain-swirl that passes for thinking in places like this: the psychic equivalent of third-degree burns when applied over the course of a life. The room itself contributed to the assault, being all right angles and hard surfaces. It was like the building had no clothes on, he thought, the perfect place for noise to echo and reverberate, just bouncing around until it impacted the only soft surfaces available: us. Like rain on statues, he decided: same results. He focused on a young Mexican flashing sign language across the open space of the rotunda to someone in another wing. The man clung to the bars with his left hand, looking like nothing so much as one of Harlow’s baby monkeys, snuggled up next to its wire mother. Might be more to that simile than mere appearances, Marlow realized grimly. For some of these kids, this place has been more of a parent to them than their original gene donors ever were.

Manos arrived an hour later. After greeting the assembled Hispanics, he launched into his workout routine near the pull-up bar. Marlow had to hand it to the man: despite everything, he was religious about his fitness regimen. He’d never asked Manos exactly what had happened to him; the bullet wound scar was an obvious clue, though. The rumor mill had it that the cops had really fucked him up during his arrest, but the precise circumstances were unknown. Whatever had happened, it had left his hands awkwardly angled, three fingers on each splayed out, the pinkies bent inward: thus his nickname. His back had a strange lump on it, the result of some kind of fusion operation. He’d tried to cover up some of his scars with angry, violent tattoos, but the effect ended up looking like the vast majority of prison tats: an acupuncture map of male insecurity. Despite all of that, he’d never once heard the man complain about much of anything.

A group of SSIs passed the dayroom cage, pushing brooms and a mop bucket. Marlow called one of the ones he trusted over. “Three times for M- and N-wings,” he muttered, hanging his hand outside the bars. The man accepted the notes and the accompanying stamps. On the way back to his seat, he called Manos’ name. The man looked up, halfway into a set of burpees. “When you finish your workout, come see me.”

“Aight. Estaré contigo enseguida. Hoy no me apetecía este jale. Don’t know why. Some days you just ain’t feeling it, sabes?”

Marlow nodded and returned to his seat. A CGI squid tried to sell him car insurance for the fourth or fifth time that morning, and he closed his eyes; there weren’t enough savings in the world big enough to reward with his business a company that created such imbecilic advertisements. This is the last time, he thought, that he’d ever have to be locked in a cage like this, watching the Ayn Rand marching band pundits on Fox Noise spin their lying hickpolitik for the booboisie, the last time he’d ever have to worry about crossing some unseen line laid down by racial troglodytes, the last time –

The bench rocked as someone sat down on his left.

“Ésta no es la clase de vecindario por el que se puede pasear uno con los ojos cerrados, homie,” Manos said, breathing deep.

“I have other ways of seeing,” Marlow replied ominously, opening his eyes to slits and turning slightly to face the other man. “For instance, I know what really happened to Greenspoint’s jag last autumn. I’ve also seen what you’ve been up to with Ms Gonzalez in the commissary storeroom. I’ve seen what –”

“Okay, okay,” Manos hushed him, looking around to see if anyone had been close enough to overhear. “Pinche gabacho escandaloso,” he replied, smiling. “Point made. What’s new?” he asked, clapping Marlow’s hand.

“Not much. Como te encuentras? How’s business?”

“Meh. Otro pinche día en este infierno. I started out with jack shit and I still have most of it left.”

“Not the way it looks from my cell. Looks to me like you’ve been cranking out about a hundred bottles a week.”

“Closer to one-twenty,” Manos bragged. That was the second thing Marlow liked about the man. Like him, he had no one outside the prison helping him out with anything. Manos relied entirely on his hustles to survive; in his case, this meant making booze. A good racket, though one the administration would come down on like a ton of bricks if the wrong ranking officer found out who was behind it.

“No flak from the juras? Merces zeroed in on Licky this morning, by the way.”

“Merces minds his business. Anyways, riesgos asumibles son el precio a pagar por hacer negocios. Si yo no hubiera estado preparado para ellos, lo mismo podría haberme quedado en casa.”

Marlow nodded. That’s what we all should have done from jump street, he acknowledged. “Speaking of Licky, how deep is he in now?”

Manos sat still for a moment, reviewing his mental ledger: the only kind allowed in prison. “Forty-two flags.”

“He paying up consistently?”

“Mostly. He’s a little behind now, but he says he has something in the works with a prima of his. Probably bullshit to get me to keep giving him credit, aunque no pienso apostar contra nada que tenga que ver con ese hijoputa – he keeps surprising me, you know?”

Marlow knew. He flipped open his ID holder to the hidden pocket he’d sewn inside and withdrew some stamps. He counted out sixty.

“There’s for the debt, and eighteen more for the next six bottles. Tonight, right?”

“Much appreciated. I’ll come his way just before shift change. I’ve got a new batch I’ve got to pour off, six days old, good stuff.”

Marrow nodded, then transferred the brown paper sack from his right side to his left. “Want that?”

Manos opened the bag slowly, as if it might contain a viper. Seeing the grill, he removed it and checked the connections. “Daria mi cojon izquierdo por eso,” he said at last.

“Bleh. I’m not charging that much. In fact, I’m not charging at all. It’s yours.”

Manos looked up at him, his eyes searching Marlow’s face carefully. His features finally softened and a small smile crept across his lips. He understood. He thinks he understands, Marlow corrected himself.

“Carnal… I don’t… We go back a ways, don’t we?” Manos stopped himself after these words, blinked once, and then continued, all business. “How do I use it?”

“You need to scrape the metal off the top of your bunk. If you are ever in a cell that has a desk, you can use that too, since it’s a lot less metal to have to heat up. That’s your cooking surface. You’ll need to construct a pillar of some kind – most of the guys use books followed by soda cans at the top. You just need to make sure that the whole surface of the ring there is pressed firmly to the underside of the bunk, so it transfers the most heat possible. Now, full disclosure: If you are cooking for yourself, one grill is enough. If you are planning to set up some kind of production line for a restaurant, you will want to use some of your profits to get a couple more.”

“Bro, I’m gonna open my own grill to go with my bar. My ‘micro-distillery’, I mean,” he quickly corrected himself, making little air quotes with his bent and broken fingers.

“If you can find a flat piece of metal, you can dispense with the bed or desk entirely. There’s a nice five-by-fourteen piece of steel that sits underneath the keyboard on the typewriters they sell us. You have to open the machine to get it out, but once you do, it works great. Just set the grill on top of three soda cans, and then rest the plate on top of the grill. Viola.”

“And I just use butter, right?”

“Yeah. The kitchen workers will sell you bricks for a dollar. Or you can use the sandwich spread from the commissary, since one of its principal ingredients is soybean oil.”

“Always wanted one of these. I just never knew how to get the maldita element out of the hot-pot without breaking it.”

“It’s not hard. Honestly, it just pops out once you get the bottom casing off. On nights when it’s cold, you can hang the thing up and plug it in, and it works like a little space heater. It’s not going to be an immense change in the temp, but it does help.”

“Sandwiches go for what? Two for a buck-fifty?”

“Yeah, same with tacos,” Marlow responded, his attention shifting back to the dayroom. A young Mexican was using one of the electrical sockets to light a joint. Marlow decided it was getting on time to leave. “Break Licky off with something to eat every once in a while. That panzón of his needs constant attention.”

Manos laughed. “His gut is going to kill him some day.”

“I’m still betting on his mouth doing the honors, but you may be right,” Marlow sighed, sticking his hand out. “Until we both get what’s coming to us.”

Manos took his hand, shook it, gave him one last long look, and then went to rejoin the Hispanics and show them his new toy. Some of the white boys weren’t going to like that, Marlow thought, as he walked to the dayroom’s gate. Grilling was Caucasian territory, like one racial group could actually attempt to patent an entire form of cooking for themselves: silly. He waved to an officer in the rotunda. After a few moments, she noticed him and flipped a button on the control panel and the gate clicked open. So long to that business, he thought, returning to his cell. What had Manos called it? “Another day in hell”? It might be that for him, he admitted, a sort of constant failing at what he probably wants more than anything else: to be physically healthy again. Definitely a Greek conception of hell, all those push-ups, trying to twist his arms in order to get a clean movement. Closer to Tantalus or Sisyphus than a Christian’s eschatological intuitions: an endless repetition of the same failure in lieu of the Eternal Bonfire. He piled the last of his books into a mesh bag, plus a quarter bag of coffee and his last Snickers bar. That’s really why I like Manos, he realized. Whatever he did to get here, he’s paying; he’s probably paid more than he should have, he’s in the black. Whatever the courts or society had to say about guilt and punishment and debts, he’s given back more than he could have possibly taken, considering he’s here on a dope case. Marlow fumbled for the right concept before settling on another religiously-tinged word: redemption. Not a term one heard much in this place. There’s no room for it, really, he thought. But that’s what Manos had. He was square with the house.

Marlow checked his watch: 8:45am. He started to count down the hours and then forced himself to stop. I can’t be doing that all day, he thought. It’s nearly over with and that’s good enough. He reached out to gently push on Licky’s shoulder. Getting no response, he shoved harder.

“W-what?”

“I need to leave for work. You going in?”

“Fuck. Fuck it, no, I’m…” Licky paused, then sighed. “Yeah, I got to go. Can’t get fired again, or the major says he’s gonna stick me in the fields.” He slowly sat up. “I could kill Christ for a drink.”

“Or, you could take these four ibuprofen and murder no one. Your call. I’m gone,” Marlow said, leaving the small packets of medication on the top bunk. He grabbed his bag and headed back down the steps. Licky was right about one thing, he couldn’t afford to get axed from his SSI job. He’d already gotten kicked out of the kitchen for reasons which surprised precisely no one save the kitchen captain. He’d tried to train with the electricians, but decided there was too much “theory” involved – and by that he meant “work”. So, this was it: push a broom three days a week for a few hours, or go till the fields. Officer Lopez was stationed at the wing’s crash-gate, checking off the names of the men as they filed through.

“Marlow. Library,” he stated, holding up his identification.

“The bag?” she asked, looking down.

“Books for donation, personal coffee, half a kilo of cocaine,” he joked, watching her face carefully as he did so.

She laughed. “If only you were serious, I might actually have a shot at liking this job for once. Now: get.”

Satisfied by her response, Marlow followed a line of prisoners wearing threadbare green jackets down a long redbrick hallway, watching small groups peel off at various junctures: Big Red and Wyatt for the maintenance bays, Moises and No Limit for the Sarge’s office, a large group headed for the schoolhouse. He followed this latter crowd, only diverging by a couple of doors once they arrived at the education facility. Through a long set of windows, he could see into the Law Library, where the usual assortment of jailhouse lawyers and writ writers hung out their shingles and engaged in continuous and almost universally unsuccessful lawfare. 44 was seated at a table in the middle of the room. Marlow thought about stopping in to check on his progress, but decided against it. He would comply with the contract, he assured himself. That was out of his hands now. Marlow continued down the hall until it dead-ended at the Recreational Library.

That was really too grand a name for the place, he reflected for the umpteenth time, as he pulled the door closed behind him. The Bodleian or the Beinecke it was not. The Library Closet would have been more accurate, the Library Nook that the administration permitted more from a sense of tradition than any real understanding of recidivism reduction theory. And yet, these roughly 600 square feet were his: the wooden shelves bravely losing their battle against entropy, his; the suggested reading lists, entirely his. This was the place he’d poured his time and energy and care into for sixteen years now; his attempt to create a safe place for minds to expand. That was the goal, at any rate. He wasn’t sure how much of that had actually taken place over the years, how many humans had been saved. Less than he’d have liked, certainly; more than some in the freeworld or the legislature would credit, probably.

Officer Clarke was lounging in his chair in his small office, the only other person in the library. That wasn’t unusual for this time of the morning. Most days, his boss spent a good three-quarters of his shift planted in that chair, in various stages of flirtation with the phases of the sleep cycle. Clarke was content with allowing Marlow to run the library, and Marlow was content with the old man leaving him the hell alone.

Marlow spent an hour cleaning, giving the space a thorough dusting: another personal last, and more than likely the last such cleaning the space would experience for some time, knowing Clarke. He logged in the books he’d brought with him, placing the appropriate labels on the spines and adding them to the registry. He then filled the orders from the hole and close custody. He’d procured a list of all of the men in the administration-segregation wings, and each week he selected twenty or thirty names of guys who hadn’t ordered anything and sent them works he thought might help them or spark an interest: Viktor Frankl’s Man’s Search for Meaning, Jerry Coyne’s Faith vs Fact, A.C. Grayling’s The Refutation of Scepticism. By the time he’d loaded the carts up for dispersal, it was half an hour till noon and the first of the GED classes were being let out. A dozen or so of the guys with time to kill on their lay-in cards stopped by to gossip, to maybe see if there were any new deliveries. Marlow was a consistent pesterer of all of the organizations that donated books to prisons, so this was a fairly even bet on most weeks – even if he was continually disappointed to view the sorts of titles they were interested in. Dean Koontz might be a step up from mere barbarism, but it was a very small one.

The lunch hour approached and the crowd emptied out, leaving only Marlow and Winston, the Ed-Building’s teacher’s aide. A formally educated scholar amid a heathen mob of autodidacts, Winston had always reminded Marlow of one of those isolated bookworm types from a Chekhov story; the parallels between poor Southerners and Russian peasants were striking and so obvious he had a hard time understanding why no one had ever written a book on the subject before. Winston had annexed an entire table near the back corner, loose papers and various titles spread out before him, his pencil darting across one of the former, eyes the latter. Marlow checked on Officer Clarke’s state of wakefulness; finding him suitably engrossed in a thorough review of the backsides of his eyelids, he took a pair of cups off the man’s desk and filled them with coffee from the percolator. Taking the seat across from Winston, he plopped both cups down in the middle of the table.

“Warden comes in while you are drinking that, you didn’t get it from me. But don’t worry, I’ll make sure you have plenty of reading material when he assigns you to the hole.”

Winston laughed, setting down his pencil. “Get thee behind me, Satan,” he quipped, reaching for one of the cups. He took a long sniff and then a sip. “But not that far behind me. Criminy, that’s good. You forget what real coffee tastes like after downing gallons of that instant crap they sell us.”

“One of the perks of the job.”

“There are others?” he asked, looking around skeptically.

“Scintillating conversation. Don’t let me down now,” Marlow responded, leaning over to extract one of the books from a small pile Winston was using for his research. He saw it was one of Frank Dikötter’s recent works on Mao. “What brings you into my little corner of paradise?” he asked at last. “I never got around to these. Essay, or short story?”

“I think you are forgetting the most important feature of any paradise, my friend, the only thing that prevents it from eventually devolving into a hell: an exit door.”

Marlow acknowledged the point, then rotated his index finger around in the universally understood signal for ‘get-on-with-it’.

“Story, but it’s got a didactic core, because I can’t seem to be able to help myself. Freud wrote that you could judge an author by how he treats his readers, and I think I must be a horribly cruel god, because I keep requiring mine to have saintly levels of patience and understanding. Anyways,” he said, pushing his glasses back from the tip of his nose. “I had wanted to write about the Chinese Communist Party in 2019, during all the protests in Hong Kong, but I couldn’t ever figure out how to do it. You know, a prisoner writes something about someone or something, and he automatically discredits that subject just because of who he is. I didn’t want to harm a movement I deeply respected just because of my own moral failings.”

“What’s changed? Unless my eyes deceive me, you are still locked up.”

“Two things. First, I switched from wanting to write an essay to a piece of fiction. It took me a minute to find my way into the story, to shrink it from some kind of grand polemic down to the essential tale I wanted to tell. There was this incident in Yuen Long in 2019, where a bunch of triads beat up some protestors, and cops and a local pro-Beijing politician were photographed chilling with the gangsters. Outrageous stuff, completely documented at the time, and I knew I was going to have to do something with it eventually. My story takes place ten years later, when this same corrupt politician is hanging out at his vacation home in St Tropez. It’s from that series I’ve been writing for a couple of years now, about this pair of hit men, if that doesn’t spoil the ending for you.”

“I take it things don’t end well for the guy.”

“Hell, no. ‘Hoenggong Jan, gā yáu’ they said at the time; so, yeah, I ‘add the oil’, but in more of a literal sense… along with a match.”

“You aren’t… you know… worried about the parole board having concerns over you writing stories about killing people?”

“Well, that’s the second thing. After getting written up a bunch of times for selling essays, I started using a nom de plume. This way everyone gets to win: the prison gets to imagine they’ve silenced me, and I get to occasionally eat something from the commissary. Being a starving artist may sound great to the edgy, revolutionary, scarf-wearing set, but it actually kind of sucks in reality.”

“That why you are skipping lunch? Got a cabinet full of food now?” Marlow asked, looking at his watch. Do not count the hours, he reminded himself.

“That, and because they are serving ‘Fuck Me Not Again’ today.”

Marlow blinked at the other man. “I never could keep track of all the nicknames and neologisms coming out of the kitchen. That’s beef stew?”

“Tamale pie.”

“Ah,” Marlow sighed. I can pass on that, too, he thought. He wasn’t really hungry. It’s almost over with anyway, this bitching about awful state food. His eyes wandered over his shelves for a few moments, while he sipped his coffee. “Get thee behind me,” he murmured.

“Come again?” Winston asked.

“What you said a minute ago,” he responded, hesitating. “I… myself made an ironic allusion to something biblical this morning when I was talking to Licky. You mentioned hell, too, a subject that seems to be insisting upon itself today. I guess I was just thinking that it’s so strange the way beliefs I gave up on years ago seem to have saturated my lexicon to the extent that, even within my unbelief, liturgical pieties keep popping up. I mean, ‘soul’: it’s the twenty-first century, and I still can’t find a word to replace a term that should have died the second we first fired up a functional MRI machine. Is that my poverty of imagination, or is it something bigger?”

Winston hummed and chewed on the end of his pencil for a moment. “Soul is tricky, I think. I used to play the piano when I was a kid. My mother had a serious crush on Chopin, and she had all of these bright yellow, Schirmer editions of his works. In one, there was this preface to his 11th étude of Opus 25 in A minor by some critic. I can’t recall the author’s name now, which is strange, considering all the hours I wrecked myself on that piece.” He shook his head slightly, then continued. “In the introduction, this guy claimed that ‘small-souled men’ shouldn’t attempt it, no matter how agile their fingers. It was clear what he meant: the piece required a ton of feeling, the ability to ignore the head and allow the music to come from a much deeper place. I don’t need to believe in some magical essence in order to have understood him, and I’m pretty sure that virtually everyone who read the statement understood that he was not talking about some mystical spirit-stuff. And I don’t need to think in those terms when someone like you drops the word in conversation: you simply mean a measure of our capacity for compassion, decency. Your problem is that you are too wrapped up in demanding that the word have metaphysical connotations. It’s that whole god-shaped hole thing. You never really got over all of that childhood programing you went through, and so you’ve never really tried to plug up that lacuna with anything. God’s ghost still haunts you. That usually just makes people sadder, in my experience. You seem to be actually angry about it, like you are blaming God for not existing. That’s kind of weird, you know?”

He’s not wrong about that, Marlow thought. But it doesn’t really matter anymore. Or it doesn’t matter enough to change anything. “I guess I never thought that replacing one fantasy with another solved the original problem, even if it would have made me feel better. No offense,” Marlow said quickly.

Winston smiled. “None taken. I know, in the grand scheme of things, there’s not much daylight between an atheist and a pantheist. In a theocracy, my bonfire would burn right next to yours. But, by believing that nature is in some sense holy, and that I have some relation to eternity by being a part of that holiness, I think the absence of an active, theistic deity stings a bit less.”

“But it’s still fundamentally irrational. ‘God is nature’? ‘God is the universe’? That’s just semantic wordplay. Spinoza may be more intellectually respectable than Christianity these days, but it’s just another set of fairies in the garden.”

“Maybe,” Winston said, slowly nodding. “That might be true. I don’t believe so, but you may be correct. I happen to think that the infinite intelligibility of the universe is a pretty good summation of what I think of as God, but I may be wrong. It might really all be some kind of indeterminate soup down at the bottom. And yet, forgive me, Charles, but at least words like ‘hell’, and references to a passel of Levantine folktales don’t cause me to automatically and dependably fall into a brooding séance of introspection. Whatever l have, it allows me to still connect to joy, purpose, and meaning. When was the last time you were actually happy, up there in the Castle of Reason?”

He doesn’t understand, Marlow thought, taking another sip from his cup. How could he? He’s a thief. He’s here for stealing things. The harm he caused was the loss of material wealth. Granted, it was a lot of material wealth. But still: he nevertheless continues to live in a cosmos where the past might be recoverable, or at least correctable in the future, where redemption remains a real possibility. Like Manos, he too could actually break even with the house. It’s different when you’ve taken a life. You do something like that, you aren’t supposed to ever feel joy again, you aren’t supposed to be able to have dreams. You don’t get to be whole.

“Why not?” Winston asked, his head tilted.

Marlow snapped back to attention. “What?”

“You mumbled, ‘you don’t get to be whole’. Why? Isn’t that the goal of all of this?” he proposed, waving his hand around at the walls; though whether he meant life in general, or the prison and the library in particular, Marlow couldn’t tell.

Because the smell of cordite won’t go away, Marlow nearly said out loud. Not after thirty damned years. Gods I’m tired, he thought, sighing deeply. Instead of saying any of that, he shook his head. “Look at me, I’m saying my thoughts out loud. Rookie move, right?” he laughed a little at himself. “I guess on some level I still wish hell existed. Not as a permanent site; only a sadist and a tyrant would demand eternal punishment for a finite series of trespasses, and only a moral coward and opportunist would follow such a despot. But something like that, some kind of painfully obvious means of equating or connecting transgression and just deserts.”

Winston smiled. “Again, I thought that’s what we were doing here.”

“I don’t really buy that. There are too many divisions or barriers between the act and whatever this is; too many independent factors that got involved, so that the end result seems almost purely arbitrary rather than a consequence of anything. Look, none of these officers know or care about what you or I did to get here. If one of them came in here right now and hit you over the head with a baton, he’d justify it through the language of correction, and he’d get away with it. Society might even give him a medal, a raise. But it wouldn’t have anything to do with that. None of the bullshit we go through here has anything to do with that. It all has to do with the moral failings of the people in charge. There’s no real connection between what I did thirty years ago and what I’m experiencing today. I’m fifty years old. My younger self has been dead for decades. How could this be didactic for society, in any case? My sufferings, or lack thereof, are completely occluded from view.” For some reason, saying that “thirty” number out loud made Marlow want to scream.

Winston stared at him for a long moment, then shook his head, as if he were trying to clear a minor ache. “You are a piece of work, Charles.” He rubbed his hand across his chin for a second, gathering his thoughts. “If I understand the concept of hell, it’s essentially the destination where there is no other place or time to which you would not flee in order to escape it. Like, if you can say, ‘Okay, the torture chamber of the Spanish Inquisition is worse than this’, then you aren’t in hell, because you’d rather be here than there, and hell is always supposed to be the worst place there is. You can’t honestly tell me that you’d like to be taken to the rack by a bunch of god-bitten thugs. How is that didactic?”

“It would make all of this so much simpler. I keep looking for the entity that I can go to and say, ‘Hey, please take more from me. I want to pay what I owe. I want to be complete again, make those I harmed complete’.”

“Oh, Charles,” Winston said, looking at him with a degree of pity that instantly annoyed Marlow. “That person you are looking to address is yourself. Sure, society has to take their pound of flesh, that’s the closest we’ve come to yet in our clumsy pursuit of whatever ‘justice’ really is. But only you get to decide when you’ve learned the moral lesson behind the failure that put you here. The only real forgiveness comes from inside.”

Then may my denial of that be my greatest offering, Marlow thought instantly. This declaration made him feel better in a weird way. He smiled, swallowing the dregs of his cup, while looking into Winston’s to see it empty. “And if we’re both wrong? If we both have a very extended date with some horned and pitchfork wielding masochists in the hereafter?”

Winston remained silent for a moment, then glanced at his watch, and started gathering his papers. “Who ever strives with all his power, we are allowed to save.”

Marlow detected the cadence of a quotation. “What’s that from?”

“Bah. And you call yourself a librarian. Go read that biography on Goethe that you obviously haven’t gotten to yet. They’re only some of the most famous lines in all of German literature.”

“I’ll get to it,” Marlow lied, standing up.

“See you tomorrow,” Winston said, as he left to return to class.

“Sure,” he responded. Marlow then took the two cups down the hall to wash them out in the sink. After he’d returned and replaced them, he moved to one of the shelves in the rear of the library, the one he reserved for books no one ever requested. His forgotten children, he sometimes referred to them. A dark red, hardback volume attracted his attention, and he removed it from the shelf. The cover was worn, a sort of herringbone pattern showing through the crimson. He remembered the day this one had arrived, a few years ago. Just north of center on the cover, a small, black rectangle with Three Soldiers and ‘Dos Passos’ in gold lettering. No ‘John’, just his surname, Marlow thought, marveling at the era when this man was so well-known that no first name was needed. How many people even know who Dos Passos is today? he wondered, flipping open the cover to the title page, with its little colophon of a Greek god. Who was that? Apollo? Winston would have known. He then looked at the publication date: 1932. 1932! The pages were pleasantly browned and dry with age, and had a sweet, spicy aroma that carried just a hint of smoke, like the book had been kept for years in a room where real logs were regularly burned in a fireplace. The events this thing has witnessed, he thought, running his fingers across the pages one last time before replacing it.

Looking to see if Mr Clarke had stirred, Marlow then bent down to a lower shelf and removed René Belbenoit’s Dry Guillotine. Opening it, he saw that the space he’d hollowed out inside still contained a small package, wrapped in brown paper. He closed the book and transferred it to one of the carts, inserting it into the middle of a full row. Satisfied, he moved the carts out of the way, and settled in for the afternoon rush, such as it was. Over the course of the next four hours, convicts straggled in, looking for something to take them away from the prison for a few hours, a few days. In a way, I’m a bit like Manos, Marlow thought at one point: he distills and bottles his solution to the problem of the present, I hand mine out in little rectangular parcels. His business model is more profitable, he admitted. But mine is better.

His last visitor left shortly after 4:30pm. Marlow waited another fifteen minutes, and then went to the door of Mr Clarke’s office and coughed loudly, startling the man out of his siesta.

“Wah? I’m just resting my eyes here,” he said quickly, sitting up. Seeing that it was only Marlow, he relaxed, and then looked at his clock.

“I’ve got two carts for seg and close custody, and then I thought I’d call it a day,” Marlow repeated the familiar closing lines of his daily drama.

“Okie dokie. I think I’ma head over to ODR and get some grub in me. Everything ship-shape?”

“Oh, we’re leaking all over the place, but it’s no worse than normal.”

Clarke laughed. “Aight, then. Till mañana.” He still pronounced the word like “banana”, Marlow thought, even after roughly four thousand attempts at correction. Some things were beyond fixing, he thought. Just like everything else.

Marlow slung his much emptier bag on top of one of the carts, and pushed one ahead of him, while pulling the other behind. Three checkpoints, he assessed; those, and maybe the metal detector near the visitation room, if they were manning it. One last infiltration and I’m out of it. The mesh bag laid out carefully in view on top of the cart should be tempting enough as a target, if they chose to look at anything. Not much I can do about Ms Lopez, he thought, outside of that priming routine I ran on her this morning. She hardly ever looks at me anyways, he reasoned.

He needn’t have worried: hardly anyone paid him a second glance as he moved from one side of the prison to the other. Before he left the second cart outside of T-Wing, he removed a book from the top row and transferred it to his bag. Ms Lopez smiled at him as he returned to his wing. He held up the bag. “Heroin this time, I’m done with the coke.” She rolled her eyes at him and used her keys to open the crash-gate.

Just like that, he thought, as he walked towards the staircase.

Just like that, and the backdoor pops right open.

Now all he had to do was walk through it.

To read Part Two, click here

2 Comments

Cancer for the Cure - Minutes Before Six

December 31, 2023 at 6:00 pm[…] something I’m listening to or reading to Tricia or Kevin. I had the protagonist in “Release” comment that if there was an inverse-square law for guilt, he’d never noticed it: my […]

Release – Part 2 - Minutes Before Six

February 22, 2021 at 6:11 pm[…] To read Part 1, click here […]