My muscles are coiled like a spring. I’ve thought about this day for so long, to actually be here in the bullpen waiting for my chance to speak to them… it feels like a dream. Maybe a nightmare. I consider all the ways the interview could go wrong. What do they want from me? I’ve already given them a quarter-century of my life. I can’t stop my heart from thudding. I have to remind myself to breathe. I have to remember what to say. Or should I forget? Maybe they’ll favor spontaneity. I close my eyes and concentrate on inhaling and exhaling. There’s nothing more I can do.

“A police officer, Jane.”

“An off-duty one, John.”

“Does it make any difference?”

“No, I suppose not. But his record…”

“Yes, his record…”

I close my eyes, hating myself for a moment, then just as suddenly open them and smile. “I know. I know.”

He enters. Shaved head and tattoos, blank face. I don’t know why I even care to note his features. It doesn’t matter. I don’t like it, exactly… but a police officer. It’s a no-brainer. It is what it is. But… they can appeal. And he’s had a lawyer prepare his paperwork. It doesn’t change anything. But we have to be careful. I have to be careful. John’s been doing this for years, and he knows well enough. It’s me. I would never say this to anyone… hell, I can’t even say it to myself. We will afford him the opportunity to share his institutional record, his release plans, give him a chance to demonstrate his remorse. But, a police officer. Not on his first board. Not on my watch. Jesus Christ. Let’s get this over with.

“Hello, Mr. Smith,” I say. “I’m Jane Doe, and I’m one of two parole commissioners here before you today conducting this interview.” I know better than to wait for John to speak. Nothing this inmate has to say today will prompt him to open his mouth. “So, tell us. What happened on the ninth of May, twenty-four years ago?” And the farce begins.

She almost smiles. I examine their body language, desperately looking for cues. The other one, the older-looking man, says nothing. Not even a “good morning.” Fuck him. No… Stay positive, Mike. I try to remember what to say first, but I’m blindsided when, within thirty seconds of sitting down, the woman asks me about that night. Remorse, remorse, remorse. The word has been beaten into my head by my lawyer. I don’t know how I really feel. I was young and stupid, running the streets, high as a kite when I did it. I am sorry, though. But I’m also angry. I can’t change the past. How can I genuinely dredge up feelings of remorse that have been tamped down by twenty-five years behind bars? I wasn’t even the shooter. I didn’t want anyone to die. It was just supposed to be a robbery. But I have try… I have to. Otherwise, these people will let me rot in a cage for the remainder of my life.

“Twenty-four years ago, ma’am, I was a nineteen year-old, a young man.”

And so his tale begins. The usual shit. I was young and impulsive, blah, blah. I listen calmly as he explains, pleads with us, he wants us to know that he wasn’t the shooter, that it wasn’t his intention to kill anyone. True as that may be, a murder committed in the course of a robbery, or any other felony, makes him just as culpable in the eyes of the law. In my eyes? I try not to think about that. My emotions aren’t as clear and uniform as maybe they should be. Certainly, my colleague, John, has no doubts about denying this man his freedom. I harden myself, maintaining eye contact all the while. I probe with questions about his initial unwillingness to tell authorities who his accomplice was. “Rat” is the word they use. But then, I’ve never understood the criminal code of honor, nor do I wish to.

The next part is excruciating. His records are voluminous, with numerous letters of support, even from high-ranking DOCCS officials, including the superintendent of his current facility. He has volunteered and completed every conceivable program that he could. As much as I hate to admit it, he is a model inmate, and his rehabilitative efforts are genuine. But we serve at the pleasure of the governor, and he at the people’s. I wonder if Mike Smith knows how it goes. Well, he’s about to learn. Careful to recite all his achievements (we have to cover our asses, of course), I ask him if he has any final words.

“Mr. and Ms. Chairman of the Board, I thank you for listening to me this morning, and for taking the time to review my institutional record. I have done everything in my power over the last twenty-five years to reform my ways. I understand how serious taking another life is. And I am sorry. If released, I will help at-risk youth so that they do not go down the path I went down. All I ask is that you give me the chance to do that.”

There. There’s nothing more in me. I’m emotionally drained. Of course I’m sorry, but I’m also a lot of other things! I’m growing older, my loved ones are growing older, and there’s absolutely nothing more I can do. I don’t want to be an old man in prison. Please, just give me another chance. Just one more, that’s all I’m asking.

Samuel Hamilton, and what I know of him from reading his appeal in Hamilton v. New York State Div. of Parole, 119 A.D.3d 1268 (2014), inspired this piece, as did my own anxiety about my upcoming first board appearance.

Going through parole cases, it was inevitable that I’d stumble upon Hamilton. I remember in 2014, when I was working in the Clinton Annex law library (before it closed), how this case emotionally impacted me. Nearly a decade later, it still boggles my mind. How can those commissioners have, in good conscience, denied him his freedom. It remains valid case law in the third department in New York State that the parole board can deny someone their freedom SOLELY on the seriousness of their crime.

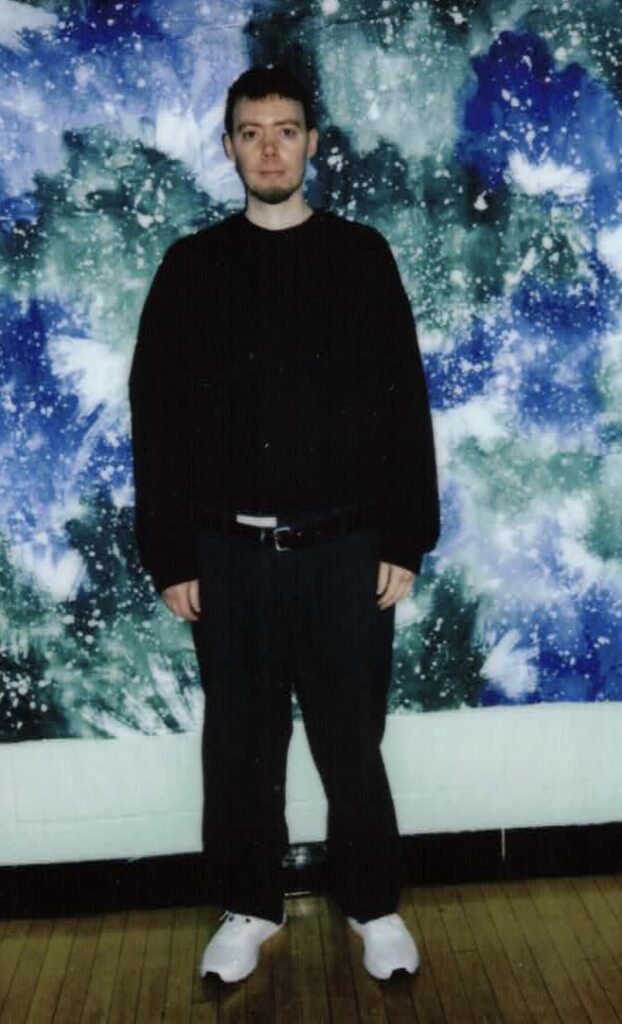

I changed a few things from the actual Hamilton. His physical features, for one–and in the appeal, I read that it was not even his first parole board. Far from it. Of course, I don’t know what the man was thinking or feeling, but it is not hard to imagine. I don’t know what happened to Mr. Hamilton. I assume he was eventually released, but it really begs the question: is the parole board there to resentence an inmate? Or are they forward-looking?

Last thing: if you want to support a worthwhile criminal-justice cause in New York State, RAPP (Release Aging People in Prison) is worth considering. Changes have been made to New York State parole laws in the last decade or so, but more needs to be done.

No Comments