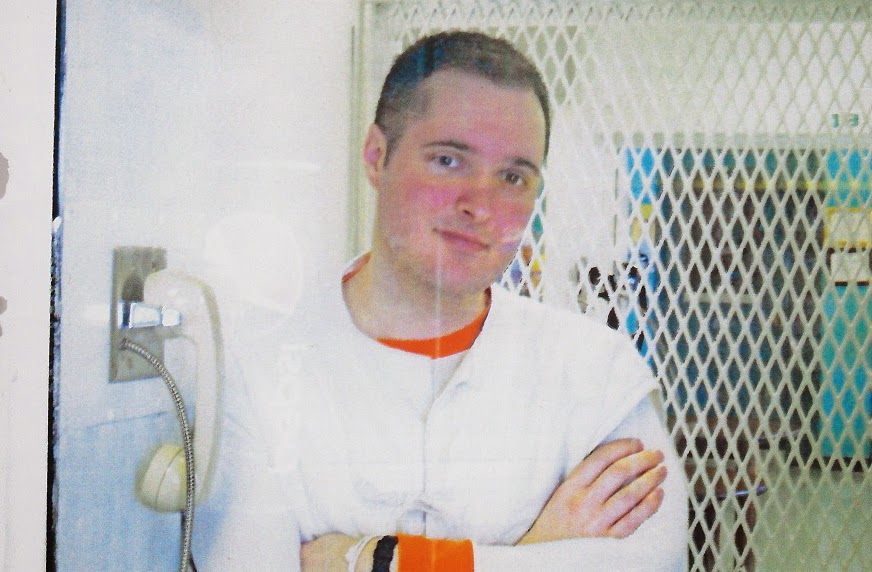

By Thomas Bartlett Whitaker

To read Part 16, click here

The specter of the shantytown in Monterrey stalked me as I rode the bus back to Cerralvo. For roughly nine months I had been spasmodically bouncing across the emotional spectrum from near-manic restlessness to an almost total enervation; what I had witnessed settled me down finally into a position of gray hollowness. When my Buddhist friends talk about “non-attachment,” I get it: it was my natural state, at least for a while there. There are those that damned me for my “coldness,” and maybe they were right to do so. I don´t know. I can only say that there are times in life where not feeling anything is the only available survival strategy.

Upon returning to my new home in the taller, I sat in Emilio´s workshop for a few hours, simply staring at his workbench and tools. If life were a chess game, you could say that I was in zugzwang, all potential moves to my disadvantage. I eventually got up and continued cleaning for a bit. The place still smelled like a refinery. The spiders were sending scouts back into the place, and I killed as many of them as I could find. I was not very successful, as I felt many of them crawl over me in my cot after I went to bed. At first I swatted them off, but eventually I became so tired that I just left them alone. They mostly followed suit.

Blackie found me the next day, and his master was not far behind him. A few weeks prior to the Hammer´s fucked-up little loyalty test, I had purchased a package of three notebooks from the local Mercado. I had never cared much about writing before, but I felt myself strangely attracted to the idea that since I had no one with whom to converse, I had better talk to myself if I wanted to continue having a coherent self to talk to. Mostly I wrote letters to people from my past life. I never intended to send them, and always ended up burning them every few days. Sometimes I would wake up in the morning to find that I had simply covered a few pages with “I´m sorry” or other similar lamentations. It was all very melodramatic, and I have no doubt that if I were to view these notebooks today, they would appear mad to me.

I was working on one of these diary entries around 2 p.m. the day after my return from Monterrey when Blackie came loping around the side of the taller, heading towards town. He didn´t notice me sitting in the shade with my back against the wall, but his head snapped up when I called out to him. His befuddled “wha?” expression morphed into doggie joy when he noticed me, and he came bounding over. He was so happy to see me that he inhaled the last half of the hamburger I had left sitting next to me, in a move so swift and practiced that I barely noticed it. Blackie didn´t put a lot of faith in chewing things, exactly. His philosophy was more in line with swallow first, ask questions never.

“Oh, sure, eat my food, you Judas. Where were you the other night when I needed you?” By way of apologizing he stuffed his snout into my glass and slurped up the dregs of my soda.

Not fifteen minutes later the Hammer came walking around the same corner of the taller. Blackie was laid out next to me, his huge rock head resting on my thigh. His thick rope of a tail beat the soil a few times when Papa Ramos came into sight, but he didn’t bother to rise. Neither did I, so the three of us just sat there for a moment. I should have felt something, but I was just too tired.

“You followed your dog,” I finally commented, stating the obvious.

The Hammer shrugged. “I see heem come this way, yes, but I alredy know you ees here. No ees like you move to Argentina, Rudy. You ees right across the road from my ranch.”

I shrugged back, and continued rubbing Blackie behind one ear. The Hammer sat in the shade, on top of what remained of a small wall that once separated the taller´s outdoor work area from the field by the outhouse. He seemed a little tense, uncomfortable even. “You understand why I do what I do?”

I spent a few seconds analyzing the implications of his question. Finally, I nodded. “I do.” I did, too, in a weird way. He had let me into his life based on bad information from his son, and had tried to save the situation by using me in Aldama for one of his little games. Later, he began to worry that I might not bear up under pressure, so he had to test me a little. I got it. I wish that I didn´t, but he hadn´t survived this long in the narco-game by taking things for granted.

I seemed to be swimming in a thick river of calm, just drifting along, watching the world on the banks pass me by. An author I read as a young man called this state “the zero,” which seems rather apt. It´s always seemed remarkably strange to me that you can pretty much do anything when you take the “you” out of the equation.

Looking at this pint-size gangster with his huge ears and protean, impossible-to-pin-down personality, a large portion of whatever was manning the bridge wanted the Hammer to just shoot me and be and be done with this farce.

“We need to be clear about a few things. You need to understand that I´m not going to be involved in your business, family, gang, cartel, or whatever you want to call it. I mean really, really understand. Not one of your ´I´m pretending to listen to you, but I´m really already seven moves ahead of you and you are already involved´ sorts of things. You want me to build your ranch. Fine. Clean your stables? Also fine. I don´t think I have much left in the way of pride, so whatever shitty job you can imagine for me, just tell me and I´ll do it. But I won´t play those other games. You saw my face. I´d have shot those guys, if the gun hadn´t been loaded with blanks. I understand why you did what you did, and you got the answer you wanted. Understand that ´can do´ and ´will do´ are not the same thing. Do you understand this?”

He started to talk but I held up my hand, the empty place in my heart giving me strength.

“You’ve shown me two faces during my time here. I know they are both true. Most people would not be able to understand how this could be, but most people didn´t have my childhood. I am appealing to the part of you that has shown me great kindness, the one that paid six figures so that Lucía´s parents could get pregnant, the one that subsidizes every branch of your family tree. The one that even agreed to take me on, because we both know that if this had been pure business, you´d have stuck me in another town, far away from your children. I´ve been mulling this over for a few months, and there is no way to explain your kindness unless you genuinely felt some compassion for me. You´ve been an illegal in a foreign country, so maybe this is why. I thank you for what you have done, but if I have worn out my welcome, just get me the ID you promised and I´ll be gone. If you´d rather I stay – which is my preference because I´m really too tired to care about tradecraft right now – I really need for you to understand all that I have said, for this to be crystal clear.”

The Hammer sat there for a moment, just staring at me. He picked a speck off his shirt, and then stood up and walked into the open back door of the taller. I could hear him walking around inside.

“Come back to the ranchito. Thees place is no good,” he said a few minutes later, standing in the doorway, looking out upon the unpainted gray walls of the adjacent buildings.

“Gelo, please answer me.”

He sighed. “I begeen to theenk you nickname is to be ´El Mula´, you ees so stubborn.”

“Gelo.”

“Yes, yes, I understand. You really want to leev here? Ees a dump.”

I nodded. “It could use a few things. A chest or dresser maybe. A fan, definitely.”

“Let´s go get these theengs. My treat.”

I held up my hand again, sort of enamored it its newfound power to silence this man. “No.”

“¿Por qué?”

I thought about it for another moment, before answering.

“Turkeys. Pavos,” I continued, seeing the blank look on his face. It didn´t go away even after switching to Spanish. “Pavos, hombre. For a turkey, every day is really grand. They have this nice human that keeps feeding them, protecting them. It´s safe and warm in this building he provides. Until Thanksgiving. You know Thanksgiving?”

He nodded. “Sí, sí. Indios. White people. Eat together before they keel each other.”

I closed my eyes for a moment, about to correct him, before realizing that he was pretty much right. “Uh…yeah, so then comes Thanksgiving. All a turkey´s experience and knowledge actually works against its chances of survival.”

“I no going to eat you, Rudy. You no have enough meat on you bones.”

“The point is, you have enough dependents, and I´m starting to think I have allergy to dependence.”

He looked around for a moment. “You plan to carry a dresser on you back all the way from town?”

“Um…no,” I admitted.

“Then get een the maldita truck. ´Do you understand?´” he mimicked, causing me to wince. I hope I didn´t sound half as patronizing as his copy, but people who patronize as a habit seldom notice it themselves.

Both the furniture stores in town were owned by the same man, Don Hector. I wasn´t expecting much, but the main branch turned out to be a huge multi-story warehouse filled with at least several hundred thousand dollars´ worth of product. Don Hector had nearly everything, from mattresses to couches to ovens.

When the Hammer and I first entered the store, a short, plump woman with a guileless smile muted the television and stood up to greet us. To her left sat a young woman with a punky sort of hairdo, who was busy jamming her fingers down on her cell phone. She didn´t unglue her eyes from the screen until her mother commanded her to fetch her father. Even then, she hardly looked up. I have no idea how she managed to maneuver her way through the storeroom without tripping over a couch or footstool.

The señora seemed to know who Gelo was – no surprise – and treated him with a sort of servility that made me uncomfortable. I was introduced as Gelo´s “American son” yet again, a claim which was repeated when the stern and corpulent Hector arrived from the back office. While the señora seemed to believe the tale and welcomed me warmly, Hector’s calculating glance told me he was not entirely taken in. No fool, this man, I remember thinking to myself.

I had already mentally rehearsed the Spanish for the items I was looking for, and I was satisfied when my “father” raised his eyebrow at my improved linguistic skills. With the air of a practiced salesman, Don Hector quickly guided me through his wares, selling me a 20-inch television, a small chest of drawers, a massive fan the blade of which looked like it had once done duty on a spitfire, and a small refrigerator that I didn´t need until he convinced me I needed it. This last item was warehoused on the second floor, adjacent to a section of wall that was sealed off with a blue tarp. I didn´t understand every word that passed between the Hammer and Hector, but the latter appeared to be complaining that the work crew he hired to amplify the back end of the store had taken off for three weeks to complete the “maestro´s” new house. The Hammer clearly enjoyed telling Hector that I was working on his ranch for free. Hector seemed surprised; I guess he thought that Americans didn´t deign to do manual labor and jokingly asked what I charged per hour. The two elders had a good laugh that seemed fake to me, and I couldn´t tell whether the joke was somehow at my expense.

On the way back to my new digs, the Hammer popped me on the arm, and smiled at me from ear to ear. “You perro! How you say ´astuto´ or ´taimado´? Sneaky?”

“Uh…sly, maybe?”

“Eso es! You sly dog. I theenk you is a cold feesh but now I see you is muy táctico.”

I was completely befuddled. “The fuck are you talking about?” It was strange, seeing him like this. He seemed to have dropped about thirty years in tens seconds.

“Cynthia! La hija del Don Hector. Thees girl, she no like anybody. She punch Edgar once for trying to kees her, but she stare at you the whole time we in the store.”

“The girl with the phone? She never even looked at me once.”

“No, no, I see. You too busy counting the beel. But I watch, I see.” He pointed one finger to bottom of his left eye.

“Gelo, listen to me. When it comes to women, maybe you see what you want to see. I mean, you have about fifty kids.”

“Okay, I take eet back. You is cold feesh. But you should marry thees girl. Don Hector tiene un chingo de lana.” To this he held up his hands in the Mexican gesture for a fat wad of cash. “You marry her, I going to put puros colchones por toda la casa. Mattresses as far as you can see”

“I think she´d be more likely to marry her Nokia.”

“Rudy, you ees the dumbest smart person I ever meet. The dumbest smart turkey.”

I thought about it for a moment. “I think I am going to have that printed on my business cards.” He sighed, and let the matter drop.

The new furniture made my little nook livable. The television only picked up a handful of channels, but one of them had subtitles in English, so I could watch cheesy novelas and see the English translation below. I came to realize very quickly that these translations were somewhat less accurate than one might have wished, but it did help. Nearly every day I fell asleep feeling like my head was a basin overflowing with new terms.

The novelas made me feel very strange. They were almost exclusively dedicated to chronicling the lives of some obscenely rich nitwits. I couldn´t understand why a nation made up almost entirely of the Third Estate would choose to slavishly follow stories of the Second. Didn´t they understand that it was only their attention and admiration that made these imbeciles rich in the first place? Didn´t they understand that these shows were cultural programming, keeping them distracted and entertained so that these very cretins could rob their country blind? The shows didn´t make me want to be rich. Mostly they made me want to punch these jackasses so they would just shut up.

My days devolved into a pattern of watching trashy soap operas, eating and sleeping. I would occasionally clean and re-clean Emilio´s workspace, and beat back the still advancing arachnid battalions. On a few occasions I went to the ranch to work on the block walls, but I always felt like it was time to go after a few hours. I seemed to be on relatively stable footing with the Hammer, but how could I really know? Whatever he said, whatever face he showed, I felt like the dumbest dumb person in the world, a mere baseline human involved in the games of gods who were dealing plays I couldn´t even see, let alone figure out.

Edgar showed up a few times to drag me back into the world of the living. The kid had a good heart. He could see I wasn´t in a great place and wanted to cheer me up, but his version of fun seemed tedious: the same “vueltas” around town, the same catcalls to the same girls, the same Coronas on ice. The truth is I didn´t want to feel better, I think. That part of my brain seemed dead; grief makes you feel like a stranger to yourself. On several of these little forays Edgar got really excited and pointed to a group of girls, among whom Cynthia would always be present. I have no idea how he could pick a single girl out of a crowd of hundreds; his radar was astounding. He would always hit my arm, and make a goofy “eh? eh?” noise. It pissed me off that the Hammer was telling people about his stupid theories. She never looked my way anyways, and I berated myself for even thinking about such things. Everyone here seemed to know each other so well that I felt like a threefold stranger, and in any case, I´d had a good woman once and it made no sense to go looking for yet another when my track record was so abysmal. Who hasn´t been scarred by love, I remember thinking, and dismissed Edgar´s incessant hormonally-inspired quests.

A few days later both the Hammer and Edgar caught me at the ranch. I had just set some tile in one of the more completed cabin rooms, and was admiring my handiwork when Edgar´s Ford Ranger pulled up into the shade of the mesquite trees. Gelo unloaded a crate from the back of the bed, and presented to me his newest fighting rooster. It looked and smelled like all the rest, so I wasn´t really able to see what he was so excited about. Edgar was feeding off his father´s rare good mood, and started telling me about some party he was going to. I just wanted to clean up my mess and get the mezcla off my hands and clothes. He kept poking me in the side, and when I turned to swat his hands away he grabbed them and started dancing with me. I punched him and he fell back, goofily rubbing his bicep.

“Gelo, what the devil is he going on about?”

“There is beeg party tonight. Es la quinceañera for Don Felipe´s daughter. He a beeg man in the PEMEX, has beeg office in Cadereyta. But some of us know how he really got the moneys to start hees beesness. Will be many peoples there. You must go.”

“I ´must´go’? I´m not really big on parties.”

“Leesten,” he said, setting down his fancy chicken, which began strutting about the place. “Party like thees, ees a time to show un poco de respeto. You come for a few minute, maybe dreenk a leetle, maybe dance a leetle, then you can go. Try to have a leetle fun, yes? You know thees word?”

“You are going?”

“Ah, diablos, no.”

“Then why – “

“Because Don Felipe, he show the respect to me. You show me respect by going. Everyone want to meet my new son,” he snickered at this last.

“Um…okay. I´m not drinking his booze, though. Ten minutes, and I´m gone.”

“Dreenk, no dreenk, me vale madre.” He turned to see where Edgar had gone, before reaching into his shirt pocket and removing a small glass vial. “Take thees, have some fun, cold feesh dumb turkey. If you no leev a leetle, people is going to think you is some sort of pistolero, me entiendes? You have to act the part a beet.”

I looked at the vial in the sunlight. Inside was a packed matte, off-white looking powder. It wasn´t my first time to have such a vial in my hands.

“This is an eighth?”

“Un poco más, about four gram.”

“Uh…thanks,” I said, tucking the vial into my jeans pocket. I had no intention of taking any, but if he wanted to toss a couple hundred bucks my way, my poverty wasn´t going to dissuade him. I made sure that Edgar understood that I would find my own way to the shindig, and not to come pick me up. The last thing I wanted was to be dragged to the civic center two hours before the thing even started.

I could feel the party in the air two blocks away, a low rumbling of competing bass lines. I could feel something else, too, a rising sense that I was going to regret this, that I should turn around and just leave. This was dumb. The streets leading to the civic center were packed, and I couldn´t help but notice how many of the cars had Texas plates. I pulled my vaquero hat lower over my brow. Brightly colored flowers adorned the doors, and scores of teenagers hung around outside, sneaking furtive sips from styrofoam cups. The lights inside were nearly blinding, and I almost didn´t see the girl who bounded up to me with a lei and attempted to wrap it over my head. It was my reflexes more than conscious thought that caught her hands, and her smile faltered as I lightly pushed them away. Her daybreak eyes clouded up in confusion, and it didn´t take much imagination to see why. She was maybe twenty or twenty-one, about as fine a woman as a man could imagine, wearing a tight little nothing of a dress that had more to do with semiotics than fabric. I doubt she´d ever been turned down by a man before. I left her standing at the door and went to the bar. Bottles of El Presidente brandy and Hornitos Tequila lines the circular tables across the room, and an equal number sat within grasp up and down the bar. My decision not to drink evaporated and I poured several ounces of tequila into a glass, tossing it back. Thus fortified, I tried to take in the room.

The space itself was a rectangle roughly seventy meters wide and maybe ninety meters long. The center was reserved for the dancers, of which there were at least seventy or eighty at any given time. Despite the place being decorated with a Hawaiian theme, the deejay in the corner was playing pure Norteño music. Hundreds of revelers lined the walls and sat at the tables, talking over the music. After a time I saw Edgar and some of his cronies. They were trying hard not to transmit the fact that they were stone drunk, and failing marvelously. I noticed other people I had seen around town, too, but who remained unintroduced. I had waited until around 9 p.m. to show up, and everyone seemed to be really enjoying themselves.

I began to see other men, though, static points almost completely lost in the constant movement. These men were not physically of a type; some were fat, others thin. Some word modern style of clothing, others dressed like the Hammer. They all seemed to sit with their backs to a wall or to another of their kind. They smiled, drank, and laughed, but none of them danced and none of them ceased to scan the room. It looked casual, but the more I watched, the less it so seemed. I also started to notice how when they refilled their cups, they barely added any liquor, for all the show. This is one of the most potent memories I have of my time in Mexico; it comes to me unbidden at times when someone brings up the narco-war: a room full of beautiful, smiling, decent people, all taking pleasure in each other and their world, even as the monsters lay hidden in their midst, smiling at their inattentional blindness. One of these men was sitting at a table next to what I presume was his wife and two children. She was talking to him, and he calmly looked down into his lap. I could see the blue glare of a cellular phone reflect off the planes of his glasses. He stared at it for a moment, before he flipped it closed and brought his cup to his lips. Over its edge, he scanned the room as he fake-sipped, coming at last to me. We stared at each other for a long three or four seconds, until he tipped his glass to me.

Had he seen me at Aldama? Did he really think I was the Hammer´s son? Was that the acknowledgement a man gives another man, or a monster a monster? I turned my back on the room. Two men to my right were conversing in rapid-fire, completely fluent English. The thought returned to me that this was stupid, stupid, stupid. I noticed that behind the bar area stood the wide entrance to the kitchen. A steady stream of waiters had been lugging heavy trays in and out of this space since I had arrived. I knew there would be an exit in the kitchen, so I grabbed my bottle of tequila and walked towards the well-known din of kitchen sounds. A few turns and one or two surprised faces later and I was walking out the back door of the center. A low retention wall ran parallel to the building for fifty or sixty feet on this side, and I sat down on it. From here I could see a portion of the dance floor through one of the windows. People spun by and were gone, only to return again minutes later. I took a long pull from the bottle.

Some people just fit in. They just understand the right thing to say at the right time to the right people. Some of us watch from a distance, trying to take the algorithm apart to see how it works; when we reassemble it and deploy it, the thing breaks to pieces in our hands. You´ve got all this deep-level programming that tells you it is vitally important that you find some in-group, some place where the dumb shit you do won´t count against you quite so much. People that laugh with you, not at you, and have your back if someone moves against you. You had a touch of this when you were young, before culture and genes taught your peers that your differences made you the competition, made you a target, something to be excised. The quickness with which your no-longer-friends turned their backs on you for one reason or another is astounding, and you never find replacements or even regain your footing. For years, everywhere you go is enemy territory, every person you meet someone who will ignore you or worse. The worst part is, no matter how many times this happens, no matter how many times you are rejected, you do it to yourself. You let them hurt you, because every single time, you leave open the possibility that this person might be the one to do otherwise.

So you change. You flip through permutations of yourself so fast that you can barely keep up, until, magically, some random iteration clicks and a few people start to notice you. Oh, you know it´s not exactly you they are seeing, not the real you, but who cares because the real you was crap anyways, and on some deep level beyond reason you know, just know, that nearly everyone is faking it, too, all the time. You conclude that acceptance and even love of a false you is better than rejection of the real you, and before long you are so confused about what “real” even means that it ceases to bother you overmuch. And then you wake up years later in a pool of your own blood and it all comes back to you and you can´t face it so you just run, run until you run out of energy at the tail end of a civic center in the backwater mountains of Mexico, a bottle of mid-grade tequila in your hand and an emotional landscape inside that looks like the Atacama. And you feel nothing, nothing at all, and all things considered, you know this isn´t the worst that could happen.

You walk. The desert greets you, embraces you. It doesn´t judge you. It just wants to kill you. It´s not personal. The bottle in your hand has never seemed like a reasonable escape, but you drink from it anyway, because what good have your beliefs ever done you? And it´s there, and presence matters so damned much. It´s gone eventually, and you know on some level that you must have spilled some because there is no frigging way that you just drank a fifth of tequila by yourself. You sit on a large stone and in the distance the lights of Cerralvo compete against the empty sky. The sky was winning, it deserved to win, things are just as they are supposed to be. You remove the glass vial from your pocket, the vial of cocaine that you didn´t remember transferring from your work jeans to these, but hey, there it is and presence matters so damned much. You can tell the stuff is good just by the way it crumbles under the pressure of your fake-real ID. You pause a moment, hundred dollar bill rolled into a straw, to blearily view the situation. There is something hilarious about snorting this cocaine with this bill off the surface of this empty bottle in the middle of this desert. You laugh, and the dope blows away into the night on the out-breath. No matter. You have plenty, and it is good, it´s great. Greatgreatgreat.

The coke beats back the torpor of the booze for a while, so you walk. The desert is yours. You´ve been running through it for months now, you know it´s tricks. Once a cat that seemed to be about the size of a tiger but which in reality was probably just an ocelot rears up in the dark and takes flight, and you laugh and throw the bottle at it, shouting “say hello to my little friend!” You start laughing again and then cannot stop, until you fall onto your knees and suddenly you are screaming at everything, but mostly at yourself.

You don´t know when you pass out, but you do know it when you are pulled from that nothing. It is still dark. At first you can´t figure out where you are, or what it is that is frantically pulling on your jeans. You hear a growl and half-recall the ambushing coyotes, and you kick out fuzzily, connecting with nothing. You think to reach for your knife but your hands don´t seem to be up to obeying orders and that´s when you hear a whine and a familiar snuffling noise. You roll over and Blackie is trying to push you around with his snout. All you want to do is evaporate again so you grab him and tell him to settle the fuck down. You fall asleep to him licking your hand.

When you wake up, he´s still there, laying at your side, and now the sun is up and your head feels exactly like it ought to. It takes you an hour longer than it should have, but you eventually stumble back to the ranch and sit down in your clothes in the shower, letting cold well water pour over you. You take a palm full of Tylenol from the cabinet and walk back to your miserable little rat hole. You want to sleep but you also know that there is something else you have to do, something that you realized in your half-delirious state the night before, something that you´ve been pondering all morning. On some level, you know that it’s wrong, that it is yet another thing you are going to be damned for eventually, but, fuck it, that account is already so far into the red that it´s never going to be squared so you just do the thing because survival isn´t mandatory and no one else is going to do it for you. Consequences only matter if you are still alive to have to deal with them.

He was alone when I pulled my bicycle up to the storefront. I was actually hoping Cynthia might be present just in case the Hammer saw things more clearly than I did.

“What you said yesterday, about what I´d charge an hour? Were you serious?”

Don Hector spoke no English, but my Spanish was now good enough to be mostly understood. He pursed his lips for a moment, thinking.

“You know how to work?”

“I can lay block, brick, tile, I can weld, do basic electrical work like wall sockets. I´ve never tried to do plumbing work but I can learn. I can square your books and run numbers, if you want me to.”

“I cannot pay American wages.”

“I´ll take Mexican ones.”

“Then, you can start on Monday.”

And I did. Because presence just matters so damned much.

|

| Thomas Whitaker 999522 Polunsky Unit 3872 FM 350 South Livingston, TX 77351 |

No Comments

Pearls

October 2, 2018 at 6:44 pmYour story sounds more like a movie,it's almost unbelievable. its scary and interesting at the same time.