To read Chapter 20, click here

There’s nothing like an ending to reveal the incompleteness of things. The Hammer sent me into the shadow of the mountain to disappear, but when I think back over the course of my life, my months there stand out to me like a beacon, an immense barricade that divides the two halves of my existence. What came before often seems to me to belong to someone else, as if I were reading the memories of a character in a book. When I tried to discuss this with someone a few years ago, I couldn’t figure out how to explain this, because nothing immense happened, certainly no catharsis or epiphany that I can recall. I’m tempted to simply say that I matured at a rapid rate there, that I was a child becoming a man, or, somewhat more poetically, that I had been blind but was now starting to see. These are the things we say when we don’t really have any idea what we are talking about, when we need to gloss over events that are far too subterranean for easy explanations. I think, on some level, the difference seems to spin on the axle of my relationship towards pain, fear, and the gradual evaporation of my expectations for what life was supposed to be about. On some level, prior to my time there in the forest, I had believed my life to be some sort of story worth reading; that, in the end, things would somehow come out right. I couldn’t have put it into words at the time, but it was there in the cabin that I first started to realize that there wasn’t going to be any agnorisis or character arc that would ultimately open the book of Meaning for me, that I was not a character in a story and that there were likely never any happy endings. The emptiness of the skies began to trouble me less, and suffering became something that didn’t need to be feared quite so much. Since it seemed that this was to be my lot, I resolved that one of my new tasks had to be the development of a character worthy of this suffering. I remembered the words of my hallucinogenic alter ego about pain, and started to wonder what life would be like if I attempted to apply this as a truth, rather than some sort of witty maxim that I tossed out at parties.

Silence invaded me. I stood outside at night and watched the skies, allowing the wind to rip my comfort to shreds. I traced the keloid braille of the bullet wound on my arm and let my thoughts skim about the periphery of the things I had once believed I understood. Grief makes you a stranger to yourself, and I was frightened by how little I seemed to understand about my own actions. It seemed to me then that I understood nothing about the world or my place in it, that any such claims were doomed by a sort of Icaran vanity to fall and break on the cold surface of these mountains. We’re all of us just lost little fools, I said aloud one night, and the wind seemed to agree with me.

There are times now when startle awake from months or years trapped in the fever-dream of ideology or belief and I can’t do anything but shake my head at my hopeless heart, still crawling about for a Reason for it all. In these moments, I often feel I was at the pinnacle of my wisdom there on the mountain. There was less confusion, somehow. Everything fit in its place because everything was fundamentally without value- things just were. Why was masturbation.

In the mornings I played the lumberjack, felling Douglass-fir and pinion pine. I strung rabbit snares, more for the experience than out of any real hope for protein. In the afternoons I roved, pathless on all of the paths I found winding through that mad wasteland, hundreds upon hundreds of kilometers through ravine and gulley. Reckless days of reckoning were headed my way and for the first time I completely accepted this fact. I won’t say that I welcomed them – that would come later, when I would start to dream my way out of the abyss. But I knew this suffering was in my future. I could feel it as sure as the rain falling from the leaves.

It wasn’t long before I found the Chivero’s homestead. I came across it late one evening, a small, wandering, random sort of cottage surrounded by a series of immense pens and barns. For a moment I interrogated my sanity, because I was certain that I had passed through this section of the ravine before. I sat and looked down on the compound as the sun hid itself behind an elaborate geometric mandala of peaks. At one point I saw Juan move from a low-lying barn to an enclosure, lugging a heavy pail of something. Several small girls of indeterminate age left the main habitation a few minutes later, and busied themselves with myriad domestic tasks that were foreign to me, before finally seeking their father out. I watched them play around with a small pack of dogs, and suddenly it struck me how creepy my actions were. I didn’t want Juan to know I was there, so I settled back against the stone, feeling the cold seep through my sweaters. A fire in the dwelling soon became the most visible point in the world, slowly converting the mustard curtain hanging over a window into a glowing, irradiated shade of Van Gogh yellow. Juan and the girls returned home. I waited fifteen minutes and left.

It rained too heavily the next day for me to venture out. The whole world shifted to gray when I opened the door to stand in the wet soil. I felt a sudden desire for something that I couldn’t name…beauty, perhaps? Can a person desire beauty as one would something to drink? It’s the closest thing I can come to naming. Whatever it was, I fiended for it and then instantly felt ashamed for this need. “What is the quest for beauty if not another form of greed?” I said aloud, and received no answer. Everything felt weirdly liminal, transient – perfect. I closed the door behind me.

The rain slackened the next day and completely tapered off by the afternoon. I took a short stroll and was shocked to find that one of my snares had been tripped. A small gray hare of perhaps five pounds lay in its grip, its neck clearly snapped. I felt yet another strange confluence of contradictory emotions as I dropped to my knees and reached out to touch it. It was winter-thin and dirty. I had no idea how it had survived in such a frigid climate. It seemed somehow obscene that it should outlast fox and owl only to die at my hands. I felt my eyes tearing as I picked it up and released its body from the trap. I began carrying it back to the cabin before turning and returning to the snare. I broke this into pieces and then spent half an hour moving from snare to snare, destroying each.

I had no idea how to dress a rabbit. I still don’t, and I made a total mess of it. I found myself apologizing to it for being such an awful carnivore. A gory two hours later found me staring at a disturbingly small pile of edible meat. I couldn’t believe how little there had been. I had more or less lost my appetite, but I felt like I had to eat what I had killed, or its death would have been completely pointless. I remembered Bilbo Baggins having made rabbit stew in The Hobbit, so that is what I did. Afterwards, there were little globules of fat smeared along the blade of the knife that I had used. They were surprisingly stubborn when I tried to wipe them away. I think it would be good for our species if everyone had to clean such a blade at least once in their lives. It…does something to you.

January slid into February on sheets of ice, sleet, and snow. Juan paid me a visit at least twice a week, and we continued our ritual of mezcal and very little chitchat. He had his own way of incommunicating that might have confused me or even irritated me once, but as the silence settled into my bones more and more, I felt less impressed than ever with words. Juan was essentially indifferent to all of the negative events that befall human beings during the normal course of existence. I couldn’t figure out for the longest time how he could be so immune to anger or a sense of unfairness, and when I tried to talk to him about this he just shrugged. I’m not sure he even understood the question. Life was hard. It was all he had ever known, all he had ever heard about, so feeling a sense of unfairness was simply foreign to him. In his silence he seemed to be saying that fairness is just what we call it when we get what we want, unfairness what we complain about when we don’t.

After the third or fourth visit he began to demand use of “la maquina.” He had arrived the time before while I was listening to my iPod, and initially thought the little white things stuck in my ears to be ear protection. He gave me a skeptical look when I put one in his ear and then jumped straight up when the song started playing. I couldn’t believe it, but he swore this was the first time he’d ever known of the existence of ear buds. It took me awhile to find anything he liked. For a guy living without music, he was awfully picky. Heavy metal was definitely not to his taste- ditto with jazz, classical, and anything EDM. He tolerated the blues, giving me the universally understood hand signal for “so-so.” The best I could do for him was some Spanish pop by Enrique Bunbury and a few mariachi songs that I had loaded in an attempt to figure out how to play them with Cynthia. These latter he adored. I explained to him about the limited battery, so each time he showed up we would listen to four songs. I swear the man floated when he heard something he enjoyed, his smile wide and his eyes closed.

If there was one subject that turned him loquacious it was his animals. He had names for every last sheep and goat. Juan had a rather pronounced overbite. I’d not noticed it before, because it was most noticeable when he spoke sentences longer than a few words. It sort of made him look like he was chewing on his diction and finding it less than tasty. It made him look a little like one of the dogs that accompanied him on his rounds, a mangy, tired-looking thing that stared about mournfully. I nearly choked on laughter the first time I reached down to scratch him behind the ears, because he closed his eyes in the exact same way as Juan did when he was lost in harmonic rapture. I had the strangest feeling that if I poked the dog on the shoulder, Juan would rub his own. Juan taught me more than I ever needed or wanted to know about sheep. Like, for instance, that they snore.

“Que tonterias me dices,” I scoffed, passing him the bottle. “Eso es completamente absurdo.”

“No, no, you will see. I show you. You come to my place, we can eat. Only my wife is louder.”

His offer surprised me. It initially crossed my mind that inviting random narcos home for dinner was probably not a particularly intelligent or successful survival strategy. Later, I decided that in this messed up fiscal climate, that is probably exactly what it was. I thought that he might feel insulted if I said no, but I wasn’t sure that I really wanted to go. I had the idea that witnessing the poverty of his existence was going to wound me, and I felt like perhaps it would be better for the both of us if our lives remained separate. In the end his face seemed so eager that I couldn’t say no, on the condition that I was allowed to send some grub with him. He initially resisted this, but I was able to sway him by staring at him directly and telling him that he was going to take some food with him. He caved instantly, and I got a small taste of what it must be like to live in Ge1o’s world. I invited him into the cabin and let him load up one of the mesh bags with items that caught his eye. I was way ahead of my 80-day plan on food conservation, so I wasn’t worried about the loss, and it made me feel slightly less contaminated for having used a power I detested.

He waved both hands in front of him frantically when I handed him an unopened bottle of booze. “The wife,” he sighed. “Me gusta dar un beso a la botella de vez en cuando, pero mi mujer se lo opone.” I shrugged and put the bottle on the table.

“It’s here when you want it.”

He told me he’d be back the next day and we could walk to his place together. I didn’t tell him I already knew how to get there.

The next morning I braved the icy stream of well water that passed for a shower and tried to scrub the dirt and sweat off my skin. My beard had grown to fairly epic proportions by this point. It itched like an army of tiny insects was doing calisthenics up and down my face, but even so I still wished I had brought a mirror so I could see what I looked like as a woodsman. At night I could get a poor reflected image off of the surface of the windows, but it wasn’t very satisfactory. In those fire lit half visions, it always looked like some sort of small woodland critter had my throat locked in a death grip, which I hoped wasn’t accurate but probably was. As the day wore on, I began to dread more and more the trip to Juan’s. When I was younger, my father would take Christmas presents to the children of some of the employees of Bartlett Masonry, the construction company that my maternal grandfather started. I always felt very uncomfortable witnessing the dynamics of these events. The families were obviously grateful, but I always wondered if behind their smiles they didn’t hate us just a little, there in our Sunday best, deigning to grace their poverty with our benevolence. Did the fathers wonder why they weren’t paid more, if we apparently had so much in excess that we could bring toys? What did the children think? Did they wonder why they had to share a bedroom with multiple siblings, when I had my own? Did they know that I always had a jacket in winter and food on the table? Were they able to see the limited nature of their horizons, when mine were so expansive? Did they sit awake at nights and wonder about why there should be so much inequality in a country supposedly blessed by an omniscient, omnipotent, omnibenevolent deity that claimed to favor the poor and meek? I certainly did, so I’m certain they did, as well. I’ve never known how to explain to people the deep, lingering sense of unworthiness that is at the core of my self, why I’ve always wanted to hug people like Juan and whisper to them that it was okay to hate me for blessings unearned, that I hated myself for them, too. I remember in 10th grade history the disgust and condescension displayed by my peers when we discussed the two revolutions that took place in 1917 in Russia. The rage of the peasants, the violence showed to the gentry and the surviving Romanovs – none of it shocked me at all. I recall looking around at my spoiled, well-fed, attractively dressed classmates in wonder: what don’t you understand, I asked? The reasons behind their behavior are obvious. We’d have done exactly the same, in their shoes.

If Juan felt anything abnormal as he added me to his herd that afternoon, he was hiding it well. He looked at my satchel curiously for a moment and then turned to whistle at the goats. I’d always been curious about how exactly shepherds directed the movements of their flocks. As far as I could tell, there wasn’t much to it. The goats either knew this particular circuit so well that they needed no guidance, or they were so well trained that they wouldn’t allow themselves to stray more than 70 or 80 feet from Juan. It was curious how they managed to stay constantly mobile while still managing to strip what greenery they could find off of branch and bush. The only time they seemed to increase their pace was when we neared Juan’s homestead.

Everything looked different up close. What had seemed haphazard from the ridge made slightly more sense at this level. A pack of seven or eight dogs greeted us as he opened a wooden gate and directed the herd towards an alveolate series of pens. Everything was handmade here. Absolutely nothing looked like it had been purchased at a Home Depot or a Lowe’s. It struck me that Juan probably hadn’t ever seen such a place – perhaps he couldn’t even dream of a building that large. Trailing sadness came respect. Somehow this man had survived – no, flourished – in a cold world ruled by colder narco-minds. I couldn’t help but pity him, yet it was probably also true that I had more to learn from Juan than he did from me.

After leading his flock into a final enclosure, Juan checked some wooden containers to see if there was sufficient feed. A few dozen goats in nearby stalls stuck their heads out to watch us. After finishing his tasks, Juan led me deeper into one of the barns. He showed me one of his sheep that had been somehow wounded on one of its back legs. It hobbled over to Juan and nuzzled its head into his thigh.

“What attacked this?” I asked.

“Un perro.”

“Not one of yours, I’m assuming.”

“No, one of the wild ones. It was very lucky that it happened right in front of me.”

“You managed to chase it off?” I asked, running my hand over the neck of the sheep.

He turned to smile at me. “No. I killed it.”

“No mercy for dogs,” I smiled back, repeating the expression I had learned from the Hammer’s goons.

“Asi es, gavacho. Still, she almost died from the freezing.”

I didn’t understand what he meant by this, and it took him a moment to understand that wherever I came from, it was a place without sheep.

“When a wolf or dog attacks a sheep, usually they only have to wound it to make it…quit.”

I searched my memory for the Spanish term for “shock” but couldn’t come up with it. “It just stops moving?”

“Si, it just gives up.”

“People are like that too, sometimes.”

“Si,” he added sadly, before giving the sheep a last pat and turning to leave.

The main house in the compound was a collection of add-ons. What I took to be the original structure was constructed of cinderblock. Like many of the homes in rural Mexico, you could see the terminal ends of rebar sticking up from the roof like dozens of antennas. Several ipsilateral extensions made of what was either dilapidated adobe or recent wattle and daub stretched out from this, one ending in a large storage container, like you see on cargo vessels. It was dented and a bit rusted, and I couldn’t help but remark that there must be one hell of a story on how that came to rest way out here in the middle of Nowheresville, Mexico. Juan smiled at me again in response. A long transverse covered wooden porch completed the estate, and opened onto the front door. On the left side of this stood a wooden series of shelves mostly covered by a blue tarp. Several wires crawled out of the top of this and ran up onto the roof. Juan noticed my gaze and pulled back the edge of the covering.

Inside sat roughly a dozen car batteries, wired in parallel. I stepped back from the porch and walked around the side of the house until I could see the edges of at least two small solar panels. Panels, I noted, that looked exactly like the ones I had seen on the country homes of the narcos in and around Cerralvo. I met Juan back on the porch. He gave me a small, proud smile as I pointed at his set-up.

“You dog,” I laughed.

“Como?”

“I bet there’s some rich pendejo down the road somewhere that can’t figure out why he’s always a few watts short.”

The stare he gave me was pure confusion, and I reviewed the words I had used in Spanish, searching for the error. Juan finally just shook his head, looking slightly injured. It came to me as he was turning to open the door: he didn’t steal the panels. More likely, they were a gift from whatever narco-lord owned the land. I tried to imagine how an honest man would feel if such a criminal came bearing gifts. What could you say? You have children, a wife, and no power. They have AK-47s and grenade launchers and a tainted present you’d better take and act damned happy about, lest you end up fertilizing the dirt beneath your feet. And Juan probably thought I was one of them. This wasn’t dinner between friends. It was a serf begging his lord to think well of him. I cursed under my breath as I crossed the threshold.

Whatever political maneuvering Juan was attempting to juggle with me, his wife wasn’t having any of it. I never knew her name. When Juan introduced me to her, I had just been led into their kitchen, and he simply referred to her as “mi mujer.” Whatever her name was, she was an alchemist of sneers. She graced me with one that seemed to say, “So this is the bastard that’s caused all of this ruckus.” It only deepened when I bowed slightly to her. She harrumphed and turned back to the same sort of fireplace/oven combo that I had back at the cabin. I was instantly reminded of the Hammer’s wife, Esperanza, and figured that the two of them would probably get along well. If I couldn’t come up with anything else, I figured I could get both husbands a copy of Uxoricide for Dummies for Christmas the following year. If Juan noticed her complete deficit of manners he said nothing. Probably knew better. A group of three girls peered in at me from behind a curtain that led to what looked to be a bedroom, and Juan introduced them. The eldest was probably 14 or 15, the youngest 8 or 9. This last had immense eyes like a child in a Keane painting, and with these she scanned me sagaciously. Juan was obviously very proud of them. They were excused and then I understood that they would not be eating with us. Juan led me to the table and I sat, looking around in an attempt to cover up my unease.

The true level of this family’s disconnection from the modern world came into focus as I collected the details. You can usually glean a wealth of easy data from the constellation of small knick-knacks that a family chooses to display in common areas, but there just wasn’t anything here in the way of unnecessary material. There were no photographs on the walls, no books on any shelves. The only apparent deviation from the drab design scheme was a six-year-old wall calendar from a tortilleria that featured a drawing of la Virgin de Guadalupe. A small homemade whatnot stood in one corner, but the only item gracing its surface was Juan’s thermos. The light fixture hanging above the table consisted of three naked bulbs that drooped down, looking like ripe fruits made of light. I glanced over at Juan’s wife, my eyes roving over her cookware. Everything appeared as if it had been welded in someone’s backyard. She was wearing a long, nutmeg-colored woolen dress that could have been homemade, though not knowing much about the art of knitting I wasn’t certain. My god, I thought: how did the girls attend school? Were they destined to live and die in these ravines? Had Juan done the same? No wonder the unnamed virago hated my guts: this was a rough life, and whoever I was, I represented the sort imbalance that could doom them all. What would I have been like if I had grown up in this place? Would I have been aware of the names of the planets? The existence of Shakespeare or of a place called Japan? It struck me that perhaps Juan didn’t speak much because he didn’t have much to speak about. That was probably an unfair thought, but I still wonder about the richness of his mental life, all these years later. The memory of him always gets under my skin and pulses, like a splinter. I can’t help but also wonder if there are people out there so full of ideas and knowledge that they are to me now as I was to Juan then.

The wife was not to dine with us either, apparently. I don’t actually know what to call the soup she prepared for us. It was sort of like menudo, only with goat meat. She served it with blue tortillas. My eyebrow must have risen when I saw these because the wife snorted at me, her whole demeanor seeming to broadcast that she’d personally seen Jesus die.

The tortillas nagged at me. I had known of the existence of such things, but I’d never seen them before in either Cerralvo or Monterrey. I waited until we finished our repast and were stirring our coffee before I broached the subject.

“Juan, where are we?”

He gave me one of his innocent smiles. “Why, in my kitchen, Conrad.”

If it had been anyone else, I’d have thought he was being a wiseass. I shook my head. “No, no. I mean, where are we, like on a map? You know maps?”

“Ah,” he nodded. “Esperate aqui.” He stood and pulled to one side the curtain that separated the kitchen from one of the attached rooms. I heard him open what sounded like a heavy chest. He returned with a small collection of worn papers. I had hoped for roadmaps, but instead what I got looked like graded elevation charts, like something used by civil engineers to build train tracks or roads. The first appeared to be too hyperlocal for my purposes. It did show a series of what looked like county roads that I tried to trace, one of which ran into a larger thoroughfare near the top left corner that was labeled “45” in pen. Close to one of these smaller roads was a red circle. I looked a question at Juan. “That’s Villa Bermejillo. It’s where I take the animals to be sold.” I turned to the next map, but it was also far too local to help me. The next was broader, and included a portion of the border with the United States.

“Where are we one this one?” I asked. He leaned over and shrugged. I took the first out and laid it next to the third. Highway 45 made a slight but oddly shaped dip to the west at one point not terribly distant from our portion of the mountains, and I tried to locate it on the larger map. I finally found it about 25 kilometers south of Hidalgo del Parral, near Villa Ocampo. Fuck me, I thought. I’m in Chihuahua.

“Estamos en el estado Chihuahua, Juan? O Durango?” He just shrugged again, clearly letting me know we could be in Singapore for all he cared. I took my satchel off the back of my chair, where I had hung it when I was showed to the table. From it I removed my notebook and some pens. Juan seemed very interested in these pens, so I handed several to him as gifts. His eyes lit up and he bowed his head graciously. I spent about 20 minutes making a map that I thought might help me if I had to hike my way back to Cerralvo. Nuevo Leon wasn‘t even on this map, but I knew that Gomez Palacio on the eastern edge of the page wasn’t too far from Torreon – which was almost exactly due west from Monterrey. I estimated that I was close to 500 kilometers from Cerralvo, or thereabouts. A long distance to ride one’s thumb, but all I really had to do was get to a larger town that had a bus depot. I thought about asking Juan if Hidalgo del Parral had such a building, but then thought better of it. The man didn’t know what state he lived in. I might as well ask him if there was liquid water on Wolf 1061c.

I looked up to find Juan still smiling at me. What he must be thinking of me, I couldn’t imagine. As much as I wanted to, I couldn’t envy his simplicity. I don’t know if he’d have chosen it, given the option to know more about the world. The weight of all of the billions of problems I couldn’t solve pressed on me, and I reached into my satchel again. Juan’s smile broadened as I removed my iPod. I reached in again and pulled out the charging plug.

“I don’t know if you have the outlet for this; if not, I’m sure you can figure out how to make one.” I handed the device over to him. “You remember how to scroll through the menu to find the stuff you like? I already changed the language to espanol.” He simply stared at me. I don’t think he understood what I was saying. “It’s a gift, Juan. Un regalo.” He looked down at it and then up at me again. His smile faltered. Something battled behind his downward eyes tor a time. Finally, he looked up at me and smiled again. The lights hanging above us glittered off of something desperate and disappointed in those orbs, something no smile could ever conceal. “I’m sorry it’s not more, Juan. What were you hoping for? Equipment of some sort? A truck?”

He waved my comments off and set the iPod down on the table, picking up his cup of coffee with his other hand. “No, no, I say we are doing well. The patron has already been very kind.”

Bingo, I thought. ‘Whatever you were hoping for,” I said, standing. “You should ask for, the next time you see him. I’m no one, do you understand?”

“Un soldado?” he asked, innocently.

“Something like that, sure.” I think he wanted to believe me, or, perhaps more accurately, his desperate circumstances spawned a hope that badly needed him to believe me. I thanked him again for dinner and left. The walk back to the cabin was blessedly cold. I felt the light breeze run across and through me, and it felt as if it were carrying pieces of me away. By the time I had made it back to my abode, I had made a few resolutions vis-a-vis my owners, decisions I didn’t think they would like very much.

My last few weeks at the cabin were some of the calmest of my life. I wasn’t completely at peace; I still stood aghast at the past works of my hands, still unable to piece together how I had descended so deeply into madness back in Texas. But in terms of my immediate problems, I felt completely unburdened

My health had noticeably improved. By mid-February all of the bruises on my chest and abdomen had faded away, and from what I could tell from my reflection in the cataracted glass, so had the wounds on my face. My hikes increased in length, and I began jogging for long portions of the trail. I’m not going to say I felt good, exactly, but I felt strong and as clear-headed as I had in many years. I felt like a page had been turned.

Juan didn’t come around anymore. This saddened me, but what could I do? I wasn’t in any position to help him beyond the occasional nip of mezcal. I thought about leaving the remaining bottles out in the open along paths I knew he used, but that seemed kind of pathetic. If he wanted a drink, he would have to stop by and say hello.

The morning my peace and heartfelt resolutions ended was pretty much like the 60-something days that had come before. I was roughly a mile from the cabin when I first heard the sound. I wasn’t exactly sure what it was that I had detected, but after thousands of hours haunting these trails, I knew it was something out of place. I paused, waiting. Just when I had started thinking that my ears were playing tricks on me, I heard it again, closer: the sound of tires rolling over small rocks. I thought rapidly. There were only a few dirt roads that wound their way through these woods, and one of them was a few hundred meters to my left. That one I had followed for miles on numerous occasions, as it was the one that Abelardo had used when he deposited me here back in December. That connection had me sprinting back towards the cabin. I arrived at a small overlook in time to see a metallic gray SUV pause at the cutoff to the escondrijo. The driver was obviously trying to decide which direction to take. After a few moments, whoever they were continued going straight. I almost ran down the ravine in an attempt to get their attention, but a small internal voice demanded that I pause and think for a moment. The SUV continued to creep down the road, and I wondered if I was watching my ride out of here vanish for good.

But why was it creeping? And why wouldn’t Gelo send Abelardo, who knew exactly how to find me? If it wasn’t Gelo’s people, who might they have sent? It surely wasn’t the Hammer’s people, I realized suddenly. The SUV was a Land Rover, not the big one, but still very expensive and very ostentatious. The Hammer didn’t do flashy, he abhorred attracting attention the way the small mice in the cabin did. Someone else, then. Maybe not friendly. In any case, they would come back, whoever they were, because that road ended after several kilometers at an abandoned homestead. It was happening too fast, I thought, as I watched the vehicle disappear in the distance. Bottom line, I reasoned, was that they would be back, and I couldn’t just sit here. I started running down the path towards the cabin.

It wasn’t so much a planned act, but I instantly went for the pistol as soon as I barged through the door. In case this was my way out, I had to be here, but I didn’t have to be here unarmed. I exited the cabin, closed the door, then ran back inside and lit a fire. I wanted whoever that was to think I was inside, unaware of their approach. I exited again and hid myself in a copse of pines. Anyone approaching the front door would have to put his back to me. All of that free time, and I’d never once contemplated a hostile approach. I raged at myself for having been so dense, then forced myself to take slow, deep breaths. Whatever this was, it would be easier to deal with if I wasn’t flirting with Condition Black.

Within fifteen minutes I was hearing the tires again. I flattened myself against a thick trunk and watched as the vehicle pulled up and stopped, roughly 60 feet from the shack. The driver simply sat there for a moment, then turned the engine off. I held my breath as the door opened and someone stepped out. It caught again when I saw who had come for me.

When I had last seen Chespy, he was driving a 3-series BMW, wearing a suit, and bringing me my first very-clearly-not-fake Mexican ID card. Aside from a pair of rock star blue ostrich boots, he had looked about what you would get if you’d shot a Brunello Cucinelli advert in the middle of a war zone. He’d lost the suit, replacing it with some designer selvage jeans and an artfully worn reddish-brown leather jacket. He paused to survey the cabin before opening the fly of his pants and releasing a steaming jet of urine. If this was his version of a sneak attack, I remember thinking, it needed work. He stomped his foot a few times and then buttoned up his jeans. I gripped the handle of the pistol as he approached the door. If he was going to produce a weapon, it would have to be soon.

He was nearly at the entrance when he did a very curious thing. His hand was raised to knock on the door when he froze, his eyes aimed downwards towards what looked from a distance to be the point where the cabin’s foundation met the earth. My skin started to crawl as he angled it down and then to the right. I had just enough time to think, “Shit, he’s looking at my footprints” before he swiveled around to stare back in my direction, finding me almost instantly. His teeth shoaled in the midst of his broad face and he waved comically. There didn’t seem to be any point in hiding, so I left the copse slowly, walking with the pistol hanging at my side.

“Mother fucking Grizzly Adams,” he quipped, his left hand stroking his own facial hair. His right, I noted, continued to hang loosely at his side. “Talk about going native. You planning on shooting me, guedo?”

“I haven’t decided yet.”

He laughed. That’s one thing I learned from Chespy that is still incredibly useful to me today on occasion: there’s nothing that unnerves a human predator more than someone who genuinely finds their display of arbitrary power humorous. He was still chuckling when he raised a finger. “One, if Don Rogelio had wanted to kill you, he’d have just shot you in the face in Cerralvo. It’s not like they haven’t done it before. Two,” he continued, lifting another finger. “If he had wanted to erase you, no way they would have called me to do it. I’m way too fucking expensive, and the politics, wooo!” He rolled his eyes at this, waving his hand in a “forget about it” gesture. “Three, if they had wanted you dead and were concerned about you being a threat, they‘d have sent a five man team that assaulted this place at 3am with tactical shit that your SWAT cops can only dream about.” He paused for a moment, letting the smile dissolve from his face. “Four: I’m telling you this straight, this ain’t hubris. I wanted to shoot you, I could have my juguete out and a bullet in your head before you made up your mind to do anything about it.”

I thought about what he’d said, and realized all of it was probably true. “Awfully sure of yourself, tio.”

He shrugged. “The confidence that comes from not giving a damn. Can we get the fuck out of here? I’m freezing my balls off.”

I placed the pistol behind my back and into my waistband. “I’ll need a few minutes to pack. Nobody called to tell me my residence here was at an end.”

“By your leave, sir,” he bowed and waved a hand towards the door. It didn’t take long tor me to load what was mine into my pack. I wrote a note to the Chivero that he could have anything and everything inside the cabin, and then wrapped this in two plastic sacks. I grabbed one of the bottles of mezcal and took the note to the stump of the tree where I had first met Juan. He would find it or he wouldn’t. Chespy gave me a curious look but I ignored him. I didn’t feel I owed him an explanation. I started straightening the place but Chespy impatiently grabbed my pack with one hand and my arm by the other. He mumbled something about “campesinos” as he marched me outside. I took the pack from him and loaded it in the back of the Rover.

Stepping into the vehicle, I removed the pistol from my waist and slid it between the door and the seat as I settled into the glove-soft charcoal leather seats. Chespy gave the cabin one last glance and climbed in next to me.

“You have nice taste in cars,” I admitted to him.

“Oh? Can’t take credit for this one. The next time I see Pablo I’ll tell him you approved. Course, that would require me to dig him up first.”

I didn’t say anything because…well, what the hell does one say to that?

He smacked my shoulder and guffawed loudly. “My God, you are no fucking fun. The car’s mine, relax. You can have it in a few months when I get tired of it.”

“Uh, thanks. I think.”

“You haven’t seen the best part. Atende. One,” he said, pointing down at his seat. “Pressure sensor built into the seat. Two, all the doors are closed. Three, rear defroster,” he said, placing the key in the ignition and then flipping the switch for the defroster. “Four, XM station 81.” He leaned forward and engaged the radio, turning the dial until it synced up with that particular station. He then reached into his jacket and removed his wallet. Taking out what appeared to be a regular credit card, he continued. “Five, both front windows, while six…” he paused, lifting the toggles for the passenger and driver’s windows while simultaneously waving the card over the portion of the console just above the radio. I heard a click and an entire section of the dashboard lifted up slightly. Chespy leaned forward and lifted this up. Inside was a contraband well of perhaps 8 by 18 by 10 inches. I was impressed.

I’d seen a few traps during my time in Mexico, but never one that obviously utilized relays. It seemed a little overkill to require six input circuits to be completed, but what did I know? The first two – the seats and the doors- were obviously designed to foil a highway inspection, because those would almost always be conducted with the doors open and without anyone sitting in the driver’s seat. I was willing to bet that the radio station was an emergency trigger: if Chespy had been forced to open the compartment, setting it on, say, station 91 might have allowed the sequence to move forward while at the same time sending an emergency phone call with GPS coordinates attached. I was still contemplating this when I noticed that Chespy was staring at me. I met his gaze finally, shrugging.

“Mine has 9 relays. Six is kind of amateurish.”

His grin erupted again. “Cabron, I’ve seen your bicycle. It doesn’t even have 9 gears.”

I couldn’t help but smile back at him. “Witty banter isn’t a whole lot of fun when your opponent is practically omniscient.”

His smile downshifted slightly, and his eyes turned thoughtful. Finally he nodded slightly. “There it is.”

“There what is?” I asked suspiciously.

In response he merely turned the key in the ignition. “Time to go. Put that shooter away, unless you want to explain to half a dozen military checkpoints why you happen to be immune from about 50 laws.”

I placed the pistol in the trap and watched how Chespy locked it back in place. I turned to watch the cabin disappear as we stalked our way down dirt roads for twenty minutes before arriving at a two-lane asphalt road. Unlike on the trip out, where I was still coming down from a week’s worth of oxycontin, I paid attention to the route. It actually wasn’t quite as remote as I had envisioned, and within half an hour or so we began to see occasional cinderblock homes along the roadway.

It’s hard to sit next to someone like Chespy and not ask questions, but I sensed that whatever answers he gave me would come attached to a fairly hefty price tag. Who chooses to live like this? I badly wanted to know. Maybe the answer was as simple as a wave towards the index of poverty that clenched itself all around us, hardscrabble lives devoid of voice or autonomy. I didn’t think that would be his story, though. I never did find out exactly who he worked for, or what his actual job title was. Later on the way back to Cerralvo, he mentioned he picked me up only because he was on the way back to Monterrey from Los Mochis, and the cabin wasn‘t too much of a detour. When I looked this up a few weeks later, I found out that Los Mochis was deep in the heart of Sinaloa Cartel territory. If the Hammer was head of an independent trafficking group that paid taxes to the Gulf Cartel, and if Chespy was somehow connected to whoever Gelo’s bosses were, that put him squarely in the GC/Zeta camp, the most vicious enemies of Sinaloa. Was he an emissary, then? He seemed a poor diplomat, unless the only rules of decorum one cared about were those of the tiger. I suppose el Chapo’s people must have respected his brutality, and maybe even liked his quick and ready laugh. Still, I wish I had spoken to him more when I had the chance. One does not generally come into contact with genuine cartel assassins very often.

We reached the first military checkpoint within 90 minutes. The layout of this was more complex than the one outside of Cerralvo. A soldier with an automatic weapon waved us towards the right, where a corporal waited with a clipboard and radio. This latter had almost reached the Rover when another man called out to him. The corporal looked annoyed but he apparently obeyed because he slunk away. The soldier that replaced him was a sergeant. Chespy apparently knew him, because their conversation was both amicable and familiar. Nothing much was said, just mere pleasantries, but embedded within the phatic nonsense must have been something of value because the two certainly laughed more than was reasonable. Two minutes later we were back on the road.

“What?” Chespy asked, after glancing my way.

I didn’t know quite how to put it, so I just blurted it out. “It’s too easy. These checkpoints are completely pointless.”

“Yeah, sure, if the actual purpose was to stop people like us. But that’s not what they are about. The people need spectacle. They need their symbols of state power. And you Americans need to see this shit, so that all that Merida Initiative money can get trucked down here, all nicely wrapped up so we can steal it.”

I turned slightly so I could better watch his face. “I get the power of propaganda. I understand how governments need to…I don’t know, justify their political power with reasons. But it’s not real power, and it’s very obviously not real power. I saw that the first time I passed through one of those. Nobody could be fooled by any of this.”

“You honestly think we give a fuck if they are fooled? Their function is to obey. They can think whatever they want, so long as they do what they are told,” He paused. “Seriously, the fuck’s up with all of this fake incomprehension? You know you understand it. I don’t need to explain what hegemony is all about to you, of all people. Gelo may not know why you are down here, but we’ve known from almost the first day. I knew the first time we met.”

He must have seen a micro-expression of alarm ghost across my face because he smiled. “Sugar Land?” These two words arrived like cluster munitions and I sunk back into the seat. “You think we care? We don’t. We’re like Jesus. We forgive sinners. So long as they are vicious and our sinners.”

“You have a heart of gold.”

“Yep. I keep the fucker in a box under my bed. Actually, it also belonged to Pablo.”

I laughed. The gods help me, but I actually laughed.

We drove several hours on Highway 40D, and the Rover parted the various veils of security like a thermal lance. Evening approached us as we entered Monterrey. I was familiar enough with the layout to follow our progress on a mental map of the city, so when Chespy finally pulled up to an ultramodern glass condominium building, I knew I was only a few blocks away from the Macroplaza. Chespy put the SUV in park and turned in my direction. I followed his gaze to the building, the surface of which was bending the reflected image of the surrounding neighborhood in funhouse ways.

“4F,” he said finally, handing over a magnetic key card.

I contemplated these words while I looked out the window. “What’s in 4F?”

“Your future for the next few weeks. Maybe longer. Tal vez el sendero obscuro, si lo puedes alcanzar.” He placed the card down on the central console.

“The shaded way?” I translated out loud.

He shrugged. “Things need names. That one’s en vogue. It will be called something else if the inmates ever manage to take over the asylum.”

“Maybe I prefer to stay in the sun? You know, vitamin D, chicks in bikinis. Sunny stuff like that.”

His laugh was like the immense vacuum of space. “It‘s cute that you think have options. I told you when we first met that we can do anything. You shouldn’t forget that.”

“Hard to forget a thing like that,” I said, continuing to sit there, not wanting to look at him. “The shaded way. That has a sort of ancient, mystery cult ring to it. Kind of religious, no? Like something out of Milton, maybe.”

“There it is again,” he said softly, and if I didn’t know better, his tone was approving. “Never read him, though the Padres certainly tried to force that shit down my throat often enough.”

That made me turn back towards him. I scanned the lines of his face, trying to guess his age. “Let me guess: one of Loyola’s boys?”

He grinned. “‘Give me the child until he’s twelve, I’ll give you the man.’ What mierda. Didn’t work so well on me, did it?”

“I don’t know. The Jesuits had their share of psychopaths. You probably fit in better than you think. Or maybe you should have paid more attention to them when they tried to shove all of that in you. Milton and Dante seem surprisingly appropriate for this place sometimes.” I paused, thinking. Almost without meaning to, I began to recite words I hadn’t thought about in years.

“‘I toiled out my uncouth passage, forced to ride the untractable abyss, plunged in the womb of unoriginal night and chaos wild.‘”

“You don’t say,” he did say. “I guess I’m the ‘untractable abyss.’ Kind of like the sound of that. Kid?”

I looked at him. “Yeah.”

“You think I don’t know what a pivot or stalling tactic looks like? Now get out of the fucking car before I toss you out.”

I got out of the fucking car. Fast.

No sooner had I grabbed my pack out of the backseat and closed the door he was off, tires squelching their goodbye. I stood there for a few minutes, trying to decide which of my options was the least awful. Finally I turned and moved to the entrance of the building. I could see a nicely appointed foyer through the glass, everything very crisp and full of right angles. The reader on the door accepted the card, and a little green light blinked its approval. I tried not to look at my reflection in the glass as I placed my palm on the stainless steel handle and pushed open the door. Tried not to pretend those first few steps didn’t feel like a descent.

To be continued…

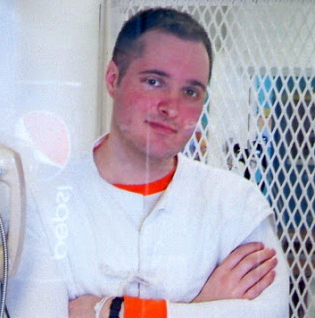

Thomas Whitaker 999522

* for more information click here

Donate to Thomas’s education fund

This is Thomas’s Amazon.com wish list

10 Comments

Anne

February 10, 2019 at 8:21 pmJoe, your comment is an insightful and important one. I started reading Thomas's blog believing I would be learning about the inner workings of a "sociopath," as the courts claimed he was. But after reading several entries, I had my suspicions about the law's so-called expert ruling. And after reading all 152, I knew they were wrong.

The first clue? These entries span Ten. Whole Years. Actual sociopaths, psychiatrists and psychologists have discovered, will quickly abandon a course of action if it's not working for them. If anyone goes back and reads the vitriol Thomas received during his first year of posting alone, they'll realize it was obvious early on that this site wouldn't exonerate him – in fact, its presence often made things worse for him in prison because guards targeted him much more frequently. If he were actually a sociopath, then, he would have abandoned it long ago. At the very least, he would have written entries proclaiming what he knew would get him positive attention – that he was a completely unquestioning Christian, that he was shouldering his sentence like a saint, and so on.

Instead, for a whole decade Thomas has written 152 entries where he struggles with and asks difficult questions about faith, castigates himself again and again for his past, struggles to advocate for other less-educated prisoners, and describes in detail the mistakes he makes while trying to find some sort of redemption on Death Row. A sociopath he most certainly is NOT.

And if people need evidence beyond mb6-based textual and historical analysis, they can read the appeals documents, which are open to the public online. Specifically, they should consult Whitaker v. Thaler (1st Amended Petition) – Exhibits F, G, H, K, L, M, and M.1.

And what do these contain? Extensive diagnoses and commentaries from FOUR separate doctors (spanning from before Thomas' crime, back when he was 17, to several years ago). Every single doctor REJECTS the notion that Thomas is a sociopath – most even include affidavits where they specifically refute the lawyers' amateur and erroneous attempts at medical diagnosis. Thomas suffered from a severe Delusional Disorder; and at the time of his crime, his Global Assessment of Functioning was a 25, which means he was in the grip of overwhelming delusions. Most doctors would actually recommend hospitalizing someone with such a low score (out of 100, with 100 being accurate functioning).

But I fear, Joe, that you and I are in the minority. Most people will just accept the sound-byte, Twitter-simple world we live in and not bother to actually READ about the facts or QUESTION the law. As citizens, though, that's what we're called to do. In fact, as moral humans, that's what we're called to do.

But unless people start bothering to take the time to critically think about the case for themselves, a man is going to die. A man who is NOT a sociopath or evil incarnate, as the courts have brainwashed the public into thinking – but a man struggling to be moral and find redemption. A man who, all along, needed medical help.

Anonymous

December 19, 2018 at 2:30 pmThis comment has been removed by a blog administrator.

Anonymous

December 19, 2018 at 2:30 pmThis comment has been removed by a blog administrator.

Joe

November 8, 2017 at 2:26 amI was devastated to hear today that Thomas has been given an execution date (February 22 of next year).

I can only hope against hope that are granted clemency.

I hope you can find some solace in the fact that I've witnessed several hard headed pro-death penalty conservatives change their minds about the death penalty and actually become opposed to it after persuading them to read your writings.

There are lots of people out here who love you and are thinking about you.

Anonymous

October 16, 2017 at 11:16 amYou probably don’t remember me, we went to elementary school together, The Highlands, lol!! So, my question is, after watching and reading about you..,if you weren’t what you thought your parents believed you were, searching for this other man you are…who was it you didn’t show them??? For me, you didn’t want to fit into the preppy Sugar Land ideal. So, with your eloquent writing and devious almost secured plan…what was or is it they didn’t get?? Who are you then?? Evil or something hidden behind the evil? Or just a broken man?? Never could calm out his want for himself?? I’m very curious. So much for us to correspond!

A Friend

July 31, 2017 at 12:47 amThomas received some books recently that did not contain a receipt. To whomever sent them, he sends his sincere appreciation!

Anonymous

July 17, 2017 at 6:02 pmI always look forward to a new entry from Thomas. I was also distressed to hear about your appeal. Don't give up.

Anonymous

July 13, 2017 at 10:12 pmAnother fascinating chapter. Looking forward to the next one Thomas. Sorry your appeal was turned down. Where there is life, there's hope. Even if it's a slim one.

Here is the link to the judgement: http://www.ca5.uscourts.gov/opinions/pub/16/16-70013-CV0.pdf

Anonymous

July 13, 2017 at 7:43 pmAnother awesome chapter Thomas! I am really enjoying this series. Obviously I'm aware of your case status as we frequently write, but I'm still optimistic and hopeful. Keep your head up and let your writing being your vessel for expression. You've got a natural talent for it. Be well, Ken

Anonymous

July 10, 2017 at 2:38 amAlways great to hear from Thomas and particularly to get another installment of "No Mercy For Dogs".

This tale is so gripping; it's always great to see a new chapter and they always leave me eagerly anticipating the next installment.

I was deeply saddened to learn that Thomas' 5th circuit appeal was turned down in April.

I wish I had some pithy words of wisdom and consolation to offer on that front. My imagination fails me.

All I can say is that what you, Thomas, write here, matters. A lot, and is not falling on deaf ears.

Keep your chin up bro. I don't know what else to say.