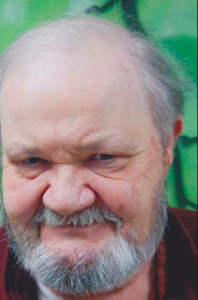

By Burl N. Corbett

Every evening, my father played his violin by the upright piano in our dining room. The nightly concerts were among my first memories, but I can no longer recall if I listened from my upstairs crib, or downstairs in the old wickerwork bassinet my mother wheeled from kitchen to living room in our tiny stone farmhouse. These memories have no faces, just a soundtrack, and I had no name for that, either. I knew neither thread or needle, but it occurs to me now that he was stitching my world together note by note, his swooping bow composing my future memories in an elegant cursive, tying up my earliest impressions with elaborate ribbons of bowed glissandos and pizzicato triplets. My mother would later recall that I was a happy baby, giggling and gurgling and pumping my little arms and legs as if I were conducting Father’s performances.

Mother also recalled how I had cried and cried the day that Father traded in his worn-out ’38 Chevy for a new ’51 sedan. I had loved the older car and the cozy backseat beds Mother fixed for the long twenty-eight mile trip home after visiting her distant family every other Sunday night. In my memory, it is always winter, it seems, and I can still recall the comforting weight of the wool army blanket into which I was tucked. Enshrouded in a cocoon of warmth, I watched the blazing orbs of passing headlights wheel across the inky firmament of the headliner, lying half-asleep, counting the glowing streetlight comets zooming past the windows until the tires’ soothing purr lulled me to sleep. The next morning, I would wake in my sunny bedroom, magically transported from the ancient world of night to a freshly born universe drenched with light and the reassuring murmur of my mother softly singing to life our breakfast world.

The old car was soon forgotten, and I slept just as soundly in the new one. It had a radio, and although I drifted off amid the same lights, I did so to the sound of my father’s voice singing along with the popular songs from his adolescence, the pre-war soundtrack of his life. His strong baritone reassured me that the world was balanced just right, and that I was loved and protected as I rested groggily at its delicate center, listening to the monotonous drone of the tires only a few feet from my prone body. In those days of ineffectual heaters, sometimes a faint scrim of frost obscured the rear windows, but secure in my warm nest I imagined that Father’s singing coupled with the bravely struggling heater had repelled the cold. But all things must end, and one evening I abruptly announced that I was too big to be tucked in like a baby, and that part of my life was over.

But, some memories are as persistent as an unwisely fed stray cat, and as a friend and I drove across the country a decade later, I rested in the backseat of another old Chevy, watching a similar light show of pinwheeling headlights upon a torn headliner and thought of my father back home, dreaming perhaps of a younger me. And I thought too of my old crib and bassinet, both covered with dust, their rips reinforced with spider webs, sitting empty in the sad attic where all of our keepsakes and memories eventually go to den.

When I was four, my one-room schoolteacher paternal grandmother taught me how to read and write. An enthusiastic student, by the time I entered grade school I had become an ardent reader, devouring books well above my grade level. When I was six, my father taught me how to play and notate chess. At the time, the algebraic method of transcription was not widely used, and I laboriously registered each move, writing KKN-B3 and KBP-4, rather than the pithier Nf3 and g4. By the end of a long game, the letters and numerals sprawled down the page like arcane hieroglyphics decipherable to only us, the elite wizards of the chessboard. For no particular reason, Father saved each score sheet in the dining room china closet, and as the years went by, the pile threatened to obscure the dishes, until for no particular reason I declined to keep score. Soon, because of either my incipient adolescence or teenage indifference, I forget which, our competition ended, too. One day, I noticed that the heap of yellowing scoresheets was gone, but attributed its disappearance to one of my mother’s occasional cleaning frenzies. We still played now and then during the ensuing decades, but neither of us bothered to keep score; our eyes were upon the future, not the past.

My father had been a medic during World War II, a corporal in General Patton’s Third Army. Like many former soldiers, he rarely spoke of the war itself, only of the mud of France, the ruined buildings of Germany, the beauty of the Bavarian Alps. When his battalion visited Hitler’s mountain redoubt, the Berchtesgaden, he retrieved for a souvenir a small triangular stone from its ruined fireplace. As I later discovered, he had been at another of Hitler’s creations, a hellhole at which the iron heel of a lunatic doctrine had ground into bloody submission an entire race of people; a Godforsaken inferno of mass murder and torture, a place utterly devoid of hope, in which conscientious scorekeepers toted up the deadly tally with mad Teutonic precision.

But then, I knew little of these horrors; to me and my classmates – the boys, that is – the war was just an exciting adventure in which things got blown up. We drew fantastic battle scenes replete with tanks and battleships, airplanes and submarines, all engaged in unlikely tableaus of mayhem. With just a pencil and a few crayons, on sheets of lined notebook paper, we reimaged the war as an exercise in perspective, rather than the horrendous bloodbath that drenched four continents.

During the years of my military fixation, I assembled plastic models of warplanes and battleships, with a few jeeps and destroyers thrown in for variety, until my bedroom resembled the coast of England before the Normandy Invasion. Our home lacked a bathtub, but our small sideyard creek served quite nicely as the English Channel, a perfect spot to launch my glued-together armada. I suspended the airplanes from my bedroom ceiling, where they slowly spun in the breeze coming through the window screens, as if engaged in imaginary dogfights. But within a year or two, I put aside my substitute toys of mass destruction, my martial bellicosity tempered by smithies of a gentler persuasion, and returned to my books.

I was a curious child, a loner who explored our farm and the adjoining watershed forest until I knew every species of tree, every kind of flower, and every turn of the creek. I explored our house, too, from its dank basement to its airy attic. In the summer, I liked to sit in the sauna-hot attic until I became drenched with sweat. When I couldn’t bear it anymore, I retreated to the chilly basement, marveling at the floor by floor diminishment of the temperature – a drop from attic to cellar of easily sixty degrees. I also visited the attic in more temperate seasons; a trove of my father’s childhood books was there, as well as more recent paperbacks from the ‘40s and ‘50s. I loved to browse through them on rainy days, paging through the Mickey Spillane shoot-‘em-ups for the verboten “good parts” tacitly promised by the lurid cover illustrations of trashy gun molls sporting conical breasts that threatened to pierce their sweaters. On rainy days, it was easy to fantasize that the clay panpipes of the old mud dauber wasp nests along the rafters were emitting the rain’s one-note melody. Lying in the flat, even, dim light filtering through the grimy gable windows, I lay amid the forlorn discards of my ancestors’ pasts, happily daydreaming of an unguessable future.

During one of these visits, I discovered an album of love letters from my soldier father to my home front mother-to-be. Although his lovely handwriting was crabbed to fit on the onionskin paper, and a word or phrase had been blanked out by a hypersensitive censor toiling ingloriously amid the groaning gears of the vast wartime bureaucracy, his dislike of the war and his passionate desire to return home to the woman he loved was evident. Reading his letters was like reading his mind, and when he asked my mother if “she had ever been raped with her clothes on?,” I cringed with embarrassment, ashamed of my snooping.

The album wasn’t filled with just ancient billets-doux, however. There were black and white photos of my uniformed father and dressed-to-kill mother outside her sister’s house, juxtaposed beside scenic snapshots of undamaged French chateaus, German castles, and transcendent images of the Alps. To look at them, one would never guess of the horrors that had occurred in their shadows. As if to illustrate that very anomaly, there was also a series of photographs taken during the liberation of Dachau prison camp, where he had witnessed the ultimate human to human barbarity among countless day to day lesser ones. As I examined them, I felt with a shiver of revulsion as if the Angel of Death had lifted his dark robe to mock me, exposing himself in all of his hideous grandeur.

I had been raised on a sheep farm, and the death of a poisoned-by-nightshade ewe was fairly common. I had even watched with a queasy stomach the veterinarian digging through the ewe’s intestines, searching like a latter-day haruspex for a clue to its demise. And I had often held the heads of non-laying hens upon the chopping block while my uncle beheaded them with a hatchet. Death was no stranger, he just hadn’t yet stopped for a human client.

I had never attended a funeral, and on the rare times I had accompanied my parents to a cemetery, I wandered off while they were visiting their friends and relatives to read the epitaphs and examine the carven symbology on the older headstones. Even there, surrounded by its victims, Death seemed as remote as the hidden daytime stars: for why would I ever die?

But the people in the photographs, the corpses and the living skeletons whose burning eyes haunted one’s soul, had once thought the same, yet here they were, stacked in cords like Satan’s own firewood, or staring forever out of Hell itself. No amount of flowers or well-meant prayers would appease their tortured souls, and for their murderers there won’t be time enough in eternity to earn their redemption.

I never told my father that I had seen the photographs – I felt guilty, vaguely immoral, like I had when I looked at the salacious crime novel covers. It was difficult to reconcile the man who read Plato and Schopenhauer with the man who had also read such sleazy trash. Nor could I picture him recording those horrid events through a steady viewfinder, then returning to his tent to compose love letters to his wife. From that day on, I regarded my father in a new light, as an unknowable entity, a possessor of great secrets, a contradiction, even.

Although in his later years, my father would play his violin less and less, as if his artistic sensibilities had been retempered upon the anvil of a prosaic smithy to better withstand the vexations of a coarser era, I still liked to listen from the living room sofa as he valiantly stormed Dvorak’s “Humoresque,” stumbling at a difficult passage, cursing aloud, and then renewing his assault at the beginning. After getting a bar or two further in the trying composition, he would misfinger or misbow. “Son of a bitch!” he’d exclaim, then labor on, his curses replacing the libretto. Through much practice, though, he had managed to master a few slow pieces by his favorite violinist, Fritz Kreisler, lovely works that he played with eyes closed. Sometimes during an evening concert, I stood outside in the dewy summer grass, listening through the screened window amid the drifting pointillistic dots of lightning bugs, the hollow basso grunts of the bullfrogs in our creekside marsh accompanying my father’s ethereal serenade. Swooping bats basted the velvet heavens to the darkening hem of the earth, as they and the melody soared and plunged in ragged accord. The Milky Way spread above me from horizon to horizon, each star glittering in mute fury, and I craned my neck stiff watching it watching me. Eventually, the recital ended, and I went back inside, blinking in the light. Father never asked where I had been, and I in turn never asked where he went when he closed his eyes, suspecting that we had each been briefly transported into a private-but-somehow-mutual realm of ecstasy.

In every life there are moments so intense that they forever exist in some sort of quantum perpetuity, moments destined to endlessly recur in a Nietzschean wheel of eternal recurrence. If that is the case, then my father is diving to the ground this very moment, face down in the grass next to our backyard burn pit after mistaking the explosion of a carelessly discarded aerosol can for a mortar round. After standing up in obvious embarrassment, he explained to the picnic guests that his reaction was a survival reflex from the war, when he had carefully shepherded his fragile existence through a maelstrom of steel and fire. Although he tried to laugh the incident away with a sheepish smile, I could see that he had been wounded deep inside, and that the unexpected blast had probed that festering sore.

Later on, after he had downed several beers, I overheard him tell his brother how a horribly wounded soldier – his face and manhood shot away, blinded and legless – begged him for a lethal injection of morphine, pleading and bawling until my father quietly filled a syringe and placed it in the man’s hand. The next morning, the man was gone, a new patient in his stead. No questions were asked, no answers volunteered, and the war went on.

When Father noticed me listening, he changed the subject. Once again, I had caught an unsettling glimpse of my father’s secret history, leaving me with the unsettling suspicion that he had deliberately abetted a suicide. But, I reasoned, compared to the forests of corpses felled at Hitler’s death camps, his “crime” was inconsequential indeed, and I soon relegated its memory to the attic of my mind.

In 1963, the bland but cozy post-war society that my father’s generation considered their reward for saving civilization, was assaulted by a cultural revolution led by The Beatles. As though electing to rub salt in his “wounds,” I decided to learn the guitar, the better to emulate Bob Dylan, an artist whose music was a combination of my two favorite genres, folk and rock ‘n’ roll. Ever the good sport, my father not only bought me a nylon-string Martin, but paid for my weekly lessons, no small expenditure given his modest salary. Now it was my turn to sit at the piano cursing over mangled chords and sour notes. One evening, as I was fingering the tricky chords to The Beatles’ “Michelle,” my father began to play the melody on his violin.

“That’s a pretty song,” he commented. “Who wrote it?”

“The Beatles!” I proudly informed him, glad that he had finally acknowledged, accidently or not, an accomplishment of my generation’s favorite band.

“Hah!” he snorted derisively. “Someday you’ll find out that they paid someone to write their music.”

Nevertheless, he played the song to its end.

Now that I was a musician, too, we talked of our relative instruments. It turned out that his violin and another in the attic were spoils of war, taken from a bombed-out estate in Germany. Inside the piano bench was another, a leather-bound volume of classical favorites, entitled Sturm und Drang, mute evidence of the cultural refinement of the same nation that had perpetuated some of the worst crimes in the long and sordid history of the world. The troubling dichotomy didn’t escape me, nor deter me from trying to play the pieces. As I struggled through the copses of difficult keys choked with a plethora of sharps and flats, I mused over the paradox that if musical notation – like that of chess – is a universal language, then how could those fluent in both systems have committed crimes so utterly antithetical to the serenity and joy that they transcribe?

Finally, unable to resolve this enigma to my satisfaction, I put aside the irksome philosophical posers that had stumped finer minds than mine, and simply played the music.

As he aged, Father slowly retreated into himself. Never an outgoing man, he became a semi-recluse. Once he retired, he divided his waking hours between his downstairs reading chair before the unwatched television, his upstairs bedroom desk, where he typed letters to the pen pals he would never meet, and the front porch swing, where he thought his old man thoughts. He no longer played his violin; arthritis, not Dvorak, had finally defeated him. Turning to chess as a solace, he practiced against a chess computer until, on the rare occasions that we played, I struggled to prevail. But when senility established its first beachhead, he reluctantly gave up the game he loved, although for some reason, he kept a set-up chessboard in his bedroom. One day, it struck me that I was now older than he had been the evening that we had played “Michelle” together, and I felt a frisson of unease over my own mortality. Inside my being, there was still a recalcitrant child who resented being sent to eternity against his will.

My father may have thought differently, however, as he gradually sank into the quagmire of senility, wherein dwelt an ogre eager to steal not only his life, but his memories, too. It occurred to me that perhaps our memories are only on loan, are periodically recalled and redistributed, that maybe our lives are a series of recycled events endlessly reshuffled by karma. By that reckoning, perhaps someday in another world the Jews will slaughter the Germans, the chickens will hold the hatchets, and my head will rest upon the chopping block.

After much consideration, I rejected the premise. In such speculation lies madness: Lear raging on the heath, Nietzsche crying before a mistreated horse, Hitler ranting in his bunker.

As Father’s illness progressed his days sorted themselves into the “good” ones and the “bad.” Between these polar extremes lay the latitudes of “worse” and “better,” the longitudes of “normal” and “abnormal,” the degree of each a matter of debate.

A month before his death, I discovered him in his bedroom, eyes shut, big band music playing on his radio, his face without expression. For a second, I thought he had died, but then I noticed his right index finger keeping time on the arm of his rocker. Before he became aware of my presence, I quietly backed away, leaving him dancing with my mother under a glittering mirror ball in a pre-war ballroom, a begowned chanteuse crooning “Embraceable You.”

The last time I saw my father alive, he sat before the television he could no longer see, hands folded on his lap, his face a stony mask. When I asked if he was all right, he responded with a gruff “No!” I looked at my mother; she merely shrugged: What could she do? For that matter, what could I do or say that could ease his distress? Without a word, I simply left the room, leaving him to the fate that had been forged before either of us were born. He died in his sleep two days later.

My mother’s phone call awoke me at midnight; her voice frantic. “I can’t wake your father,” she cried, “come up here now!” Immediately I knew that Death’s carriage had kindly stopped at last. I raced up the hill in my truck, ran past my distraught mother into his bedroom, where he lay upon his back in bed, eyes open, his right hand dangling above the floor, a large bubble balanced upon his lips, glistening in the muted light of a bedside lamp. As I searched for a pulse I knew I wouldn’t find, I glimpsed my distorted reflection in the gossamer sphere. After closing his eyelids, I shattered my image with a fingernail, releasing my father’s last breath back into the world he had just quit. Now, his travails were over, his soul unburdened once more.

As I folded his cold arms across his chest, I thought, So, this is how it ends; this is my father in death. Now there’s nothing more to hurt you, Father, no more horrors to witness, no mirror to remind you of your lost youth. I pulled the sheet over his face and looked around the room, fixing forever the tableau of his passing.

Wracked with grief, I looked about the room, grasping for a peg on which to hang my sorrow. Then I noticed his chessboard on a small table, a game in progress. Next to it, lay a yellowed transcription of a game I had recorded nearly a half-century before. With a guilty sob, I turned to my father – my still, lifeless father – and wept for us both, regretting bitterly the inexplicable shadow that had fallen between our lives all those years before.

At his funeral, seven uniformed veterans fired three volleys from their rifles; the reports faded echoless in the vast, sun-washed cemetery. My father’s life would be condensed to a mere two dates – eighty-six years apart – embossed upon a simple bronze plaque imbedded in the earth; as a modest tribute to his traumatic service to his nation, every Memorial and Veteran’s day a tiny flag would flutter above his grave. As a bugler played taps, I thought of my father bowing his violin, eyes closed, transported to a temporary utopia wherein beauty trumped ugliness, and affronts to man and God such as Dachau did not exist. As a pastor who knew nothing about the deceased droned on and on, I scanned the sky for a fortuitous omen, perhaps a circling hawk or an auspicious crow, but there were only fleecy herds of grazing clouds, hazed before a gentle wind.

With solemn respect, the sergeant of the guard presented the coffin flag to my sobbing mother, then handed me twenty-one expended brass shells. Then my father, my poor dead father, was lowered into the ground, his duty over.

A few days later, as my mother was going through his things, she discovered a Bronze Star Medal, an honor that my father had never mentioned. What other secrets had he borne away?, I wondered. I recalled the hideously crippled casualty who had begged for release, and I knew beyond doubt that he hadn’t used the syringe that my father had “put in his hand,” nor had he died from his wounds. No, my father granted his petition, and administered the overdose. Perhaps for the rest of his life, my father saw the man’s ruined face every time he played his violin, the only good thing he had brought back from the war. Maybe his attempts to play the divine music of Bach and Shubert and Beethoven was his petition to them to intercede with God, to request Him to suture and heal the grievous lacerations upon humanity that had been inflicted by their countrymen.

Although I inherited Father’s violin, I never learned to play it. It rests on my bookshelf, next to an empty cartridge mounted on a walnut plaque. The brittle notations of our long ago games are in a trunk, waiting to be replayed with a future grandchild.

Sometimes on summer evenings, I sit at night on my father’s wooden porch swing, remembering my six-year-old self nestled on the backseat of the old ’51 Chevy, listening sleepily to his father singing along with Sarah Vaughan’s “Someone to Watch Over Me,” while outside the half-frosted windows a galaxy of passing headlights and glowing streetlights wheel past in mute splendor. Then I look across the road at the moonlit meadow alive with fireflies, and I know with that child’s unshakeable conviction that neither me or my father will ever, ever die.

Burl N. Corbett #HZ6518

* for more information click here

No Comments