By Thomas Bartlett Whitaker

History repeats itself; that’s one of the things that’s wrong with history.

– Clarence Darrow.

As many times as I’ve been warned to be careful what I wished for, you’d have thought at some point it would have sunk in.

In one of the many religious conversations I was forced to quietly endure while living in the Deathwatch section, a Catholic friend and I discussed the necessity of something like Purgatory if Christianity wanted to save its god from the charge of being an unjust tyrant. In one of those weird moments where a member of the flock claims absolute certainty over an issue that they cannot in reality know anything about, I was told that Purgatory wouldn’t be that bad, and that I didn’t need to worry about being sent there for a few millennia. Wanting to escape the dialogue in the least offensive way possible, I thanked this person for their concern and mentioned that Purgatory would be fine by me.

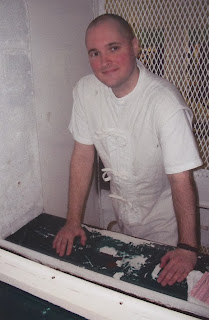

I know of no better term than that for the realm to which the penal gods have banished me. 12-Building of the Michael Unit is like a weird, three-steps-down-the-multiverse-highway version of 12-Building at Polunsky. The same cells, the same basic layout, the same filth. Familiarity lulls me into feeling comfortable for brief moments, then some idiosyncrasy catches me flat-footed and I’m left feeling bruised. Where there should be flat, white concrete ceilings in each section, here one finds skylights. Instead of thick steel bars encasing the dayrooms, here we have industrial chain-link. The guards are the-same-but-different, too: they wear the same uniforms, sport the same gas canisters on their faux-law enforcement leather belts. Their attitudes are less policy-oriented, though, less robotic. They don’t like us, exactly, but they certainly don’t hate us like they did on the Row. That may seem harsh, but I think it takes a certain type of ideological hatred to volunteer to work in America’s most aggressive death penalty machine. None of the guards here would agree to such a job; several have expressed pleasure that I “got down” on the State. The prisoners are different, too. Here we have murderers by the dozen – some of whom have cases that leave one even more confused about how District Attorneys decide which cases to seek death against – but their relationship to their crimes and sentences are very different from the guys on the Row. There’s solidarity here, but it is of a more temporary variety to what I am accustomed to. Some of these men are serving short sentences. One of the two gangsters who recently rigged their doors not to lock properly so they could attack a man being escorted from the shower is going to be paroling directly from segregation to the streets in about a month. People can be moved to other segregation units across the state at any point, so people don’t tend to form the sort of camaraderie we had at Polunsky, the sort of bond forged from living with one foot already in the grave. I’m having a hard time relating to these men. Because the environment looks so similar to the one that coiled itself around my throat so tightly for the past eleven years, I keep having these strange moments where I reach out for the crutch provided by my friends and then realize that they are 100 miles away, somewhere to the south. I don’t think I realized exactly how much I relied upon (needed? here one stumbles over the right term) these bonds to make it through each day. So much of the identity I tell myself is the center of my Me is wrapped up in the concept of self-sufficiency that I don’t think I ever allowed myself to see this truth in its entirety. And yet, if I were truly as close to perfect self-reliance as I pretended, I would not feel as I do now. I used the word “banished” earlier, and that sums it up perfectly: I was a part of a struggle. I had real friends who had passed real tests under horrid circumstances. I was supposed to be #549 on Texas’s list. Instead, my friend Rod took that distinction and now I’m just another broken primate in a cage.

I had hoped that things might be different somehow, that I might come out of the darkness automatically. I suppose I should have known that it was not going to be that simple.

My relationship to time seems to be shifting in strange and unpredictable ways. I have a calendar that allows me to see all twelve months at a glance. Before, when I looked at the year in progress, I did so with a mixture of dread and resolve. After witnessing so many of my friends marched through the appellate process, I internalized the average lengths of each phase so completely that it became impossible to look at a calendar and not automatically calculate how much time I had left before the next denial, the next disappointment. This of course culminates in the little red squares that I have drawn to mark certain dates, the days when Texas attempts to broadcast an opposing obstacle-sign to murder by committing that very act. Time therefore always feels like undertow, an inexorable force that one must constantly struggle against if one is to remain close to shore. On some level, I know that my relationship to time is different now. I still owe a death, but this is not so immediate, so deliberate, now. I should feel better about this, should be able to let time carry me along at its own pace, but I do not and cannot. As I write this – mid-April in my subjective timeline – all I really feel is an extension of the survivor’s guilt I referenced in my last essay. I don’t want to keep thinking about Polunsky. I really, really don’t. But it keeps exerting some strange kind of gravity upon my thoughts, dragging them southwards. I feel like I left comrades on the battlefield, a feeling that is so diametrically opposed to the loyalties I’ve developed during my incarceration that the overwhelming sensation pervading all my thoughts is that of betrayal. This isn’t the first time I’ve felt this way, but I had thought I’d worked some of it out of my system over the years.

One of the reasons for the concern I feel for my friends left behind is Texas’s most recent scheme to make executing people quicker and easier. I first learned of the State’s application for certification under Chapter 154 in November of this past year – only a few weeks after my arrival at Deathwatch – when the Department of Justice (DoJ) began seeking comments on Texas’s intentions. The more I looked into this, the more troubled I became, but I was sort of up to my neck in troubling matters at the time and simply couldn’t find the bandwidth to address this publicly. Over the years, I have tended to stay away from writing about the law in great detail because a) I didn’t feel I had the authority, education, or expertise needed to pen something that observers would consider to be genuinely valuable and b) I’ve never been exactly sure how to make the average person care about matters that will almost certainly never apply to them or anyone they know, especially when those matters require extended forays into some fairly boggy intellectual terrain. One thing that the past six months has shown me is that I have some incredibly intelligent readers, so perhaps I was doing you a disservice by not plunging into some of this stuff in greater depth before. Perhaps I was doing the abolition movement a disservice, too. My whole life seems to be currently constructed around making amends for past mistakes, so consider the following another attempt at righting a wrong. In any case, you truly do need to know what these rednecks are up to. It really is exceedingly foul.

So, Chapter 154: this was originally a part of the Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act of 1996 (AEDPA), a heinous piece of legislation that I have referred to numerous times in these pages. (If you care to look it up and see the actual text, here’s the link.) After the Gregg decision revived the death penalty in 1976, death sentences began to mount, especially in the South, to the tune of more than 200 per annum after 1981 and reaching 301 in 1986. Despite the butchery that followed, piously conservative politicians remained frustrated by what they viewed as “excessive appeals,” and this sentiment continued to build in popularity during the 1990s. Then right-wing terrorists blew up the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City, and the dam burst. AEDPA swiftly passed the Senate by a vote of 91 to 8, and Bill Clinton signed it into law almost immediately. People had a right to be mad at Timothy McVeigh et al., but this episode is yet another sorry example of how politicians can deftly manipulate unreflective and uninformed public sentiment towards the passage of legislation that has almost nothing to do with the catalyzing act that spawned the outrage in the first place.

This bill has contributed in major ways to the deaths of more than 1,000 human beings, including a dozen or so contributors to this site. It played a large part in killing my friend Rod a week and a half ago, in my subjective timeline. It was specifically designed to curtail appeals and limit delays by making some pretty drastic alterations to federal habeas review, such as dramatically limiting the rights of state inmates to make use of the federal courts on constitutional grounds. Remember, McVeigh and Nichols were federal inmates, so this part of the act could never have applied to them; these politicians simply pulled a fast one on the American public by pushing stories of the boogey man. For instance, I give you Senator Bob Dole: “The most critical element of this bill, and the one that bears most directly on the tragic events in Oklahoma City, is the provision reforming the so-called habeas corpus rules” (141 Cong. Rec. 15,095 [1995]). (I like that “so-called” bit, as if the writ was something only referred to by unprofessional types, rather than, gee, the only power a citizen has in the Constitution against tyranny that doesn’t involve weapons. Nice, right?) Under AEDPA, only “unreasonable” rulings can be overturned, not just erroneous or questionable ones; this is a vastly more difficult standard for reversal, meaning one can still be executed even if genuine error took place during one’s trial. You need to reread that last sentence at least once, I think, just to make sure it really sank in. Additionally, AEDPA placed sharp limits or procedural bars on the power of the federal courts to hear new factual evidence, which is why states have been allowed to execute men despite the discovery of new evidence that might – had it been allowed to develop – have exonerated them. The act also significantly reduced the time limits on federal appeals, from zero explicit limits to a one-year statute of limitations. If one were wondering why it seemed like the average time spent on death row by your typical Southern prisoner decreased drastically during the 2000’s, this act is your reason.

This is the appellate universe I toiled under, and which still obtains for all of the men currently sentenced to death nationally. Chapter 154 is a set of provisions for an even more expedited statutory scheme, one that involves something of a quid pro quo between the Federal Government and individual states that desire to “opt in” to these procedures. The deal is this: the feds will grant states a curtailed federal process if they demonstrate that their capital-sentenced prisoners have been given competent counsel. It’s an incentive, a reward, for doing the moral thing – what should have been done from the beginning. If your immediate thought after reading those last few lines was that you thought such prisoners were already granted decent attorneys, you know nothing about how we kill people in this country. Forgive me the tangent here, but you really ought to understand the basics of how these things actually work in the real world, as this goes quite a way towards explaining why Texas has executed 550 – and counting – human beings since it resumed the death penalty post-Gregg in 1982. For those of you keeping track, that’s more than a third of all executions in the modern age, and greater than the combined numbers of the next six most frequent executioners (Oklahoma, Virginia, Florida, Missouri, Georgia, and Alabama).

As things currently stand, Texas’s capital post-conviction scheme consists of two parts: a private appointment system (what existed when I went through the state courts) and the Office of Capital and Forensic Writs (OCFW), which opened its doors in 2010 – originally as the Office of Capital Writs before the expansion of its scope in 2015 lead to a name change – in an attempt to improve on the appointment system. The statute controlling state writs is called Article 11.071. Prior to the creation of the OCFW, Texas played hot-potato with the issue of who was responsible for the appointment scheme. The original wording of Article 11.071 only provided for the “appointment of private counsel,” and mentioned nothing about standards of competency. The legislature shifted the responsibility for appointing and maintaining the list of eligible attorneys from the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals (TCCA) – which had become an all-Republican outfit by this point – to eleven different Administrative Judicial Regions. This was an attempt to insulate the court from criticisms that the list was filled with attorneys who had little to no experience in capital appeals. This tactic didn’t work. Even the Fifth Circuit – the most consistently conservative federal circuit court in the nation, and one that can nearly always be counted upon to affirm death sentences – thought that this system was nearly worthless, ruling in Mata v Johnson that the TCCA had not fulfilled its statutory duty to develop standards of competency for post-conviction counsel. This failure has still not been remedied, more than twenty years later. Still, as bad as it was, the above system was at least superior to what existed prior to 1995: where, unlike in nearly every other death penalty jurisdiction, in those days, Texas did not even appoint lawyers to represent indigent death row inmates in state habeas proceedings. You might want to reread that last sentence again as well, just for fun.

Once the new Article 11.071 system was passed, it quickly proved to be a disaster. For one thing, the State apportioned almost no money to cover indigent defense, so – shock! – highly experienced attorneys generally weren’t interested. Out of 3,000 letters that the TCCA Presiding Judge Michael McCormick mailed out to lawyers from the membership rolls of the Texas Criminal Defense Lawyers Association, only about 400 responded. McCormick specifically said that these attorneys did not need any special training, instead claiming that he was interested in “people we feel comfortable with.” Sharon Keller was on the committee tasked with applying this “good feel” standard to potential capital counsel, so perhaps one could be forgiven for suspecting that what the TCCA was really interested in was a collection of attorneys who were pliant, inexperienced, and, frankly, not on the same intellectual plateau as appellate counsel for the State. All told, attorneys’ fees were capped at $7,500 at $100 per hour, so inexperienced is exactly what they got. This funding only managed to cover 180 of Texas’s 414 death sentenced inmates. Either math was not their strong suit, or the entire project was a farce. You judge.

Then Congress passed AEDPA. Despite Judge McCormick going on record to state that Texas’s appointment system was not perfect and that there was “a lot missing and I don’t have the answers,” Texas immediately invoked Chapter 154’s expedited procedures. These include a reduction in the time allowed to petitioners to file their federal writ applications to 180 days after the termination of state court proceedings, a requirement that the federal district courts render a final determination on the writ petition within 180 days of filing, and a limit of 120 days after the last responsive brief for the circuit court to issue a ruling. What this means is that a petitioner would likely spend less than two years in the federal courts before entering the Supreme Court (SCOTUS). To put that in perspective, for those of you who read my treatment of Jeff Prible’s case (which is about to get really interesting, by the way), rather than his attorneys having discovered a massive operation to manufacture guilt by one of America’s top prosecutors, the State would have killed him more than ten years ago. Anthony Graves would also have been murdered before he could prove his innocence; same with Alfred Brown. I almost certainly would have been killed back in 2012 or 2013. I clearly needed every minute of my eleven years on the Row to put together the operation that secured my clemency; I simply wouldn’t have been able to amass the ammunition I needed to take aim at the Governor. Chapter 154 is a true killer, in every sense of the word.

Fortunately, the federal courts rejected Texas’s first attempt to opt in to Chapter 154’s scheme, specifically calling out the TCCA for failing in its statutory responsibilities to develop standards of competency for capital post-conviction counsel. The TCCA subsequently promised to develop “written standards for habeas lawyers,” then managed to fail spectacularly at this task numerous times until December 2006 – mere months before my arrival on the Row. How hard can it be to say: “Since we are going to try to take your life, Mr Capital Litigant, here’s an attorney who’s actually in good standing with the state bar”? I mean, I just wrote that in ten seconds. But they couldn’t even manage this because, once again, judges in Texas are elected and these Repubs had an ass-backwards primary electorate to placate. They eventually resorted to 48 involuntary appointments of attorneys, some of whom had zero post-conviction experience, while others had significant disciplinary sanctions. (For a good example of this, read the 12 June 2000 article in the Chicago Tribune by Ken Armstrong and Steve Mills titled “Gatekeeper court keeps gate shut.”) Things got so bad that the TCCA had to appoint three former staff attorneys to ten cases, even though Judge Baird admitted that the court “knew that these law clerks had little if any experience representing clients in habeas proceedings.” One of these attorneys represented Napoleon Beazley. This attorney later admitted that he failed to do critical work, including talking to Beazley’s two co-defendants. Had he done so, he would have discovered that both co-defendants had made undisclosed deals with prosecutors to help persuade Beazley’s jury to sentence him to death. On 28 May 2002, Beazley was executed in Huntsville. He was a minor when he committed his crime, so had this TCCA hack done his due diligence and managed to keep his client alive until 2005, the Roper case would have changed his sentence to life in prison. Barring some unforeseen health crisis, Beazley would still be alive today. Napoleon Beazley is just a name to me and you, but I’m sure this is no small matter to his family; I’m certain his mother would have appreciated even the tiniest bit of effort from the attorney tasked with saving her son’s life.

In a normal state, the above would have surely necessitated some changes by the legislature. It’s not as if there wasn’t a steady stream of news articles berating the TCCA for its jurisprudence on these matters. Nevertheless, the politicians remained quiet, and the TCCA, if anything, grew more bold. For instance, in 2002 the TCCA declined in Ex parte Graves (and yes, it was that Graves) to set standards for granting competent, dedicated, knowledgeable counsel to death-sentenced prisoners (70 S.W. 3d 103 Texas Crim. App. 2002). In fact, they openly stated that there would be no remedy for inmates who received incompetent counsel because – get this – the competency of an attorney is not apparently measured by what that lawyer actually does for his/her client (what we might think of as the substance of that representation), but rather by the fact that the TCCA approved the attorney to be on the list of acceptable counsel to take the case in the first place. They were competent, in other words, because the TCCA said they were, period. You might laugh, but this actually seemed logical to Republican voters. This actually killed people.

In 2007, the Texas Defender Service issued “Moving Forward: A Map for Meaningful Habeas Reform in Texas Capital Cases,” a follow up to their 2002 study “Lethal Indifference.” In a detailed review of 376 writ applications, the 2007 article reports 28 percent of petitions presented zero extra-record claims, and 38 percent failed to include any extra-record materials – a clear sign the attorneys filing them had spent little to no time researching their cases. Numerous reporters feasted upon this study like the vultures they are, and discovered – again, shock – that Texas’s capital scheme was still broken. The TCCA, once again, promised to fix the problem. They formally adopted a method for removing lawyers from the list of attorneys they had hand-picked to represent capital litigants, if these attorneys had been found by a court to have engaged “in a practice of unethical or unprofessional behavior” or been found to “have rendered ineffective assistance of counsel.” This last part is a bit of a joke, since the TCCA is the court that would have to make this ruling in the first place, and I’ve never seen them do so. Remember, under AEDPA, the feds have to give deference to prior state decisions, so it’s nearly impossible for a federal judge to sanction an attorney if the TCCA has already approved of their work. In essence, they had the list of attorneys they wanted to work with and were simply acting to protect the integrity of the lethal conveyer belt they had spent decades designing and implementing. And why wouldn’t they want to maintain the status quo? In 2006, the year this openly pro-prosecution court “changed” the rules, Texas executed 25 inmates. Everything was working exactly as they wanted it to.

The group of legislators elected in November 2008 was the most moderate (for Texas) in almost two decades. During the legislative session the following year, they established the Office of Capital Writs (which, as mentioned earlier, later became the OCFW). This all occurred too late to help me, as I had already been shouldered with the burden of working with an attorney who proved to care little for my ultimate survival. OCFW operations began on 1 September 2010, but they did not accept a client until the end of October, if I remember correctly. Its initial Director was a legitimately qualified and experienced attorney, Brad Levenson – though his experience was all gained in California, where capital litigants face a vastly more friendly jurisprudential landscape. His staff, on the other hand, had little to no experience in capital work, and they were chronically underpaid to boot. I don’t believe they secured any reversals during Levenson’s five or so years as Director, but they did succeed in obtaining evidentiary hearings in many cases and managed to drag out the state appellate process for their clients throughout this time. However, the TCCA, tasked by the legislature with awarding appointments to the OCFW, chose not to reappoint Levenson at the end of his term – no doubt because he had the temerity to actually fight them on numerous issues. This cowardly move surprised none of us on the Row. Levenson’s replacement, Ben Wolff, had a grand total of one year working as a staff attorney at the Texas Defender Service. The TCCA approved him quickly despite the fact the legislature, which specifically wrote the rules governing this position, required an applicant have at least three years’ experience in post-conviction work. The current legislature is vastly more conservative than the one that created the OCFW in the first place, so I suspect the Texas Tribune was correct when they argued that Wolff’s appointment was an underhanded attempt to make the OCFW ineffective.

As things stand, the OCFW is still staffed almost entirely by lawyers right out of law school. There are currently eight staff attorneys, the average salary for whom was $70,837 for 2017. The office is currently handling roughly fifty cases, meaning that at various points each attorney might have to juggle as many as fifteen cases at once, a load that Texas had the gall to label as “modest” in their Chapter 154 application in 2013. Staff attorneys average between 60 and 80 hours per week. The turnover rate is therefore predictably high. In fact, none of the attorneys who worked for the OCFW when Texas filed its renewed Chapter 154 application in March 2013 are still with the office. When the Federal Public Defender Offices opened their Capital Habeas Units recently, the OCFW lost 37 percent of its attorneys and one mitigation specialist. The budget for investigations is even worse: I don’t have the exact figures for this (I was told the office wouldn’t give them to me), but several attorneys admitted that witnesses are regularly not called to court and mental health consultants are not hired, due to lack of funding. As I write these words, the office appears to be on the verge of collapse.

Given all of this, you may be asking how on earth Texas ever thought its Chapter 154 application would be approved, especially considering its prior attempts had been rebuffed. That was one of my questions when I started looking into this. The answer is essentially this: elections have consequences. As part of the USA Patriot Improvement and Reauthorization Act of 2005, Congress shifted responsibility for determining which states met the certification requirements away from the federal courts and into the hands of the United States Attorney General. The DoJ under Bush the Younger published new rules to govern this process, but they never went into effect and were eventually withdrawn in November 2010. The DoJ published a second notice of rulemaking in March 2011, and then a final rule on 23 September 2013. Attorney General Holder managed to sneak in two changes to these rules that, at the time, may not have mattered much because he was never going to certify a Southern State. These dealt with a decision that rulemaking determinations would be treated as “orders” (and therefore not subject to Administrative Procedure Act rules), and that certification decisions would be made based on information privately collected from state attorneys general. Texas applied for opt in treatment, and then was promptly ignored by Obama’s DoJ for the remainder of its term. The message was pretty clear: you redneck wackos must be joking.

Alas: Trump – who promptly gifted us with one Jefferson B. Sessions. On 16 November 2017, Sessions published notice of and sought comment on Texas’s stalled application, which, up to that point, no one outside of the DoJ even knew existed. On the same day, the DoJ asked Texas’s (currently criminally indicted) Attorney General Paxton if all of his previously submitted materials were still up-to-date. Texas amended its application on 18 December 2017. Obviously, Sessions is the chief prosecutor for the country, so it may seem off to you that he – a man who operates under structural, institutional bias against criminal defendants, and not an impartial arbiter like the courts – should get to rule by fiat on such an important matter. This would be problematic under any Attorney General, but Sessions is a weapons-grade moron. During the debate over the USA Patriot Act amendments, then-Senator Sessions testified that federal habeas needed to be “tighten[ed] up” to address “abuses in the system.” He apparently believed that the role of the federal courts in reviewing habeas petitions was simply to “review the trial record to see if the person got a fair trial.” A first-year law student could have pointed out to him that it would be nearly logically impossible to fashion a description of the writ that was more packed with error: habeas proceedings by definition involve, primarily, evidence outside the trial record. That’s the whole point of them, the reason they exist in the first place.

It gets better. A memorandum on Sessions’ decision to revive the opt in process indicated that he planned to consult the Capital Case Section of the Criminal Division – a part of the DoJ that prosecutes federal capital cases and defends against habeas petitions. When criminal defense groups opposed to Texas’s petition for certification requested (via the Texas Public Information Act) access to communications between Sessions, the Capital Case Section, and the Texas Attorney General’s office, these requests were denied on the basis of “attorney-client privilege.” If Holder had done anything remotely this underhanded with, say, the Attorney General’s office in California, Rush and Hannity and the rest of their gasbag friends would have had a collective embolism. Just saying.

Once you get into the substance of Texas’s application, you see just how disingenuous this whole situation is – and why I felt compelled to do the research I’ve laid out for you here. For starters, Texas’s application was submitted in March 2013 – six months before the DoJ’s final set of rules governing the Chapter 154 process were published. It is therefore unsurprising that Texas’s appointment scheme fails miserably to meet the standards outlined by the Federal Government. In fact, despite a bold assertion in the cover letter that the “application demonstrates that Texas satisfies all of the statutory criteria for certification,” it doesn’t bother to address a single one of the DoJ’s grounds for certification. Even when given a chance to amend their application in December 2017, they fail to do so. Instead, they simply claim they are good on their end of the quid pro quo – and have been since 1995! Texas focusses on the creation of the OCFW, but conveniently negates to mention that this office didn’t even exist until 2010, a full fifteen years after the period for which it is seeking retroactive certification. The Texas Attorney General’s office also claims that all the attorneys seeking to join the Article 11.071 private appointment list are required to undergo “a rigorous screening process established by the Office of Court Administration [OCA].” One problem: many of the practitioners on that now infamous list never went through any OCA screening process, and these “rigorous” standards apparently don’t include American Bar Association (ABA) censure – a mark that at least four of these attorneys have on their records.

There’s also an argument to be made by better legal minds than myself that Chapter 154 violates the separation of powers doctrine. According to my understanding of Plaut v Spendthrift Farm, Inc (514 US 211, 218-19 [1995]), the Constitution “gives the Federal Judiciary the power, not merely to rule on cases, but to decide them.” I think Chapter 154 messes up this balance of allowing courts the time needed merely to rule on cases, not decide them. This seems like a semantic game – and it would be in the world of normal conversation – but these words have special meanings under the law. Under Chapter 154, Congress is approving a rule of decision but then preventing the courts from applying it, since they don’t have the time under this statute to truly decide cases on their merits. One 2007 study I located found that, on average, a period of 1,152 days was needed for federal district judges to work their way through each case – more than 2.5 times the maximum allowed by this provision. Judges will simply be left making judgements on the fly, without ever really getting to learn anything about the cases they are ruling on. Congress isn’t allowed to restrain the judiciary like that. We see these things in Turkey and Hungary, but they aren’t supposed to happen here.

The absolute worst part of Texas’s application is that it is demanding certification be granted retroactively, all the way back to 1995. This would mean dozens of inmates in Texas would have their federal appeals rendered untimely and therefore procedurally barred, and the rest would have their options minimized. Under the current statute, a defendant has twelve months to file their federal writ applications. So, say you (or your friend, or your son) are eight months into this window, and Sessions grants Texas’s application retroactively. This immediately changes the timeframe allowed to file the writ to six months – a deadline now missed. This means there’s no federal appeal. The only review will be the rubber-stamping process perfected by the TCCA. Which, let’s be frank, is more or less exactly what Texas Republicans want: the “swamp” of DC “drained” from their autonomy. Everything in their application makes sense when you look at it through the lens of politics. I now have a lifetime to keep banging my drum on this point, so I might as well take the opportunity to deploy it again: the death penalty is a political sentence. All you need to do is look at the statistics of who uses it, who favors it, and who opposes it, to see this.

So, that’s what the Yee Haw Republic is up to at the moment. In response, the Texas Defender Service and lawyers representing a number of Texas death row inmates have sued Sessions in an attempt to have Chapter 154 ruled unconstitutional. I’ve read the petition they filed in DC Circuit Court and they seem to have the weight of evidence and reason on their side – but since when has “reason” had any impact on the motley band of corrupt buffoons our president has elevated into power? I honestly don’t have any sense about how this is going to turn out. A lawyer friend of mine doesn’t think it will become law. It’s all in Sessions’ hands, though, and there isn’t a metaphor currently within my grasp that adequately summarizes how little I trust him to make a wise decision. I’ve located nothing in my research that would indicate a process of decertification if the DoJ ultimately grants Texas’s request, meaning there isn’t much that any of us can do about this at the moment, in a direct sense. Problems like this are created and solved at the ballot box. So, if criminal justice reform is one of the issues you care about, you need to consider very strongly joining the so-called “Blue Wave” that the punditocracy claims is heading for these Trumpian shores. I actually know some anti-death penalty types who voted for Trump, and I hope that they are starting to see that this idiot’s choices are killing the people they claim to care about. You at least have an outlet for redeeming yourselves, or for venting your frustration. I’m obviously somewhat more limited. For now, all I can do is write about these things and pretend to myself that resistance always means something, even – especially – when it feels like one is barely holding steady against a very strong current.

I think my relationship to resistance might be shifting, as well. Death penalty trials cleave your sense of responsibility into separate portions. On the one hand, you feel the weight of your guilt pressing down upon you. This force obviously requires that one feel some form of punishment is necessary if redemption is ever to be obtained. The State claims that the only fitting punishment is your end, that redemption is not the goal of justice, but vengeance. This is a leap though, one powered by ideology. It isn’t obvious or logical that this be the only means of providing justice, or the vast majority of nations on the planet wouldn’t have left the penalty behind. There are all kinds of punishments that fit on a spectrum of possibilities; death is only the most extreme. Sitting on top of all that is one’s memories of one’s trial, and all the ways the State used power, deception, and rhetoric to convict you. The most overwhelming emotional memory I have of my own trial was not the verdict or sentence, it was the sense of wrongness over how the trial was conducted: I simply couldn’t believe that people lost their lives in this country over such a pathetic, silly, almost completely fact-free process. After such a spectacle, you are left in a conundrum: you desire justice for your crimes, but you also need for justice to look less like a particularly poor local amateur dramatics society production of a Noël Coward farce, less like a whore dressed up in stolen black robes. You want justice for justice as a concept. There’s obviously some irony there, and the State takes full advantage of this if one dares to speak about the tawdriness of the thing. This is the root of the various activities that defined my resistance over the years. So long as I was living under a sentence of death imposed by a kangaroo court, I couldn’t stop tonguing the ulcer, so to speak. It simply wouldn’t heal. It simply wasn’t right.

Now that I’m no longer on the road to the medicalized gibbet, I feel a sort of shift in the works. The other form of responsibility/guilt seems more primary. It was always there, though I mostly dealt with it in private. (I keep getting criticism from people for not describing this internal process in the public sphere, and this has always seemed weird to me. Who are you to demand such a thing? Under what right? Voyeurism cheapens both the watcher and the watched, you know.) I’m trying to figure out the appropriate manner and degree of resistance now that I have a new home. Obviously, I wouldn’t have spent nearly 200 hours researching something as ghastly and idiotic as Texas’s Chapter 154 application if I had any intention of allowing the State to blatantly spread outright falsehoods. I wouldn’t have any claim to have developed a moral conscience if I permitted such propaganda to be promoted without confronting it. But I also need to calculate how much suffering I need to patiently accept as my due now that an unjust sentence has been replaced with something a bit more fitting.

I’m obviously still working this out. I think they’ve sent me to the right place to conduct this experiment. I said something in my last essay about how I suspected the system was going to test me before they released me into population. I’m starting to think this might have been naïve: it’s starting to seem like they would be content to leave me back here to rot for the rest of my natural life.

I know some of you are going to want an update, so I might as well squeeze this in here. On 5 March, officers woke me up at 2am in my cell at the Byrd Unit and ordered me to pack my few belongings. While I was in Huntsville, numerous officials promised me that as soon as I reached my assigned unit, they would release me into the general population. Instead, for reasons that are still murky to me, I was returned to ad-seg and placed on F-Pod. On top of this, they are moving me to a new cell every Monday, Wednesday and Friday. As I write these words, I am now residing in my 18th cell at the Michael Unit. As a point of reference, it took me 92 months to reach my 18th cell on the Row. Three other men are similarly included “on rotation”; all have been involved in active escape attempts and have “Security Precaution Designator” tags. The message seems pretty clear: some REMF way up the food chain views my commutation as an escape from justice. According to TDCJ’s “Admin-Seg Plan,” I will meet with officials from the State Classification Committee (SCC) “60 days after [my] first 7-day review,” which falls on 11 May. I have been documenting the manner in which I was placed in solitary, though I really don’t have any idea yet if this will matter. Thus far, policy seems to matter in population about as much as it did on the Row: only when it benefits the State. [Late note: As of 23 May, I still haven’t met with SCC, and no reason has been offered for this policy violation despite my repeated requests for information. I’m glad I wasn’t holding my breath.] [Later note: I’m now scheduled to see SCC on 14 June. Wish me luck!] [Latest note: SCC denied my release to the general population. My next meeting with them will take place in December, or so they claim. There’s a lot to add here, but I probably ought to save this for my next essay. Sigh.]

I had hoped that I would be able to relax and soften my shell a little bit once I arrived at my ID Unit. (That’s what they call the serious units, apparently; the acronym stands for “Institutional Division.” So, there’s your prison term for the day.) That’s not going to be possible here. This place is far more violent than Polunsky. I’ve mentioned before that officers had told me that Polunsky’s 12-Building was one of the more sedate segregation facilities in Region 1. I can now verify this claim. Here, five pods (A through E) are currently setup for some sort of bizarre “mental health program,” and they keep the Extraction Team humming along all day, every day. I haven’t really been here long enough to write about this coherently. However, I’ve been planting MB6 seed all over the place, so I hope to be able to find someone who can write about this program in an authoritative way. From this remove, it sure seems like yet another attempt by the system to pretend it is reforming itself, sans any of the actual moves required by genuine reform. From here, it sure looks like they just wanted to collect all of the violently insane offenders in northeast Texas in one place, so they could benefit from the economies of scale. F-Pod is therefore the only true admin-seg wing in the facility. It contains the worst-behaved 84 scamps in the joint, supposedly. I’m one of only a few non-gang members present, and certainly the only prisoner who hasn’t committed violent acts against staff or inmates in recent memory.

I arrived to find 2-Section (the naming conventions are wacky here, so this is what was called B-Section at Polunsky) on fire. Apparently lighting one’s mattress up and shoving it out the bean-chute is the cool thing to do in these parts, especially if you can then back this up by launching projectiles at any lawman attempting to put out the flames. Points are awarded for this. A bottle to the head is considered a homerun. Seriously, I’m not kidding, they bet on this sort of thing. Igniting state property is the one surefire (sorry) means of making a sergeant come to the pod, so it’s pretty much a daily – if not hourly – occurrence. These doors have vulnerabilities, especially the aforementioned chutes. Many of us figured out how to pop them open at will on the Row, though this was seldom done because if you got caught you received a 90-day all-expenses paid trip to F-Pod as your reward. But since this is F-Pod and there’s nowhere left to send any of us that could possibly be considered worse, the chutes pretty much stay open all day. It certainly makes trafficking and trading easier, let me tell you. The officers stationed on this pod all have very active imaginations; they need them, what with all of the pretending they are forced to do, all day long, that they can’t in fact see that none of us are “secure” in the technical sense.

There’s a lot of “family” (i.e. gang) politics at work here. People – especially the whites – kept asking me loaded questions during my first few weeks, trying to figure out whether I was a supremacist or a separatist, as if those were the only two responses to the race question. I got tired of this nonsense years ago, so I just started making gangs up: Tyger Tyger, Paravins United, Schreibtischtäter. Nobody in my first section caught the joke, but my second neighbor – head of MS-13 here at this unit – started cackling when I told him I was a Captain in the Kim Jong-un Mafia. His neighbor didn’t get it. “He’s telling us to mind our fucking business, ese,” the first responded, before giving me a dead-eye stare. “Fair enough,” he answered at last. And that was that.

It hasn’t been all bad. One day I will have to write about the “grill.” I can’t do it now. However, know that this feat might just be the Mount Everest ascent in the Himalayan range of contrabandosity. When I told my dad and step-mother (still on the other side of glass, alas) about what I had created, they both nearly fell out of their chairs laughing. Also, at the rate they are shifting me around, I will have given the entire pod a Level 27 OCD Grandmaster cleaning within a few more months. These cells certainly need it.

Even with all of the violence I’ve witnessed here, these are still problems I want all my friends on the Row to have, because they are live-person problems. For those of you who witnessed certain unnamed personages give nice little performances on the news hyperventilating about how the State needed to kill me so that society might be safe, I hope you’ve noticed that the world hasn’t changed for the worse since 22 February (at least not in any way that’s attributable to moi, I mean… I have no idea what our Idiot-in-Chief is going to have done to the world between when this was written and when it is published, but I’m not taking any credit for that circus). The world wouldn’t be any less safe if the rest of the guys on the Row had their sentences commuted, either, nor more secure if Chapter 154 were to become the law of the land. See the lie. Call it for what it is. I happen to think the Blue Wave is going to be a lot smaller than some people do, so get out there and participate. None of this is going to get any better unless you – yes, YOU, the person reading the screen right now, not some generalized “you” that you can deflect off onto the crowd – get involved. History may repeat itself, but that doesn’t mean it has to.

My thanks to Linda H. at The Prison Show for helping me compile some of the research I used to write this article

|

| Thomas Whitaker 02179411 Coffield Unit 2661 FM 2054 Tennessee Colony. TX 75884 |

Thomas’s Amazon Wish List

Donate to Thomas’s Education Fund

6 Comments

MV

February 10, 2019 at 8:08 pmThank you for taking the time to write this blog. Your wit is beautifully woven into the eloquent (and informative) peice that you crafted above.

Also, I’m really touched by your resilience, and your desire to stay alive for your dad. Having only learned of you this morning via a random YouTube recommendation, I feel grateful to have the opportunity to learn about you beyond the superficial, news level. It’s touching to know that your visits with your dad and step-mom are filled with laughter and joy. Amazing how compassionate and loving parents can see beyond the mistakes that children make.

I won’t wish you and Hope filled comments because I see your potential to survive without anyone’s pity. Therefore, I’ll rest-assured that you’re doing okay, and coping with life as best as you can, just as we all are. And 2 hours of my morning spent invested in your story are something I’ll always carry with me— so please remind yourself, in those low moments that we all have; that others see the beauty and good in you, in-spite of the difficulties you’ve overcome. You’re appreciated for the effort and love applied to this blog, and for simply staying alive and being you.

Much love,

MV

Lindsey

September 2, 2018 at 5:15 pmThomas, were you on deathwatch with John Battaglia? You were both scheduled to be executed in February, so I figured you might have spent some time w/him. I saw an interview he gave a while back with Execution Watch and you'd have thought he was just shooting the shit w/someone at a bar, with the way he seemed so blase about it all. Was wondering what you thought of him.

I'm glad you've been commuted, where you are now seems much less boring. I don't agree w/the conditions on TX death row. I also think death row inmates should always have access to competent attorneys. "The right to an attorney" doesn't mean much if the attorney is inept, inexperienced or is a bad apple, IMO.

Joe

August 29, 2018 at 12:41 amIt's always great to hear from you Thomas. I've checking every day, sometimes several times a day, to see if you have a new post.

I hope your 'housing' situation improves as soon as possible.

Still eagerly awaiting the next NMFD installment.

Thanks again you for what you do here.

TC27

August 28, 2018 at 1:24 pmI read 'Executed on a technicality' on Thomas's recommendation so the bizarre limitation on federal HC appeals is not news to me. I think whatever your moral views on the death penalty the fact that citizens can be killed by the state without effective due process should be enough to convince every rational person to oppose capital punishment.

I know the letters lag somewhat so hopefully Thomas has being moved out of adseg by now.

MV

August 27, 2018 at 5:02 pmThank you for taking the time to write this blog. Your wit is beautifully woven into the eloquent (and informative) peice that you crafted above.

Also, I’m really touched by your resilience, and your desire to stay alive for your dad. Having only learned of you this morning via a random YouTube recommendation, I feel grateful to have the opportunity to learn about you beyond the superficial, news level. It’s touching to know that your visits with your dad and step-mom are filled with laughter and joy. Amazing how compassionate and loving parents can see beyond the mistakes that children make.

I won’t wish you and Hope filled comments because I see your potential to survive without anyone’s pity. Therefore, I’ll rest-assured that you’re doing okay, and coping with life as best as you can, just as we all are. And 2 hours of my morning spent invested in your story are something I’ll always carry with me— so please remind yourself, in those low moments that we all have; that others see the beauty and good in you, in-spite of the difficulties you’ve overcome. You’re appreciated for the effort and love applied to this blog, and for simply staying alive and being you.

Much love,

MV

Hatful of Hollow

August 26, 2018 at 8:43 pmThis comment has been removed by a blog administrator.