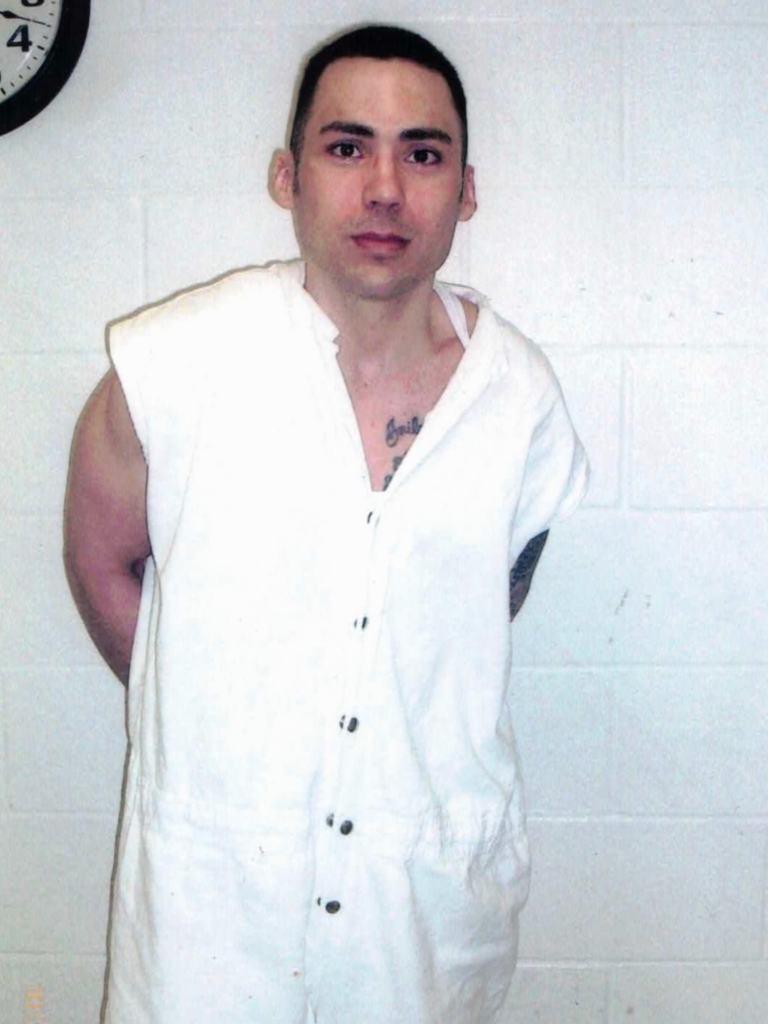

Quintin Jones aka “GQ” (Executed: May 19th, 2021)

GQ, John Ramirez (aka Rambo) and I lived on Death Watch – where the State of Texas stores its inmates once the courts issue an execution date – in cells next to each other for the last three months of GQ’s life. When I think of him all of my memories are woven around our combined banter with each other. That’s how I want to share him with you.

30 days from execution

GQ: Billy, this drank [prison wine he made himself] is off tha chain. It is sssuper duper ssstrong.

Me: Did you just say “super duper”? You’re from the ‘hood, right? Ya’ll say that in the ghetto?

GQ: Nah, I sssaid sssupa dupa – not sssuper duper. And I better not ssay eitha in tha ‘hood.

Rambo: He said super duper, don’t let ‘im sell it. He’s been writing a bunch of white folks.

Me: We’ll turn you into a proper cracker.

Rambo: A supa dupa cracker.

GQ: Ssshut up, Rambo.

A few minutes later

GQ: I ssshot myself in tha chest ooone time. That was tha last time I ssshot myself.

Me: That’s usually the last time anyone shoots themselves, GQ.

Rambo: I didn’t expect ya’ to say that… What’d you shoot yourself with?

GQ: A fffourty-five.

Rambo and me in unison: DAMN!

Rambo: You must’ve wanted to die supa dupa bad.

GQ: Yeah.

Me: Why’d you do it?

GQ: (He replied in a soft voice with his ever present slight stutter.) I was only ssseven-teen but I was sssick of bein’ a dope fiend. I was assshamed and didn’t wanna live.

Rambo: What went down that day?

GQ: I was at tha house alone, lookin’ at my pistol, wonderin’ iiif’n my pain would eva end and… and… why was I eeeven on this fuckin’ pplanet if all I’d eva’ be wwwas a fucked-up dope fiend. Words my mmmom sssaid to me ova and ova as I grew up kept goin’ ttthrough my mind… “I hate you, I wwwish you’d neva been born!” As those words twisted in my mind, I put tha barrel against my ccchest and sssqueezed tha trigga… (He paused for a long time here. When he paused, I was imagining that I could see through the thick concrete wall separating our small, hard cells and see his face. What pain was etched into it? Was any showing on the surface, or was it all captured in his words? Was the short, muscular, black and handsome GQ standing straight and proud, like usual, or did this heavy memory weigh him down enough to bow his back as his words were doing to my heart?) The ssshot knocked me across tha room and I woke up later, bleedin’, hurtin’ like a motha’ fucker… and alive. I cccrawled to tha phone and called a family member. All I had’a sssay was “I dddid it again.” They knew and called an ambulance. When I got outta tha hospital I went into a sssypschiatric hospital for a month.

Me: Did that help at all?

GQ: Nah, tha day I got out I went ssstraight to tha dope house and got high.

Rambo: Was it some good shit?

GQ: Ssshut up, Rambo.

Rambo: What was the deal with your momma?

GQ: Mmmy twin brotha and I ssshe treated like that. Ssshe told us we’d ruined her life and ssshe wished we’d neva been born. Ssshe didn’t treat her otha kids that way.

Me: How she treated you still fucks with you, huh?

GQ: Yeah.

Rambo: Have you forgiven her?

GQ: Yeah.

Me: Seriously?

GQ: I’m on tha Row for killin’ my great aunt when I was strung out on tha H [heroin]. Her sssista forgave me and has kept in touch with mmmee all these years. Ssshe is in her nineties now and is tryin’ to get tha Ssstate not to kill me ‘cause ssshe forgiven me and loves me… and doesn’t want mmme to dddie. (GQ choked up here and paused to regroup.) I took away her sssista, her best friend, ssshe’s had to live tha past twenty years aaalone ‘cause a me… Yet ssshe forgave me. Ssshe not only forgave me, but loves me. Ssshe taught me to forgive my mmmom.

Rambo: You forgive yourself?

GQ: I don’t know if I’ll eva ggget there.

Two weeks before execution

At 6:00PM, a five-foot-two-inch, two-hundred-pound-plus, middle-aged guard named Nelson walked past our cells doing a security check. Once she passed through the section, the following conversation ensued.

GQ: Ol’ Nelson iiis lookin’ good tonight.

Me: Say what? You drinkin’ again, Q?

Rambo: You must be drunk, homie.

GQ: Ya’ll are just haters.

Me: Tell me how you’d try to pick her up if you were free and ran into her.

GQ: (Using a sing-song voice similar to Mickey Mouse) Hey, big momma, wanna go get some chicken nuggets? I’m buyin’. And maybe later I’ll give you a supa dupa surprise.

Rambo: He’s takin’ her to McDonalds!

Me: Yeah. Her supa dupa surprise is a Happy Meal.

Rambo: She’ll call it a nugget, too.

GQ: Ssshut up, Rambo.

Rambo: Did you notice every time he does that voice he never stutters?

Me: Shut up, Rambo.

GQ: (A few minutes later.) I’ve got a question for ya’ll. When someone aks me how I’m doin’, would it be wrong to tell ‘em I’m fucked up right now?

Rambo: Nope.

Me: Depends. Is it someone who cares that’s asking, or someone who’s asking you know doesn’t really give a shit?

GQ: I’m talkin’ ‘bout my homies who really care. I don’t wanna put my ssshit on them and ssstress ‘em out… I just don’t wanna mmmake ‘em feel bad.

Rambo: If ya don’t stay real with them, they’ll feel worse ‘cause they’ll think you pulled back from them in the end and they couldn’t reach ya. They’ll feel they lost ya before you’re even gone.

GQ: Yeah. Next time Eddie Lee cccalls ova here and aks me hhhow I’m doin’, I’ma tttell ‘im that I’m fucked up right now, but I’m gonna make it.

Rambo: Eddie Lee will get it.

Me: For a gangster type, the dude’s got a heart.

GQ: Yeah, he does. Ya’ll know the sayin’… hold up, I gggot it right here. (We could hear a brief shuffling of paper as he found the one he wanted. Then he cleared his throat.) Pppeople will not care how you feel until they fffeel that you care. People wwwill forget what you sssaid. People will forget wwwhat you did. But, people will nnnever forget how you make them feel.

Rambo: That’s what got you thinking about how to answer the ‘How are you doing’ question?

GQ: Yeah. I know tha aaanswer, just wanted to be sssure.

One week before execution

About thirty minutes after GQ returned to his cell from a media interview with a New York Times reporter, the following took place.

Me: How’d the media visit go?

GQ: It went real wwwell.

Me: That reporter made your ass cry, didn’t she? Don’t lie.

Rambo: You were down there on camera blowin’ snot bubbles, huh?

GQ: (Laughing.) Ssshut up, Rambo… But yeah, like a motha fucker. Ssshe got me talkin’ about my aunt and that was it.

Me: When will the interview be online?

GQ: I ain’t sssure but I ttthink this interview, and one my great aunt did, will be ssshown to the Clemency Board [Texas’ Board of Pardons and Parole]. That might help my chances.

Rambo: What do you think your chances are for clemency – to get life without parole, instead of getting murdered by the State?

GQ: Two months ago, I thought I hhhad no chance. Now, I ttthink I gotta a sssupa dupa chance. I’m gettin’ a sssupa dupa lot of…

Rambo: Ease up on the “super duper.” You’re over doin’ it, homie.

GQ: Ssshut up, Rambo. I’m gettin’ a lot of sssupport from freeworld people – ova one hundred thousand sssigned a online petition to sssave my ass ssso far. Sssome cccelebrities too. My great aunt has begged the Board to lllet me live. Iii think I’ve got a good chance. A sssupa dupa chance.

Me: You added that last “super duper” just for Rambo, huh?

GQ: (Laughing.) Yep.

Me: Dude, you’re not a bad person. If I had to use one word to describe you it’d be Genuine – Genuine Q. You’re not a shucksta motha fucka playin’ being sorry, and you’re not a future fuckin’ danger. If these people have a clemency system, then it’s for someone just like you. I hope you get it.

GQ: Thanks, Billy. I hope I’m around on the 20th too. Iii’ll holla at ya’ll later. Iii gotta go boom boom.

Me: What? What the hell is “boom boom”?

Rambo: Yeah, are you going to play some drums?

GQ: I gotta take a shit!

Me: I don’t even want to know how you came up with “boom boom” to mean takin’ a shit.

Rambo: He got that from white folks.

GQ: (Laughing.) Yep.

Two days before execution

I was just lying down to go to sleep when GQ came back from one of his last visits. He was put in the dayroom, and from my lumpy mattress I heard him tell everyone: “The Clemency Board ssshot me down bbby a three-to-four vote. Mmmy only shot now is tha Sssupreme Court givin’ me a ssstay, or Governor Abbott grantin’ me a reprieve.”

Fuck, I thought. Fuck Texas.

One day before execution

Me: How are you doin’, GQ?

GQ: I’m fucked up right now, bbbut I’m gonna make it.

Me: If ya don’t, a lot of people are going to be fucked up about it ‘cause a lot of people care about you. You must’ve made people feel like you care.

GQ: Why do you sssay that?

Me: ‘Cause the past two nights I couldn’t sleep for shit, so I got up and put on the Tank [Polunsky Unit’s radio station]. Both nights the inmates hosting the shows were reading shout-outs for you from your friends on the Row. I’ve never heard anyone get love like that.

Rambo: They’ve been given that fool love all night long the past few days. I’ve never heard someone get love like that either.

GQ: I heard ‘em too. Iii can’t lie, it made me tear up.

A couple of hours later

GQ: Billy, do you think I’d be wwwrong if on my lllast day I told everyone wwwho wanted to vvvisit me that I’d rather not have any visitors that day? I just want to ssstay back here with ya’ll, where I feel more comfortable.

Me: Nah, I don’t think that’s wrong. Anyone who loves you will want you to be as comfortable as possible. Just tell them what you told me, they’ll understand.

GQ: You don’t think they’d be hhhurt? It’s just that I’m inssstitutionalized. I feel mmmost comfortable around ya’ll on tha Row. We can all kick it, joke and ssshit. If’n I go to tha last visits, it’ll be emotional and I dddon’t wanna deal with that my last ddday. It’ll be hard enough.

Me: Talk to your people like you just did with me.

GQ: I’ma do that.

Day of execution

The prison was utterly silent. Only a couple of security lights were on to illuminate the stark setting – the hard, cold, black bars and cracked concrete – that made up the maximum-security prison. The wing Death Watch is on wasn’t cold this day, but it made me feel cold inside – like ice had formed inside of me. I shivered involuntarily before mentally shaking it off. I’d just finished exercising when through the silence I heard GQ shuffling things around briefly in his cell. Wanting to say goodbye, I found myself standing at my cell door being haunted by this unnatural place on this unnatural day.

Me: GQ?

GQ: What’s up, Billy?

Me: Just wondering how you are is all, and wanted to let ya know I’m hoping you make it. (I said this feeling my words were terribly inadequate, but knowing GQ would know what I was trying to convey.)

GQ: I’m not dddoing good at all. My head is all fffucked up.

Me: Do you know what’s fucking with you?

GQ: Yeah, and I dddon’t wanna talk about it. I’m getting’ my ssshit packed. When do tha property offica usually come?

Me: The last couple of executions she came about six.

GQ: I’ll holla’ at ya after ssshe comes.

Before it was quite 6:00AM, Moriarity, the property officer, came strolling onto the Death Watch section with her inmate helper (trusty), wearing his tailored, bright white State clothing and pushing a heavy, flat wooden cart.

Moriarity: Here’s some chain bags, Jones. (She then pushed several red plastic mesh bags through the side of his cell door.) Separate what you want to take with you to Huntsville and what you want to leave here. (She finished matter-of-factly, as her trusty stood behind her looking like he’d rather be anywhere than participating, even remotely, in the process leading to another inmates’ execution.)

GQ quickly separated his property and was taken to the shower by the two guards working the wing. While he bathed, Moriarity and her trusty went into GQ’s cell and quickly loaded up his property and carted it off. When GQ returned to his cell he called me.

GQ: Billy?

Me: Yeah?

GQ: Iii’m going to go to a visit for about an hour, and ttthen come back here and kick it in the dayroom uuuntil it’s time to tttake that rrride to Huntsville. I’m gonna chill until my visit. Holla at ya later.

Me: WAIT! I gotta tell you something important!

GQ: What?

Me: Make sure you go ‘boom boom’ before you go to visit.

GQ: (Laughing.) Ssshut up, Billy!

I wasn’t too surprise that he’d decided to go to a visit for one hour, but I was wondering if he’d hold to that once he got to the visit. I figured the love he’d feel would hold him there until it was time to be transported to the Death House in Huntsville. But, sure enough, he came back to our dayroom, for about an hour, looking emotionally spent. He hung out with us saying goodbyes and trying to stay composed. All too soon, at just before noon, a lieutenant and a sergeant, in their newest uniforms, came to take GQ away. They tried to be calm and casual as they had him go through the strip search routine, but GQ was indifferent to them. He quickly dressed, turned his back to the hard metal dayroom door, squatted down and placed both arms behind him, out of the waist high slot in the door. The lieutenant quickly placed shiny handcuffs on his slim wrists. As soon as GQ stood up, the picket officer who was watching pressed a button to unlock the dayroom door causing the bolt to snap back like a pistol shot. That abrasive eruption unlocked more than the dayroom. It unlocked the reality we’d all been avoiding for the past hour. Suddenly, we were all aware of where our friend was going. Simultaneously, we erupted with shouted support to GQ. We all knew he walked away from us with our love trailing his every step.

Day of execution: 5:00PM

“Sergeant on the pod,” I heard someone yell out. Knowing that meant rank was about to feed me dinner, I walked to my cell door. Sure enough, Sergeant Schwarz was heading to my door carrying my dinner tray in his giant hand. My tray of food looked minuscule next to his almost-seven-foot-tall body.

“You want anything to drink, Tracy?” He rumbled, in a voice befitting his enormous stature.

“Nah, I don’t want the tray either. Just tell me how Jones was when he left,” I said.

“Well, he handled things pretty good until we put the shackles on him, right before he’d go into the van, then he broke down.” He rumbled again, but with compassion in his voice that you might not expect from a stern looking giant.

That, or something like it, was what I’d been afraid of, and why I’d been so compelled to inquire about GQ’s departure. The thought of him crying in front of his captors, and traveling to his end while so distraught tore at my heart.

Day of execution: 6:30PM

A young female guard was on the Death Watch section crying as she talked to Rambo about how upset she was to lose GQ. Tears stained her unlined face as she mourned someone she’d been trained to feel nothing for.

Neither Rambo, nor I, had ever witnessed a guard cry over one of our deaths. That GQ had so touched this guard says everything about who GQ had become.

“People will not care how you feel until they feel that you care.”

That’s who he was.

Rest in ‘supa dupa’ peace, Mr. Boom Boom.

Always,

Billy

“Execution Politics“

While listening to the “Execution Watch” show on 90.1KPFT the day of my friend Quintin Jones’ execution, I heard it reported at that moment the execution was temporarily put on hold so that Quintin’s lawyers could have an in-person meeting with Texas Governor Greg Abbott to plead for a reprieve for their client.

I am generally very cynical about the intentions of politicians, so I felt instinctively, all the while hoping I was wrong, that Governor Abbott was simply playing politics. As I sat in my cell on Texas’ Death Row, next to the cell Quintin had been removed from just hours earlier, my mind spun trying to ascertain if Quintin had a real chance – or if he was caught in a politician’s machinations.

By that point, the Governor had all the information about Quintin Jones that he needed to make a decision without Quintin’s lawyers repeating what he already knew.

It seemed, after my reflection (and certainly after Quintin’s execution), like the Governor was attempting to make it appear to his critics that he went over and beyond the call of duty to give Quintin a fair chance when he had zero intention of granting him any relief. The astute politician in Governor Abbott would have been well aware of the potentially politically deadly quandary he was in and how his decision in this life or death situation could be used to harm him politically.

In 2018, Governor Abbott gave Thomas Whitaker, who’s white and from a wealthy family, clemency on the day of his scheduled execution, after Thomas’ father, the lone survivor of Thomas’ crime, valiantly pleaded for his son’s life.

Quintin Jones was a poor, black man, from a poor, black family, who, like Thomas, was responsible for killing a family member. And, like Thomas’ father begged the Governor for his son’s life, Quintin’s 90-plus year old great aunt, sister of his victim, begged Governor Abbott to spare the life of the nephew she dearly loved and had wholeheartedly forgiven. Like Mr. Whitaker stated in his plea for his son’s life, Quintin’s great aunt repeated – to kill her loved one was to cause her to go through the pain and grief all over again… to be hurt twice.

Like Thomas, Quintin had spent his years (20) on Death Row evolving into a better person. And, like Thomas, Quintin had never committed a single aggressive act during his confinement… i.e. he’d proven that he was no longer a “future danger” to society.

If Thomas was rehabilitated and redeemed enough to receive clemency, then surely based on the almost identical similarities, Quintin fit the criteria for, at least, a 30-day reprieve.

Governor Abbott knew to deny Quintin any relief would open him up to legitimate criticism about racial and class biases. His last minute meeting with Quintin’s lawyers – a meeting that easily could have occurred at any point over the six months leading up to Quintin’s execution, but would not have carried the same political impact if held then – was Governor Abbott, the politician, putting on a “show” to mitigate the flak he anticipated receiving when he’d ultimately deny Quintin any relief. A show meant to create an illusion that he would consider giving the poor, black Quintin relief as he did the white and privileged Thomas Whitaker. An illusion to cover up his class and racial biases.

What Governor Abbott’s political gamesmanship did was prolong Quintin’s anxiety and stress as he waited long after his appointed 6:00PM execution for the Governor to reject any relief. Quintin sat alone in a bare concrete cell patiently, hopefully, awaiting a rich, white man’s decision if he was worthy to continue in this world.

He waited while “his” Governor played politics.

He waited, hopefully, in vain. And Quintin’s poor great aunt mourns.

John Hummel (Executed: June 30th, 2021)

“Look out, Rambo,” I said, one cold winter morning, as I spoke to John Ramirez who lived two cells away from me on Texas’ Death Row.

“Have you ever heard of a country song called ‘Big Bad John’?”

Before Rambo could answer, I heard the cell door on my left shake and rattle loudly as John Hummel leaned his heavy body onto it. “Did somebody call me?” he asked.

Laughing, I said, “I’ll be damned, you do have a personality.”

That was the first time John and I had ever spoken to each other. It was also the first glimmer I had of his quick wit and amusing nature. With that unexpected one-liner, he disappeared back into his concrete cave, but not before cementing himself forever in my mind as “Big Bad John.”

By that point, he’d been on the Death Watch section with me two separate times for around twelve months total. In that span, he’d emerged from his bunker to recreate twice and go to the shower maybe thrice. He almost never spoke to anyone, but on the rare occasions he did, he revealed little more than a deep-voiced, Southern drawl spoken in a slow, rolling cadence that made you feel Big Bad John was a calm, easygoing person. For someone hoping for the chance to catch a glimpse of his passions, hopes, dreams and sense of humor, his introverted nature was more than a little disappointing.

Big Bad John lived just inches from me, only separated by a thick concrete wall, yet I almost never saw or heard him. I cannot tell you how many times I wondered who he was, what had lead him down a dark path that ended on Death Row, or how he was handling his potential execution and how he had changed since his arrest. But I decided I wouldn’t impose myself on him simply to assuage my endless curiosity. If something occurred naturally that caused us to get to know each other, great. Nothing ever did.

When Big Bad John was returned to Death Watch with his second date of execution, he stated to someone that he had no appealable issues of merit left and fully expected to die on June 30th. From this statement and his reluctance to engage anyone in a conversation, my instinct was that, more than just being an introvert, he didn’t have the energy or desire to get to know anyone and risk caring about them when he felt his death was imminent. We all know that hopeful, joyous feeling when we first make a new friend… imagine feeling that happiness while expecting to die. You would be mourning someone as you grew to know them. I have dealt with a version of this, but being the one left alive – so I know the signs. Being permanently housed on a section with men living out their last moments of life has honed my instincts for knowing when people need, or want, human contact, emotional support – or simply a distraction.

When men arrive on Death Watch with the belief that their time on earth is up, their reactions can be drastically different. Some become manic with the need to experience every last bit of life they can possibly scratch out from the confines of their tiny cells: sleeping as little as possible, talking incessantly to everyone around them, and trying to accomplish any previously neglected goals like writing books, songs, poems, letters or creating various works of art. Some find God and become fanatical with their new found faith, able to talk of little else. And some, like Big Bad John, remain calm and steady while not seeking, or wanting, outside attachments.

The only intrusion I made into Big Bad John’s life was done without any verbal communication. When a mailroom employee delivered a stack of books to him, I was able to read the titles and authors of the books and ascertain that he liked fantasy and science fiction. After that, whenever I finished reading either genre of novel, I’d kick them in front of his cell door when I went to recreation or to the shower for him to retrieve. No words were ever exchanged during this process. I’d make sure to kick the books hard into his steel door so he’d know something was there. When I returned to my cell the books would be gone. For reasons I do not fully understand, this unspoken act left me feeling as though Big Bad John and I had come to a silent understanding with one another. It felt like I was saying, “Hey, I know what you need (books) and don’t need (to be burdened with potentially caring for someone else)”, and his silence was his thanks – not just for the novels, but for my empathy.

As Big Bad John was in the process of being executed by the State of Texas, a 20-minute interview he gave to 90.1KPFT was aired on their “Execution Watch” radio show. In this short interview, he spoke infinitely more words than in the entire year-plus that he lived inches away. As he was being put to death, I learned most of the things about him that I’d been curious about. He grew up lower middle class in the South, joined the Army and due to a high IQ was put in the Intelligence Division. After he was honorably discharged, he moved to Texas and worked various low-level jobs until a terrible back injury left him bedridden for a year. Then, as he began to heal from that, Crohn’s disease struck – once again leaving him bedridden and unable to work or care for himself. He expressed sincere remorse for his crime and didn’t shift blame for his actions onto his recent struggles. He shared his belief in God and how that belief had carried him through his guilt and time on Death Row.

Listening to him speak as I knew he was being poisoned to death was more disconcerting than I can articulate. I was finally coming to know about him as he was dying. It left me feeling hollowed out inside and as if my universe was inverted. In what world is it normal to only know basic things about someone you lived so close to for so long as their existence came to an end?

As I lay in my bed that night, ruminating on my interactions with Big Bad John, a memory resurfaced that made me laugh and feel comforted.

“Brass Monkey” by the Beastie Boys came on the radio and Big Bad John started blaring out the lyrics: “Brass Monkey, chunky, the funky Monkey…”

This was right when the Death Row Warden was standing at my cell door talking to me. A middle-aged, black warden. His dark, expressive eyes went wide when he heard Big Bad John, just a few feet away, yell out “funky Monkey” in a Southern drawl. I quickly told the Warden Big Bad John was singing Beastie Boys’ lyrics and not shouting racial slurs.

I wish circumstances would have been different to allow me the chance to get to know Big Bad John on a personal level. The random glimpses of his personality revealed someone with wit, interesting taste in music, and someone of many layers.

May you rest in peace.

Always,

Billy

Rick Rhoades (Executed: September 28th, 2021)

“Look out, Billy.” I heard called lightly from the cage next to mine as I was listening to my good friend Liliane, a retired molecular biologist, explain how the body processes sugar.

I was sitting on a flat, round, stainless steel stool sunk into the foundation of Texas’ most infamous prison – Polunsky Unit – where Death Row is housed. The unforgivingly hard stool was inside a locked cage in the visitation room where I was having a non-contact visit. It was so cold in the room I was trying not to shiver as I held a solid black plastic phone up to my ear and peered happily through an inch thick sheet of glass at my friend as she animatedly explained the biology of how the human body processes sugar.

Liliane noticed immediately my head cock to the side as I heard my name called and politely stopped speaking. I smiled an apology at her as I turned my head towards the thick wire mesh cage door two inches behind my back and answered “Yeah?”

“Hey, dude. This is Rick. Just wanted to introduce myself.”

“Rick Rhoades?” I asked.

“Yeah,” he replied.

“I’ve heard of you… I heard I gotta watch my woman around you.” I said with a smile in my voice.

From down the long row of visitation cages, someone eavesdropping laughed and interjected. “He’s definitely heard about you, Rick.”

Rick and I both laughed, and just that fast we had an understanding of each other. We briefly chitchatted before I let him know my visitor was still there and I needed to go.

That was my first interaction with Rick. It was over two years later before we had another chance to speak to each other. That was when he received his execution date and was moved to the Death Watch section where I am perpetually housed.

“What’s up, Rick?” I called from inside my concrete cell located in front of the dayroom that Rick had just been put inside.

As he squatted down a little to put his hands, which were handcuffed behind his back, out of a waist high slot in the dayroom door, he turned his head in my direction showing his gleaming bald head, trimmed goatee and handsome face. “Hey, Billy. What’s up?” he said in his soft, almost grouchy voice as the grey clad officer removed the handcuffs.

Rick stood fully erect once the restraints were removed and briefly rubbed his slender pale wrists before grabbing his shirt off of his shoulder and putting the sleeveless, all white shirt over his slightly portly, slightly hairy torso.

“Dina (our mutual friend) told me a good friend of hers was about to get a date and come over here. I figured she was talking about you. When is your date?” I asked in my usually direct manner.

“September 28th,” he answered with a shrug, as if it mattered not a whit.

“Think you’ll make it?” I asked as kindly as is possible to ask such a question.

“No, I don’t,” he stated, just like you say the room is cold. Just stating a fact. Stoicism is the norm for men who have been on Death Row for decades like Rick had by then. Maybe eventually everyone who lives on the Row long enough develops the mental callouses needed to talk about their “chemically encouraged” death so casually.

“You’re still trying to fight this, right?” I asked.

“Of course, but I’m burnt out on living in this little cell. Been on Death Row since 1992, and been in solitary confinement since 1999. If they get me they get me, at least I’ll be out of this place. I only hate leaving behind those who love me and those I love. For them, I’d never give up… but, for me, I’m ready.”

Here, he paused thinking, and then said, “If I could be in general population (not in solitary confinement), or have (he put an imaginary cell phone to his ear), I would feel differently. This (he held his arms out beside his body, pointing at the walls at solitary) is not living.”

“Yeah… I know, but…” I trailed off and we looked at each other knowing that there wasn’t really a way to express the frustration we both felt, but at least finding comfort in the other’s understanding.

A month or so later, Rick was again in the dayroom wearing the same white tank top, showing off his skinny pale arms.

“Rick, since I’ve been on the Row, when your name comes up all I ever hear about is all of these female guards you’ve had fall in love with you bringing you cell phones and drugs, and even more than that about how you and a guy called BD are best friends. Of all of those stories, what interests me most is about BD. Who is he?”

“That’s my best friend, Brian Davis, we’ve known each other 30 years. We were in Harris County Jail raisin’ nine kinds of hell together waiting on our death penalty trials and then to come to the Row. His mom is like my own mom and visits me. Me and BD were even cellies back on Ellis before Death Row was moved here in 1999. He’s a real neat freak and would arrange my stuff the way he wanted it. So, I’d wait until he was gone somewhere and rearrange his stuff a little bit and it drove him nuts,” he said, laughing to himself with a far off look on his face remembering his friend. A look so boyish and full of love, that it was etched forever in my heart and mind. That wonderful look made me instantly feel better inside just knowing and seeing the power of true friendship.

It wasn’t what Rick said that made me realize how much he loved BD, it was that look on his face that made me feel the love he had for BD. This was the first of two occasions when an unguarded look on his remarkably youthful 58-year-old face literally glowed with love for another person. Those two glimpses into Rick’s heart showed me how powerfully he could love another, and made me not only like Rick, but trust him.

Continuing, Rick said, “For years, even over here on Polunsky, we were on the same section together. We’ve got the kind of bond that well…” he trailed off again and looked at me and shrugged his shoulders as if to say, Man, I can’t explain it.

Not knowing that he’d already explained how he felt to me without verbalizing it, I said, probably lamely from his perspective, “I’m pretty sure I get it.”

As I said that, I was thinking about not just knowing someone for 30 years, but having been friends through death penalty trials and decades together on Death Row, where every day is a struggle to survive physically and emotionally. To endure. How many times did those two men lean on each other? How many times did they loan each other the strength to carry on just one more day? How many times were they there for each other when no other inmate was within miles – even though there were always inmates within feet of both of them? How often was their bond tested over three decades and still held strong? Just how powerful was it to simply know, in this dark place, they were never alone? Imagine having that type of a friendship on Death Row.

A few days after Rick’s execution, a Polunsky field minister nicknamed Troop came by my cell to chitchat. Field ministers are inmates who complete a grueling four-year seminary – a Bible College – earning a bachelor’s degree in the process. These inmates are assigned to prisons across Texas, and Troop is one of the two field ministers assigned to walk the runs on the Row, ministering to and just befriending those he can.

“Hey, Troop. Before you get out of here today, swing by and check on BD and see how he’s doing,” I said.

“I’m one step ahead of you, bro,” he replied in his slightly gravely and twangy voice as he peered at me with his intense dark eyes. “I just came from his cell. He was asleep. He’s been sleeping for two days. I’ve been checking on him since Rick died.” As he spoke, his lightly worn and wrinkled face showed concern and compassion.

He continued, “Since I started working Death Row a few months ago, I’ve heard repeatedly about the friendship between BD and Rick. One guy told me that to see them interact with each other – to see their bond – was a beautiful thing. A friendship like that is something.”

“I’ve heard about it too, but not put quite that eloquently. I’m glad you’ve been checking on BD. I don’t know the guy at all, I was just worried about him…” I said, trailing off a bit. “I don’t know, I just think that Rick would want us to check on his friend since he can’t do it anymore,” I said.

“I’ll make sure to check on him pretty regularly,” Troop said, and I knew he would.

You can rest in peace, Rick. A lot of people are looking out for your friend.

“And in the end, the love you take is equal to the love you make.”

– Paul McCartney

Always,

Billy

Note from Dina: Rick was a close friend to me, so I travelled to Texas to be with him at his final visits and witnessed his execution. Billy and I visited a few days afterwards and agreed that we should each write our own farewells for him. When we shared them with each other, we were struck by how similar our feelings about Rick ended up being: a testament to the man he was. At Billy’s request, my farewell to Rick has been included.

A Farewell to Rick Rhoades (Executed: September 28th, 2021)

By Dina Milito

“I’m a fuck up,” Rick said. We sat across from one another, talking through a phone, close but unable to touch because of the glass separating us. I told him I didn’t see him that way.

I was introduced to Rick in the visiting room at Polunsky, but had seen him many times before that day, when our visits with other people overlapped. So when we began writing, it was with the familiarity of shared space and friends in common. He had been on Death Row long enough to remember being housed at Ellis Unit, the old Death Row. He had done time with one of my favorite prison writers, James Beathard, who was executed long before I discovered his work, and patiently answered my many questions about him. He had spent more than half his life in prison and was generous in sharing his reflections on it. “It sucks. I hate it here,” he told me many times. And yet, over the years I knew him, it became as clear as the glass between us that he had carved out a meaningful life for himself. Despite a tragic trajectory, Rick’s life was populated by people he loved, who loved him back.

BD was Rick’s best friend, brother, and closest ally. They arrived on Death Row within a few months of each other and had been friends and sometimes cellies from the start. Rick trusted and loved BD like no one else, and their humor (often at one another’s expense) and deep friendship was recognized by all who spent time around them. Rick considered BD’s family, especially Joyce and Tim, to be his own. Joyce and Tim visited Rick and BD regularly for decades, and sent books (Rick was an avid reader), and their love and friendship meant the world to him. He loved Tim’s raccoon stories and knew he could count on Joyce for anything. During his final hours, Rick repeatedly expressed love and concern for BD. BD, I vowed to Rick that I’d regularly remind you that you made him a promise and he wants you to honor it, and that he loved you and you were his brother.

Rick had a loving and playful relationship with his own mother. Sometimes he’d ask me to call her and relay messages. The very first message was to wish her a happy birthday, and to ask her why she looked so old, when he looked so young. I expressed reservations, but he insisted. On the phone, she laughed (thank goodness!) and said she wouldn’t have believed any message was from Rick if it didn’t contain a smart-alecky remark. She told me what a sweet and loving son he had been, how he shared a special bond with his father, and how very much she loved him and loved being his mother.

In addition to family, Rick built close friendships with people in the freeworld who reached out to him, and he had several close longtime friends who supported him through letters and who came to feel like extended family to him. (To be respectful of privacy, I won’t mention names, but you know who you are and that Rick loved you. I know it too!) And no description of Rick’s relationships would be complete without mentioning his friends on Death Row. Since Rick’s execution, I have received letters sharing memories, grieving his death, asking for photos as mementos, and writing about how much he was going to be missed. Several of the prison staff also expressed to me sorrow over Rick’s execution date. He left an impression on so many who knew him.

During Rick’s final visits, he talked extensively about the people he cared for, the memories he cherished, and the regrets he harbored. He spoke of the daughter of his victim, born after her father’s death, and his sorrow for the pain he had caused her family. He discussed the hurt his own family suffered because of his actions. He never forgave himself for the damage he caused. As a result, he accepted his fate as it was, sharing that he felt he was a fuck up as we sat together in the visiting booth. The news articles written on Rick’s case described him as irredeemable. So many of us with flaws wish for redemption and love despite them. When pondering the many good people in Rick’s corner, I wonder if perhaps he attained more than he gave himself credit for. Death Row is a cold place, but Rick managed to create a warm circle of love and support, suggesting that there was more to who he was than his regrettable mistakes the media reported on. And if we choose to measure a life well-lived by how much love we exit with, then perhaps Rick wasn’t such a fuck up after all.

I miss you, Old Man! I hope the fish are biting!

Life Watch Update: October 25th, 2021

It has been awhile since my last posting. That is a good thing. It means Texas has its blood thirsty maw strapped shut and few of our friends are being chewed up by the Texas Death Machine.

For those not too familiar with the glut of recent non-COVID-19-related stays of execution given out, here’s a brief explanation of what has been going on. Just try not to let the length that Texas has gone to obstruct the Supreme Court and religious rights piss you off too much.

The Supreme Court granted a stay to Texas Death Row inmate Patrick Murphy on November 13th, 2019, the day of his execution, because Murphy, a Buddhist, had requested a monk be allowed in the Death Chamber with him. At that time, the Texas Department of Criminal justice (TDCJ) only allowed their own Christian chaplain to be present in the Death Chamber. The Supreme Court determined this practice was discriminatory.

TDCJ then instituted a new policy: Inmates would no longer be allowed a spiritual advisor of any religion at the Death Chamber with them.

On June 16th, 2020, the day Ruben Gutierrez was scheduled to be executed, the Supreme Court stayed his execution, ruling he was entitled to a spiritual advisor in the Death Chamber with him. TDCJ then changed its policy – AGAIN – allowing an inmate of any faith to have a spiritual advisor in the Death Chamber with them, so long as the inmate and spiritual advisor complied with a few reasonable rules prior to the inmate’s execution.

However, TDCJ decided it was a “threat to security” to allow the spiritual advisor to touch the condemned or pray aloud with them in the Death Chamber. The spiritual advisor had to stand silently in the corner and be a mere observer. A violation of either edict would result in immediate physical removal of the spiritual advisor by an extraction team on standby waiting outside.

The executions of Quintin Jones and John Hummel were carried out under those new protocols.

After John Hummel’s execution, his spiritual advisor was contacted by condemned inmate John Ramirez’s attorneys. At their request, he wrote an affidavit chronicling the execution process and not being allowed to touch or pray with John Hummel. It was then discovered, through a book written by TDCJ’s own chaplain, that prior to TDCJ stopping the spiritual advisor from touching and praying with the condemned in the Death Chamber, that not only was it not a “threat to security” for the chaplain to touch and pray with the inmate, but it was part of the State’s “Execution Protocol” for the chaplain to touch the inmate’s foot and pray. When the chaplain ended his prayer and went silent, that was the executioner’s cue to release the poison into the strapped down inmate’s veins.

On September 8th, 2021, the day of John Ramirez’s execution, the Supreme Court granted him a stay and set a hearing for oral arguments to sort out the religious rights of condemned men. Mr. Ramirez’s attorneys had appealed to the nation’s highest court to protect his religious rights and exposed TDCJ’s machinations of manufacturing a “threat to security” issue as an excuse to disallow spiritual advisors from praying with and touching the condemned inmate. Oral arguments before the Supreme Court are set for early-November 2021, and the ruling is expected to be released in the summer of 2022. No executions are expected to take place until this ruling is made.

Now that the technical news is out of the way, here is the main update:

Since Hurricane COVID hit our shores in 2020, there have been twenty stays granted (counting those stays issued for non-COVID reasons). The ceasefire has done wonders for the morale on Death Row, especially for those receiving execution dates and being moved to the Death Watch section.

In early-2020, everyone pretty much knew, due to Hurricane COVID, they wouldn’t be executed. Then, once the storms generated by the foul winds of COVID-19 abated, and the anxiety levels of the men on Death Row began to rise again, like a savior, the religious rights issue reared its almighty head, causing the Supreme Court Justices to take a Texas-sized bite out of some Texas ass. Now, Death Row is back in calm waters – for now.

The lessened tension is palpable. I’ve been told, often, by men days from death that they felt no stress or tension. At the time of their stoic denial, they did not know they were lying. It wasn’t until they received a stay of execution, and felt their mind and body relax, that they understood just how tightly they’d been wound. It wasn’t until then they could breathe deeply.

Now, imagine the bulk of the men on Death Row being able to relax in one long, slowly released collective breath. Now, imagine how enjoyable that must feel for men who’ve spent years, even multiple decades, holding that tension in: pretty good.

Always,

Billy

No Comments