“Hunter,” the counselor called to me as I was packing to leave the Covid housing unit, my ten-day quarantine complete. “Your Annual Review is next week.”

“I’ll just sign off.”

“We’re putting you up for transfer.”

This caught my attention: I stopped stacking my belongings onto a cart and turned towards her.

“I told the sergeants and lieutenants I’d stay as Captain’s clerk until November, can’t we just kick this back ’til next year?”

“We can get Captain’s clerks anywhere,” she said curtly. “You’ve been a medium-security prisoner since 2018, four years now; we need to move you out of maximum security.”

A year ago, I’d been perfectly happy working as the Law Library clerk when Sergeant Clark asked me to return to the custody office as the Captain’s clerk. I told him I’d been there, done that, got the t-shirt and started to walk away, but then a thought hit me. I turned back, and asked, “If I come back and work for you, would you be willing to help me out if I have a problem with my housing?”

“I’ve known you for fifteen years,” the sergeant answered lazily, “you can get at me whether you come back to work for me or not.”

I took the job, my third time working in the custody office. Now the counselor is saying they can replace me easily. I felt a bit offended.

“I’m putting you up for Ironwood prison.”

“That’s way out by the Arizona border. I’m not eligible.” “Yes, you are,” she said, biting the words off grimly.

“Okay,” I shrugged.

Studying me for a moment, she whirled away, returned a minute later, and said, “You’re right. You’re not eligible for there. I’m putting you up for Soledad.”

Soledad would be fine. Paul, my cellmate at Jamestown, was there, but I wasn’t eligible for Soledad either.

I nodded and signed off my right to attend the Classification hearing. The only reason to go was to talk to the Captain, but he was my supervisor, and I’d be talking to him as soon as I moved my belongings out of the quarantine unit and returned to work.

“Can’t you talk to Associate Warden Martin?” I asked the captain the next day. “Every year he asks me if I want to remain here. I say yes, and he pulls my transfer.”

“Martin retired.” “Oh.”

The counselor dropped by my office. “Hunter, you’re not eligible for Soledad.” I nodded.

“You knew that already?” I shrugged.

“Why didn’t you tell me?”

“You seemed upset when I told you Ironwood was a no-go.”

“How else am I going to learn?”

Training her wasn’t my problem, although she seemed to be a problem. “You can go to Pelican Bay or Corcoran. Do you have a preference?”

Both prisons had terrible reputations, but Pelican Bay was all the way up by the Oregon border and Corcoran was only about forty minutes away. I picked Corcoran.

A few weeks later, I took all my property to R&R. I was allowed three boxes, which seemed rather sparse after four decades in custody. The guard was fine, he inventoried my belongings and I returned to my facility.

Walking into my cell, I spotted my fan under my bunk. Damn! I forgot to pack it. I went to work and told Sergeant Clark about my fan.

“Here’s one,” he reached into a locker.

“I have a fan, it’s in my cell and I need it in my property at R&R awaiting the bus.” “Nothing I can do for you there.”

“I know.”

Sergeant Clark bid me good luck, and we shook hands.

I sold my fan for some junk food. While munching empty calories, listening to a borrowed radio in my cell, I was called to Medical for a Covid test.

“I don’t want to test.”

“If you don’t, you’ll go straight to quarantine when you get to Corcoran.” I tested and was negative.

Next morning at 5:00am I went to R&R where I was tested yet again for Covid with another negative result, and I finally pulled on a red paper jumpsuit and boarded the bus for Corcoran.

An hour later I looked intently out the window of the bus and saw my three boxes of property go into Corcoran’s R&R and sighed with relief. Pulled from the bus, I was tossed and lost inside a holding tank. A sign on the wall said, “No Property issued inside R&R.”

When I went for my photo, I asked the female guard, “I won’t receive property here?”

“No, you’re going to facility 38. I send property there on Tuesdays.” “Today is Tuesday,” I said hopefully.

“Next Tuesday.” “Oh.”

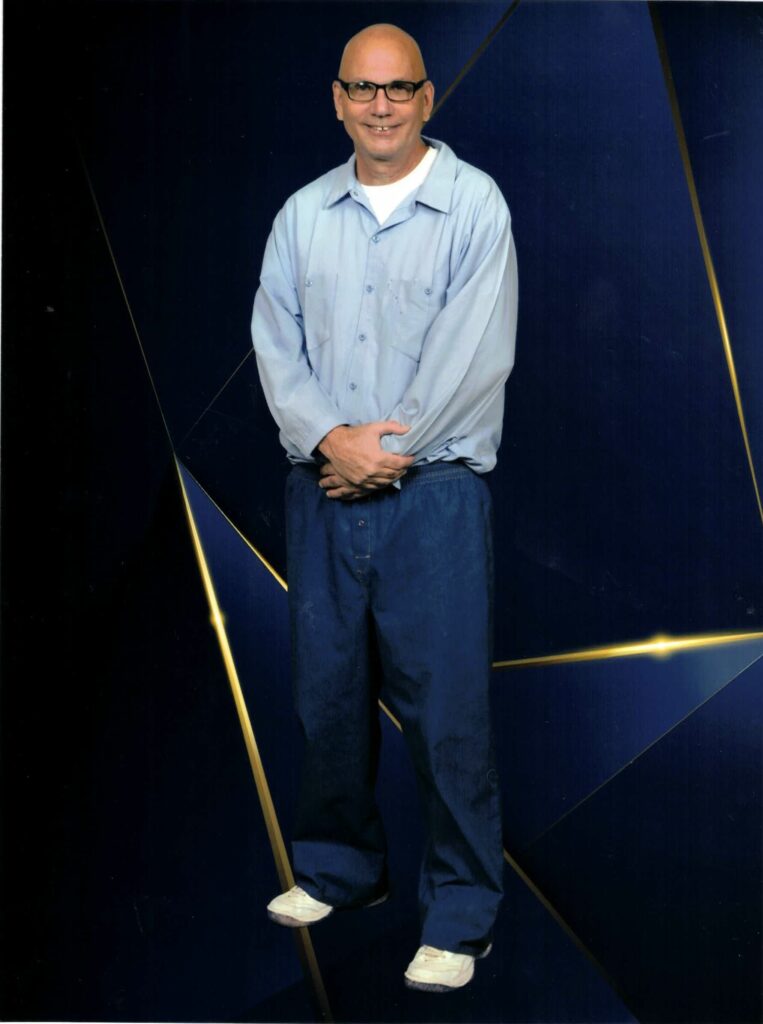

“Hunter,” a guard called me out of the holding tank a couple hours later. Handing me a fish kit containing a roll of toilet paper, a bar of soap, one bed sheet, one blanket, blue pants and a blue shirt, I was marched off in handcuffs to my medium security facility.

The yard had lush grass, a couple of run tracks, a softball field, soccer field, workout areas with pull-up and dips bars, but the thing I noticed the most was how many old guys were on the facility. I had been just about the oldest guy at the maximum-security yard, but here there were wheelchairs, walkers, men carrying canes, all wearing green mobility-impaired vests. I also noted there didn’t seem to be any tension, prisoners were not grouping by race, no one seemed to be hyper-vigilant, the atmosphere was relaxed, almost cheerful, quite alien to my experience.

The guard escorted me into a housing unit, and I immediately saw the PPE station—I was back on quarantine! I had tested negative twice, but I was stuck in quarantine again. There were one hundred cells in the housing unit, each cell had two bunks, but we only had three prisoners housed there. Each morning after they collected my breakfast tray, they’d let me out for a shower and phone call and then back in the cell until the next day. I resolved to refuse to let medical staff take my vitals or cooperate in any way until they explained to me why I was in quarantine. My master plan was thwarted when medical staff didn’t come to see me even one time.

The following Tuesday, I stood by my cell door awaiting my property the guard in R&R had said would be sent that day. No luck. I asked a housing unit guard when I might receive my property and he said the officer generally handed it out on Wednesdays.

The next day I didn’t receive anything either. I was getting really tired of living out of a fish kit, I really wanted some hygiene items, personal clothing and of course my TV and radio.

I phoned a friend, and she called Corcoran and spoke with a sergeant who promised he’d come talk to me and said I’d receive my belongings right away. Nothing happened. When I phoned again, she told me the staff seemed very friendly and willing to help me, but I didn’t receive my property, nor did anyone communicate with me. The experience was like punching marshmallows.

I went to Classification, the Captain said he didn’t know why I was on quarantine or when I’d get off, he added that I should receive my property soon. I remained on quarantine and did not receive my property or hear anything about it from anyone.

After two weeks, I’d had enough and on a phone call I semi-raged that I was going to assert safety concerns and just get off the facility. I was counseled to stay calm, and I felt better after letting out my frustration.

The housing unit officers stopped me on the way back to my cell, and they said they had been monitoring my phone calls and asked about my concerns. When I told them I’d been placed on quarantine for an unknown reason and hadn’t received my belongings, they said they could not address the medical situation, but they’d find out about my property. The next day they told me they had spoken to the property officer, and I’d receive my property on Monday, thirteen days after my Corcoran arrival. Midmorning, the property officer rolled in a cart and delivered my belongings. I happily changed into my personal clothes, set up my TV, radio, and placed books on my shelf.

Another week went by before I was released from quarantine, but truthfully now that I had hygiene items, personal food, coffee, appliances, entertainment devices, I didn’t really care that much anymore.

I placed my property on a cart and wheeled it to the housing unit next door. When I got to my cell, the lone occupant was moving out. While I waited for him, prisoners came by and said, “Welcome to Hotel Hell.” Although the movement seemed random, almost like a college dorm instead of a prisoner dayroom, it didn’t seem too hellish to me. When the cell was vacant, I cleaned it, hooked up lines for my clothing and unpacked my belongings.

When I went out to the dayroom I was surprised that I didn’t know anyone. The prisoners I met were mostly only months out of the reception center doing a year or two and then heading home. This was way outside my previous experience of eighteen years on San Quentin’s Death Row and then a couple more decades of maximum-security prison.

The next morning after breakfast, I went to the yard and ventured into the library. It was the worst one I’ve ever seen. Just a sparse jumble of books on a very few shelves in no particular order. I checked out All Quiet on the Western Front.

Exiting out to the yard, I strolled around and spied a few score of cats padding around just outside the chow hall. They seemed to believe—no doubt correctly—that they were Gods and we were minions placed on earth to serve them. The cats recognized the prisoners who brought them food daily and would race over and loudly demand their tithe.

Some prisoners started carrying a drum set, guitars, amps, speakers out of the gym and set them up on the yard. Four prisoners tuned up and started playing alternative rock, adding a stellar soundtrack to the festivities.

Living in medium security with prisoners coming and going all the time is unsettling to me after being warehoused in facilities where no one was going anywhere except to the execution chamber or insane. I’m not sure if this is the place for me or I’m the person for this place, but I suspect we both have something we can learn from each other.

-The End-

No Comments