Twelve hundred beds needed to be filled at the United States Penitentiary in Lewisburg, Pennsylvania. That was the problem prison officials faced when they decided to turn Lewisburg into a lockdown program called the Special Management Unit (SMU). How they decided to solve their problem was just as sinister as the SMU itself.

Prisoners were rounded-up off penitentiary compounds and arbitrarily labeled as management problems to justify their placement in the SMU. Prisoners who had been keeping clear conduct for years found themselves in front of the hearing officer explaining why they shouldn’t be sent to the program.

After spending about eight years in the highest security prison in America, the Administrative Maximum (ADX), I was transferred to Allenwood United States Penitentiary in Pennsylvania in September of 2008, which came as a relief after the harsh and psychologically harmful environment of the ADX; where inmates like Ramsey Yousef, the first World Trade Center bomber, and Eric Rudolph, the Olympic Park Bomber are housed.

Not long after I arrived at Allenwood, a rumor circulated around the penitentiary of a list with the names of prisoners who were supposed to be taken off the compound for placement at the new SMU program at Lewisburg. To some it sounded too conspiratorial to be believed; others weren’t concerned because they had been maintaining clear conduct. It just couldn’t concern me because I had just been released from the ADX program after serving an excessive amount of time there.

Our apathy was being fed by changes that were supposed to have been taking place in Washington. At the time, many of us believed that the program at Lewisburg, the secret prisons around the world, and Guantanamo Bay-type programs were all products of the Bush Administration. We were convinced that the Obama Administration would never allow a sadistic program like the SMU to be implemented under their watch. But we were all wrong, and naively so. Because while Guantanamo Bay, at the time, was rumored to be in the process of closing, a version of it was being opened here in America at Lewisburg for us. And not for Al Quaeda members; but even though we were not terrorists, we were treated as such.

After about four months on the compound at Allenwood, I was found in possession of a four inch piece of metal that they claimed could have been used as a weapon. As a consequence, I was given 60 days in the Segregation Housing Unit (SHU), along with other sanctions.

Halfway through my SHU time the rumors about the list proved to be true. We began to see prisoners being rounded-up off the compound, and notified of their so-called rights to challenge their SMU referral. We were told that we could present evidence and call witnesses etc. to disprove being labeled a management problem. This made prisoners hopeful. Most, if not all, believed they had a chance to convince the hearing officer they didn’t fit the criteria for placement in the program.

But they were all disappointed. Because they all returned from their hearings with the same outcome: They were all SMU bound.

I was naive enough to be hopeful that I wouldn’t be one of those referred to the SMU. But I was wrong, too. I was served with the same notice and read the same rights as my fellow convicts.

I immediately contested the referral to the counselor notifying me. I told him that I had just been released from the ADX program after doing about eight years there, so another term in the SMU would be excessive and unjust. But my reasoning fell on deaf ears. The counselor responded sarcastically by saying, “Unfortunately for you, they will need to fill the bed spaces at Lewisburg, so your name was placed on the list.”

Before I even received my hearing, I was told to pack my property because I was scheduled to be transferred to the SMU program at Lewisburg. When I reached R&D, seven other prisoners were also waiting to make the same trip. After we were all humiliated by the strip searches, fingerprinting and the usual rituals of defeat, we were all shackled and loaded into a van to be taken to Lewisburg.

The ride from Allenwood to Lewisburg took about thirty minutes. We were received with the same humiliation at Lewisburg that we were sent off with at Allenwood. The usual rituals of defeat were performed. I was given a bed roll and placed in a cell no bigger than an outhouse and just as filthy. G-Unit was turned into the SMU and it was notorious for its rats and roaches.

I opened the window and heard convicts talking to each other through their windows from one unit to the next. They came from all over; from penitentiaries in Louisiana, California, Florida and Virginia. They talked about being shipped far away from their families and friends. Some had already had their hearings, and some hadn’t. Of those who hadn’t, some were still hopeful they may be rejected by the program. Others who knew better said so, to the dismay of the still hopeful ones.

In the morning, I was awakened by the noise coming from the heavy machinery working to put the finishing touches on Lewisburg to make it a ‘Lockdown Program Facility’ for the SMU.

Later that day, a guard told me that my hearing would be held in Lewisburg. I asked him, “Why have a hearing?” Because my transfer to the program before I had a hearing demonstrated it would be nothing but a sham. He agreed, and then he walked away.

Even though they claim that the SMU is a non-punitive program, very few things at the ADX, which is a punitive program, prepared me for the harsh and inhumane conditions of the SMU.

At the ADX prisoners had control over the lights in their cells and could turn them off and on as needed. But here in the SMU prisoners have no control over the light, which is kept on from six in the morning until midnight. At the ADX we were allowed to keep our personal property; but here we are deprived of personal property pending advancement in the program. At the ADX we were allowed to view religious programs on TV; but here we are denied that privilege, one that even detainees at Guantanamo Bay enjoy. At the ADX we were given recreation about twelve hours a week; but here we are only given recreation for five hours a week, which can be arbitrarily denied. At the ADX we had single cells; but here we are forced by gassing, restraints and other torture methods to accept a cellmate whom we may end up fighting.

So, despite the semantics of the Bureau of Prisons (BOP), not only is the program punitive, but it is more detrimental psychologically than I can ever explain here. Suffice it to say that prisoners are being put in four-point restraints for days and left to urinate and defecate on themselves for refusing to accept a cellmate whom they may not be compatible with. As a result, prisoners lives are being jeopardized, as I am about to explain.

The day came for my hearing. I saw prisoners coming out of the hearing area complaining. I was taken to the room in restraints. Before I sat down, before I even said a word or presented my case, the hearing officer told me that I fit the criteria. He recommended that I would be placed in the program. I asked him about due process, and he told me that this was the most due process I could expect.

About two days later, all the prisoners who’d had their hearing were taken to the Z-Unit section of the prison. The cells there were much bigger and cleaner, and had showers. I guess this was a more humane method to impose their injustice.

I was placed alone in a cell. Most of the cells on the unit were empty. But later that night prisoners came from several other penitentiaries. Some were forced into cells with other inmates they didn’t know, nor had anything in common with. This is a dangerous practice that has cost prisoners their lives in the past, and will in the future.

A Brief History of Lewisburg and Me

I stated here that I was transferred from the ADX to USP Allenwood in September of 2008. I should also mention that I was sent to the ADX by prison officials in Lewisburg. I was an inmate at Lewisburg from 1998 to 2000, before it was transformed into a lockdown facility to accommodate the SMU. So, I knew several of the guards, and they knew me. When I was an inmate at Lewisburg, I used to work at the Unicor faculty. I participated in the GED program, where I passed the test and received my GED.

I also used to participate in the religious activities of the Rastafarian community. So, when the penitentiary became flooded with marijuana, the Rastafarian community was immediately suspected to be the culprit. And when the urine analysis tests of prisoners started to come back dirty, unscrupulous prisoners started to point their fingers at the Rastafarian community to escape punishment.

Religious contractors were allowed to visit prisons to preach and worship with prisoners; the Rastafarian community had a regular visitor. So, the prison officials concluded that he must have been the source of the marijuana. One day, he was scheduled to visit the prison to celebrate a Rastafarian holy day with his imprisoned brothers. When he arrived, he parked his car in the prison’s parking lot and started to enter the prison, but he was denied entry. He was searched but no drugs were found on him. However, they searched his car and found a pound of marijuana.

I was then immediately put in restraints and taken to the lieutenant’s office. I declined to talk. I was then taken to G-Unit, which was the SHU. I was placed under investigation, and I was forced into a cell with an inmate who was a suspected informant. They wanted this inmate to spy on me.

So, to counter their plan, I overpowered the suspected spy, taking him down onto the floor of the cell, and stood on his neck. I told him to scream for help. He complied, and when the guard appeared, I demanded to speak to the warden, because the inmate shouldn’t have been in the cell with me. After a back and forth of demands, the guards came with a team of about eight, and stormed the cell. I was then placed in restraints and four-pointed.

I was eventually written up for conspiracy to introduce drugs into the prison and taking a hostage. I was found guilty, and along with numerous sanctions, I was given a disciplinary transfer to the ADX. I was held in the ADX from 2000 until September of 2008, when I was transferred to Allenwood. So it was deja vu to be back in Lewisburg; but this time in the SMU.

Bloodshed instigated!

I was left alone in the cell until another busload of prisoners came about two days later. I was told by a guard to get ready because I would be receiving a cellmate. So, I cleared some of my belongings off the top bunk to accommodate my fellow convict. He was brought to the cell, and I was told to cuff-up. I complied. They opened the door and placed him in the cell with me. They closed the door behind him and he immediately pushed his hands through the tray-slot to be uncuffed first, thus leaving me cuffed-up and vulnerable. But after he was done, I did the same without incident.

The guards left us there in the cell, I introduced myself, but he ignored my attempt to be cordial by demanding that he be given the bottom bunk because he had a medical pass for it. “That’s not gonna happen,” I said. “I have a bullet in my ankle. I don’t have a medical pass, but I don’t need one.”

“It’s like that?” he asked.

“Yes. You need to get into one of these empty cells. And you need to do it now, or just get on the top bunk here,” I answered.

He decided to take my advice. When the guards came back to make their rounds, he requested to be moved immediately because we were not compatible, but the guards ignored him and walked away. He then started to kick the door to get the guards’ attention. When that didn’t work, he started to shout, “C.O., I need to see you.” He did this repeatedly while kicking on the door, but the guards still ignored him.

Other convicts started to kick their doors and yell to get the guards’ attention. This went on for about ten minutes before several guards came to see him. He told them that he needed to move because he needed a bottom bunk, but the guards told him that was not going to happen. Even though I had the bottom bunk, one of them told him, “Get that bunk right there,” pointing to my made up bed. Other inmates heard this and knew what it implied, so they began to kick on their doors again, demanding the guards move him instead of trying to instigate bloodshed.

While all of this was going on I told him it would be best if he would just take the top bunk and try to move when a different shift of guards were working, because it was quite clear what the guards wanted to see: they wanted to see us fight for the bottom bunk and I didn’t want that.

A guard then returned to our cell and told me to get ready to move into another cell with somebody else. I told him I wasn’t going to move, and he walked away. This was done to further inflame the situation, which I explained to my cellmate and he agreed. We decided to try again, when a more reasonable group of staff was working.

However, our other attempts also failed. This made the situation very tense, so I decided to make arrangements to move to another cell with a convict that I was compatible with. Before I was able to make that move though, the situation exploded into violence. Unfortunately for convicts, when it gets to that point, the only winners are the prison officials, as this incident and many others like it demonstrates.

He was well aware of the nefarious plot of the guards. He knew that I was making arrangements to move to another cell; and that if we ended up fighting each other for the bottom bunk we would be playing right into the hands of the instigators. Despite all this, he attacked me.

He struck me with a body blow that almost made me collapse. I remained standing and countered with a blow to his chest that backed him up, but he grabbed my dreads and twisted my head in a way that made it impossible for me to throw any more punches.

A guard stood by the cell door and watched us fighting. But instead of alerting the emergency response team, he walked away and allowed it to continue.

With this harsh reality in mind, I grabbed one of his legs and swept him off his feet. This gave me enough room to connect with a blow to his face. He let my dreads go. I got on top of him and began punching his face until he started to bleed. He said he gave up, so I got off him and told him to get the guard’s attention. He faked and tried to knock me out with a blow to my head but it didn’t work, so the fighting resumed.

He threw his punches, and I threw mine. He kicked, and I kicked. He bled, and I bled. Then I connected with a blow to his head that made him collapse. A stream of blood was flowing from his head. The walls in the cell were splattered with blood. I only had a scratch under my right eye; the blood on the walls and floor wasn’t mine. Blood was still streaming from his head, so I called out for the guards, but they continued to ignore me.

I peeped out of a crack on the side of the door and saw a guard on the range. I called out to him, but he paid me no mind. Other convicts then started to call out to him, but the guard took his time responding. I yelled, “You want to see niggas kill niggas? Well, I’m not gonna be the flunkie in your fucking game!”

He slowly approached the cell door and stared in. I screamed at him, “This is what you wanted, you bitch.” He responded with a smile. His sarcasm infuriated me, so I challenged him. “Open this door and come in here. I bet you, I’ll make you cry,” I said. But the coward just walked away.

My cellie was still on the floor, barely moving with blood surrounding his body. I screamed through the opening on the side of the door, “Man down, man down.”

I saw a group of guards walking slowly towards my cell. The lieutenant came to the cell and stared in, and told me to cuff-up. But I told him that he needed to first cuff-up my cellie. He demanded in an authoritative voice, “I said to cuff-up now.”

“I’m not gonna get in restraints while he’s not. So, let me help him to the door and you can cuff him up first.”

He pointed the gas canister through the tray-slot and said, “If you don’t cuff-up now, I’ll gas you.”

Angrily I said, “Fuck you, you’re not gonna set me up and get me killed while I’m in restraints.”

This is all a deadly practice, especially in these kinds of situations when violence has already been committed. To cuff-up while my cellie remained uncuffed could have been suicidal. He could have been playing possum, waiting for me to cuff-up so he could attack me while I was in restraints. I therefore refused to cuff-up. The lieutenant gassed me with a chemical that got into my eyes and on my skin and burned me intensely. The gas blinded me and felt like it was eating away my skin. The lieutenant saw that it was working, so he demanded in a loud voice, “I said to cuff-up now.”

I responded defiantly, “Fuck you.” So he gassed me again. The burning became even more intense and unbearable. I therefore found my way to the tray-slot and allowed my hands to be cuffed.

My suspicions were immediately realized. As soon as I was in restraints, I was gassed again. Then I heard the lieutenant encouraging my cellie to get up. I couldn’t see, so I was certain that he would attack me while I was in restraints. The lieutenant continued to encourage him, saying “Get up. He’s cuffed-up. Get up!” Implying I was vulnerable to be attacked. Fortunately for me, he was really out.

Later on, I found out that this same lieutenant was involved in a similar incident where two inmates were forced into a cell with each other. A fight broke out between the two, and before it was over, one inmate was dead. So, the lieutenant was well-aware of the dangerous nature of the situation. Nonetheless, he was still instigating violence between prisoners.

I was handcuffed, burning and blinded by the gas, and my cellie lay unconscious on the floor. Yet the lieutenant and other guards refused to enter the cell to try and save him. Instead, the lieutenant engaged in trickery by yelling at my cellie to get up, knowing that he couldn’t. This prolonged the incident. I walked over to the door and shouted so that the other convicts could know what was happening in the cell. “I’m cuffed-up. I got gas in my eyes. I can’t even see and my cellie is not moving. They want him to die, that’s why they’re leaving him in here. They want me to kill him.”

The lieutenant screamed, “Shut up and get away from the door.” He gassed me again.

This time the gas was more intense than before, so I blindly staggered toward the shower. After a brief search, I found it and got in. My hands were cuffed-up behind my back, so I used my forehead to turn it on. I felt like I was on fire, but when the water came pouring down on me, it felt like the fire was extinguished. I let the water continue to cleanse my eyes of the chemicals while the lieutenant was arbitrarily prolonging the incident.

Enough of the chemicals cleared out of my eyes for me to see the gang of guards all standing by the cell door with the lieutenant in front. He was still yelling at my cellie to get up. My cellie started to move, but it looked like he was choking on blood. I began to loudly narrate everything that was happening in the cell. “He needs help. They want him to die. He needs help. He is choking on his blood. He’s too weak to stand up and they know it.” They still didn’t enter the cell to save him.

I began to talk to my cellie, hoping he could hear me. “These bitch ass police want you to die. Try and crawl towards the door, so they can cuff you and take you to the hospital. If not, they’ll let you bleed to death in here.” I kept repeating this part until he started to move and crawl towards the door.

He tried to get up, but couldn’t. He raised one of his hands to the tray-slot. One of the guards placed a handcuff on that hand. His hand then fell along with the cuff, so they screamed at him to lift both hands, so both could be cuffed-up.

They then opened the door and dragged him out and placed him on a stretcher. They stormed the cell, cursing me and calling me a bitch. They slammed me down on the bed and held me there while others were twisting handcuffs to inflict extreme pain to my wrists, and some were hitting me on the back and ribs. They stood me up and walked me out of the cell, down the range, where they pushed me in a small dry cell. I was locked in there and told to burn. I was left in restraints, and even though the water had eased the burning, I still felt like I was on fire.

After being in the dry cell for about an hour, a group of guards came along with a camera to record my strip search. To preserve evidence after the search, I was seen by a paramedic. After the paramedic, an FBI agent was there to see me, but I declined to make a statement. I was then escorted to an empty cell. As my mind started to process everything, I couldn’t help but realize that this was only my first week in the SMU.

The Cellmate Dilemma

Picking or accepting another person to live in a cell with you has the potential of becoming a life or death decision. This is not an exaggeration. To live in a cell that is no bigger than the average bathroom could be extremely stressful, but to live in a cell of that size with another person is not only extremely stressful, but could also be deadly.

The moment you enter a cell with another person, you become vulnerable to that person’s worst instincts. Every inmate has a history, which is most often an unknown factor. In an environment like the SMU, it’s not unusual to find yourself in a cell with a complete stranger. After you’re forced into a cell, and after pleasantries are exchanged with your reluctant cellie, the obvious must then be addressed: Who are you?

That is the question that corners my mind the moment I see or become aware of someone who may become my cellie. I always try to initiate a handshake, make eye contact, introduce myself, and, in my own way, I try to project peace while I scan the face and eyes of my potential cellie for treachery. I would be remiss if I failed to perform these essentials that have now become rituals.

The key to successfully completing the SMU without being killed or killing your cellie is to find a reasonable cellie. I eventually came across a cellie who was reasonable enough to realize that we must find a way to live in such a small and cramped space without trying to kill each other. In the SMU, we are confined to our cells for twenty-three hours a day on weekdays, while on the weekends, we spend the entire forty-eight hours on lockdown. To overcome the stress of being confined like animals in a zoo, we turned our cell into a gym when we exercised, into a school of liberation when we read, studied and reasoned, and into a temple when we worshipped our God Jah Rastafary. My cellie and I were both practicing Rastafarians, but we were not perfect – the harsh conditions that we lived under revealed our imperfections. The times when prisoners are fed are often the most tense times, because around feeding time some inmates jockey to get access to the tray-slot to get the best tray for themselves, while leaving the tray with less food for their cellie. My cellie was no different when it came to food. When we first became cellies, he used to stand guard by the door to assure that he got the best tray for himself. I allowed him to do this shameful act several times, so that it would be well-established to us just what he was doing.

Then one day around feeding time he was standing by the door as expected. I got off my bed and walked over to him. I told him to get out of my way. He hesitated for a second, and then moved. I took my stand by the door. When the guard passed me the food trays, I made sure my cellie got the best tray. My tray was messed up, so I showed it to the guard. He passed me another tray. I tried to return the messed up tray, but the guard told me to keep it. So, I ended up with two trays. But I took the extra tray and shared it with my cellie.

After we were done eating, I noticed he was quiet. I looked at him, but he avoided eye contact. I decided not to say anything. The vibe that I received from him wasn’t malicious; it was obvious that he was embarrassed. Then he spoke with a contrite voice, “I’m sorry for acting that way. I was thinking with my stomach.”

I understood exactly what he was saying. Neither of us had any money to purchase food from the commissary, and being vegetarians we received less food to eat. So, hunger was a common thing for us.

The lesson of our condition couldn’t have been more obvious. There we were locked in that cell, forced to face the reality of our poverty. We were without resources, nor control over the amount, the quality, or the nutritional content of our food. The little they did give us caused my cellie and others like him to bring the problem into the cell, instead of challenging the amount and quality of the food with the guards; thus focusing the problem away from the cell and each other.

Hunger can bring out the worst in people. To be hungry and confined to a cell with another hungry person, things can get violent in an instance.

One day, I was lying in bed reading a book. In the distance, I could hear the food cart approaching as they fed each cell. When the cart arrived at our cell, my cellie was the one who was standing by the door. He was given the food trays and he placed them on the table without sizing them up. The officer then passed him two bananas. I didn’t get up to eat. Instead, I continued to read while my cellie ate his food.

When the food cart left the range, I heard some angry voices arguing. At first I couldn’t understand what was being said, but as I continued to listen, the voices became clear enough for me to understand that the argument was about food.

One inmate said angrily, “How come you always get the best tray? My tray is messed up.”

The other voice responded, “That’s not my problem.”

This didn’t satisfy the one complaining. He became even more vocal in expressing his anger. “Look at this small banana. You always get the big banana. I’m tired of this shit.”

I’m not sure who attacked who, but it was clear that they were fighting each other for the bigger banana.

The treachery that cell life unleashes is a microcosm of the “dog eat dog world” that led to prisoners becoming prisoners in the first place. The sadness of these events remind me of the Bob Marley song “Ambush in the Night” where he sings, “Through political strategy, they keep us hungry. And when you gonna get some food, your brother got to be your enemy…”

The conditions in the SMU are dangerous. Not because the convicts are dangerous, but due to the highly experimental nature of the program. The term “non-punitive” is word-trickery used to disguise the torture of inmates by gassing them and using four-point restraints until they urinate and defecate on themselves, and cell fights that have caused the death of inmates who had been forced into cells with others they are not compatible. Consequently, prisoners have died from injuries sustained when they were attacked by their cellies while they were in restraints.

One inmate was alleged to have killed his cellie by stomping him into oblivion while he was in restraints. Another inmate was alleged to have killed his cellie by strangulation. When we hear about these types of violence being committed, we most often never hear about the role prison officials play in instigating these incidents. It is well known to prisoners that when cellies seek to part ways to avoid bloodshed, the usual retort from some guards is that they “don’t see any blood.” This was evident in my own incident with a cellie. While certain guards occasionally give extra food to treacherous inmates to attack upstanding prisoners who may be a source of problems for the guards.

After completing the SMU program in June 2011, I was transferred to the United States Penitentiary, Atwater (USP Atwater) in California. I arrived in the July of that year. The cell politics at USP Atwater were just as treacherous as the SMU. After only about thirty days in general population at USP Atwater, I was placed in the SHU for killing my new cellie. I was kept in the SHU for five years. I was then transferred back to the ADX. This should partly explain why I’m writing this letter here at the ADX. As for the sequence of events that led to the death of my cellie, I will address that at a later date.

Edgar Pitts

Previous Post

3 Comments

ABC

July 15, 2021 at 9:27 pmI have done time in federal prison, and I had a bottom bunk pass, and it would have been a problem for me, if I had been put in a cell with someone who did not have a bottom bunk pass, but still demanded to have the bottom bunk. I understand that it is difficult to get a bottom bunk pass, but in this case, the writer was the one who did NOT have the bottom bunk pass, and his cell mate did. Since many people DO have bottom bunk passes, I feel like this would continue to be a problem, if you don’t have one, and you demand to have the bottom bunk. It would have been better to pursue this through medical, instead of just demanding that your cell mate gives you the bottom bunk.

N Hardt

December 28, 2019 at 3:17 pmLady P

I don't think you cleared your mind looking enough.

First, I can not claim that I know what it's like to be a convict, but I can reasonably deduct that there are many dynamics to survival and daily life while imprisoned.

The author to me, has portrayed a picture of our failed INDUSTRIALIZED prison complex. When money is more important than rehabilitation and you treat humans like shit this story is the result. This system is a perfect look at mand inhumanity towards man.

Lady P

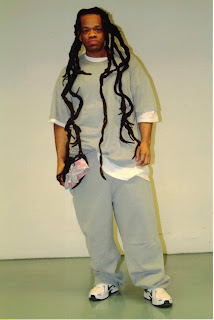

December 28, 2019 at 12:20 amI took my time to write this reaction because I wanted it all clear in my own mind. I know it will probably not be published on the website but here goes. Ok, so, the bullet in the leg makes it “impossible” to climb to the top bunk but the writer can stand on the cellmate’s neck without problem. The writer claims to be “poor” but those shoes look pretty good to me. There are ways to have another inmate assigned to be your cellmate other than the immediate complaint, threat etc. FOLLOW CHANNELS!!! No, violence must rule! This essay seems to show the public the institutionalized thinking that makes the rest of us say, “pay whatever cost you have to, those ‘people’ do not belong in society”.

Just my 2 cents.