2019

Preface:

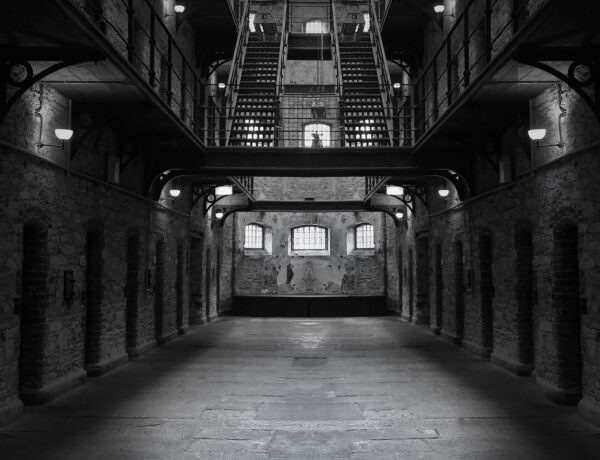

There are chunks of time missing from the year I spent caring for Lefty in the age of Corona. A sort of wilful amnesia to keep from going insane. What happens to our psyche is heart-breaking; To live life incarcerated is to know continual loss. But our memories teach us something incredible: to know that everything is fragile and can be lost in an instant. It is hard-earned wisdom every inmate learns.

===============================================================================

In early 2019 I volunteered to work at the prison hospice caring for infirmed inmates that could no longer care for themselves. I was called for an interview. It was brief.

Counselor (without even looking up from her notebook): Thanks for coming in, would you have any issues against cleaning up feces?

Me: No

Counselor: Training starts next week

Training consisted of a workbook and three two-hour videos. No test. I passed that too.

I waited three months to be assigned an inmate-in-need. I didn’t recognize the name on the work card (aka timecard) but knew Lefty right away. I’d known Lefty for years; we lived in the same unit for two years before I was sent to the Hole for a misunderstanding with my cellmate of what constitutes stealing versus borrowing. He was from the greatest generation with an easy-going demeanour and ravenous appetite for books. Coming in at around five-foot six and two hundred pounds he looked like a perfect oval with a no-nonsense crew cut. Oh yeah, and he was missing his left arm.

Lefty: Leo! My man. How the hell are you?

Me: Better than you if they got you holed up here.

Lefty: Yeah, the food finally got me. They say I got colon cancer. Stage 2.

Me: Damn! (All the training paid off with my excellent bedside manner.)

Lefty: You still trying to be some kind of writer?

Me: Some kind. You still reading everything in sight?

Lefty: I’m trying, but…well, you’ll see.

I did not want to see. I was scared of seeing. We stopped with the pleasantries and got down to business. What can I do? How can I help? I was ready. Put me in, coach. Yeah, he said, get a pen and paper. I’m on it. What do you need? Give me a list of needs, write your final wishes? No, he said, write down all the names of all 50 states. What, why? I asked. Yesterday I tried and couldn’t; I want to know if I am getting dumber, he explained.

The truth is Lefty looked good, he had a healthy appetite, liked to joke and was generally the same guy I remembered. He didn’t really need me. Mostly we played scrabble and squabbled over Trump and this new virus on the horizon: COVID. Sometimes, later in the evenings, after his meds began to kick in, he would become more introspective.

Lefty: If you say you’re a writer, then write. I never see you writing. Real writers write every day. It’s a passion and a job. You can’t half-ass it through life.

Me: How do you know I’m not writing back at my cell house before I come here or after I leave? I may be whole-assing it.

Lefty: Are you?

Me: I am not.

Lefty: Tomorrow is a mirage, don’t let it fool you.

Those late-night conversations led me to learn that both Lefty and I were losing battles with depression and had searched for answers at the bottom of bottles. Although twenty years my senior, we both had lived mirror lives struggling with addictions and demons that led us to prison. We both tried to run away from ourselves by volunteering to fight in dirty deserts overseas only to learn we cannot outrun what lives within you.

No work today, Lefty has an appointment with his oncologist. They’re going to stick a tiny camera up my ass, he tells me, they could at least offer to buy me dinner first. Oh, Lefty, I lament, again with the dad jokes?

Lefty had begun complaining to the prison’s health care team about his pain for years, but it wasn’t until he bled like a stuck pig (his words) that they even bothered to call him in for an appointment with the doctor. It would be another year and a half of begging and filing grievances before he was finally able to see an outside specialist. Cancer. Full-blown. Chemo or surgery? He picked Chemo.

Chemo is a beast; it has to just about kill you to save you. Now, Lefty needed me. He would be gone for between one and three weeks and upon his return, loaded with a bagful of adult diapers, he’d be left in my care. I fed him, bathed him, and yes, cleaned up after his feces. The first few times were hard. Harder for Lefty, I imagine. No one wants to have to depend on others for their most basic needs. I pretended it didn’t bother me. I joked. I lied.

This began a period of carefully watching Lefty’s eating habits. See, whatever he put in would certainly be coming out. I refused to let him have more than one cup of milk or serving of beans a day. He found it hilarious and would often threaten to eat after I left if I didn’t do him one favor or another. You’ll pay for it later, he’d warn me. He was good to his word, the bastard. And so, I was forced to hide food from him or threaten to quit. You don’t want Big Mama in here, do you? I’d say. He’d stay quiet, but I think he knew they were hollow threats.

After his Chemo treatments, he was grumpy and angry and tired and anxious and sometimes all of them at once. And I’m no saint. I give as good as I get. I’m not going to let anyone walk all over me…I know, I know, but this is still prison, and these walls talk. Our relationship was volatile and complicated, but it was because of him that I began to pursue my writing with more vigor.

Lefty: You’re good man, but you gotta cut deeper, closer to the flesh.

Me: What the hell does that mean?

Lefty: Raw honesty. When I hear you tell a story, you’re all heart and soul. When I read

your writing, you stay safely at the surface.

Writing to me wasn’t a hobby, it was my salvation. It started as a journaling exercise recommended by my therapist as a way to control my hyperactive borderline schizo mind. Sometimes, as I re-read my earliest entries, I realize they were the desperate scribblings of someone who had fallen so deep into the well he had lost the light. Later, they became evidence of someone trying to make sense of his past and failing. My past pulls me back relentlessly even as I float further into the bottomless pit of the universe.

Lefty once told me, you have to let go of the past. Prison is the definition of being neither here nor there. You now live tucked deep into a wrinkle of a waking nightmare. I told him, I did not want this place to erase me and aren’t we all just a collection of memories we hold? I don’t want to let go of my daughter in her pink-footy pj’s, her whole face crinkling with delight as she took my hands and put them on her tummy and commanded, “Daddy, tickle.” But Lefty chides me for reminiscing about my previous life, glorifying it, for so much of who I was is gone, irrevocably gone. He was right.

It took me a long time to process my failures, the hardest was seeing my part in losing my daughter. When I came to prison, in many real ways, I died to her and she to me. I grieved her loss, but I couldn’t let her go. She was always this thing that was taken from me. The truth was, she wasn’t taken; I pushed her away. I had to forgive myself and learn to let her go. Only then could I truly see her for the gift she was in my life. Whatever happens now or in the future is irrelevant. She will always hold a special place in my life. I am learning to live with that.

When Lefty asked me what it was like to let her go, I used the metaphor of a wild animal gnawing off its own limbs to get free when it is desperate enough. He smiled and said, “That, write that, that’s writing to the bone.”

I was with Lefty when the doctor told him the first round of Chemo had failed. He had a decision to make: More intense Chemo, intrusive surgery, or let the disease run its course. Either way he was now in Stage 3. I remember brushing some lint off his shoulder as I went into sympathetic numbness. Lefty didn’t say a word, I think maybe a brain can only process so much trauma before dissociating to protect itself.

This is not surviving a firefight or watching your wife die in a horrible accident. This is the quiet trauma that comes from sterile rooms where we come face to face with our own mortality.

This started a new phase for me: Cancer watch. I became obsessed and terrified of getting cancer. I soon found it was much more common than I thought. I’d had an uncle, cousin, and grandparent that had all succumbed to one form of cancer or another. So, it runs in my family? I wondered. Other than clean living and early testing there wasn’t much I could do to save myself. I tried my best to drink more water, plenty of fibre, and greens; paid more attention to my weight, sleep schedule, and stool. This is how my slide away from writing began.

Who can think about narrative arcs and rising actions when you’re busy reading the newest literature on new cancer therapies? I wanted so badly to be a writer – to have purpose and value, but it all seemed pointless when you live in an environment so devoid of hope. The convalescent wing of a prison, where many were simply waiting to die, was like being on an island on an island. Making matters worse were new restrictions being implemented over the fear of a new highly contagious disease coming over from China. I could no longer go to the library or buy typewriter ribbons. It made me question myself, Am I really a writer or am I the imposter I always felt I was? Was I using my writing simply as a survival mechanism against this place?

I began to doubt everything. Am I even really helping Lefty? Is my presence – that of a youthful, strong, healthy man – only making him more bitter and lonely? What must he be thinking as he watches me throw out his adult diapers, with my whole life still ahead of me? What would I think of myself? Would a part of me hate me? Yes, I think I would.

I struggled to hold on to my identity as a writer. Protect the secret chambers of my heart. I binge-wrote on days he left for appointments, but often I didn’t write for months. When I did write, I wrote dark, sad, melancholy stories of loss and failure. My mind’s eye seemed solely focused on what hurts; it could no longer see the light.

My sister, a therapist, told me I had to learn to compartmentalize. Another friend sent me a book about living in the moment, like a dog. But I am not a dog. No amount of meditating will make me one and all my failed attempts made me feel like I was living in the shadow of my worst self.

I know what grows in the shadows. Growing up our house butted up against a park reserve. My sister and I grew up climbing trees and catching bugs. At the edge of our lawn was Old Betty, a giant oak whose canopy fell shade ten feet in any direction. Nothing could grow in that shade, no other trees or flowers, its canopy too overwhelming, its roots too greedy – sucking all the water and nutrients from the earth. Big, beautiful trees get all the light.

On the day Lefty was scheduled to return from his latest round of Chemo I was pulled into the head nurse’s office and told he had tested positive for COVID and would be temporarily moved to the prison’s new “quarantine” wing. I objected and demanded to be moved with him. I’ll take my chances catching COVID, I explained.

Nurse: I can’t do that, COVID is killing inmates.

Me: Yea, that’s my point. Lefty is very weak after his Chemo. Who’s going to feed him? Who’s going to bathe him? The man is going to feel like he’s just been left to die.

Nurse: I’ll go check on him every day, I promise.

Me: Who are you kidding? You don’t even work every day!

I stormed out and immediately wrote harshly worded letters to the administration and submitted formal grievances through our internal process. It just blew my mind, couldn’t they see? Chemo would just about kill him, COVID would certainly finish him off. He was high-risk. The highest. He needed to be transferred to a hospital immediately. I threatened to write to his family, call lawyers, contact the media. Crickets.

Days passed, then weeks, I was certain he was dead. I had seen an ambulance leave the prison with its lights off earlier in the day, I knew what that meant; I could feel that Lefty’s limp body was inside. I was inconsolable. The following morning, I received a pass to return to work. I figured I would be assigned a new person to help.

Lefty’s profile is unmistakable. He’d made it. He was a wisp of his former self, skin like old leather, but still, surprisingly, with a full head of hair that looked like a bird’s nest. It was all I could do to keep from crying as I hugged him. I think the affection surprised him. I’m okay buddy, it wasn’t your fault, he told me. You hungry? I asked. I wasn’t until I just saw you, make me some oatmeal? He asked. You got it buddy.

His ordeal sparked my writing muscle if for nothing else than to write all those angry letters to the Governor and Director of the D.O.C. The Director’s office finally responded. Their letter included paperwork for a new Emergency COVID Compassionate Release program. It was a rare ray of light in Lefty’s otherwise dreary existence. I read him the guidelines; he qualified. I brought my typewriter over from my building and we set off to work on filling out all the necessary information. We would have to send off for some documents and work on his personal statement but felt confident we would be able to submit before his next Chemo appointment.

It’s been almost two years, six rounds of Chemo, and eight hospital stays since this whole thing started. Lefty tells me, I know I am going to die sooner rather than later, I just don’t want to die here. I nod my head and promise him he won’t. My writing will save him. His personal statement will be my pièce de résistance– everything I’ve been training for.

The second series of Chemo was no better than the first. Surgery is his last option. A life spent carrying a fanny pack of my own shit, he explained, that’s my best option. He also mentioned how the doctor had gently suggested simply giving up. She talked about it like she was asking me to consider giving up meat or drinking and not that she was recommending suicide, Lefty told me.

Before he left for surgery, Lefty gave me all his case files to help complete the emergency release forms. But I’m trying to keep a more balanced life so when I’m not exercising or cooking, I’m writing. A story here, an essay there. Five hundred words is a good day. A thousand a blessing. But my stories refuse to find their home; without knowing Lefty’s condition I am at a loss for closure. When I look over at his boxes of court documents, I feel a pang in my stomach and return to his personal statement.

He killed his wife. She had been riding with him on their snowmobile in the dead of night during a snowstorm when they hit a buried tree stump and were thrown into a shallow ditch. Lefty lost his arm, his wife her life. At the hospital, his blood registered at three times the legal limit. He didn’t fight them in court. Fast forward and he has served ten years of a fifteen-year sentence. All without incident. Say what you want, but I know Lefty, and yes, by definition he was a criminal, but he was not a bad person. The truth is no one is rarely all one thing. At any given moment we are all pawns of our circumstances and our past.

Almost everything I know about what happened comes from court documents and news clippings. Lefty never speaks of it, refuses to even acknowledge a question. Whatever happened that night, the pain and grief drove him to silence. As is typical of his generation, he wore a tough exterior and suffered quietly.

Rumors ran rampant. Lefty was dead, they said. He’s been gone too long. What surgery takes three weeks? What about his recovery? I protest, they’re not going to let him just leave the hospital like that. But I’m not sure who I am trying to convince. My writing drops as my anxiety rises. I just have enough motivation to mail out his emergency clemency packet. I fear it may be too little, too late.

Lefty’s Back! A co-worker yells to me as we cross paths at the Chow line. I smile hard. I thought he was gone. That night, I begin re-writing a piece I’d been working on about cooking in prison. Before bed, I prepare my things to go back to work the following day.

I see the prison doctor, a nervous old Jewish man with a supressed smile and darting eyes and a crooked, nervous posture. Even at rest, the Doc always seemed prepared to take flight. I ask him about Lefty. He has no idea what I’m talking about. I remind him. He tells me to expect a hard couple of months of recovery. Lefty will be on some pretty strong pain meds and more confused than usual. The Doc tends to half-answer questions, to speak around things. He’d been sued in the past and it’s left him gun shy about speaking directly to inmates. He has a way of making you feel both seen and unseen.

If it wasn’t for his arm (or lack thereof) I wouldn’t have known, it was him. His hair, like Einstein, was overgrown and frazzled. His eyes resting deep in their sockets with dark black bags. His cheekbones taut and pronounced over his greyish white skin. The scale shifted, the normal grew strange and the strange became normal. It wasn’t just physical either. He had become unmoored. I’m no neuroscientist, but I know trauma rewires brains. Lefty is proof. The brain can’t confront extreme change without panic blowing your reality to bits.

Bowel movements were…. difficult. It took me a few days to adjust to his new “fanny pack.” His legs were balloon swollen which confined him to a wheelchair for any movement. We would need to re-learn everything: baths, eating, everything.

Nurse Marshall caught me in the hallway one morning and commended me for my work with Lefty. She was a middle-aged biker chick with a tough exterior, but I saw her be tender and thoughtful when she thought no one else was watching. I thank her and then ask if I can speak plainly:

Me: Listen Nurse Marshall, you’re the best. You try. But not everyone does. Do you know what I mean?

Nurse: No, what do you mean?

Me: Okay, well, let’s take Lefty’s meds as an example. He is supposed to get them with his breakfast and dinner every day – cause he needs to take them with food. Well, it’s often 10am or 10pm before they come around with them. He is starving and hurting. I go ask the Duty Nurse what’s the hold-up and she writes me up for insubordination and threatens to have me fired.

Nurse: Who did that?

Me: I’m not going to throw anyone under the bus, but you can look up my disciplinary ticket for yourself.

Nurse: What if I gave you clearance to go pick up his meds directly from the dispensary when he needs them?

Me: Wow. Okay.

Lefty is different. Hard. He’s forgetful and erratic. He yells at his doctors and nurses, even me. Once, in a manic outbreak, he told me that this place is perfecting the art of dying. His new condition and dependence on opioids had made it as if gravity itself had loosened its hold. I suppose one thing is true about both prison and dying – they will deliver the unicorn: unfiltered truth.

I write angry, I write about how much prison sucks. My sister tells me I’m anticipating Lefty’s death and my brain is compensating. Lefty’s not going to die, I tell her. He’s turning into a curmudgeon, sure, but I think the meanness is making him stronger.

Jump thirteen weeks and the impossible happens: Lefty catches COVID AGAIN! My God, I think, God is angry at this man, or he is testing him. He barely survived his last bout with Corona leaving him to this day with a lessened sense of smell and taste. But, by now, a part of me is starting to believe he is some kind of geriatric superhero. Nothing of this earth can kill this man.

But I am still charged with his well-being even if I can’t do it myself. I send word to the Quarantine Wing inmate workers about Lefty’s needs along with some snacks to grease the wheels. Nothing in prison is free. They send word: He’s doing fine. Send more snacks. Up until this point we’d only had the occasional positive COVID test, and no one has died at my prison. Maybe it will skip us, I hope.

The next time I am scheduled to see Lefty I bring my clippers and a new razor. He looks like a decrepit yeti who’s been living under a bridge. I cut his hair and give him a fresh shave. He’s passed the worst of it and is starting to look like the Lefty of old. His attitude is even improving. He still gets confused easily and is constantly asking me the same questions: What time is it? What day is it? I try to reassure him. Yesterday, he thought I was the doctor — I played along and gave him a good prognosis to boot. He was happy for the rest of the day.

These days I’m rarely not by his side. My whole life is oriented towards him, and I have little time for anything else. I spend hours reading to him (his last round of Chemo left his near eyesight virtually non-existent). I’m in prison, sure, but a part of me is living in a bubble where just me and him matter. We could be on the moon for all I care.

It’s a crisp fall day and Nurse Marshall insisted I take Lefty out for some fresh air and sun. She pulls me aside and asks how I’m feeling. I look tired, do I need anything? Remember, she says, you have to take care of yourself first before you can take care of someone else. I’m fine, I assure her, I don’t need anything. She doesn’t know I’ve been helping myself to some of Lefty’s leftover pills for months. He’s almost completely weaned off.

As winter approaches, after Lefty’s last check-up, we get the news: The cancer has spread. His body can no longer fight back. He has a blood infection. They are sending him back to the hospital immediately. I get him ready and send him off with encouraging words. I’ll let your sister know what’s happening, I promise. That would be the last time I ever see Lefty.

I don’t remember much else about that day and what we might have said to each other. It had started like so many others. I arrived. I got him ready for the day and into his wheelchair. He liked to supervise while I made his bed, which he insisted on from the beginning, hospital corners and all (an old Navy habit, I presumed). I fed him breakfast, oatmeal, peanut butter with mashed banana, as usual. Then we went to his doctor’s appointment and the rest is a blur.

I would be assigned other people to help. Mac had diabetes but didn’t care. He would die shortly after I began working with him. At this point my writing had become schizophrenic and turbulent. I wrote high. It made sense to me at the time, but my writing mentor was furious and refused to work with me until I quit. And I did, but not because of her; with Lefty gone I had lost my hook-up. It took me another few months to fully recover. My last patient was a young kid from the south side of Chicago named Kin-Kin.

When he arrived, I was told he was a quadriplegic. He was heart-breaking and gut-wrenching to look at. A mangled curled mess of arms and legs. I introduced myself and his first question was, when do I get to see a Physical Therapist? I don’t know, I answered honestly, but I’ll find out.

Every nurse or doctor I tried to talk to about him spun me. Even Nurse Marshall surprised me, saying Fuck that baby killer. As a fellow inmate, I can’t judge anyone else, but I felt Kin-Kin deserved to know the truth. I explained the push back I was getting, but it only seemed to make him more determined. Eventually he would share details into his crime and have his lawyer send in an explanation letter.

He was part of a botched robbery. He and a fellow gang member had robbed a woman at gun point. His co-conspirator shot and killed the woman and her child before turning the gun on Kin-Kin – no witnesses. Kin-Kin was taken to the hospital with four gunshot wounds to the stomach. A year later he would be sentenced to 50 years for a double Felony murder. Felony murder means you were present and complacent in a murder, but not necessarily directly responsible for taking a life. The punishment is the same.

Kin-Kin was rail thin. I could pick him up easily, like a child, in my arms (and I’m no Stallone). He insisted on keeping a shaved head and trim nails. It was new for me, but I soon got into the habit. He was finally seen by the resident physical therapist and given a rehab routine. Nurse Marshall told me there was no way he would ever regain movement in his limbs. I never told him that. We worked out for hours on end. Mostly just me stretching his arms and legs while he watched and willed himself to believe he was making progress.

About a month later, I was awakened by IA (internal affairs) at my door. Pack it up, you’re going to seg (segregation aka the hole). What, why? I asked. NOW. They yelled. I spent a week under investigation. Kin-Kin had overdosed. Was it suicide or murder or an accident? No one knew. I had my suspicions, but I kept them to myself. After being released from the Hole I sent a note to the Director of the Hospice program: I quit. Sorry. She responded: You made it longer than most. Thanks for your help.

My prison had gone on full-blown COVID lockdown at this point. I did Yoga in my cell and slowly began delving back into my writing life. My writing would never be the same. This place where there are no distractions, where everything is unfamiliar, where dark magic feels not only possible, but likely had shifted something inside of me.

Then in early 2020, I got a letter and a book in the mail from Lefty’s sister. The son-of-a-bitch was still alive. Remember that Emergency Compassionate Release application I had sent? It was granted while he was recovering in the hospital. He was sent directly home after he recovered. It was a book about getting published, on the inside cover he’d written:

My Friend,

Prison takes away any hope of serendipity, but that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t try. See, unforeseen fortune is one of the secrets to a life well-lived. Keep searching for something wonderful, always believing it’s waiting just around the corner. It’s what I missed most about the world during my incarceration. I missed the sense of discovery, the constant search for the unexpected and the certain knowledge that I was going to find it; knowing I would plunge through an unexpected trapdoor and come to a soft landing in the most human side of myself.

Keep searching, Lefty.

In that moment, after months of quarantine lockdowns, I decided to volunteer to work at the prison’s Covid wing. I knew guys were hurting there – positive cases had begun to explode across the US – and I wanted to help.

EPILOGUE:

As much as it is true that prison broke me, it is also true that prison made me. I write about what I have seen and endured behind these walls because I believe it is important to share and expose what happens to society’s dregs. I wholly trust that once people learn the truth they will be driven to action.

In prison I was forced to see things from the wings, at an angle, slightly skewed. In this, I was gifted with the opportunity to view life with a new perspective, temporalities, and value system. When we’re focused on what we think we want, we’re missing the bigger picture. We’re like a horse with blinders unable to appreciate the full landscape of humanity. Our eyes will need time to adjust but correcting our vision will expand what we see (whether we like it or not) and how clearly, we see it. Perspective is not always easy to accept, but it is always worth the effort.

1 Comment

Martina Quarati

July 18, 2022 at 11:32 pmWonderful post, full of insight and life lessons. Thank you!