NOTES

1. 395 U.S. 784, 89 S.Ct. 2056, 23 L. Ed. 2d 707 (1969).

2. North Carolina v. Pearce, 395 U.S. 711, 89 S. Ct. 2072, 23 L. Ed. 2d 656 (1969).

3. Article 1, Section 10 of the Illinois Constitution.

4. At the time of this writing in 2012 it was around 49,000.

5. See e.g. Porter v. Coughlin, 421 F. 3d 141, 146-48 (2d Cir. 2005).

6. Constitution Of The United States Of America, Amendment VIII.

7. Bogan v. Stroud, 958 F. 2d 180, 185 (7th Cir. 1992).

8. Dole v. Chandler, 438 F. 3d 804 (7th Cir. 2006).

9. Westefer v. Snyder, Civil No. 00-162-GPM (7/20/10) (U.S.Dist.Ct.So.Dist.Ill).

10. Westefer v. Snyder, Civil No. 00-162-GPM (7/20/10) (U.S.Dist.Ct.So.Dist.Ill).

11. Kamel, Rachel and Kerness, Bonnie. “The Prison Inside the Prison: Control Units, Supermax Prisons, and Devices of Torture.” American Friends Service Committee. Philadelphia 2003.

12. Gustitus, Linda J. “Guest column: Tamms ‘supermax’ prison in Illinois was a mistake.” rrstar.com July 10, 2012.

13. 42 U.S.C. § 1997e (e).

14. 20 Illinois Administrative Code Section 504. 115.

15. e. g. Smith v. Shettle, 946 F. 2d 1250 (7th Cir. 1991).

16. 20 Illinois Administrative Code Section 504. 115 (d).

17. 20 Illinois Administrative Code Section 504. 140 (b) (2).

18. 20 Illinois Administrative Code Section 504. 130.

19. 720 ILCS 5/12-4 (b) (6) (West 2002).

20. 20 Illinois Administrative Code Section 504. 660.

21. Smith v. Shettle, 946 F. 2d 1250 (7th Cir. 1991).

22. Westefer v. Snyder, Civil No. 00-162-GPM (7/20/10) (U.S.Dist.Ct.So.Dist.Ill).

23. Administrative Detention Re-Entry Management Program.

|

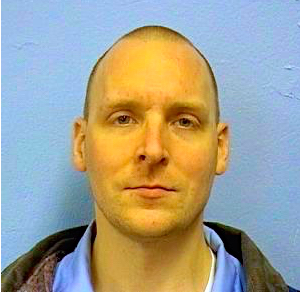

| Joseph Dole K84446 Stateville Correctional Center P.O. Box 112 Joliet Il 60434 |

|

Joseph Dole is 41 years old. Born in Saginaw, Michigan, he moved to Illinois when he was 8 years old. He has been continuously incarcerated since the age of 22, and spent nearly a decade of his life entombed at the notorious Tamms Supermax Prison in complete isolation (Tamms was shuttered in 2013 after an intense campaign by human rights groups, and the families and friends of prisoners who were confined and tortured there).

Mr. Dole is currently serving a life-without-parole sentence after being wrongly convicted of a gang-related, double murder. He continues to fight that conviction pro se, and has recently uncovered evidence suppressed by the State, which proves that the State´s star witness committed perjury on the stand.

His first book A Costly American Hatred (available at both as paperback and e-book) is an in-depth look at how America´s hatred of “criminals” has led the nation down an expensive path that not only ostracizes and demonizes an overgrowing segment of the population, but is also now so pervasive that it is counterproductive to the goals of reducing crime and keeping society safe; wastes enormous resources; and destroys human lives. Anyone who is convicted of a crime is no longer considered human in the eyes of the rest of society. This allows them to be ostracized, abused, commoditized and disenfranchised.

Mr. Dole´s second book, Control Units and Supermaxes: A National Security Threat, details how long-term isolation units not only pose grave threats to inmates, but also guards who work there and society as a whole.

He has also been published published in Prison Legal News, The Journal of Prisoners on Prisons, The Mississippi Review, Stateville Speaks Newsletter, The Public I Newspaper, Scapegoat and numerous other places on-line such as www.realcostofprisons.org and www.solitarywatch.com among others. His writings have also been featured in the following books: Too Cruel Not Unusual Enough (ed. By Kenneth E. Hartman, 2013); Lockdown Prison Heart (iUniverse, 2004); Understanding Mass Incarceration: A People´s Gude to the Key Civil Rights Struggle of Our Time (James Kilgore, 2015); Hell is a Very Small Place: Voices from Solitary Confinement (The New Press, 2016). Mr. Dole´s artwork has been displayed in exhibits in Berkeley, CA, Chicago, and New York. He has also won four PEN Writing Awards for Prisoners, among others.

He is both a jailhouse journalist and jailhouse lawyer, as well as an activist and watchdog ensuring Illinois public bodies are in compliance with the Illinois Freedom of Information Act.

You can see more of his work on his Facebook Page He will respond to all letters.

|

No Comments