By Chris Dankovich

In a modest hall covered in snow on the main campus of the University of Michigan, a mostly-volunteer staff of professors, graduate and undergraduate students, and a Canadian hockey player take some time to answer several letters before getting back to work sizing, matting, and organizing all manners of art from some of the best artists in the world (and others who show much promise). Canvases adorn the coving around the walls. Decorated papers, big and small, lay on tables. Bobbleheads of international figures made from soap and toilet paper stand on desks. Hand-carved leather purses and knitted skeletons are placed anywhere else there is room. Trips have been made to the archipelago of over 30 prisons across the state to collect the works – some further from the college as Philadelphia is by drive. Meetings have been held with the inmates involved, for some these were their only contact with the outside world. Allocations were made for artists in isolation. All of this to create the world’s largest show and sale of artwork created by the incarcerated, and one of the most fascinating, interesting, and unique art shows in the world.

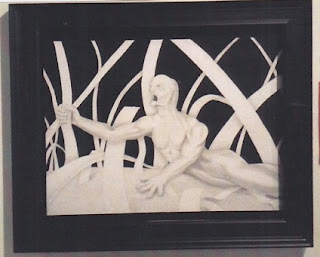

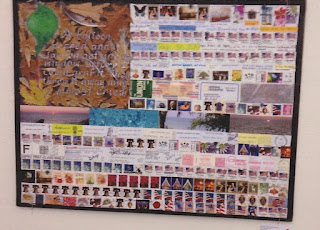

|

| Art Exhibition Submissions by the Author |

As landscapes, dreamscapes, scenes of fantasy and of the ordinary get recorded and tagged, plans are made for each artwork’s place in Duderstadt Center Gallery. Overseeing all of this is Ashley Lucas, known internationally for her work in theatre, and as the head of the Prison Creative Arts Project (PCAP) for the past five years. Under her watch, the art show – PCAP’s biggest event of the year – has become the largest it has ever been, displaying hundreds of artworks by nearly as many artists with a perspective unique to the art world. Her husband, Phil Christman, teaches English at the University of Michigan, and is the chief editor of the annual Michigan Review of Prisoner Creative Writing, now in its tenth year (a “best-of” from all previous years is the theme for this special edition). The couple took over PCAP and all of its programs from founder Buzz Alexander and his wife, Janie Paul, who encouraged rehabilitation, restitution, and restorative justice through the arts for decades. In addition to the exhibition, PCAP hosts creative writing, drama, art, art history, music, and photography workshops inside of prisons throughout the year.

|

| Art Exhibition Submissions by the Author |

PCAP came to life in 1990 when Buzz (as he asks us to call him), as a professor at the University of Michigan, began working with a new theatre group at the women’s prisons in Michigan. From there, he envisioned an expansion to spread theatre as a means of expression to male prisons. Over time, he worked in other forms of expression, notably the creative writing classes – where I learned to write creatively when I was 17-years-old at Thumb Correctional Facility –, and, in 1996, he founded the Annual Exhibition of Art by Michigan Prisoners. Hundreds of artists from across the state have the opportunity to display and sell their art once a year at the exhibition, also known as “the art show”. The show regularly leads to hundreds of sales, equivalent to tens of thousands of dollars; with all of the proceeds going first towards restitution, and any remaining profits going to the respective artists (relieving burdens placed on family members of the incarcerated). In this way, it also allows the prisoners to give back to the community, paying restitution he/she would never be able to pay off while incarcerated otherwise.

|

| Art Exhibition Submissions by the Author |

The art show also marks the release of the Review of Prisoner Creative Writing, which displays the best essays, stories, and poetry written by those incarcerated in Michigan prisons. Humor, sadness, remorse, and a striking amount of talent pervade the pages. This publication is also a special example of the restorative justice that PCAP provides to our society: not only encouraging future citizens to better themselves through art, but also by providing opportunities for educating youth outside of prison (as students at the University of Michigan learn the editorial process as a part of Phil Christman’s English classes).

The canvasses are matted and placed on the walls of the gallery. Stands are positioned to display the clocks, purses, sculptures, and other three-dimensional art. Invitations go out to special guests, like the director of the Michigan Department of Corrections, prisoners’ families, and past art buyers. Speeches are prepared for opening day. Docents are selected and briefed. Beginning each year at the University of Michigan at the end of March, everything is set for one of the most unique events on the international art world’s calendar.. All are invited; and all who attend will be impressed by the artwork, as they also simultaneously help change lives and restore our communities!

For more information on PCAP, the Annual Exhibition of Art by Michigan Prisoners, or the Review of Prisoner Creative Writing, please visit www.prisonarts.org.

2 Comments

A Friend

April 10, 2018 at 1:32 pmThe following comment is from Chris Dankovich: I thought maybe my experience with art could help expound upon your question. I had no experience at all with art on the outside, though I spent more time doodling in school than taking notes. My own start in art, which is very frequently the case in here (as if you have any potential then people will act as your patron), was drawing tattoo letters and art. The most common requests were crosses with banners, laughing and crying masks with the words "Laugh Now, Cry Later" (probably the single most common tattoo done in the joint), and skulls. I learned depth by drawing prison bars, another common theme. From there, I gained an interest in art in general, and used to flip thru old donated sets of encyclopedias to find articles about artists and artworks. After I transferred prisons, an incredibly talented artist saw my work and started encouraging me and gave me my first paints and brushes. He taught me a lot, though I never came close to the photorealism he could produce. The art shows encouraged me to keep producing and learning and improving.

At first I did a lot of pieces with something about prison in the work. I had it in my system and had never had an outlet before, so almost everything was somehow prison-related. Now I challenge myself to create other things, whether inspired by my past, something I see in a magazine or book, or (for me most commonly) dream images. Most of the prison artists I know follow a similar path.

And a bit of our work is constrained by medium. At least in my state, we're not allowed oil paints or exceptionally large canvases. We're also limited on the amounts of supplies we may possess at a given time, and by price. All that affects our work in subtle ways too. Also, we're not allowed to in any way recreate anything within the confines of the prison (like specific buildings or trees) or anything within view of the prison (like the landscape or things outside the fence, or any direct security feature). So we have to take our inspiration elsewhere.

piscator

March 22, 2018 at 3:35 pmMr. Dankovich,

Thank you for this informative article!

I find myself continually agog with with the creativity and talent of prison artists. At the same time, I've often wondered how those artists find sufficient outlets for their work. So, it was great to learn about this exhibition and the PCAP program.

I'd love to learn more about the writers and artists in these programs. I'm especially curious as to how they choose subject matter. Is the subject always 'prison?' If not, how do prison bound artists transcend such an overwhelming environment? What do they draw upon?

I hope, in the future, you and your confreres at MB6 might delve a little more into that. I certainly would enjoy learning more about producing art; in what I take to be a rather challenging environment. And if I'm wrong in that, I always enjoy learning that as well!

Sincerely, Piscator

If I've missed this topic on MB6, I apologize; still I'd sincerely like to know more about the process of producing art in prison. That is, more about the artist's smotivations, Can priAs I learn more about these programs another question that arises in my mind pertains to subject matter. Do prison artists tend to deal exclusively in prison subjects? If not, how do they manage to s it f not, how do thIf this and that and more a