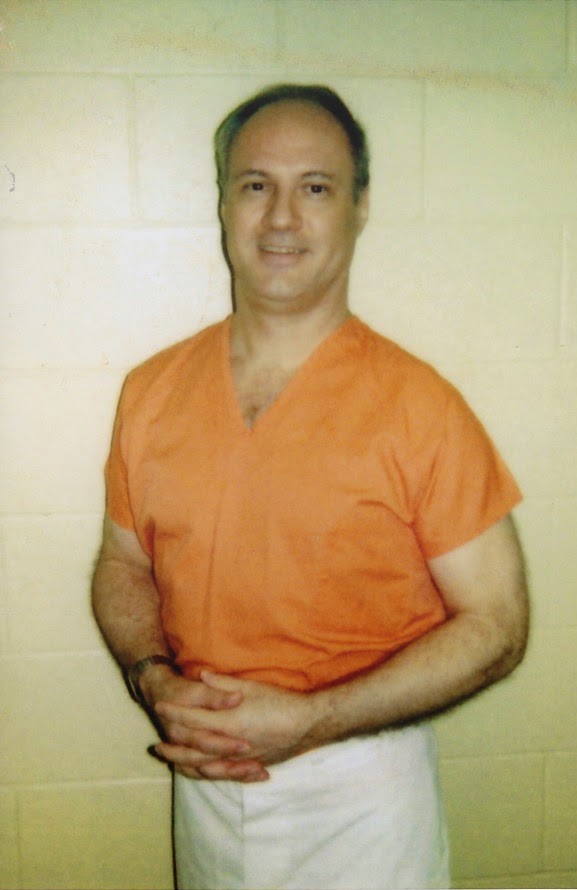

By Michael Lambrix

Sometime shortly after Thanksgiving in late 1970, when I was ten years old, my father unexpectedly told me that I was to go with him to look for a Christmas tree. I didn’t want to go, especially when I realized that it was only going to be him and me. I was afraid of him and for good reason, as he had already tried to kill me on more than one occasion. But I didn’t have a choice, and I knew only too well that even so much as a hint of resistance would be quickly met with severe physical discipline, especially since he had already been drinking.

In silent obedience I climbed into the passenger side of our old 1959 Chevy station wagon and as I closed the door and my father got in on the other side, I leaned against the door as far away from him as I could get, with one hand resting on the latch just in case it became necessary to quickly eject myself. With a turn of the key the engine was brought to life. I always loved that old wagon, a one-year wonder of the age of automobile extravagance, with its rear wings wide and long stretching all the way to the back so that even when parked, it looked like it could fly. And as my father pulled the car from the driveway and out on to the road, as only a child could, I quickly overcame my fear by imagining that we were about to take flight, and my one hand that was on the door latch drifted up and out the open window and as the cool air blew in, my flattened hand extended outward glided in the wind like an airplane in the sky.

Dad never was one for talking and we drove in silence. Going to look for a Christmas tree didn´t mean going to town, as he never bought our tree. Rather, we took a back road north and then westward away from Novato, into the San Geronimo Valley, where the farms and ranches of Marin County were hidden in the rolling foothills amongst roads that twisted and turned seemingly forever, all the while looking for a small tree that would serve the purpose. From time to time, I would point towards one I thought might be worthy, desperate to win my father´s approval and all but shout out “How about that one?” but he never slowed down or even looked, just continued to drive along in silence, steadily sipping from whatever alcoholic spirits he had in that cup nestled between his legs.

The old Chevy strained as it climbed up a small hill, and with a momentary roar of the barely muffled 348 V-8, Dad quickly downshifted and gunned the accelerator and we picked up speed. As we reached the crest and started downhill, just as the dark beaten and broken blacktop of that two lane back-road out in the middle of nowhere took a gentle turn to the right, a group of deer leaped out from the brush along the side of the road, not more than a few car lengths in front of us, and attempted to cross to the other side.

For reasons only Mother Nature knows, one of the group, perhaps the smallest one of all, suddenly stopped in the middle of the road and stared into the fast approaching headlights and I felt my anxiety rising as I wished with all my might that it would move, but it didn’t. Where any other person would quickly apply the brakes and take evasive action to avoid imminent collision, with a gleeful shout, my father pushed down hard on the gas, propelling the old Chevy faster and the car collided with the deer. At the last instant before impact, it desperately jumped just enough so that as the tons of cold Detroit steel crashed into its body with brutal force, the deer´s head slammed violently down on the hood of the car only a few feet from where I sat motionless and afraid, and then it was gone.

In that very instant my father slammed on the brakes and as he did, I was caught unprepared for a sudden stop and violently thrown forward, hitting my own head against the steel dash. As I sat up dazed and momentarily confused, the car came to a stop and my father reached towards me. I pulled back instinctively, as I knew I was about to be assaulted because it had to be my fault, somehow, that that deer jumped out in front of the car.

But to my surprise, Dad was as joyful as a small child on Christmas morning and filled with a happiness that was all but infectious. Dad grabbed me by my jacket and pulled me out of the door, half-dragging me up the hill towards where the deer had landed. There it lay, barely on the side of the road, quivering and struggling to breathe with crimson red blood flowing from its nostrils. I froze, staring down upon this helpless creature and watched in horror as my father pulled his buck knife from the sheaf he always wore on his waist and without hesitation he grabbed the deer´s head by its ear and pushed the point of the knife blade straight down deep into the side of its neck, and just as quickly, pulling it straight back out and as its head fell back to the ground, its eyes looked upward and momentarily met mine as it shook and quivered one final time before going dark and cold.

Perhaps offended by my lack of shared exuberance, I was unexpectedly rewarded with a backhand blow to the side of my head and a stern order to help him throw the now still warm, but lifeless body, in the back of the station wagon and in uncomfortable silence we drove home. The next morning the cold carcass hung from the rafters in the garage. With surgical deftness, my father butchered the flesh from its bones, and for weeks to come we ate the meat at our family table.

But that deer did not die that night. It lives in my memory, and I continue to see that desperate look of a wounded and trapped animal as it struggled helplessly in the eyes of those around me.

On December 17, 2012, I was into my second week of being in “the hole,” which is what we call the solitary cells on the designated disciplinary confinement floor. I was sentenced to 30 days in the hole because I failed to sit up on my bunk during noon count. In all the years I have been on Florida´s death row (read: “Alcatraz of the South” Part I and Part II) it was never required, but on that particular day it was demanded of me for no other reason but as a pretense to send me to lock-up because I had dared to offend the powers that be by writing a blog about the then recent reign of terror that had swept the prison under the administration of Warden Reddish, culminating in the death of inmate Frank Smith a few months earlier at the hands of the guards.

While in the hole, we have no privileges. Our T.V.’s, radios, MP3 players, all reading material except bibles, and all non-state issued food become contraband and are stored in the property room until our disciplinary confinement term is complete. We are allowed minimal writing materials and essential legal materials, and nothing else.

Although I don’t have an extensive disciplinary record, I was not stranger to doing time in lockup. Sooner or later, we all go, some more than others. It is simply part of doing time. For most of us, you do whatever amount of time they give you, and on Death Row, regardless of how petty or insignificant the alleged infraction might be, you will always be sentenced to the maximum amount of disciplinary confinement allowed.

On one side of me was an elderly black man by the name of Sebert Conners, who, in all the years I’ve known him, has been a regular fixture in lockup, repeatedly written specious disciplinary reports for what I (and others) believe to be retaliation against him for daring to speak out when the guards were brutally assaulting prisoners almost daily, leading up to the murder of death row inmate Frank Valdes in July 1999. Nine guards, including a high-ranking captain, were arrested and formally indicted for first-degree murder, and the other guards never forgot Conners played a significant role in that. (See: Frank Valdes v James Crosby, et.al., 450 F.3d.1241 (11th Cir. 2006) graphically detailing the violent assaults leading up to the death of Valdes and how Conners played a role in bringing it to light).

An then there are always the “bugs” in the hole – mentally ill inmates who suffer from various forms of paranoia and psychosis, typically ignored by most prisoners and guards, but still kept for extended periods of time in the hole when a guard who is not so tolerant or understanding decides it’s time to break them.

One of those at this particular time was Michael Oyola, who, since coming to Death Row, has made frequent trips to the psychiatric unit out on the main compound and is regularly kept on psychotropic medication in an attempt to manage his psychosis (butmore often than not it doesn´t help).

I was housed in a cell immediately adjacent to Oyola when we heard the front of the cellblock door open and about the same time, the ventilation fan was turned off. When you´ve been around a while, you know it’s a bad sign when the ventilation fan goes off. If they were working on it, we would have heard the maintenance crew in the pipe alley behind the cells where all the plumbing and electrical fixtures are. We didn’t.

An unnatural silence fell over the cellblock. Even the bugs knew something was up. It didn´t take too long before we first heard the murmured voices near the front door, then none other than the Warden herself led an entourage of guards and staff down the walkway, and as I sat watching them come, my own heart skipped a beat or two as I noticed most of them were carrying the blue fabric face masks they wear when gassing someone. One guard had a large red can similar to a fire extinguisher that we all knew held the chemical agent they used to gas inmates. Another held a small video camera.

They passed my cell but then only a few feet further the warden stopped directly in front of the cell housing death row inmate Michael Oyola, and the others fell in around her. Just as I could only watch helplessly as that small deer struck by a force it had no power to defend against, I sat silently on the edge of my bunk and listened as the Warden verbally laid into Oyola, accusing him of writing her a letter demanding to see her, saying no inmate makes demands of her.

At first I could hear Oyola politely protest, insisting that he meant no offense, but needed to see her as he felt he was being treated unfairly. But with skill that comes from years of climbing the ranks, the Warden methodically verbally assaulted him, until finally Oyola realized that his fate was already sealed and nothing he could say would matter, and he told them to do what they came to do.

The warden then stepped aside, and instructed the officer holding the video camera to turn it on. The officer holding the large canister of gas stepped forward and they blasted Oyola with it.

I had already moved to the back of my adjoining cell, but still remained not more than a few feet away, and there was no escaping that ominous orange cloud as it rolled in like the San Francisco fog, quickly filling not only Oyola’s cell, but my own, and the other surrounding cells, too.

In all the years I’ve been locked up I’ve never been personally targeted for a gassing, but I was no stranger to it either, as in recent years the use of industrial strength chemical weapons on prisoners has substantially increased. Inmates in confinement units would inevitably experience the full effects of this form of torture, either as the primary target, or simply because it’s your poor luck to be housed near someone else who has been targeted.

As that orange cloud filled the air around me, I staggered to my sink to reach for my washcloth with the intent to use the wet rag as a filter, only to find that they had also turned the water off. Without hesitation I dipped my wash cloth into my toilet – fortunately I had flushed earlier and there was nothing floating in the stainless steel bowl – and then covered my mouth and most of my face with that wet rag, all the while mentally admonishing myself to breathe through my mouth, not through my nose. If you were stupid enough to take even one breath through your nose, the gas would fill your sinus cavity and you’d suffer for days.

Coughing and hacking and barely able to breathe I dropped to my knees in front of my toilet, feeling as if I had to puke my guts up but only suffering through a series of physically painful dry heaves as my body protested against this unwelcome invasion. I was faintly aware of similar sounds coming from the cells on either side of me housing Oyola and Conners.

It never ceases to boggle my mind how the world united in outrage and condemnation when the media exposed the barbaric treatment of Iraqi prisoners at Abu Graihd prison, and stood just as united when calling for a prohibition of water-boarding and torturing of alleged “terrorists” at Guantanamo Bay, and yet every day, comparable forms of torture are inflicted upon American prisoners in American prisons and nobody seems to care. In fact, many openly advocate for the abuse and torture of American prisoners under the pretense of administering justice.

If ever a person is exposed to this form of deliberate gassing, they would know that perhaps water-boarding really is not all that bad after all. The physical effects are the same – struggling to breathe as the chemical agents fill your lungs, your body involuntarily convulses uncontrollably as your eyes water and burn – and you dare not rub them because it magnifies the effect. You are rendered unable to move, and when they finally stop spraying the gas, the effects remain for hours and the burning and the taste last for days. And it´s a normal part of being thrown into any confinement housing unit in any prison in America.

At times like that, I smile to myself as I repeat the words of the philosopher Freidrich Neischze: “That which does not kill me can only make me stronger,” and I find a momentary source of strength in those words. They impose a profound truth. I am on a long journey through the many levels of a man-made hell that few could even begin to imagine.

In the worst of times, I look back at what I’ve already survived and recall the many times I found myself housed on Q-wing (briefly re-labeled X-wing), at Florida State Prison. Even the most hardened of convicts were broken by the brutal conditions of FSP, known to many as the “Alcatraz of the South.” Back then, nobody came straight to FSP except those sentenced to death. The rest came only after they were deemed an extreme security risk and could not be housed in any other prison.

On the lower floor of Q-wing is Florida’s death house, where those scheduled for imminent execution are held until they either get a stay, or are put to death. I’ve spent my time on death watch, coming within hours of execution, (read: The Day God Died) and know that floor too well.

Above that death house are two other floors, with six cells on each side of each floor. Each of these 24 super-max cells is itself an individually sealed concrete crypt, holding prisoners who have assaulted or killed guards, or just had the bad luck of stepping on the wrong toes, often for many years at a time.

This prison within a prison has only one purpose: to break convicts. (See: “Locked Alone on X-wing” by Meg Laughlin, the Miami Herald, Sunday May 30, 1999.) I did my share of time on each of those floors. The confinement cells here at UCI, even with all the physical deprivation that comes from months of solitary confinement, seem like a Four Seasons resort compared to Q-wing. Despite the periodical call to close that wing down (see: “End The Barbarism at Florida State Prison,” editorial, The Miami Herald, May 30, 1999), those cells remain in use.

But there are moments in time when I find myself helplessly gasping for breath as the toxic cloud of chemical agent overcomes me when I find myself actually missing the extreme solitude and deprivation of Q-wing. In the hours that pass after they’ve left the wing, when that ominous cloud finally settles down to a thin layer of powdery dust that blankets everything, and the ventilation fan and water are turned back on, and each of us in our individual solitary cell begins to thoroughly wash down every nook and crack of our cells, all the while still coughing and hacking up distinctively orange colored phlegm from our lungs, even after the days that follow, with that persistent burning in our eyes and throat slowly subsides, and even after we no longer jump up when it appears the ventilation fan has yet again been turned off, I can still see that look of fear and terror of that helpless deer in the eyes of that last man targeted for gassing.

In recent months the media has reported the widespread use of chemical agents and physical assaults to subdue Florida prisoners. A formal investigation by both the State Police (Florida Department of Law Enforcement) and Federal Justice Department (FBI) has been recently launched, looking into the deaths of at least 85 Florida prisoners and willing to expose the seemingly widespread criminal conduct by guards (See: “The Prison Enforcer” by Julie K. Brown, The Miami Herald, September 21, 2014 and “Case Ties Guards, Gangs, Attempted Hit” by Dara Kim Tallahassee Democrat, Sunday September 28, 2014). They focused largely on the death of inmate Randall Jorden-Aparo, who was repeatedly gassed by guards acting under the same warden who personally ordered the gassing of Oyola and the rest of us that just happened to be in confinement that particular day.

The week following the gassing was Christmas and for the first time in all these years, I spent my Christmas in lockup. Although isolated away from the general Death Row wings, our friends would recruit whoever they could to smuggle small bags of candy and treats to those of us in lockup, letting us know that we were not forgotten. And although the memories of that deer continued to haunt me on that Christmas day in the hole, the small group of us joined together to find comfort in each other´s company and a few of the bugs even joined in as we unabashedly sang Christmas carols, if for no other reason but to let them know that our spirit was not broken.

To sign Mike’s clemency petition, click here

|

| Michael Lambrix was executed by the State of Florida on October 5, 2017 |

No Comments