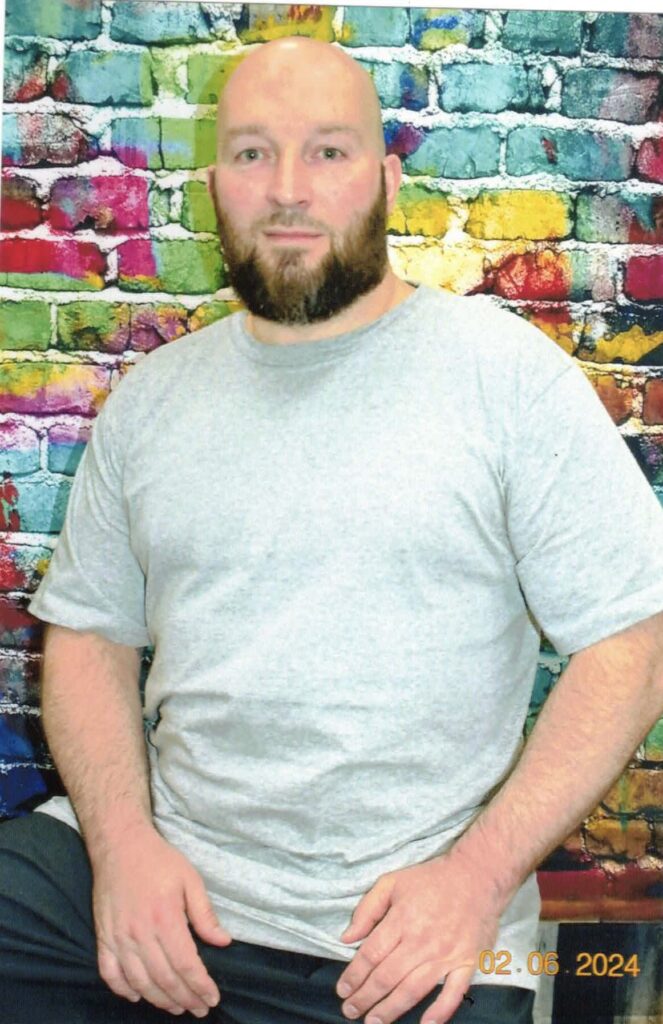

On June 7, 2016, I stood with a phone wedged between my ear and shoulder while fumbling through my address book, trying to decide which number to call. In the previous twelve years I’d only been permitted one ten-minute collect Christmas call, but there I was, with the ability to place as many calls as my funds would allow. Calling Grandma was a priority. Due to her health, living in another state and having to depend on someone else for transportation, I’d only been fortunate enough to receive a visit from her twice — so mail was our lifeline. I closed the address book and dialed her number from memory, a number older than me. The recording stated, “You have a prepaid call from Jason Hurst; press five to accept.” “Thank you for using Global-Tel Link” signaled that she accepted the call. She said, “Hey Penny.” The hesitation and tone of her voice is what I imagined had I walked into her home. That moment was the closest I had come to her front door in many years—maybe the closest I’d ever come. Since that first call eight years ago, we’ve talked at least once a week, and if I have funds on my phone account, I call more. She turns ninety-two in September and her recall of her childhood years is as clear as if she lived them yesterday.

I wish she could see my concentration and focus as she paints the picture in my mind of her and her thirteen brothers and sisters growing up in the head of the holler in Drew’s Creek. I feel the cool water running over my feet as she recounts playing in the creek with her sister Junie, and imagine my fingers knotted in the mane of the family horse they rode to deliver lunch to their dad and brothers who cut timber on the mountain. I remind her that my favorite meal was fried squirrel, gravy and biscuits from the mess I brought her when I was maybe eleven. She chuckles telling me that she and Junie used to huddle around the stew pot hoping for the choicest pieces of groundhog floating inside. My face burns with shame for my past ingratitude as she happily remembers a piece of ribbon and stick of peppermint as a good Christmas. We both laugh when she reminds me that her three-year-old Penny, armed with a garden hose, sprayed water through the open sliding door and into her living room. “It probably needed dusting anyway,” she says and assures me that I can do it again if I get out of here. Though it’s been eight years since Mom passed, a brief silence punctuates the conversation when either of us mentions her name. Grandma told me through tears, “It’s not natural to lose your kids.”

She’s from an era and a mountain people who display emotion only behind closed doors, if at all, and I live in an environment where a shed tear signals weakness and attracts aggression, so I appreciate and honor the struggle it is to push tears through many decades of emotional repression. Much of our conversations are spent laughing; Grandma has a wit and humor to rival your favorite comedian. Such as her take on a certain politician: “I’d like to pull his britches down and take a switch to his biscuits.” That’s coming from a woman I’ve never known to wield a switch. Somehow, over the phone, she teaches me patchwork quilting and cold pack canning and how to boil down strawberries for preserves. I can now make her family-favorite homemade maple or peanut butter fudge, at least in theory. How many Tupperware bowls full of that tasty fudge had I devoured on long I-77 south trips home from Grandma’s house? We bond over our shared struggle of confinement; though her prison is architecturally different than mine, it’s a prison none the less. I usually ask, “Mamaw, have you gotten out of the house this week?” I smile when she tells me, “I rode to Beckley.” I can only leave my prison for rare outside medical appointments or court, so I soak up every detail along the way. I wonder if she does as well.

She has a spot in her yard where she can sit in the shade and see the plants in her garden box. “After the sun went down, I sat outside awhile,” she tells me. I hear the same joy in her voice that I feel when I finally step out the door into warm sunshine after being denied yard time for a week or more. “You have thirty seconds remaining,” warns the prison phones operator, way too soon. “I love you, Penny,” Grandma says. ” I think about you every day, and I miss you. I don’t see why they can’t just let you out of there.” “I love you too, Mamaw, and I miss you very much. God willing, we’ll talk again in a few days.” In many ways, Mamaw is my teacher, whose diploma isn’t a dust magnet on a wall but leans on nine decades of lived experience. Each fifteen-minute phone call with her is a masterclass in life’s many lessons, without which I would be only a fraction of the Penny I am today.

No Comments