A prisoner had been dead for hours by the time the guards found him. The other prisoners knew this because they could hear the medical team talking about rigor mortis as they struggled to load his body onto the gurney.

You can’t see much from the inside of a cell in an administrative-segregation wing. One of the witnesses to this man’s passing told me that the level of architectural atomization is so high that he had lived in the same section with the dead man for weeks but didn’t learn his name was Robert Earl Robinson until he convinced a guard on night shift to show him a copy of the roster the morning after he’d died.

“It’s a bit like being sight-deprived, so you learn to listen carefully in the Hole,” this man, who spoke with me on condition of anonymity, explained. “When Warden Meador showed up with two employees of the Office of the Inspector General in tow, we could all hear perfectly well when they deployed the laser thermometer and discovered the temperature in the cell was in excess of 110 degrees Fahrenheit.”

The following day this man wrote a letter to a contact he had with the Texas Civil Rights Project detailing everything he had seen. The letter was sealed, per policies dealing with all communication between prisoners and legal counsel. The letter never arrived in Austin. Someone in the prison obviously read it, though, because shortly thereafter the administration moved him from the Mark W. Michael Unit to the H.H. Coffield Unit next door. Although both prisons are maximum security class, Coffield is widely considered to be one of the most dangerous and decrepit in the entire system. The message was not a confusing one.

The following year, overcrowding sent this prisoner back to Michael, and the story repeated itself. Another dead inmate, this time an older man who went by the nickname Caballo. Prison staff claimed the following day that the cause of death had been a heart attack.

When I interviewed this prisoner, he seemed ashamed that these two deaths hadn’t at the time seemed to be statistically abnormal.

“People die here,” he said. “It’s not a daily occurrence, but it happens enough that it becomes a part of the background noise. You become inured to it.”

It wasn’t for six years that he realized he was very nearly wrong about death not being a daily occurrence at the Michael Unit: Robinson and Caballo were just a fraction of the 103 men who died at this prison in 2018.

If that seems extraordinarily elevated, it is.

No other prison in the system had comparable deaths that year, save for the main prison hospital in Galveston, where the sickest inmates are sent after their conditions become too complicated for the regular clinics.

The Michael Unit is among the class of facilities developed and built during the prison construction boom of the late 1980s and early 1990s when tough-on-crime rhetoric dominated the conversation. Many such prisons were built, and it is within a comparison of this so-called “model 2250” style of lockup that the true abnormality of these figures becomes apparent.

The Texas Department of Criminal Justice lists seven causes of death in the public records: illness, accidental alcohol/drug intoxication, accidental injury to self, accidental injury by other, suicide, homicide, and a catch-all “other causes” category. In most of these categories, Michael Unit’s numbers were on the high end, but within shouting distance of the mean. In one category, however, that of illness-related deaths, this facility stands out as an extreme outlier.

This was the question that began my investigation. What was going on here?

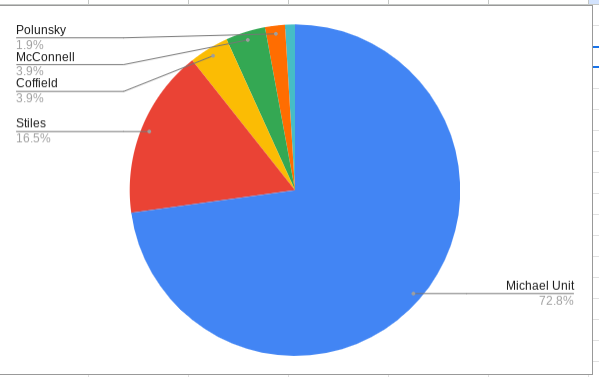

2022 ILLNESS DEATHS

In 2022, Michael Unit reported 75 illness deaths. At units of similar size, layout, and inmate population, the illness death data included four at Coffield, one at Connally, four at McConnell, two at Polunsky, and 17 at Stiles.

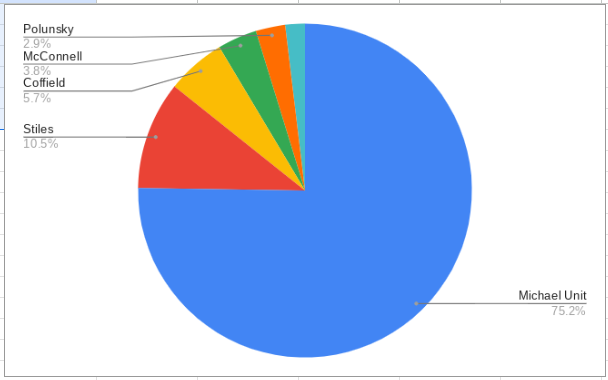

2021 ILLNESS DEATHS

In 2021, Michael Unit reported 79 illness deaths. At units of similar size, layout, and inmate population, the illness death data included six at Coffield, two at Connally, four at McConnell, three at Polunsky, and 11 at Stiles.

2020 ILLNESS DEATHS

In 2020, Michael Unit reported 87 illness deaths. At units of similar size, layout, and inmate population, the illness death data included eight at Coffield, two at Connally, four at McConnell, three at Polunsky, and 24 at Stiles.

We could go on with these charts, but you get the point. In 2019 Michael had 83 illness deaths, compared to three at Coffield, zero at Connally and McConnell, six at Polunsky, and 10 at Stiles.

One hundred illness deaths were reported at Michael in 2018, compared to seven at Coffield, one at Connally, three at McConnell, five at Polunsky, and five at Stiles.

In 2017, there were 57 illness deaths at Michael, four at Coffield, three at Connally, three at McConnell, six at Polunsky, and five at Stiles.

Back in 2016, the Michael Unit reported 74 illness deaths, compared to three at Coffield, zero at Connally, three at McConnell, five at Polunsky, and four at Stiles.

Here’s the email I sent to TDCJ Communications Director Amanda Hernandez regarding the death data:

I’m a freelance writer working on a story about the disproportionate number of “illness” deaths at the Mark W. Michael Unit in Tennessee Colony.

Based on data provided by TDCJ, an average of 79 deaths have been reported annually over the past seven years in this category at the Michael Unit, whereas just a handful of illness deaths are reported each year at units of similar structure and population (Coffield, Connally, McConnell, Polunsky, and Stiles).

I interviewed several people who either served time at these units or are currently housed there. No one has a good explanation for why the numbers are so much higher at Michael. Is there a hospice unit there? Is the population stacked with elderly or inmates with pre-existing conditions?

Some have said that heat and drugs could be contributing factors, but we know that the other units in the sample study also face these challenges.

What explains these figures? One obvious answer might be that the TDCJ is shunting deaths from more embarrassing categories into one that seems more superficially socially palatable. Having dozens of men die from a vague and generalized “illness” sure sounds better than admitting they had overdosed on substances the prisons weren’t supposed to have inside them in the first place. Unfortunately, I think the answer is more complicated than this, though I’m not discounting the possibility of some statistical sleight of hand.

Note that the death numbers were provided by the Texas Department of Criminal Justice, not an advocacy group. When asked why the illness death numbers are disproportionately high at the Michael Unit, TDCJ Communications Director Amanda Hernandez provided this response:

“The Michael Unit is one of our units with hospice. Inmates are transferred there so they can get the comfort and care that they need at the end of life. The other units you mentioned do not have hospice, so that is why the numbers are elevated here versus other units similar in size.”

Hospice Units

Here’s how the Michael Unit is described on the TDCJ website in terms of hospice or “end-of-life” care:

Ambulatory medical, dental, and mental health services. Medical care available 24 hours a day, seven days a week. Chronic care clinics available. Twenty-four-bed infirmary, including 22 hospice beds, one respiratory isolation room and one medical observation room. All services on a single level, including CPAP accommodating housing. Managed by [University of Texas Medical Branch].

The W.J. “Jim” Estelle Unit, about 10 miles north of Huntsville, has a comparable inmate capacity (about 3,148 plus 120 inmates in a “regional medical facility” compared to Michael’s 2,984 capacity plus 321 in a trusty camp). The Estelle Unit is spread across almost 5,500 acres and includes a cotton gin, cow/calf operation, swine farrowing, and field crops.

Estelle’s medical capabilities are described as such by the TDCJ:

Ambulatory medical, dental, and mental health services. Medical care available 24 hours a day, seven days a week. Regional Digital Medical Services (DMS) hub for electronic specialty clinics. Infirmary with 120 assisted living and extended care beds. Specialty clinics on-site are audiology, brace and limb, dialysis, nephrology, ultraviolet therapy, physical therapy, occupational therapy, respiratory therapy, optometry, ophthalmology, oral surgery, regional radiology, and regional laboratory. Type II geriatric facility with wheelchair capabilities and assisted disability services (ADS) showers. Managed by UTMB.

In 2022, per TDCJ, 24 illness deaths and two suicides were reported at Estelle. Michael’s numbers for that year were 75 illness deaths, six suicides, and one homicide. About 153 inmates died of illnesses in 2022 at Hospital Galveston.

The National Criminal Justice Reference Service reports the following, which further explains why the death toll is higher at Michael than other units.

At the Texas facilities located between Tyler and Nacogdoches, hospice inmates are housed in infirmary units that have been modified to meet the needs of patients accepted into the palliative care section. Both minimum and maximum security inmates who have certified terminal illnesses and have requested to be included in the hospice care programs are accepted. The inmates accepted must sign a “do not resuscitate” form.

The multidisciplinary team includes a physician, registered nurse, mental health clinician, dentist or dental hygienist, chaplain, and facility warden. The two State university medical schools are contracted to provide health care services to the inmates. Rather than attempting to maintain hospice units at each prison in the State, corrections officials decided it would be more practical to establish three facilities to accommodate the terminally ill.

The Michael Unit is the largest of these (22 beds). All the rooms are single occupancy. Inmates are provided with a radio and a television. Seven days a week, twice daily, relatives may visit at any time. One of the goals of the palliative care team is to reunite terminally ill offenders with family connections. When death is imminent, family members may stay in the room 24 hours a day.

So What’s The Story?

I’ve worked as a journalist since the late 1990s. I toured Texas prisons long before I was housed in one. I interviewed dozens of accused and convicted criminals and their families and covered numerous court proceedings. In 2019, I committed two felonies and found myself on the other side of the law. I was the one in handcuffs, wearing prison whites, subjected to follow the state procedures I’d scrutinized as a reporter.

As a journalist, I was disappointed by Hernandez’s answer to my public information request.

The more I thought about it, however, I realized that Hernandez’s answer was only a partial one. Deaths were elevated at the Michael Unit due to the hospice facility, but when I compared those numbers to the other hospice units and corrected for the number of beds, the numbers at Michael were still elevated far beyond the mean. A deeper truth is that people die every day in prison.

The data show that very few die in prison from violence, which is good for the TDCJ, but those of us who have lived behind the walls are rightfully skeptical. TDCJ also hasn’t claimed a death due to heat-related illness since 2012. I believe that to be false, and the federal court system is currently reviewing a lawsuit claiming that inmates are dying of heat. A recent headline declared, “An inmate’s body temp was 107.5 when he died. The state of Texas says heat did not kill him.”

Drugs And Disciplinary Cases

None of the six units in my sample study had more than one accidental alcohol/drug intoxication death per year between 2016 and 2023.

I frequently hear from incarcerated individuals who report an overdose occurring in their housing unit. Not all overdoses result in death, but it does raise the question of whether an overdose always ends up being classified as such. They could, for example, be determined as cardiac arrest and wind up in the illness category.

Let’s examine whether there’s any truth to the rumors that drugs are rampant in the male facilities of the Texas Department of Criminal Justice.

In a seven-year period starting in 2016, there were 1,458 drug-related disciplinary cases at Coffield, 886 at Polunsky, 410 at Stiles, 516 at Connally, 840 at McConnell, and 779 at Michael.

The number of cases written isn’t necessarily a linear path to death. It shows that drugs exist on these units, but the number of cases might be attributed to an aggressive officer or a new warden’s initiative to crack down on bad behavior. The category for drug and alcohol-related deaths is relatively low at all the units in my sample study. It’s the arbitrary “illness” category that stands out.

But the number of drug-related disciplinary cases makes one thing crystal clear: There are a lot of illegal drugs in Texas prisons.

Mark W. Michael Unit

A man who has been in administrative segregation at the Michael Unit for more than a decade provided the following information:

If you are not familiar with prisons in Texas, it can help to understand the configuration. Michael was the first of the newer designed units, starting in 1986. As the first and a prototype, mistakes in the design were corrected when other, similar units were built. For instance, from the outside, Polunsky Unit in Livingston looks almost exactly like Michael Unit. The inner areas can be different. Twelve building is where Administrative Segregation (now called Restrictive Housing) is. 504 total cells. Or six pods of 84 cells, six sections per pod, with 14 cells per section. It is a closed environment that is supposed to have AC, but the system has long been impaired (an after-market installation when the original failed). By comparison, Coffield is an older, red brick unit, with long tiers. Restrictive Housing over there has four tiers of cells. Like other red brick units, it is scorching hot. But it gets plenty hot here, as well.

In 2016, the 12 building here was mostly switched over to house the Mental Health Therapeutic Diversion Program (MHTDP). Five pods were designated for that program F Pod was reserved for Ad. Seg., which is where I was until 2022 when the MHTDP was sent to other units. Why? Because it was an unmitigated disaster. It was the wild, wild west back here. Often a warzone. And by 2019 a good majority of the staff were Nigerians who didn’t want to work. I think they had good intentions with the program, but the guards were not properly trained or qualified to deal with mental health patients. The last number I heard leading up to the transition in 2022 was 14 dead. Were there more? Likely so because there was a drug epidemic here as well. Did heat play a role? Undoubtedly. Men who were being treated for mental illnesses with powerful antipsychotics should have been housed in cooler environments. The opposite was generally true (in some cells the AC worked, while others, often on 2 row, did not). And in population, where there is no AC in the housing units, drugs and heat surely did not mix well.

Eric Carillo did time at several Texas units including Michael. He said drugs are rampant there. When pressed, he admitted that drugs are rampant at all of the units where he was housed. Now an advocate for prison reform, Carillo recently spoke at a candlelight vigil in Gatesville, where he was once housed at the Hughes Unit, raising awareness about deadly temperatures inside Texas prisons.

He said he witnessed a female officer collapse from the heat while he was at Hughes. It took officers almost 15 minutes to respond, so inmates stepped in to get her off the floor and provide water from a cooler.

“That was the last time we saw her,” Carillo said. “I don’t know what happened to her.”

Officers frequently break the law by selling contraband and illegal narcotics to inmates, Carillo added.

“If they want to bring contraband in, they should bring in an AC unit,” he said.

Hillary Randall also attended the Gatesville vigil in August. Randall’s husband was housed at the Michael Unit in 2023 when he began experiencing pain from an autoimmune disease. Malnourished, suffering from heat exhaustion, and dealing with untreated illness, Randall’s husband was moved to the Byrd Unit, where he died. The grieving widow says her husband suffered from Graves Disease and she believes he passed away due to medical neglect at the Michael Unit.

Randall has addressed the Texas Board of Criminal Justice about her husband’s death and says her comments were dismissed.

“She claimed there are reports of abuse, neglect, and misconduct in the agency and that the basic needs and human rights of inmates are not being met,’ according to the minutes of an April 24 board meeting.

A former Michael Unit chaplain who spoke at a volunteer training I attended acknowledged there are a lot of deaths at the prison in Tennessee Colony. He brought it up to advise volunteers to look for signs that an inmate may be suicidal. But suicide is far from a leading cause of death at Michael.

Heat Deaths And Fires

My source from the inside says it’s possible that the added stress from heat for those who are diabetic has been a problem. At Michael and several other male units, inmates are known to set fires in their cells to get attention or cause trouble. It exacerbates the heat and existing medical conditions, one incarcerated individual told me.

“Prior to 2022, and to a lesser degree after it, fires have been a major health hazard,” he said. “There are no purge fans. Fires would rage, blacking out whole pods. I developed hypertension because of that. I also have a problem with my liver and thyroid, due to the toxins. I can easily imagine how other men who were already high-risk suffered. So your variables: Bad air, especially back here on 12 building. Mental health patients who were out of control, left in hot areas while taking either powerful antipsychotics or other drugs (like synthetic marijuana). Then high-risk (often older) men with health issues taking medications that were heat sensitive.”

Again, the Texas Department of Criminal Justice has not acknowledged a heat-related inmate death since 2012.

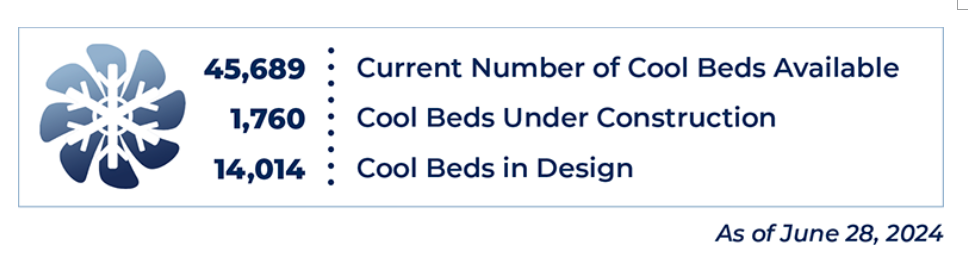

The Texas Department of Criminal Justice recently launched an online dashboard to publicly track air-conditioning construction progress across the agency following the allocation of $85 million in the 88th Texas Legislature Session last year.

As of June 28, 2024, the TDCJ has successfully implemented air conditioning in 45,689 beds across various facilities.

Currently, TDCJ has 32 units fully air-conditioned and 55 units partially air-conditioned. Be advised, as someone with personal lived experience, “partial air conditioning” is often used as a term to describe areas such as visitation, the warden’s office, and specified respite areas, while the housing pods remain convection ovens. This also means there is no heat in the winter.

Source: Texas Department of Criminal Justice

Prison rights advocates, including Lioness Justice Impacted Women’s Alliance, in April 2024 joined a lawsuit originally filed a year prior by Bernhardt Tiede against the Texas Department of Criminal Justice and Executive Director Bryan Collier. The suit alleges that the lack of air conditioning in the majority of Texas prisons amounts to cruel and unusual punishment.

Tiede, the subject of the Richard Linklater film Bernie starring Jack Black, is serving a 99-year sentence at the John B. Connally Unit in Kenedy, Texas.

Tiede, 65, suffered a medical crisis after being housed in a Huntsville cell that reached temperatures exceeding 110 degrees, the Texas Tribune reported earlier this year. He was moved to an air-conditioned cell following a court order but he’s not guaranteed to stay there.

The April 2024 filing expands the plaintiffs to include every inmate incarcerated in uncooled Texas prisons, which have “led to the deaths of dozens of Texas inmates and cost the state millions of dollars as it fights wrongful death and civil rights lawsuits.”

The advocates claim that more than 85,000 incarcerated Texans cannot access air conditioning in the summer. As temperatures rise to triple digits, tiny prison cells can reach 140 degrees.

Extreme temperatures are inhumane, a violation of 8th Amendment rights, deadly, and affect the health and mental well-being of all who live and work in Texas prisons, advocates said in a press release issued last month.

Lioness Community Outreach Coordinator Marci Marie Simmons spoke at a press conference about the lawsuit on April 22.

“Lioness has over 700 directly system-impacted members,” Simmons said. “A large percentage of our membership is still under the direct authority of TDCJ, making us particularly vulnerable to potential retaliation. Despite these risks, we bravely stand in pursuit of humane and non-life-threatening temperatures in Texas prisons.”

Multiple studies link extreme heat to higher rates of death in prisons. Other studies have shown increases in violence and suicide risks, according to National Public Radio.

“I remember laying on my bunk, wondering if I would survive,” Simmons said about spending a decade of summers in Texas prisons. “I watched women in the summertime get carried out on stretchers and get taken away by ambulances, some never to be seen again. We didn’t know what happened to them. They were just gone.”

Watch the press conference below.

For nearly 30 years, Texas jails have been kept under 85 degrees, and the recently filed lawsuit asks the court to order that Texas Department of Criminal Justice facilities be required to do the same, according to a press release issued by organizational plaintiffs including Lioness Justice Impacted Women’s Alliance, Texas Prisons Community Advocates, Coalition of Texans with Disabilities, and Texas C.U.R.E.

Texas Rep. Carl O. Sherman, D-DeSoto, proposed legislation last year supporting the installation of air conditioning in state prisons. The bill passed the Texas House but died in the Senate.

“We are trying to bring humanity and sanity to our prisons,” Sherman said during the press conference.

“More than two-thirds of our [incarcerated] citizens are in housing conditions that are inhumane. We can do better. We have the resources. We just seem to not have the compassion to address this issue.”

Texas Prison Oversight

Would independent oversight of the Texas prison system reduce the death toll? There are no silver bullets for problems this complex, but having a group of people whose livelihoods do not require the suppression of evidence unfavorable to the current directors of the TDCJ is a good place to start. You can’t begin to diagnose a solution to a problem until you have an accurate view of it, one that is firmly grounded in empirical reality.

I talked to an inmate recently who was sitting in the dayroom of the Ellis Unit in Huntsville. He detailed the scene: A man was covered in vomit. Another was lying on the floor. Several were twitching or jumping up and down, displaying erratic behavior. Smoke was in the air from people actively using drugs. In the dayroom. Where there are cameras.

There was not an officer in sight.

Wardens know there are drugs in their units. Officers and visitors are occasionally arrested for bringing drugs to prisons. Yet the activity continues.

The Texas Department of Criminal Justice is overseen by a board of directors appointed by the governor. The nine-member panel is largely viewed as the foxes guarding the henhouse. Board meetings include awards and recognition for officers and programs but there is rarely open discussion of the problems occurring in state facilities.

It has been suggested that a better structure would be along the lines of the Texas Commission on Jail Standards, which reviews the custody, care, and treatment of inmates and has the authority to shut down noncompliant facilities.

The Sunset Advisory Commission reviews some of the 130 state agencies under its jurisdiction every two years during the state legislative cycle. The TDCJ is currently under review and was last reviewed in 2013.

“Sunset refers to the process through which state agencies are either authorized to continue operating or closed down,” states information from the Texas Center for Justice and Equity. “This evaluation process is led by the Sunset Advisory Commission, a 12-member group of lawmakers and members of the public, along with a staff of about 30. The commission receives feedback from experts and the public and it shares information with the Texas Legislature, which determines whether state agencies should continue to exist.”

A Call to Action

As we mentioned in this essay about the November elections in Texas, real change is possible.

While the legislative terrain for any kind of progressive reform is challenging in this state, we managed to eke out some victories during the 2023 session. For instance, Senate Bill 1146 related to improvements for prisoner medical transportation for women passed, with bipartisan support.

Similarly, House Bill 2708, which was sponsored by Rep. Valoree Swanson (R, HD-150), Rep. Venton Jones (D, HD-100), and Sen. Peter Flores (R, SD-24), passed as well, which prevented the TDCJ from ever replacing in-person visits with video visits. You can imagine the negative impact on the well-being of prisoners if the system had ever managed to eliminate visitation, and this bill perfectly illustrates why we need the public to police the system.

We published this essay recently on House Bill 1064 (The Good Time Bill) and heard from Rep. Joe Moody’s office that the legislator plans to reintroduce it when the new season kicks off in 2025.

Here’s where your voice really matters. In a system where the foxes guard the henhouse, calls to a unit warden or Texas Board of Criminal Justice member don’t get far. Real, effective, impactful change starts with who you entrust to make decisions at the Texas State Capitol in Austin.

The vast majority of prisoners currently behind bars are going to return to the communities we all live and work in. The behaviors they exhibit and the ethics they follow are largely dependent upon the kinds of environments they lived in while incarcerated — and that is itself dependent upon the choices we make on the legislators that sit over our criminal justice systems. Change starts with your choice.

No Comments