“Solitude means being aloof from the influence of society. It may be practiced alone or in company, just as emotional dependency can be practiced alone or in company. One who is physically alone yet still under the influence of other people is not solitary. One who abandons the world in favor of isolation is still not solitary either, because the world is still a companion by virtue of ongoing relation, even though that relation be one of rejection.”

— Thomas Cleary

For over a month now, I’ve followed the spread of covid-19–from those early days of the outbreak in Wuhan, China, to the worldwide pandemic it became. That it continues to be. Fear of sickness and death brought Nations to their knees. As a result, social distancing has become the norm, requiring each individual to reorient their lives–to, at times, make hard choices.

All the while my life has remained largely the same. My current housing in administrative segregation means that I am in a cell by myself, protected by a steel door with a plexiglass shield affixed to it. But I’m acclimated to this environment after 10 years, so the current lockdown and meager meals are only a minor discomfort. Even so, it is while here, as I’ve listened to news reports, or read various articles on how people are being affected by the coronavirus around the world, that I’ve spent time considering the influences and conditioning which contributed to my growth and ability to adapt in this reality.

Because I have been separated from society for so long, I recognize that my situation may be a singular one. There is no doubt that being housed in administrative segregation is atypical by even prison standards. So perhaps my overall perceptions are tainted by the restrictions I have had to endure. And yet, isn’t that the crux off the matter to some degree? Restrictions are devised with the goal to alter behavior regardless if an individual has a desire to change. The conflict arises because we are social, habit-forming creatures.

Social distancing then, or any separation from normal life patterns can have myriad effects, mentally and physically. Leading to situations on par with the Archer’s paradox: You can’t hit a target by aiming straight at it because the shaft gets in the way. Similarly, it is our desire to remain attached to what we will lose through separation that inhibits our ability to adapt to the situation.

***

A friend of mine, Jose Moreno, went through many different types of separation throughout his life. Beginning when he was abandoned by his birth parents, thus separated from the chance to know them–to have their love and support. Fortunately he was adopted by a loving couple in San Antonio, Texas.

The man Jose would, without hesitation, call his father worked several jobs to provide for the family. Jose’s adopted mother was often home, and it was with her that he forged deeper bonds.

Which were shattered into a quagmire of grief when she died. Jose was no older than 15, and even though his keen intelligence was already opening doors to higher education with his acceptance (and scholarship) to a private academy, the rest of his life deteriorated due to the separation from his mother’s love. Her tenderness. To whom could you share the grief and rage over such a loss?

Surely he deserved a different life-arc with the assistance of a mentor to find order in life. Instead Jose roamed the streets, finding a diluted sense of identity and worth through erratic behavior.

Jose suffered from an unspeakable anger–a frustration that permeated his being to the point of eluding rational thought. To find freedom from what existed in his mind and soul, he turned to drugs and alcohol. Perhaps it wasn’t the same for the others he shared those intoxicants with, but Jose sought a separation from the past, hoping to blur or even erase what swirled in his mind regarding his mother. The natural consequence was that he locked himself into a dismal reality without any consideration of the past or thoughts of the future. His perspective deteriorated, narrowing into defeatist fanaticism which impaired his true inner character.

From his mother, Jose was taught compassion and goodness, from his father, to value a solid work ethic, but a lack of life experience shattered Jose’s awareness of what it meant to be alive. The immediacy of his mother’s death lifted the veil of innocence and, sadly, served as the catalyst towards his zest and urgency to live recklessly. With wild abandon he raced motorcycles on back streets, chased women, and tried every illegal narcotic that was available.

Jose shared his stories with an understanding that he had likely formulated some sort of subconscious death wish. In such a state, his intelligence worked against him. A new conditioning based on identifying as a victim made justifying aberrant behavior normal. He had separated himself from the world once associated with his mother. Thus he detached himself from reasonably being able to discern the ripple effects of his actions.

In 1986-87, Jose was convicted of capital murder. An elaborate scheme was thought up by the group he ran with to kidnap and ransom a guy with a known trust fund. The kidnapping was successful, but the subsequent negotiations over payment led to the man’s death. Which is how, at 17 going on 18 years of age, Jose became forcibly separated from society and placed into the isolated confinement cells where those on Death Row were housed.

Did he understand his wrongdoing? In those early days, to some extent, yes. But he wasn’t ready to admit the problems that existed within. Even when thrown in a cage, away from the distractions that had helped him evade that reality, the conditioned instinct to cloak his suffering with rage and self-destructive behavior was too great.

“When I was in county jail I joined a gang because they told me they ran things in prison,” Jose once told me. “Being in that gang made it easy to get drugs or anything else I wanted. But I was out of control. I can’t tell you how much money I wasted on drugs or alcohol. And I stopped counting how many disciplinary cases I ended up with for fighting the guards, or other behavior that required them to use force to subdue me.”

For over 20 years Jose was on Death Row, in a cell alone. Eventually he came to realize that the gang truly wasn’t for him, so he separated himself. He also turned away from alcohol and drugs. Slowly he began to value others again, developing meaningful relationships with neighbors and those outside of prison. Feeling powerless over his station in life transformed into an appreciative desire to fight to live.

Jose also returned to the realm of academia, honing his mind relevant to his interest in psychology, physics, mathematics and architecture. In doing so, he rekindled the youthful passion he once had for learning with an eye towards finding purpose and meaning each day.

“I don’t know how much good it will do to learn every possible thing about physics,” he shared with me, “but at least it may motivate me to move on to what I can only call true unity.”

The fight for Jose’s life took a lot of sacrifice and dedication. Jose’s father used his life savings on the attorney whose work became the technical fulcrum to alter Jose’s sentence. But the specter of death shadowed Jose into 2008.

We discussed how he felt while waiting to be executed. “I was at the point of feeling so distanced, so alone in the world,” he said. “While on the phone talking to my dad I couldn’t stop crying. Then they came and told me to get off the phone. I wanted to argue. Surely it wasn’t time yet? But the guard told me I’d received a stay of execution. It didn’t take them long to transfer me back to the Polunsky Unit.”

Leaving his friends behind, getting into a van with armed guards, and being transferred to deathwatch on the Walls Unit was harrowing for Jose. The stay of execution was certainly a relief, and seeing his friends again was a pleasure, but the acute tension and anxiety over the underlying terror of having to endure that process again remained.

In imagining the process, echoes of other truths have been revealed:

How the State dispassionately approaches executions; How, considering Jose was barely a young man when convicted, no thought was ever given towards who he became.

The State did not care about Jose. Only that he was condemned to die. Such concepts as atonement or redemption were irrelevant. Compassion … mercy? Ridiculous! Jose absolutely cared, though, and he worked diligently with his attorney to secure a plea agreement. In short, Jose agreed to accept several life sentences in lieu of being resentenced to death. Additionally, he agreed to never accept parole. And all of the years he had been incarcerated were waived, so he did not receive any time credit.

In 2008 Jose was given a chance to appreciate being truly alive, with the idea that every sunrise was his to view, every sunset was his to enjoy. But there was a cost for such a change. He was forcibly separated from decade’s worth of relationships and memories and sent to Michael Unit. Every person that crossed his path became an event, a memory, good or bad, filling in the hours with experience instead of tedium. And he was blessed to retain several pen-pals who continued to write and support him even after he transitioned.

By the time I met Jose in 2011-12, he was kind and gentle and content. In a cell alone, his life was very ordered, managed so obsessively that he would suffer anxiety attacks when his routine was disrupted. Coming out of the cell was something he avoided, but he associated with others well enough. He could have gone on living that way indefinitely, I’m sure, but the winds of change had other plans.

In 2016, the administration of Michael Unit began taking steps to transform the majority of 12-building into the Mental Health Therapeutic Diversion Program. To do so, over four hundred men in administrative segregation needed to be shipped to other units.

Jose followed all the rumors because he did not want to leave. “You’re right about the anxiety,” he wrote in a kite to me, “I may have a heart attack long before I get transferred. The Michael Unit has gotten rather nice over the years. I just can’t imagine many other places where it could be better.” He also understood his limitations. “It’s no wonder I have anxiety as that is the most common symptom of prolonged exposure to solitary like confinement,” he shared. “I would say that I’m doing exceptionally well considering that I’m going on 30 years in seg. But relocating does stress the fuck out of me. It is a mental thing.”

It came down to the end for him; he got close to avoiding the transfer. But when they came and collected his property, he knew his fate. He also knew that he would again be separated from a place of comfort where he had made friends.

“I can’t believe you’re still here,” he wrote. “I wonder why they’re saving you for the last too? I really hope that you are on the chain for Monday morning because there is a chance we could go to the same destination. Otherwise this will truly be my last kite and then we won’t ever be able to have any long talks anymore.”

On Monday morning I stayed behind. And unfortunately for Jose, he ended up going to the place he had hoped to avoid: Eastham Unit.

They call it “The House of Pain,” which became an understatement for Jose. There was no comfort in the tiny cell with bad air. The guards were rude, the shakedowns demoralizing, and ohh was it hot!

Jose once told me: “Even though I separated from my gang, I have no intention of going to the G.R.A.D. program.” He couldn’t stand the thought of having to share a cell and walk everywhere. After 30 years he had conditioned himself to live a certain way alone.

Well “The House of Pain” caused Jose such intense suffering–most of it mental–that he finally broke down and signed up for the Gang Renunciation and Disassociation Program. A year later he was there.

Ellis Unit was another older unit and surely as hot, but Jose was simply ecstatic to have escaped what, to him, was a horror. Besides, he was originally incarcerated on Ellis up until 1998-99. Then an escape attempt took place and Death Row was transferred to Polunsky Unit. Jose lamented that fact because, he told me, “On Ellis we had more freedom. More art supplies. There were TVs, and other things that made doing time much better.” Once on Polansky it was pure lockdown status, minus the one hour each day for recreation.

Each instance of separation, social distancing, and reintegration caused significant changes in Jose’s life, requiring him to alter his conceptual views of how he was going to manage his time. The G.R.A.D. program put him through phases, where he attended classes with others and was slowly reintegrated into living in a cell with someone else. The end result was Jose’s graduation to population, to the need to walk everywhere for everything!

In essence, Jose endured over 30 years of social distancing, and then was thrust back into the more typical prison society where sacrificing time and space was necessary. Something he deeply resented. Adapting was a grueling process for him because he was mentally locked into craving a return to the past.

When he started looking beyond himself, he developed a more wholesome purpose. On March 28, 2020, he wrote his friend Ines Aubert: “I wish I could say that helping others is a joke I’m telling. But that’s the direction my life is going. I didn’t pick this for myself. If you could see my daily life you would agree. Think about this: My three daily associates that I met on this wing have all gotten beat up by their cellies. These guys have problems adjusting to prison and it’s obvious. When I see these guys–and I see a lot of them–I immediately recognize them and I try to help them by giving them all the valuable information I have acquired over the years. I helped them get good jobs, make commissary more promptly, and basically stay out of trouble. It doesn’t even cost me anything monetarily.”

After years of urging and encouraging him to embrace change and find ways to use his experience he finally found the inner strength to become a mentor to others. The mentor he never had.

Then four weeks later, on April 23, 2020, Jose died.

***

My personal journey with different forms of separation, including the intense social distancing I endure now, have led to profound changes. Some of them I am aware of, others I am only beginning to understand.

Our biological responses to the outside world are quite strong. “Hormones associated with … social connections can light up our nervous system and give us a health boost,” Jeffrey Rediger, M.D. explained in his article: Love Medicine: How human connection–or a lack of it–affects our hearts and hormones. “The results run deep in the body, down to the very rhythm of our hearts.”

Feelings of connection cause our brain to release a cocktail of hormones and chemicals–“some combination of dopamine, testosterone, estrogen, vasopressin and oxytocin,” Dr. Rediger shared. All release through the vagus nerve: the most powerful neural network in the body. “It regulates heartbeat, lung function, and digestive flow, among other vital systems. Our hearts, guts and stomachs are hotbeds of neuroreceptors.“

Experiencing a connection with others sets the vagus nerve ablaze with positive signaling. Even small moments of positive interaction with the people around us improves the neural pathways. Or as Barbara Fredrickson, a psychologist at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill would suggest, a sort of “falling in love.” To her it’s a series of “micro moments of positive resonance” experienced repeatedly. And those moments are very important, because it amounts to bonding, or working out the vagus nerve.

“The same way I work out my leg and heart muscles when I go for a run,” Dr. Rediger explained.

Social mindfulness is a profound concept, and perhaps an undervalued part of our daily lives. I mean, how often do we work on cultivating feelings of love, compassion, and goodwill towards ourselves and others? How much of our ability to be socially mindful is stripped away when we face forms of separation? Through the use of practices such as loving-kindness meditation, or LKM, it is possible to increase positive emotions. Being more positive leads to an increase in social interactions. But the opposite is also true: when we neglect to interact with others, negativity and despondency are natural results.

“[L]oneliness, social isolation or both were associated with a 29 percent increased risk of heart attack and a 32 percent greater risk of stroke,” Dr. Rediger stressed. Fewer social interactions leads to “disrupted sleep patterns, altered immune systems, higher inflammation and greatly increased levels of stress hormones.”

Even gene expression is affected.

The problem with being alone is that a greater tendency exists to see the world as a threat. Dr. Rediger made it clear that “loneliness is contagious and heritable,” affecting “1 in 4 people … and increases your risk of an early death by 20 percent.”

John Cacioppo, a social psychologist at the University of Chicago, explained in a 2016 interview with The Guardian that he would add the instructions, “do not house in isolation,” if a zoo was built for humans.

***

“It’s suffering that helps us look beyond ourselves, to find common ground with others–and appreciate the joys we otherwise take for granted.”

–Dalai Lama

A path with a new turn can cause disorientation. As time passes and the path continues in its new direction, there’s a tendency to believe it will remain that way forever. Then the truth presents itself: A path once bent is always susceptible to change, especially when it’s caused by manipulation from an outside source.

Losing control, the ability to choose–free Will–is difficult because we live, each of us, according to our morals, our principles. But we are also asked to live in a way that serves the interests of the communities we are a part of. Or, at least, we should.

If we cannot understand the joys and pains of those around us, if we cannot share in a greater community, then where shall a life purpose be found? Connecting with others requires empathy. It is sharing in the joint pain, laughter and tears that so fully reflect a passion for friendship, even love. Thus empathy leads to purpose; purpose leads to satisfaction; satisfaction leads to contentment; contentment leads to joy.

Is empathy how we can reduce the suffering instances of separation or social distancing causes? Perhaps. Archers for hundreds of years came to understand the paradox of their profession and learned to compensate. The stiffness and weight of the arrow matters. The fletching. So does the bow set up and finger release. Conditioning through practice helped those archers develop a consistent, instinctual aim.

How we condition ourselves truly matters.

Just like awareness matters: of our personal limitations, and how we affect others, directly or indirectly; of our perceptions–the tendency to judge or ridicule, to be positive or negative; of our personal needs, the sustenance to live; of the world as it is, to accept that reality; and of our ability to understand the impermanent nature of things.

Ultimately, I think, a basic need lives within the majority of us for some sort of control, ownership, or at least stewardship. To find our place in a world that can be confusing, overwhelming. But seeking order in a little corner of this big, at times uncontrollable world is complicated. Because peace is not a place, nor is it found in things. The irony of material acquisition is that it inherently works against any hope of true serenity.

Solace can be found, though–in the kingdom of the heart and soul, defended by the security of honest love and friendship and the warmth of memories. Live with the hope that the future will be better, and work to make it so. Once you’ve developed a clear sense of where you wish to be emotionally, the effort you put into being positive and more socially active will provide a deep sense of satisfaction, accomplishment, and joy.

***

Jose was a part of my life for nearly eight years, but we were only around each other infrequently. Because of my High-Security status (due to an escape attempt in 2010), I was rotated each week. Sometimes I landed in a cell near Jose. A few times I was his direct neighbor. Or I simply landed in one of the eighty-four cells on the pod he was located on. No amount of separation kept us from taking advantage of the opportunities to open our minds to each other. We wrote kites. I would coordinate with the guards to go to Jose’s day room. Or we asked the guards to place us outside together. Then there were the instances of hooking up the mic-system, talking late into the night when we were close enough to do so. After he was transferred in 2016, we continue to stay in touch because it was important to us.

I’d love to say that I came to know him, but is that true? Perhaps his patterns of behavior simply matched my expectations: what I felt were indicators that a person had changed and grown, bettering themselves. I did not live in Jose’s mind, though, so my perspective could be interpreted as an arrogant presumption if I were to demand it was true.

Ultimately, appreciating Jose’s perceptions toward the experiences he lived through is key. I can only relate that I believe he shared the truth with me as he knew it. My surface reasoning does not have to compete with his inner complexity, or challenge how he might have changed. I felt that he did. His words resonated. More than anything, I feel blessed to have been included in his life journey.

Much like I will forever be grateful to him for introducing me to Ines. She helped Jose and I stay connected, but her and I also became close friends. On May 2, 2020, she notified me that he passed away.

“I’m crying,” she wrote. “Jose died on April 23rd. They won’t tell me anything more though. I’m so sad …”

Just two lines of text, as if she were holding a phone stumbling over words as the tears fell. My shock quickly turned to sadness. I had been living with the hope that Jose was striding purposefully, beginning to find value in change, so it was inexplicable to me that he was … gone. At 53 years of age.

For over a week I contemplated the time we spent together. Our conversations. I even pulled out old letters.

I was reminded of his humor: “Now let me exalt the many wonderful qualities of Heritage Laundry Detergent: 1) purposely made laundry detergent contains chemicals to loosen soil/feces in your dirty underwear and other chemicals to produce the illusion that the fabric is…whiter than what it actually is.”

He could be self-deprecating: “For someone that never leaves his cell and only has one ear, I sure do come up on a lot of info, don’t I?”

Anything related to science or technology drew him like a moth to a flame. And he was fantastic at chess. We played numerous games over the years (most of which I lost!) the two games we were playing through correspondence will forever remain unfinished.

Losing one of my few precious friends is a wound to ponder, because the grief I suffer is a natural reflection of how I feel enriched by having known him. And I can find solace in this new instance of separation because I believe we are still connected by the wheel of life.

In a letter to Ines, I suggested that I wanted to write a longer eulogy to honor Jose. Maybe that is what this is. But as I consider all I’ve written, it’s likely that I already shared everything meaningful with her:

“His mind was a galaxy of Passions. He could equally comment on quasars or the price of concrete. The details mattered to him. Perhaps it was a quest of perfection. I knew him to always be ordered, tentative, respectful. He once told me that our path to friendship became possible because I didn’t ask for anything from him. I didn’t expect anything from him, but I couldn’t resist his wit, insight, deep intellect.

“In his study of physics, I think he came to believe in Masters who could visit us, guide us. I want to believe that he found his own mastery. Surely he lived long enough to develop a greater sense of appreciation of life as a whole. Some might seek to simply judge him by the death he contributed to. Others will likely say that it was impossible for him to atone for. Such hawkish nonsense could never understand the gentle man he became.

“He was my friend. I will miss him.”

I called him “Lord One Ear,” he signed his letters with, “You Know Who.”

Now I lay the King gently on its side. Rest in peace Jose.

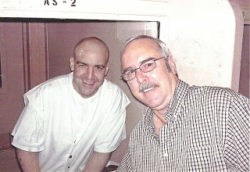

(in white, pictured with his father)

(in white, pictured with his father)

Terry Daniel McDonald 01497519

* for more information click here

1 Comment

Barbara

July 31, 2020 at 2:54 pmThank you for this beautiful and thought-provoking text!