By Jeremiah Bourgeois

I am amazed how concerned DOC (Department of Corrections) officials are for the safety of prisoners nowadays. It’s not lip service; they’re serious in Washington State. Underneath the telephones in each unit at the facility where I am confined, several phone numbers have been painted largely on the floor. PREA HOTLINE (Prison Rape Elimination Act) screams one in red, and the corresponding phone number allows you to report sexual assaults or plots. VIOLENCE REDUCTION #89 reads another in bright yellow, and hitting these three keys provides the means for reporting physical assaults or threats. Then there’s the Office of Crime Victim’s Advocacy, a recently established non-monitored private line that enables prisoners to access support if, god forbid, the PREA HOTLINE didn’t keep the rapists in check. It’s astonishing how much has changed over the past twenty years.

When I came to prison in the early nineties, there were no numbers to prevent being victimized. Frankly, it seemed to me as if the administration didn’t give a damn whether I or anyone else got our ass beat or taken so long as the whipping or raping didn’t interfere with the orderly operation of the facility. Had I bothered to report that I was sexually assaulted (thankfully I wasn’t) or that I feared being victimized (I did, indeed, have such fears back then), I would have been shunted to segregation and remain confined in a cell 23 hours a day, indefinitely, for my protection. I would have had to live under the same conditions that I would have had to endure had I committed a vicious assault rather then fled from potential assailants. In this world, perpetrators and victims met the same fate in the end: confinement in segregation. One for punishment, the other for protection. Under these circumstances, there was little to be gained by reporting anything to administrators. Instead, your best bet was to stay in general population and strive to become ruthless. Swift violence, and the threat of it, is the most effective deterrent in prison. That was the conclusion I reached when I weighed the risks and benefits of remaining in the general prison population.

He Who Didn’t Take Heed

Clallam Bay Corrections Center (CBCC) is one of two Closed Custody prisons in the State of Washington, and it is reserved for violent offenders and security threats. Prisoners convicted of first degree murder were at that time required to spend the first five years of their sentence in such a facility. When I arrived there almost twenty years ago, I was amongst the first wave of juveniles in this state that were sent to prison after being tried as if we were adults. “Scott” was part of this group too. We met in the Receiving Unit, and after our orientation was completed, both of us were transferred to the same Regular Unit. Scott was real easy to get along with, and he had a good sense of humor. Due to our similar circumstances we gravitated towards one another, and began spending hours each day playing cards together in the dayroom, clowning around like the teenagers we were. We kept each other laughing until it was time to lock up, and would start all over again the following day when we came out of our cells. That was our routine during those first few months.

Scott was 17 years old, white, and serving a 20 year sentence for a murder he committed the year before. I was 17, black, and serving life without the possibility of parole for a murder I committed when I was 14 years old. As a teenager who is new to prison, you are tested in countless ways. There are countless stratagems convicts will employ to take advantage of the naïve or unwary. If you’re black and serving time in Washington State, you are pretty much accepted by other blacks so long as you’re not a known snitch, you don’t act like a weirdo, and you aren’t serving time for something contemptible (that is, something that convicts find reprehensible such as the rape of a child). For someone like me, (I’m neither a snitch or a weirdo, and convicts found my crime to be praiseworthy) black bandits would pretty much give you a pass–that is, until you failed one of the tests that were sure to come. Once that happened, you were fair game for everything from extortion to rape.

White convicts, on the other hand, didn’t take a wait-and-see approach when it came to assessing one of their peers. Instead, a teenager like Scott had to demonstrate that he was “solid” as opposed to a “lame” before he would be accepted by his racial group. He had to prove that he was worthy to run with the whites; or rather, he had to prove that he shouldn’t get run over by them, cast aside, and left for others to have their way with (blacks included). One strike could spell disaster. One faulty move could leave a white kid without white allies: and no support would be forthcoming from blacks, for all too often crossing color lines exacerbates a problem (e.g. cause a race riot). It would be his problem, no one else’s. He would be left on his own, all alone. That was the unfortunate position in which Scott soon found himself. He made one faulty move, and wound up being brutalized.

In a nutshell, here’s how it went down: Somebody did something disrespectful to him that, under the norms of prison, merited a violent response, and Scott refused to dish out just deserts to the man who had publicly disrespected him. Sounds stupid and petty, I know. Yet that sealed his fate. He was thrown to the wolves, and the predators pounced. Shortly thereafter, he was raped in his cell—all because he was unwilling to be merciless towards someone who had violated his right to be left alone, and refused to let him live in peace. Whether his unwillingness to be ruthless was due to ethical considerations, religious views, or plain cowardice, the end result was the same: he had no one to turn to; there was no hotline for him to call. He was bent over in his cell and raped.

I learned what occurred not too long afterward. Frankly, I didn’t know what to make of it. Why didn’t he kill that son of a bitch and rapist? Why did he allow this shit to go this far? Why didn’t he nip it in the bud by fucking up the dude who had played him close in front of everybody? This was confirmation that my view of the world was on point. To survive unmolested in here I had to be ruthless. I couldn’t hesitate. I had to be merciless.

Scott and I stopped playing cards together shortly after he was raped. It just wasn’t the same. There was nothing to laugh about anymore. The dynamics of the relationship had changed.

Eventually, Scott went into protective custody, where he remained confined 23 hours a day in a cell for his safety. I remained in general population, and I became ever more proficient at protecting myself. I didn’t hesitate. I was merciless.

The next seven years of my life were defined by violence. I spent five of those years in segregation for being violent. Administrators probably thought it was all senseless violence. Yet Scott’s experience showed me that being violent made perfect sense.

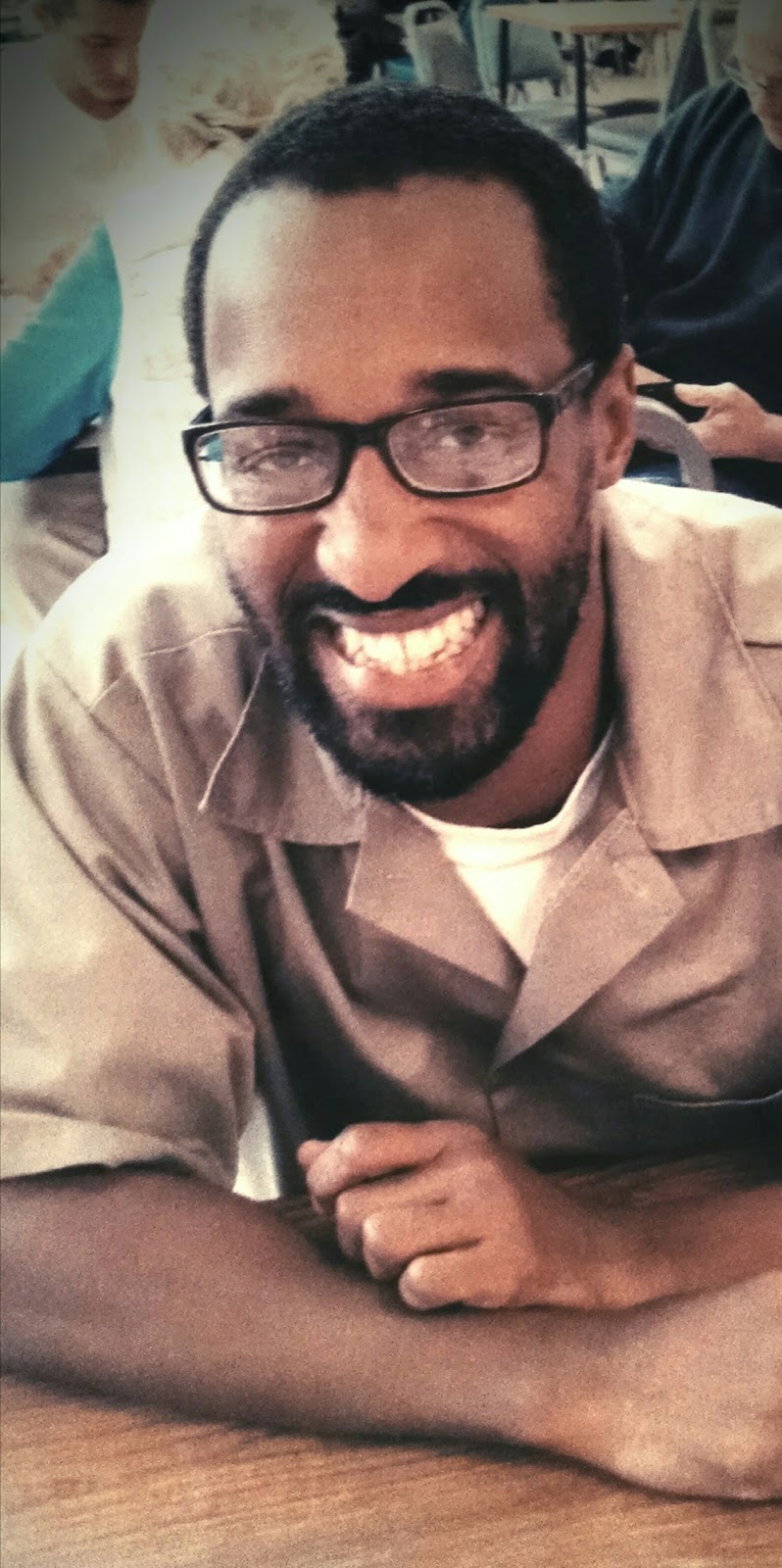

Jeremiah Bourgeois 708897

Stafford Creek Corrections Center

Unit GA L-18

191 Constantine Way

Aberdeen WA 98520

No Comments

Unknown

July 2, 2016 at 1:08 amHow are you I'm good when you get out you are going to trip they tore the hood down so much has changed but your brother and sister probably all ready told you that much love to you

Unknown

July 2, 2016 at 1:08 amI miss you jj and think about you a lot over the years I hear you are coming home soon I can't wait to see you l have much love for you and I miss you very much

Unknown

April 6, 2016 at 9:51 pmHi JJ how are you I miss you I think about you all the time I hear you gonna be coming home soon I hope so that great