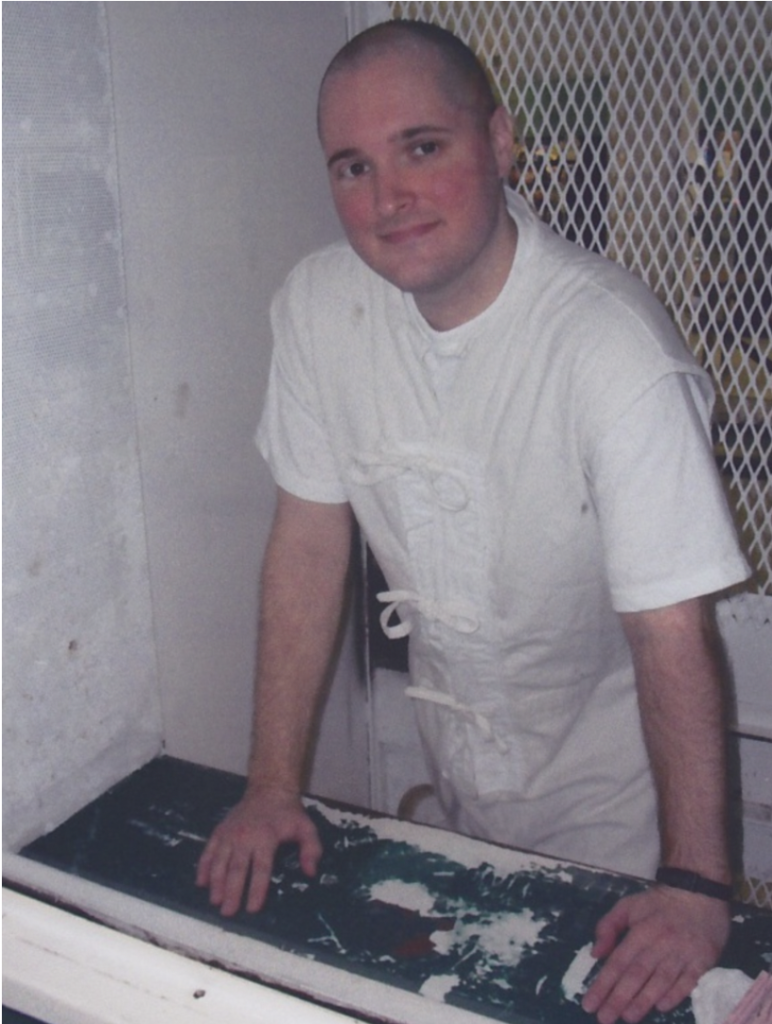

Artwork: Texas Death Machine by Arnold Prieto Jr.

On the 28th of November, nearly four weeks to the day after my arrival on Deathwatch, my attorney showed up at the Polunsky Unit bearing poetry.

This was more or less the last thing I expected James Rytting to present to me; had someone suggested his briefcase was packed solid with baby albino komodo dragons, I probably would have believed that before a poem. James had been my federal postconviction attorney for more than seven years. In all that time, I can only recall seeing him visibly display deep emotion on one occasion. Years before, he’d managed to overturn a case, thus potentially saving the life of his client Robert Fratta. Robert was remanded back to Harris County for retrial. On the morning when he was resentenced to death, James came up to the unit to visit, and he was pretty livid. The attorney who had handled the retrial was the same fraud who had bungled my own, so we had a lovely conversation where we disbarred, tarred, and feathered the poor man in increasingly ingenious ways until we both stopped midsentence and started cracking up. It was a window into a man I deeply admired, because it showed that despite his calm, affectless exterior, deep down he truly cared. This is, lamentably, not as common a characteristic as one would hope for in court-appointed attorneys in Texas.

To be an appellate lawyer handling capital cases in Texas requires an astonishing capacity for abuse. Had James decided to put the Yee-haw Republic in the rearview mirror and decamped to California, I suspect he would be batting pretty close to 1.000 on obtaining reversals for his clients. He’s pretty much the proverbial smartest-guy-in-the-room, no-matter-the-room. I was lucky to have him. As my state postconviction process was winding down in 2009, I began searching for counsel to handle my appeals in the federal courts. I absolutely did not want the attorney who had been assigned to me during my state appeals, a point that I made clear to him in a number of letters, as well as in a series of increasingly frustrated notices to the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals (TCCA). Aside from making some vague promises about my case being an “easy” one to win, I seldom heard from him and only saw him for one meaningful visit in three and a half years. During that time, I had managed to meet David Dow, a law professor at the University of Houston, and he had agreed to represent me moving forward.

On the afternoon that the TCCA denied my application for a writ of habeas corpus, Dow submitted a motion for appointment with my federal district judge, Keith Ellison. Unfortunately, my state writ attorney snuck in a motion even earlier in the day, despite the fact that he was very aware of my negative opinion of him. Once he became apprised of the situation, Judge Ellison – for reasons which must remain mysterious to we poor mortals – decided to deny the appointment of both attorneys. Several days later, when Dow was in Ellison’s court for another matter, the judge told him that he was going to instead appoint an attorney who was widely reviled by virtually everyone in the capital defense world. Dow asked him if he could have a few hours to find someone else, and the judge replied that he could have one. James Rytting was the first person Dow called. Fortunately for me, he accepted.

It weighed on him, though, as it must weigh on all of them. When he picked up my case, I was his third client. By the time my execution date was set, he’d agreed to advise or sit as secondary counsel on almost a dozen other cases. How do you say no to a plea for someone’s very existence? Past success in this realm is rewarded with bitterness, with exhaustion.

On the morning of our visit, he was understandably subdued – he almost seemed embarrassed. James Rytting did not like to lose clients to the needle. He took his duty to save my life seriously, and the setting of my date a clear sign of failure. I found myself in the strange position of feeling like I needed to cheer him up.

“I’ve written something for you,” he murmured, about an hour into our visit, his eyes downcast. I stared at him through the bullet-proof glass, trying to decide if what I was actually looking at was James Rytting acting sheepish.

“Okay…,” I responded, but in my mind I was thinking: Shit: this can’t be good. James slowly turned over a piece of paper that was sitting face down on the counter and pressed it to the glass partition:

The Dustbin of Certiorari

You’ve neared the end of the appellate case.

You’ve got the facts; you’ve got the law;

Just one conclusion a judge can draw,

On pain of being two-faced.

But a fate awaits best arguments

If a criminal claim is worthy:

To be swept, despite clear precedents,

Into the Dustbin of Certiorari.

So after you present your client’s side,

And can’t figure how you’d fail,

On hoisting toasts to eristic St. Ives,

Best stick with pints of ale.

For in the Quarters and dives Uptown,

Which surround the lofty Circuit,

The mixed drinks, they’re all watered down,

And that Fifth, it’s filled with rotgut.

My smile, hesitant at first, turned genuine midway through the second verse, and then abruptly converted into a wince when I reached the acid-bathed final two lines. James had argued in front of the 5th Circuit in New Orleans more than a dozen times, so I had no doubt that he’d had a drink or two in the French Quarter over the years. That he felt this august body’s rulings to be filled with rotgut seemed pretty perfect.

*****

I can count on the fingers of a blind butcher’s hand the number of times I’ve seen attorneys actually look happy during a legal visit at the Polunsky Unit. The simple fact is that in the fifty years since the prisoners’ rights movement flared and then burnt out, the courts have moved further and further to the right. The Rhenquist court tilted the scales so far in favor of the prosecution that obtaining a reversal in the South is an almost impossible task. The facts often don’t matter; the structural advantages given to the State are simply too overwhelming to overcome in most cases.

The system in Texas, such as it is, contains three levels of review available to provide relief to capital appellants: direct appeal to the TCCA; state habeas corpus review (which takes place before the trial court and the TCCA); and federal habeas corpus review (which takes place at three levels: the federal district court; the circuit court for Texas, Louisiana, and Mississippi, called the 5th Circuit; and the Supreme Court). The direct appeal attorney focuses purely on the record at trial and litigates any constitutional, statutory, and procedural infirmities that the appellant believes took place during those proceedings. Later steps in the process may not permit review of record claims (or may utilize a standard so difficult to reach as to practically constitute a direct bar), so this is generally a defendant’s one bite at the apple for such appeals. There is no presumption of innocence in these appeals – indeed, the appellant is presumed to be guilty and one must argue that a grave mistake has been made.

Despite the fact that the American Bar Association publishes guidelines requiring that defense teams “should consist of no fewer than two attorneys” [ABA Guideline 4.1 (a)(1)], Texas state law allows for the appointment of just a single attorney during direct appeals [Tex. Code Crim. Proc. Ann. Art. 26.052(j)(Vernon 2015)]. Of the three Texas death penalty cases I am currently aware of who reversed their convictions at the direct appeal phase (Adrian Estrada, Manuel Velez, and Christian Olsen), all three had multiple lawyers appointed to their cases; I do not believe this is a coincidence, and neither does anyone else I have consulted with on the matter. The vast majority of my peers had only one, however. In the Texas Defender Service (TDS) 2016 report “Lethally Deficient: Direct Appeals in Texas Death Penalty Cases,” this lack of personnel ranked high on the list of areas requiring reform: 68.7% (N=84) of the cases reviewed were handled by solo practitioners working in one-man offices, meaning these men and women had no one to assist them in their work or bounce ideas off of. Since there currently exists zero post-law school training systems for capital appellate counsel in Texas, these attorneys are often laboring under the weight of erroneous legal theories that are doomed to fail, and have zero contact with anyone capable of pointing this out to them. This was certainly the case with my own appeal, when the State appointed me an 85-year-old attorney from a tiny town who hadn’t handled a death penalty appeal in more than two decades, and who refused to answer any of my letters. Like my writ attorney, I met with this man on a single occasion, immediately after my trial, before I had even been sent to the Row.

The situation for the State is vastly different. The same TDS study noted that 71.4% of the cases under review hailed from urban counties where the district attorney’s office maintained an appellate division. In practice, this means that each case benefited from the attention of many attorneys, including supervisory ones with a great deal of prior experience. In my own case, Fort Bend was able to pit the experience of seven different lawyers against my lone octogenarian.

This disparity extends into the realm of finances. District attorneys are able to leverage their budgets to hire specialist counsel from the Attorney General’s Office or the Office of the State Prosecuting Attorney. This largesse is not extended to the defense, where the most common hourly rate offered to counsel in the cases under review was $100. Lawyers in the year 2000 spent on average $71.36 per hour on overheads and charged an hourly rate of $135.98 for non-capital cases, and these numbers have almost certainly swelled in the two decades since. Eleven counties in the study offered flat rates of between $3,000 and $12,500 per direct appeal, meaning that if an attorney works 500 hours on the appeal (a low-ball figure, it should be noted), counsel would be earning $6 and $25 an hour, respectively. Who would even bother with such remuneration? Almost no one.

In practice, this means that an alarmingly small group of attorneys ends up handling many of these appeals: men and women who are ideologically opposed to capital punishment and take cases regardless of the fees earned, and attorneys who are simply so bad at being lawyers that they are willing to take whatever peanuts the State throws their way. One of these attorneys in the TDS survey, during the 2014 fiscal year, managed to handle eight capital murder trials, 66 adult felony trials, five adult misdemeanor cases, and eight adult felony appeals, for a total of 1,030 hours – 10.3 productive hours per day, without breaks. He also managed to cram in 13 felony case dispositions, a bond forfeiture proceeding, a competency hearing, and billed 51 hours for a capital direct appeal.

The results are about what you’d expect. In direct appeals, appellants are deemed to have waived an issue on appeal if each argument does not encompass a solitary issue or is not supported by citations to the trial record and legal authority. This forfeiture happens in one or more appellate issues in about a third of cases. Understand what this means: in one third of all direct appeals prisoners are losing the ability to appeal one or more issues, not because they lack merit, but rather because they are not formatted in the manner demanded by the TCCA. Once waived, they may be procedurally off-limits for the rest of that inmate’s appellate life. The TDS study also noted that half of all briefs contained text that was copied and pasted from other direct appeals; this included copying errors (such as incorrect issue labelling, erroneous page numbering, and incorrect citations to the relevant statute) in a whopping 12% of all direct appeals. When this sort of thing happens in, say, New York or Oregon, the offending lawyer would be sanctioned for plagiarism. In Columbus Bar Association v Farmer, the Ohio Supreme Court suspended an attorney’s license for failing to independently analyze that client’s unique legal options. This has never happened in Texas – not once – so copying and pasting is frighteningly common. Try to imagine what it would feel like to wait months for one’s attorney to mail you a court filing – a filing meant to save your life – only to receive it and learn that it had someone else’s name inside the text, or facts that relate to a completely different case. This happens. I’ve known men who died for this.

The situation actually gets worse when one moves into the second layer of appellate review, state postconviction appeals, sometimes referred as “state habeas corpus” appeals. In theory, these proceedings are designed to give an important second look at what happened (or didn’t happen) at trial. This may include ineffective assistance of counsel (IAC) claims, Brady violations (i.e. improperly withheld evidence known to the State but not turned over to the defense as required by law), recanted witness testimony, or newly discovered evidence. Prior to 1995, Texas didn’t even bother appointing State writ lawyers to represent indigent death-sentenced inmates. After the 5th Circuit Court concluded in Mata v Johnson that the TCCA had not fulfilled its statutory duty to develop standards of competency for postconviction review, an ad hoc system was created by the legislature that shifted responsibility for such appointments away from the all-Republican TCCA and towards eleven different Administrative Judicial Regions, in an attempt to deflect blame from GOP-elected judges. They then failed to fund the project, providing sufficient monies to cover only 180 of the 414 inmates needing counsel. Since they were capping fees at $7,500 at $100 per hour, it is perhaps not so surprising that of the roughly 3,000 letters the TCCA mailed to members of the Texas Criminal Defense Lawyers Association, fewer than 400 actually responded in some fashion. Interestingly, the TCCA’s Presiding Judge Michael McCormick specifically mentioned that any attorneys seeking appointment didn’t require any special training. Instead, he simply said that they were interested in “people we feel comfortable with”. Since all of these judges ran on openly pro-prosecution and pro-capital punishment platforms, one can’t help but wonder if the “comfortable people” bit was code for attorneys who were inexperienced and who weren’t going to fight them terribly hard. If this was the goal, the plan worked amazingly well.

If a state writ application is handled by a truly interested and well-funded defense team, it might contain affidavits from experts or witnesses about evidence that should have been presented at trial, or that argue the evidence shown to the jury was in some way tainted. Such appeals often point out the ways that trial counsel failed to investigate mitigating evidence, or that they simply misunderstood some basic aspect of the defendant’s case that made their entire defense strategy ineffective. Increasingly, these appeals often present materials that were hidden by prosecutors but which managed to later escape into the public sphere.

The goal of this process is to establish an understanding of fact: what happened at trial, what didn’t happen, what, if anything, should have happened. The condemned will file a petition, the State will respond to this, and then the trial judge will write a “findings of fact and conclusions of law”. This is a set of recommendations that is sent to the nine judges of the TCCA about whether an appellant should receive or be denied relief. There may be hundreds of these factual findings in a capital case; there may be documents and affidavits and reports. In virtually every case about which I am aware, the TCCA has sided with the trial judge’s recommendations. I can think of only three cases out of several hundred that I have studied over the years where the TCCA ruled against a trial court’s recommendations: those of Eric Cathey, Bobby Moore, and Erica Sheppard. In all of these cases, the trial judge recommended granting relief, only to have the TCCA deny those claims, a point which is in itself quite suspicious, and which I think says quite a lot about the judicial tendencies of that court. For reasons that will be discussed shortly, the federal courts must give great deference to the facts of the state court, so it is not an understatement to say this “findings of fact” document is the most important set of papers in the life of a capital defendant.

A recent study by Jordan Steiker, James Marcus, and Thea Posel drops a smart bomb onto the State’s pretentions of fairness in these appeals. In “The Problem of ‘Rubber-Stamping’ in State Capital Habeas Proceedings: A Harris County Case Study”, these three University of Texas law school professors analyzed 191 state writ appeals, and showed that in almost every case, judges typically signed off verbatim to the prosecution’s proposed findings of fact, sometimes mere days after these had been filed. Of the 21,275 findings of fact proposed by the Harris County District Attorney’s Office, a staggering 20,261 were adopted word for word, a rate of 95%. Forty judges in the county have adopted every single findings of fact ever proposed by the State: not once have these judges ever agreed on a single contested fact provided by the defense in any of the cases they have adjudicated. Eight of these judges have accepted the State’s version of events 100% of the time since 1995. In 167 of the 191 cases in the study, the judges simply signed the State’s proposed facts document without even changing the heading. Understand what this means: in 87.4% of all Harris County death penalty habeas reviews, judges essentially let prosecutors write their opinions for them. Once these conclusions have been signed off on, the all-Republican TCCA affirms them, denies relief, and sends the appellant off into the federal courts, all without having given a single fact genuine review.

There was a time when this would not have been the end of the world. In the not-too-distant past, the federal judiciary had wide discretion to reverse obviously rigged state court processes, but those days ended in 1996 when Congress passed the Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act (AEDPA). Under AEDPA, only “unreasonable” rulings can be overturned, not just erroneous or questionable ones. In practice, this means that as long as a state court ruling adheres to some sort of internal logic that is consistent with state law, the federal courts cannot overturn it, even if they’d like to. There’s a special sort of gut punch reserved for capital appellants whose claims are meritorious yet insufficient to produce a reversal. If one is lucky enough to be placed into a federal court overseen by a Democratic-nominated judge, one will on occasion find in one’s ruling words similar to: “If it weren’t for circuit court precedent, I would overturn on [such-and-such] issue.” I had one of these declarations in my own denial, and it essentially meant: “If you’d committed your crime one state to the west, you would have survived. Sorry.” Because the circuit courts in the South are dominated by judges who are on record as being strong supporters of the death penalty, this ultimately means that one can proceed through all three phases of one’s appeal and never once land in a court where the arbiter even pretends to have doubts about the fairness of the trial court process. I know; I experienced this myself.

*****

I began to become acquainted with the freakishly politicized nature of death penalty appeals soon after my arrival on the Row. As I watched case after case fly through the process, I began to realize that it was virtually unheard of to gain a reversal on certain issues, and that the likelihood of such had absolutely nothing to do with the merits of one’s claims, but rather on the structural limits placed on appellants. I had all but pinned my hopes for survival on my IAC claim, given everything that my trial attorney did not do correctly. Like the public, I badly misunderstood the difficulty of prevailing on such claims. Texas has an unfortunate history of assigning capital cases to lawyers with zero experience in the field. We’ve had lawyers show up to court drunk, ones who have been caught sleeping during key moments, or with extensive disciplinary histories. Despite this, I can think of only one case overturned on an IAC claim the entire eleven years I spent on the Row. The reason for this is Strickland v Washington, which all but bulletproofs cases against error.

Strickland has two prongs. The first requires that the appellant demonstrates that one’s attorney fell below an “objective standard of reasonableness” as measured by “prevailing professional norms”. Courts are required to apply a “strong presumption” that one’s attorney conducted him or herself within a “wide range” of reasonable professional assistance, according to Harrington v Richter. In practice, this means that as long as one’s trial counsel can claim to have been making their mistakes under the guidance of some sort of “trial strategy”, their behavior will be permitted and considered off-limits to the federal judiciary. The standard for what constitutes strategy is remarkably low; in my own case, after it was apparent that I had become aware of the various lies my trial attorney told to me and my father, he swapped sides, assisted the prosecution, and essentially said that his entire strategy was destroyed by the fact that I had no “conscious” [sic]. The second prong of Strickland is even more difficult to reach, in that one must prove that there was a “reasonable probability that, but for counsel’s unprofessional errors, the result of the proceeding would have been different”. Of course, there is really only one way to know this, which is to contact the twelve jurors who sat the trial, lay out the new information to them, and then ask them if this would have altered their verdict. This is never done. If one submits affidavits proving this very fact, they are ignored, and hearings on such subjects are almost impossible to obtain. Instead, judges hypothesize why such errors wouldn’t have changed the verdict, and then deny relief. This takes place in almost every case I’ve ever studied where the first prong of Strickland has been reached – which in and of itself almost never happens.

In my first year on the Row, they killed five men who had very credible IAC claims, claims that were as good as my own, if not better. Each time another man was killed, it sent me deeper into a tailspin, further degrading my hopes that the law might prove to be my friend. It’s hard to say exactly when I gave up on this approach; it was a rough waltz into a quiet acceptance of ultimate annihilation. From time to time I’d glance around, hoping to catch sight of some other form of deus ex machina, some other piece of flotsam in an endless expanse of turbulent water. Most of my friends ended up chasing the comforting mirage of religion, but this didn’t work for me. Indeed, my experiences on the Row all but murdered my beliefs in a theistic deity. For the most part, I sort of bought into the existentialist’s pursuit of subjective meaning, deciding that if I was doomed, I wanted to go to my death marginally less stupid than when I had been arrested. Education became my polestar, and I began figuring out the difficult riddle of how to attend college classes via correspondence courses. I knew I was sinking, but I resolved to myself that I was going to sink with dignity. I’m not sure how successful I was at this, but the attempt was all I felt I had left.

*****

I became aware of another option in the months leading up to the successful clemency bid of Kenneth Foster. In the days leading up to “Outlaw’s” execution, word had made the rounds that his defense was going to be attempting a novel clemency argument, but I hadn’t the slightest idea what this meant. As life rafts go, I could perhaps be forgiven for having overlooked something so miniscule. In theory, the executive clemency process is supposed to function as a final safeguard against unfair punishments, particularly in cases where the factual landscape is atypical. The concept of clemency goes back to English common law, and was designed to give the State a final opportunity to say: Look, we could kill this person – we have the legal right to do so – but there’s just something about this particular case that suggests an execution isn’t entirely right, it isn’t completely just.

The reason that I hadn’t bothered to study the clemency process up to that point is that such requests are almost always denied, and I had been told by several writ writers and attorneys that clemency didn’t really exist in Texas. Between 1973 and 2013, there were only 392 death penalty commutations granted in the entire nation, though this number is a tad misleading because 163 of them took place at the same time, when Governor George Ryan granted clemency to everyone on Illinois’ Death Row after a series of scandals came to light regarding the Chicago Police Department. The numbers for Texas are about what you’d expect: despite having the most active capital punishment system in the western world, Texas had only granted clemency once since 1976, prior to Foster’s attempt. Henry Lee Lucas was sentenced to death in 1979 after confessing to the murder of a young woman. It was later discovered that Lucas had something of a penchant for fabricating confessions – to the tune of several hundred crimes spanning many years. It soon became apparent that Lucas had been in Florida at the time of the murder for which he was condemned, so Governor Bush commuted his sentence to life in prison in 1998.

The second ended up being Kenneth Foster. In Outlaw’s case, he had been the getaway driver for what he believed to be an attempted robbery; when his co-defendant committed a murder instead, Foster was sentenced to die under Texas’ Law of Parties (LoP). Although Governor Perry never mentioned the LoP statute in his commutation order, most of the attorneys I spoke with seemed to believe Foster’s status as the non-triggerman had been the underlying driver. So, too, was the fact that Foster’s attorney, Keith Hampton, had utilized an almost entirely religious argument to justify the State granting clemency. Since Foster’s partner in crime had already been executed, Hampton argued that killing his client would take the world back to a time before Moses – it would, in fact, amount to two eyes for an eye, two teeth for a tooth. No one had ever attempted anything like this before. Most everyone I spoke to in the legal community thought Hampton was insane. I thought it was genius, because it spoke to his understanding of just how conservative Texas politics had become. When Foster’s bid turned out to be successful, it shifted at least some of my focus away from the law and towards the clemency system and the peculiar nature of the people tasked with deciding these matters. Any system, I reasoned, that cast “an eye for an eye” as being radically progressive was bound to have some weird holes in it that I could utilize.

For years I slogged my way through journal articles, news reports, and, once I figured out how to use the Texas Open Records Act, the Texas Board of Pardons and Paroles’ Self-Evaluation Reports written for the legislature every two years. I began to form a sort of theory of Texas clemency, starting with the fact that it seemed increasingly apparent that attorneys were filing on the wrong issues, or filing them in a way that was guaranteed to fail. This wasn’t entirely their fault, as in most capital jurisdictions in America, the clemency process is treated as seriously as a court process, and legal arguments are given consideration. This is absolutely not the case in Texas. Instead of petitions being reviewed by judges steeped in legal tradition, the seven members of the Texas Board of Pardons and Paroles are responsible for receiving clemency petitions and then passing on a recommendation to the Governor. If a majority of the Board recommends clemency, the Governor may choose to accept or deny the recommendation. If the Board does not recommend mercy, however, the Governor lacks statutory power to commute the sentence, the result of a 1936 constitutional amendment created after the public became concerned that the executive might be bribed to issue pardons unilaterally. The members are all appointed by the Governor and serve staggered six-year terms; they are all selected because they are ideologically in line with the Governor’s stances on criminal justice issues, including the death penalty. In this way does the Governor insulate himself from the charge of being devoid of mercy or compassion: by installing uber-conservative members to the Board, he is assured that very rarely will he be actually presented with a positive recommendation, meaning he is free to mimic Pontius Pilate and claim that the state’s high record of executions is out of his hands.

The members of the Board are not lawyers. They are not required by statute to conduct any specific procedural review of the cases before them. In fact, according to 37 Tex. Admin. Code § 143.42(g), all condemned prisoners must persuade the Board to recommend granting clemency without asking members to resolve technical considerations of law. In all of my years preparing my own clemency bid, I wrote to dozens of practicing attorneys all across the state, and only a handful seemed to be aware of this and the potential implications of this statute. Trained over the course of many years to write legal briefs, when it came to clemency petitions, lawyers were generally just retooling arguments they had deployed earlier in the appellate process, complete with explanations about how and why various courts had gotten everything wrong. From the Self-Evaluation Reports, I knew this to be a strategy doomed to failure. According to former Board member, LaFayette Collins, “You don’t vote guilt or innocence. You don’t retry the trial. You just make sure everything is in order, and there are no glaring errors… We get all kinds of reports, but we don’t have the mechanisms to vet them.” Paddy Burwell painted an even darker picture, saying that on numerous cases he received subtle pressure from other members to vote against clemency: “I don’t think they care whether a person is guilty or not guilty.” Federal judge Sam Spark wrote that the current Board set-up seemed to be designed “more to protect the secrecy and autonomy of the system rather than carrying out an efficient, legally sound system”, adding that “none of the members” of the Board fully read the clemency materials presented to them.

The results of this approach were universally and catastrophically awful. A complete litany of all of the petitions that were denied in part because Board members refused to see it as their duty to independently review fact, evidence, or circumstances related to their decisions would cover thousands of pages. But you don’t have to travel very deep into this world before you find some cases that burrow under your skin and start to fester.

Cameron Todd Willingham was convicted for a fire that killed his three children after the State used outdated and outright bogus arson “science”, the testimony of a jailhouse snitch who later recanted, and the expert opinion of a psychologist later expelled from the American Psychiatric Association. Willingham was executed on the 17th of February 2004, the Board and Governor Perry claiming their decision was “based on the facts of the case”, facts which were shown to be anything but, in a petition it’s not clear was ever read by anyone.

The evidence against David Spence consisted of now disproven forensic odontological (i.e., bite mark) evidence, plus the testimony of several jailhouse snitches. It was later revealed that Spence wasn’t even in jail when one of the snitches claimed he had confessed. Others later admitted that police provided them with crime scene photographs, witness statements, and autopsy photos, so they could better invent their stories; some were even offered cigarettes, television privileges, and booze, in exchange for their lies. Spence was executed on the 3rd of April 1997, after a mouthpiece for Governor Bush claimed the verdict was fair and the sentence justified. The Board said not one word publicly.

Humberto Leal Garcia was a Mexican national denied his rights under Article 36 of the Vienna Convention, which guaranteed him access to consular officials once arrested. Despite calls from the International Court of Justice, President Obama, and George W. Bush, the Board denied him clemency, and he was executed on the 7th of July 2011.

The federal courts found that Marvin Lee Wilson had an IQ of 61, deep within the commonly accepted range for mental retardation, along with “significant limitations in all three areas of adaptive functioning”. He was denied relief in the courts due to limits placed on the federal courts’ ability to review his claims on the merits, and his clemency petition attempted to revive these claims. The Board rejected these arguments without comment, and he was killed on the 7th of August 2012.

James Blake Colburn, Larry Keith Robison, and Robert Vannoy Black, Jr. all submitted clemency petitions detailing extensive mental health concerns, including schizophrenia in the first two and Vietnam War-inspired PTSD in the last. Despite documented histories of time spent in mental institutions, all three men had their petitions denied without comment, and all were killed.

All of these men were worthy of mercy; all had valid petitions showing clear errors in the judicial process that in virtually every other state in the nation should have produced a different outcome. The fact that most of these men didn’t manage to garner a single vote in favor of clemency taught me that the content of a clemency petition is largely irrelevant, so long as the rhetoric used to convey that content did not follow a very particular format or utilize a specific idiom. Lawyers needed to write their petitions, I decided, as if they were speaking to a group of evangelicals gathered for a Bible study, because they were. This seemed so obvious to me that I couldn’t understand why more attorneys didn’t attempt to wrap their clemency arguments in the vestments of religion.

One reason that this was perhaps not as obvious as it might have been is that obtaining statistics and information about clemency is much more difficult than it should be. Unlike with federal court filings, which are published on www.pacer.gov for anyone with a credit card to view, there didn’t appear to be a state office that made submitted clemency petitions available for public view. When I initially mailed the Clemency Division of the Texas Board of Pardons and Paroles in early 2008, I was told that I needed to contact the lawyers responsible for the filings directly if I wanted to read the actual petitions. Since there is no right to counsel in capital clemency proceedings, I learned very quickly that most of the men who had been executed in recent years hadn’t even bothered to file a petition at all. One lawyer told me that during the 90s and early aughts, this number might have amounted to roughly 85%. The percentage filing petitions ticked up a bit in 2008 after the Supreme Court held in Harbison v Bell that federal law permitted (but did not require) “federally appointed counsel to represent their clients in state clemency proceedings and entitled them to compensation for that representation”. Since they were now guaranteed payment, more lawyers filed petitions – shock, I know. But since attorneys had by and large given up on the trial-and-error process of discovering what might work, they continued to file the same petitions steeped in legalese, and got the same dead clients as a result.

What would work? Outside of Keith Hampton, nobody seemed to have any new ideas – they had, in fact, completely consigned clemency to the realms of the mythical. It seemed to me, however, that nobody had ever really tried treating the process in the same way that a regular prisoner treated parole. There were a few tantalizing comments hidden within the Self-Evaluation Reports that at least some of the Board members had on occasion been looking for signs of rehabilitation in the men facing execution. What would happen if someone delivered a gigantic stack of certificates and diplomas, evidence of a genuine attempt to better themselves? People dismissed my early comments on this, but it was for the most part an untested hypothesis, one that seemed obviously full of potential to me, especially since it was my intention to engage in this sort of behavior anyways, regardless of the results. What if one combined this sort of effort with a perfect disciplinary record, and then added the consideration that one was not the actual shooter in one’s case, and that the shooter had never even been considered for the death penalty? Would that open the door enough to put my family’s opposition to capital punishment into play? Many things about the way my case was prosecuted bothered my dad, but the fact that the State claimed to speak for my mother and brother over his own wishes gnawed at him the most. Was there a place in this so-called Victims’ Rights Paradise for victims that preferred mercy over vengeance? I thought there might be, given the theological beliefs of each of the members of the Board.

None of my attorneys really believed in my theory. In one of his first emails to my father after my execution date had been set, David Dow put the matter succinctly: “Clemency is not an option in this case.” Both he and James Rytting had largely tolerated my idealistic wanderings on the subject, thinking, I guess, that there was no harm in it. Despite their misgivings, both were committed to submitting a petition centered on my beliefs about the Board, to their credit. I had long had hopes of convincing Keith Hampton to help, but as the last days of November petered out, he was still noncommittal. Both George W. Bush and Rick Perry had granted clemency a single time during their time as Governor. I was intending to be Abbott’s first, but it’s safe to say that outside of my father, stepmother, and a few close friends I’d been corresponding with for years, hardly anyone felt I had a chance of living beyond the 22nd of February 2018.

Inmates in general, and condemned prisoners in particular, don’t receive a ton of moral support or encouragement in their daily lives, so just having a few people around who believe in your goals is amazingly important for keeping one’s motivational gas tank topped off, and for avoiding the ever-present tendrils of despair that are always trying to latch onto you. Somehow, despite all of the conversations I’d had over the years with friends with execution dates, I’d never contacted a phenomenon regarding pen-pals that I was to find was pretty common amongst the near-terminal. During those first few weeks of my time on Deathwatch, I wrote everyone I was currently corresponding with, explaining to them the situation and how I intended to handle every aspect of my death, including a description of how much time I intended to spend on correspondence. I honestly expected everyone to be understanding and supportive. By that point, I felt I had weeded out just about everyone who was going to be unlikely to be able to handle the pressures of the moment. I didn’t really need most of my friends to do much of anything during this time, other than remaining calm and tough. But I did expect them to be capable of managing their own stress and not pass this along to me. Most importantly, I expected them to at least ask what could be done, to in some way express presence and solidarity. This was, I felt, the bare minimum that genuine human beings need to be able to broadcast to each other during such moments.

This was apparently too much to ask of some people, though. I never heard from a handful after I received my date. As the weeks went by, I went through a sort of impatient confusion about this cohort, wondering what was taking these people so long to write me back. By late December, I had come to the realization that they simply weren’t going to write at all, and that these relationships hadn’t actually been composed of friends in the first place. The analogy I kept coming back to was that of me dying of cancer. Had I been in the hospital, would these people have shown up to say goodbye? It became pretty clear that the answer was no.

It took me awhile to bring this subject up with the other men on Deathwatch. I think I figured this would reflect negatively on me, like there was something wrong with me for not having known that some of these people were flakey. Once we started talking about it, however, it became clear that the magical disappearing friend act was fairly common. Everyone but Batman had experienced this to some degree, and I think he was immune only because by that point he’d just about driven everyone away already. I also learned that I was the only ogre in the group, in that I seemed to be the only person who actually intended to completely sever ties with these people, should I survive and they decide to eventually reappear. Everyone else seemed ready to forgive all, to recognize that some people just didn’t have the strength needed to deal with an execution. I did understand their perspective, and I think it says quite a lot about how the proximity to death had made men like Rod, Castillo, and Rayford even more kind, mature, and human. I think, on some level, they all believed that they were going to be standing in front of the Mercy Seat in the near future, and they were trying to show that they, too, were capable of grace. My experiences and beliefs were distinct, however, and I perceived my Death Row years differently. Without a deity to rely on to make the world more just, we humanists have only ourselves to count on for improvements. And that means that there are basically two kinds of people: those who see an evil and turn away, and those who roll up their sleeves and get to work. Rod’s years on the Row had made him a better Christian; mine had turned me into someone committed to the process of making the concept of the prison more effective, to try to nudge things back towards the original idea of actually reforming prisoners, instead of destroying them. Whether this took the form of filing lawsuits, writing essays, or involving myself in various movements of solidarity behind the walls, it had made me into that second kind of person, and I have very little time or patience for the former. I resolved that if I survived my brush with death, I would never again correspond with people who didn’t fit the activist profile, to ignore potential correspondents who weren’t writing for the expressed reason of wanting to change the system in some way. I figured this decision would eventually sever me from the normal world of pen-pals. It felt right, though, and still does. “I’m watching a world burn down,” I remember telling Rod. “I don’t have time for chit-chat.”

“That’s going to get awful lonely, Master Quijote,” he responded.

“You’ll be right there with me, Rocinante.”

“Oh, that’s right, make the Mexican the fucking horse.”

“Those windmills will never know what hit them.”

As with so many things, he turned out to be right about the loneliness thing, but I don’t currently have any regrets. I may have a different answer for you in another decade, though.

Fortunately, I did have several friends who handled themselves magnificently. I created a website in 2007, called Minutes Before Six. For five years, this principally published my own essays, though on occasion we would feature some guest writers. In 2012, we vastly expanded the list of contributors, and began posting new content every week. This required a similar expansion of staff managing the site; eventually we incorporated under 501(c)(3), with Dina Milito as Executive Director. We knew that a huge media push would be needed if my clemency petition was going to have any chance of success, and Dina began organizing things with many of the site’s volunteers, contributors, and readers months ahead of my move to Deathwatch. We knew the readership would be incredibly important in catalyzing a movement in the social media world; what we didn’t know was the precise moment to set the boulder rolling down the mountainside, aimed at the Capitol. I couldn’t know whether that landslide would matter, but it definitely made my last months easier to bear, just knowing that there were people out in the freeworld plotting and planning for my benefit. It made me feel like I was fighting, whereas everyone else just seemed to be merely dying.

I was not unique in perceiving things in this way. Although we never really spoke about it directly, almost from the beginning of my arrival to the section, the other cons had perceived my date a little differently from their own, as if it wasn’t quite as real as theirs were. I felt absolutely rotten about this, because I didn’t have any more value as a human being than anyone else. I’d simply made different choices during my time on the Row, and these choices were now conferring an advantage. It’s easy to rattle off platitudes about how fortune favors the prepared mind, but quite another thing when you are surrounded by people who are mere weeks away from being tied down to a gurney and pumped full of poison. There were times when the differences between my situation and that of everyone else made conversation impossible, or at least highly truncated. While I was having multiple legal visits every week, some guys weren’t even getting letters from their lawyers. I was really proud of the operation I had put together, but ashamed of the privileges I enjoyed that made this possible, and outraged that I might be the only man in the section with even a tiny chance of being alive six months hence.

I felt this complex of emotions most strongly when I interacted with Juan Castillo. Years before, he’d had an exceptional attorney from California offer up his services for free, but Juan decided to go with his court-appointed attorney from San Antonio, thinking that a local guy might be able to conduct a better investigation. He did not know that this was a terrible decision, that his attorney had a habit of filing anemic briefs and of finally abandoning his clients at the end of their appeals process. Despite this, Juan was always waiting at his door when he saw me returning from a legal visit – was always, in fact, hoping I’d heard some good news.

“Long day?” Castillo asked me upon my return from my first post-date visit with James Rytting.

“Yeah. Lawyer, you know?”

He knew.

“Mine thinks I’ve lost it. I keep telling them that I’m going to see 2018. I don’t know how, but I will. I know that sounds crazy,” he added, his voice dropping almost to a whisper.

I couldn’t help but glance at the calendar, zeroing in on the 14th of December, his execution date. Seventeen days, I counted off, thinking how hope can be twisted into a form of incurable haemophilia here in this place, where men become numbers, become gone too soon. Not really knowing what to say to him in response, I watched the evening sunlight pass effortlessly through barbed wires, fences, and bars and splash against the walls of the picket like radioactive cherry-flavored jello. I thought about craziness, and how after so many years in prison I no longer had any confidence that I knew how to identify lunacy, even if it was staring me in the face.

3 Comments

Deborah Allen

February 7, 2024 at 4:13 amThomas,

I totally understand your feelings about the “friends” you didn’t hear from after your date was announced. My son took his own life in 2019 and most of the people who should have supported me disappeared. Apparently, *they* couldn’t handle it. I’m acutely aware that it’s two very different situations, I just wanted you to know that I understand the abandonment, at least that’s how it felt to me.

I love your writing. These articles are entertaining me and lifting my spirits on the many sleepless nights I have. That, I thank you for.

Dividing by Zero - Part Five - Minutes Before Six

July 16, 2023 at 6:00 pm[…] To read Part Four click here […]

LD

May 3, 2023 at 5:38 pmVery powerful writing.

Extremely thought provoking.

I’m staring out in space actually.