By Thomas Bartlett Whitaker

To My Brothers on the Row,

Greetings from the loony bin. By the time you read this, it will have been a year since I departed from our infamous fraternity. I’ve tried to send some words to a number of you, but have thus far been blocked by the stalwart defenders of unfreedom in the Polunsky Palace’s mailroom. I’ve decided to try a strategy here recommended by the dandelion, tossing these thoughts out into the wind in the hopes that a friendly breeze or two might direct them where they need to go. Stranger things have happened. Dandelions abound.

I think of you often. The past twelve months have been very educational for me. Since this is my first trip to prison, I seldom had anything to add to our conversations when many of you spoke about what life was like on the other units, in other circumstances outside of a struggle for continued existence. I confess I never quite believed some of you when you commented that Death Row was “adult day care” compared to “real” prison. How on earth could living in a maximum security long-term isolation wing whilst waiting on an unruly pack of rednecks to murder me be considered “easy” time? How could Polunsky be considered a “clean farm”, when all I had to do to view the most disgusting examples of filth was to pick any direction at random and open my eyes? In secret, I always assumed that you were engaged in a sort of mental contortionism designed to trick yourselves into some sort of passive acquiescence of your current existence. Sure, this sucks, but I’ve been through worse, I saw you repeating to yourselves. I truly didn’t believe it could get worse. Damn fool I is, to paraphrase some lingo taught by JR and DBO. In no particular order, here are some of the things I’ve learned over the past twelve months, things I wish I had known when I was amongst you. Some of this might have bled a teensy bit of the pressure I was feeling – might have helped me to pick my battles in a more intelligent manner, instead of getting caught up in nonsenses that were in all actuality truly irrelevant.

Since we parted ways, I’ve witnessed admin-seg wings at the Byrd, Michael, and Coffield Units. As shocking as this may seem, Polunsky is unquestionably the most sanitary of the facilities I’ve been forced to live in. Sure, it can be nauseating – especially the showers. But “nauseating” is a relative descriptor, and I’ve learned that the spectrum of nauseatingness is far more vast than I had ever previously understood. At the Byrd Unit, everyone who passes through that facility is aware that their stay is a temporary one. For many of us, the number of hours or days we will have to survive in a given cell is irrelevant: so long as we have to exist in that space for even one minute, we want it to be as clean as possible. Not everyone feels this way, obviously. For many, the realization that they will be sent on chain after meeting with Classification and Sociology means that they aren’t going to bother with cleaning up after themselves. For some, the mere fact that they are in prison and aren’t getting assigned to an ID unit near their families or homeboys means that they are going to take out their ire on the cell itself, and, since you are the poor shmuck that got assigned to that cell after they departed, on you as well. It’s apparently become a thing in the TDCJ to spray liquefied fecal matter into the air ducts or light fixtures, as I have unfortunately borne witness to this foul trend in numerous cells. Nothing quite encapsulates the lack of solidarity found in our modern prisoners quite like a few pounds of rotting shit being left behind in an area you can’t reach to clean.

Here at Michael, these cells are destroyed. Holes punched in the walls, windows cracked or painted over from the outside, foundation warped into oddly mesmerizing patterns: this is considered normal. I initially thought that they had painted the ceilings on the runs black, until I realized that what I was looking at was three decades of soot from countless conflagrations. Fires are something of a habit here, a point I mentioned in my August 2018 update (which, if the aforementioned friendly breezes are feeling particularly generous, might end up printing out and delivering to you as well, as it contains some information on some legal chicanery engaged in by our hick political class that you might want to be aware of). Mind, I’m not talking about a few old JPAYs tossed into a pile and lit up. Rather, I’m talking about huge mountains of newspaper, towels, blankets, and jackets rolled up in a sheet and then tossed out onto the run aflame. I’m talking about entire mattresses converted into bonfires. This building lacks the exhaust vents that were installed at Polunsky, so the smoke really has nowhere to go besides one’s lungs. On New Year’s Eve, half the pod burned a sizable portion of the contents of their cells at midnight. My neighbor – an anarchist with an unusual degree of devotion to his craft – managed to save up a dozen asthma inhalers. Where he got them, I have no idea and don’t want to know. Turns out, if you wrap up one of these in a sock stuffed with paper and then torch the thing, the metal cartridge inside the inhaler will explode after about sixty seconds. When I say explode, I do not mean some sort of weak popping sound: I mean the device goes off like a gunshot. The shrapnel from one of these detonations actually deflected off my door with a pinging noise so discernible that I heard it through my earplugs. These are particularly effective when a decoy has been lit, drawing the attention of the officers. Because they do not want Huntsville to know about the frequency of these disturbances, the COs are under orders not to use the fire extinguishers, the use of which must be logged. Instead, they simply keep red buckets by the picket. Once a fire starts, they walk over to the fire hose installed inside the picket’s exterior wall, fill up the bucket, and then proceed to douse the flames. My neighbor managed to time the lighting of his grenade so that it exploded right as an officer was nearing the top of the stairs. The poor guy shrieked, dropped his bucket, and dove down the run towards 80 cell. I initially couldn’t understand the exact nature of his curses, because everyone else was laughing so loud. To my surprise, I began to hear him joining in, until he slouched along the run, hugging the wall, and dug around in the still-smouldering debris with his boot.

“Oh, you fuckers,” he panted, trying to control his laughter. “Okay, you sumbitches. Do us ‘nother one, but let me take my ass over by the shower first.” His whoops joined those of the inmates during subsequent detonations. I guess that was … nice? I mean, it’s better than what the response would have been at Polunsky, though it also kind of points to the fact that in this asylum, many of the inmates wear grey uniforms.

Still, compared to Coffield Unit, Michael is what Heaven would look like if St. Peter only admitted meth-addicted housecleaners. Coffield is one of those facilities built midway through the last century, when prison architecture was by design somewhat more porous than more recent iterations. The cellblocks there are four stories, all of which are fronted by floor to ceiling windows, essentially converting the entire building into a solarium. (I nearly wrote “furnace” there, which, while technically inaccurate, feels far more apposite.) To ameliorate the temperatures – which can reach into the 140°F range in terms of heat index values – many of these windows swivel out on hinges. Those that don’t tend to get shattered by projectiles around mid-April, or bashed out by the officers themselves with batons. I’m pretty certain we are singlehandedly supporting the glass economy of East Texas at the Coffield Unit. While we certainly appreciate the air circulation this occasionally allows, it also rolls out the welcome mat for pretty much every sort of creature indigenous to this part of the state. Sure, I already knew about the roaches and ants and spiders; Polunsky educated me on all of that within a few weeks of my arrival. Michael taught me both the joys and frustrations of living in close proximity to about six million mice, as well as giving me ample opportunity to empirically calculate exactly how many Ramen soups a battalion of field mice can chew through during the course of a single fifteen-minute nap. I’ve learned to train the ones that currently live inside my doorframe. Look at the big brain on me, I tell myself when I see them parade in around 8pm and line themselves up at a specific point near my door, all sitting there on their haunches, looking as cute as something out of a Disney cartoon, where I feed them of an evening. Of course, I’m certain that on some level they are squeaking something similar to themselves: look at the big brains on us, the way we’ve trained our human to feed us when we sit at this exact spot. As is often the case, perspective is everything. I very nearly titled this essay “Of Mice and Men…. but Mostly Mice.”

Coffield extended my behind-the-bars safari expedition to cover semi-feral cats and several species of birds. The cats were fun. They slouched around, mewling for fish, and, after having feasted upon one’s meager supplies, pranced off to the next poor idiot and repeated the process. I have to be very careful about what I say here. For reasons I have never been quite able to deduce, there is a strong correlation between human beings who support prisoners and human beings who love cats. A Venn diagram of the two would pretty much just look like a circle. So, um… I loved having the cats around. I loved having them steal all of my food. See, look at my eyes, I’m totally not blinking in code or anything. Anyways, the inmates all gave them names which always seemed to me to have more to do with the inmates than the cat: Psycho, Claws, Ratchetbitch. Assigned as I was to the fourth floor, the sparrows were my more frequent companions. It didn’t take them long to peg me as a sucker, and I would save my daily allotment of cornbread for them. This never ceased to amuse me: they were cute little things, though awfully predatory amongst themselves. Much squawking and flapping of wings commenced as soon as crumbs met concrete. Within my first few days at Coffield, they began to congregate on the handrail outside of my cell and chirp-chirp as if they’d die if they didn’t. My neighbors didn’t seem to appreciate the free concert as much as I did. One of them to my right would scream barely identifiable hair metal songs at them, in an attempt to scare them off. He sang like a barn collapsing, but the sparrows didn’t seem overly impressed; neither was anyone else. That was the fourth floor in a nutshell: the Noisily Unimpressed.

So, that’s all well and good. The problem arises when you think about the mess several hundred sparrows leave behind when they strafe the run dive-bombing for crumbs. There are certain portions of the walls, ductwork, and dayroom floors that are so covered in bird feces that one would need to utilize heavy mining equipment before one could even reach the strata of human construction. The stench was pretty constant. You never quite got used to it. It was like a physical presence, the 23rd man in a row of 22.

The showers had an influenza yellow-colored mold growing in it that was probably older than I am. And, considering the fact that it had managed to survive decades of efforts to eradicate it, it would appear to have an intelligence level at least as elevated as the SSIs tasked with cleaning said showers. F-wing was where the kitchen was located for P1, a constellation of six seg halls composing 528 cells. While this afforded me ample opportunities to feast upon ill-gotten comestibles, it also gave me a front-row seat to the practices of your average kitchen worker and an introduction to what might charitably be called the TDCJ’s theory of kitchen sanitation. Coincidentally, around this same time I suddenly found myself unwilling to even touch the trays unless I was absolutely starving and had no choice. Cherish your ignorance, mis amigos. There was a certain afternoon when, as I watched two rats tussle over a piece of salami that had fallen off the trayline, I actually felt a sort of fondness for the relatively white walls found in Polunsky’s 12-Building. That place is the Ritz compared to the penitentiaries of the Tennessee Colony, is all I’m saying.

As hard as that may be to believe, this may be an even tougher pill to swallow: compared to either Michael or Coffield, the administrators at Polunsky are absolute policy wonks. By this I mean: policy, in some bastardized or subjectified form, at least exists in the halls of Death Row. For the most part, you guys get rec and showers at a rate consistent with the Death Row Plan. They don’t even have shower sheets at Coffield, and rec here at Michael happens only when you least expect it. I suspect this has everything to do with the fact that Polunsky is in Region 1, well within the orbit of Huntsville. To extend the metaphor, the five prisons here in the Palestine area (Beto, Coffield, Burney, Michael, and Powledge) are swirling around a much darker star, one that is far more prone to angry, violent bursts of radiation. I suspect it also matters that everyone on the Row has an attorney on their side, someone willing to call up to the unit and figure out why certain problems keep persisting. I don’t know a single person on my pod here about whom this can be said. Navigating the minefield of policy in Livingston is a complicated, infuriating, quixotic business that will make you feel old far before your time. Here, they don’t even pretend policy exists. Strength is really all that matters. When they decided not to give F-Pod a “cold tray” for Christmas, it wasn’t some eloquent paean to the lesser gods of the Admin-Seg Plan that caused the Major to change course, it was the instantaneous and collective decision by about half of my neighbors to attempt to break the world record for officer assaults in a three hour period. (Said Major also came around later, bringing us bags of ODR cookies and apologizing for the “miscommunication.”) The only lesson they seem to teach here is that when someone in authority tells you something you don’t like, if you punch them in the face hard enough, they will go away and you won’t have to listen to them anymore. No wonder our recidivism rates are what they are. These men are all going to be free one day. In some cases, rather soon.

The inherent malleability or even outright non-existence of the rules has become painfully obvious to me in the matter of my continued placement in admin-seg. When I initially passed through Classification at the Byrd Unit, I was told that I was going to be “stepped down” from seg by being placed in some kind of program for men that had spent a significant number of years in isolation. I now know this is the Ad-Seg Transition Program housed at the Ramsey I Unit. I had multiple conversations with several wardens at the Byrd Unit, and they all believed that I would be released shortly into the general population. Each time I spoke to them in the office, I went about sans handcuffs. After my first few nights, they moved me from the high-security observation cells to a normal ad-seg cell. They even let me use the phone to call my father and stepmother.

Something clearly happened on either the 1st or 2nd of March, though I didn’t know it at the time. Early on the morning of Monday the 5th, I was told I was on chain for the Michael Unit. Once I arrived, Major Fitzpatrick informed me that for the moment I was being held in ad-seg, but that they were going to run a Unit Classification Committee (UCC) hearing on me that afternoon. He had a very confused look on his face as he was scrolling through my file on the computer. I assumed at the time that he’d simply never met anyone that had been released from Death Row before and wasn’t entirely sure about the protocol. I was taken into the hallway, put in a holding cage, and left there for six hours. Around 4pm I was told that I was being assigned to F-Pod 24 cell. No one could tell me why I had not seen UCC. The guards seemed to think that I simply needed to wait for the paperwork to catch up with me, that once it did, I’d be off to “the program.”

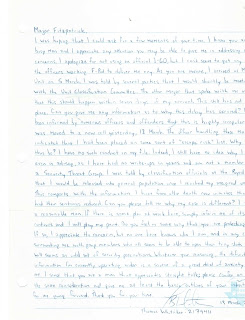

My first real indication that something foul was stalking me came a week later when I was informed that I’d been placed “on rotation.” This meant that I was going to be moved every 72 hours to a new cell. Five other men were on rotation at the time, one of them for a years-long pattern of assaulting officers, the other four having earned this distinction because they had attempted to escape from the TDCJ on at least one occasion (the story of one such man can be found here). None of the officers could tell me why I had been included in this exclusive and annoying club. Confused, I wrote the following letter to the Major on 13 March:

and the following to the head of Unit Classification on the same morning:

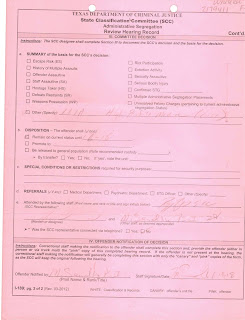

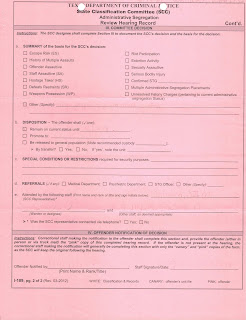

The next day, I was hand-delivered paperwork officially relegating me to admin-seg which you can see here:

I’d like for you to note a number of this document’s features. First, there are two main categories of prisoners placed in seg: those classed as “security detention” and those requiring “protective custody”. For me, the first box was checked. I have heard from a number of you at Polunsky that a certain inmate on the Row has been spreading the rumor that I’m not in GP because I was too afraid to be around other prisoners. Given that this individual regularly starts Category 5 Dramacanes, I don’t really feel it’s all that necessary to defend myself from this charge, but there you go: the “protective custody” box has not been marked on my paperwork. They don’t even have PC inmates in Michael’s seg, for reasons that you can read about here. Second, please focus on the three subfields listed under “Security Detention”: “Current Escape Risk”, “Threat to the physical safety of others and/or the order and security of the prison”, and “Confirmed member of a security threat group (STG)”. The second of these options has been selected, requiring that the “nature of the risk or threat” be listed. Actually, the specific wording states that “if number 2 is checked, the specific disciplinary violations must be cited.” Since I’ve never had a case involving violence or a weapon or dangerous contraband or narcotics, they couldn’t do this. Instead, they claim that I should be in seg based on a recommendation from TDCJ-ID Administration. What does this mean? At the time, I had no idea, but I did begin to think that Major Fitzpatrick’s confusion the day we met had little to do with my former status and everything to do with an utter absence of data explaining my placement in seg. It took me several months of conversations with my peers to figure out that I’m literally the only person on the unit who is in seg for nebulous reasons. Every other person here can point to a reason: their gang status, their disciplinary file, their escapes. Even the guards seem confused.

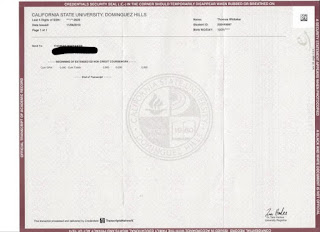

In my naiveté, I made the mistake of simply believing that someone here at the unit level had either made a mistake or had simply chosen to make a statement about my having escaped the needle. After delving into policy for a few weeks, I learned that I was to see officials from the State Classification Committee within a matter of months. The actual verbiage states that I was to see them “sixty days from [my] first seven-day review,” an awkward formulation that nevertheless should have had me in front of the committee on or around the 11th of May. There wasn’t anything for it but to sit and wait – and get moved every couple of days. That got old pretty fast. Ever since I arrived in prison, I’ve been keeping track of the cells I’ve lived in. For the first few years, it wasn’t a very precise list; rather than including the exact day of each move, I merely mentioned the month. I was not, when I arrived here, a person that yearned for precision, though I was starting to see the benefits of such a level of scrutiny. Billy recently had a fun time poking fun at the way I talk and the way I aim very hard at being thorough and exact. This wasn’t the way I was in the world, it’s something prison has taught me. It’s not the result of confidence, it’s the consequence of having made so many mistakes that I now understand I need to plan each step carefully or I’m bound to step on something unpleasant. In any case, you can perhaps detect the way my focus has shifted over the years my reviewing my cell sheet here:

As you can see, in my eleven years on the Row, I lived in exactly 25 cells. I managed to hit my 25th cell at Michael after only 9 weeks.

Unfortunately 11 May came and went without the SCC seeing me. The following I-60 to Classification went unanswered:

Likewise my information requests to the Warden, Major, and Inmate Records. Finally, Captain Inge responded, telling me I would “be seen on June 14th!” The exclamation mark is his, by the way; I suspect by this point I had started to become troublesome. Shocking, I know:

In the weeks leading up to this hearing, I tried to ignore the chorus line of my neighbors who insisted that the SCC was a sham, just another instance of the TDCJ pretending to genuflect to the King of Due Process, all whilst holding blades hidden behind their backs. I prepared as I would have for court, with a massive stack of paperwork listing some of the accomplishments I’d earned on the Row, some of the materials generated from my contacts with the Parole Board, and the affidavits of the officers that had petitioned the Governor for clemency. I thought these things would matter. You’d think I would have learned better by this point – would, in fact, have stopped pretending to myself that one day I was going to meet some actual human beings in this administration.

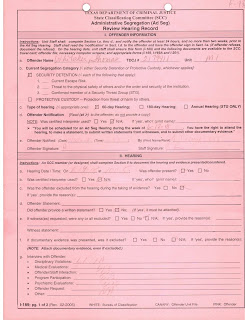

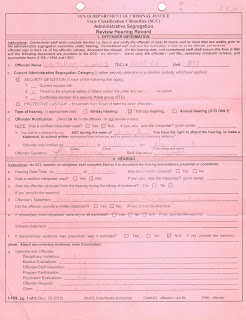

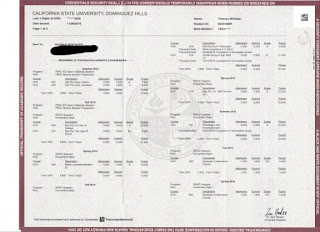

I was not allowed to present any of the paperwork I lugged with me to the “hearing.” I use scare quotes there because if I hadn’t demanded an opportunity to speak, the only listening that would have been done was on my part. The official had, in fact, already filled out my ad-seg continuation paperwork before I’d even entered the room. You can see both pages of this I-189 below:

Note that while “Security Detention” has again been selected as my segregation category, they never even bothered with claiming I was a “threat to the physical safety of others” etc etc… Down below, in section g “Interview with Offender,” under “Disciplinary Violations” they have written “L1 1A”. This means “Line 1, grade 1A,” my classification level at the time. Without getting too far into the weeds on this, “Line 1” signifies my time earning class. All new inmates come into the system as Line 1s, and fall to 2s or 3s when they catch a case, or upgrade into the S-lines when they don’t. This grade of L1 1A simply means that my disciplinary record is clean. Indeed, it is spotless: under this ID number, I have a perfectly clean record – not a single case. I’m now an S4, the best classification grade possible for men in seg. Want to take a guess on how many S4s there are on F-Pod? Gold star for you if you went with “one.”

One page 2 of the form you can see the various reasons for why the SCC might keep a person in admin-seg: escape risk, staff assaultive, etc. None of these categories applied to me. Instead, they began to claim – for the first time – that I had been placed in isolation because my case was too high profile. I honestly wasn’t prepared for this, and it took me a moment to collect my thoughts – a moment when the guards to my right and left were trying to move me along, out of the room. I resisted, politely, asking for clarification. I’m afraid I can’t quite give you the exact response, because it was so nonsensical, I’m not even sure it qualified as actual language. I know that “exigencies” was featured, but it was sandwiched between “understandably” and “numberless variables,” a sort of Big Mac of bureaucratic nonsense with a hefty dose of “fuck off” special sauce. Of course this verbal disaster track ended in: “Does this clarify the matter for you?” because in the TDCJ we like our absurdities to come in Family Pack size.

“Let me see if I understand this… you are saying that you are keeping me in solitary confinement…for my benefit?”

“Well…your case was very high profile. It was all over the news.”

“Has there been a threat against me?”

“Not that we are aware of.”

“So this is about a hypothetical threat…while at the same time claiming that I myself am a threat to the very order of the prison.”

“That is what Huntsville is telling me, yes.”

“So I’m someone that is so dangerous that the prison itself needs protection from me, while simultaneously being so vulnerable that you need to protect me? Do I have this correct?”

“Uh…”

“And you are making this decision despite a total absence of my having exhibited violent behavior or tendencies in prison, and despite the fact that I am not requesting protection, and, indeed, you have not placed me in a safekeeping wing or even indicated on my paperwork that this is the case.”

This earned me a very long look, followed by a series of loaded ones between the various officials present. One of the women seated at the table suddenly developed a very intense interest in the paperwork sitting on her lap. Her makeup, I noticed, didn’t quite reach her hairline. It so reminded me of a mask that I began to wonder what I would find if I were to peel it off.

“Mr Whitaker, do you still have an attorney?”

The answer to this wasn’t entirely clear to me. While still maintaining a strong connection to the team that represented me during my appeals and at clemency, these men had all moved on to their other clients, who were obviously still in crisis. I did have a lawyer that had made a point of coming up to see me in Tennessee Colony a number of times, but this relationship was more personal than professional at this point. Still, it seemed like the panel was looking for a specific answer, so I nodded to them in the affirmative.

“My suggestion to you is to have your lawyer call the media relations office. That’s where a high profile media tag would have to come from.”

Looking at the man, seeing the peculiar look on his face, told me he knew all of this was BS, that he was having to say it because he’d been told to do so. I once again recalled the look of confusion on Major Fitzpatrick’s face as he was reading my file on the screen, and I suddenly realized that I would have given a digit to have had access to what he was looking at. And then it hit me, hard: this was going to take a long time to fix. This was going to take years.

The following weeks were not wonderful for me. I vented my spleen by dusting off my grievance cannon and giving the state a series of broadsides. On 19 July a man upstairs died. The reason given to an associate of mine here is that he ruptured his gastrointestinal tract. Maybe. But I also know that he was covered in blood when they brought him downstairs, and that when OIG came to investigate, Officer Davis took the temperature reading in his cell and was overheard by all of us in 5-Section to say that it was 120°F. I mailed out a letter to the Texas Civil Rights Project a few days later, which, I would soon learn, never arrived. Instead, two weeks later, I was shipped off to the Coffield Unit.

Once there, they actually ran UCC on me while I was present, my first time in fourteen years. There I experienced a spot of luck, for the Major in charge of the hearing was an old convict boss. He admitted to me flat out that he had no idea why I was in seg, that according to my file I ought to be in a dorm in population. My jaw would have dropped, had I been prone to such things.

“There’s no justification in the file? Nothing about my case being high profile, about you guys needing to move me every 72 hours?”

“Move you every 72 hours? I wouldn’t move the Devil that often. No, once you are assigned to a cell, that’s where you are staying. And I do see the high profile tag, but there’s no reason for it listed. All it says in the file is ‘CID’ and then lists a phone number.”

“I see.”

“Want to guess whose office answers at the other end of that number?” He seemed to be enjoying this. His smile was playful, and when I told this story to some of the men in my hall later, nearly everyone said he was a good officer. I didn’t even know where to begin on my list of suspects, so instead I simply told him the first answer that came to mind: “Barnum and Bailey Circus?”

That got an even bigger grin. “Nope, but pretty close. The number went straight to Bryan Collier’s office.”

This truly did surprise me —surprised and unnerved me at the same time. “The Executive Director?” I mumbled, stupidly.

“Yessiree. When you decide to piss off the man, you go straight to the top.”

This was in August, and, unfortunately, I haven’t made much progress since. For reasons that remain unknown, my little field trip to Coffield lasted only four months. On 30 November, the unseen governors of my life shipped me back to Michael Unit. While I’m all but certain that the two are not related, the state managed to get some added benefit from this move, in that it effectively mooted a series of grievances that were working their way through the Step 1 process. By moving me, they prevented me from being able to file a Step 2, the portion of the grievance system answered in Huntsville. Two weeks later, I met with SCC officials again on 13 December. This time, there was no mention of my “high profile media case.” The committee once again admitted they didn’t know why I was in seg, only that they couldn’t let me out. One of the classification officials from Michael asked me to step back, and then began whispering to the functionary from Huntsville. I could hear about half of what was said, and this included words like “commutation” and “risk.” When it was all said and done, I was told I had to petition Bryan Collier in order to be released from seg.

I’m trying very hard not to jump to conclusions about any of this. Still, it’s really starting to feel like when my sentence was commuted to life in prison, somebody high up in the system decided to keep me permanently consigned to solitary confinement, instead of following their own procedures and rotate me into general population. There doesn’t appear to be much I can do about his now, save remain patient and try to learn whatever lessons Michael Unit can teach me. For those of you reading this that never liked me much and are hoping that I am suffering, take solace, for suffering is never far from me. For those of you that were my friends, take heart, for I am enduring, and my goals and dreams have not been wounded by anything that has been done to me since we parted. I owe much of my resilience to the example many of you set for me during our years together, and for that, you have my eternal gratitude and loyalty. If there is anything any of you need, you know where to find me.

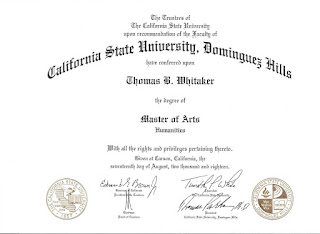

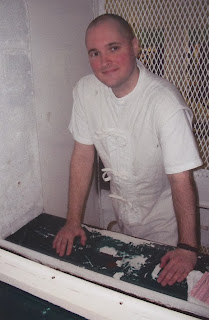

In the midst of all of this gloom, I did have a number of victories. Most of you knew that I was working on my Master’s degree the past few years. I actually completed the coursework a while back, but was having some issues completing my thesis. The thing shouldn’t have taken me longer than a year, but it turns out it’s not so easy to do genuine scholarship without access to search algorithms or interlibrary loans. Essentially, I had a number of core books, and I mined the bibliographies of each for the next round of research. Those bibliographies suggested new jumping off points, and this wandering eventually got me to where I needed to go. That, plus I had the assistance of long-suffering (and I do mean looooooong-suffering) friends, who kindly wore out their printers sending me all sorts of data from scholarly journals. My thanks to all of you, and I’m sorry it took me this long. In any case, I finished my thesis in January 2018, 38 days before the state planned to kill me. The finished product, titled: Who Fears Hell Runs Towards It: On the Christian Metaphysical Foundations of the American Penitentiary and the Missing Image of Resistance in Foucault’s Discipline and Punish is currently being edited for publication, and has already earned the distinction for having the longest and most unwieldy title in the history of literature. It ended up being a tad long. Turns out theses clock in at around 100 pages or so. Mine was just under 500, a point that nearly caused my Harvard-educated advisor Dr Lyle Smith to have an aneurism. I managed to cut it down to 170-ish, which basically pleased no one, since the Cal State committee still felt it was too long and I felt all of the good parts got left out. Such is life. It took the university a number of months to approve the final version, and then a few more months for this to come in the mail:

I’m still hoping to find a university willing to let me work on my PhD, though I admit I haven’t had much luck on that front yet. It was always going to be a long shot. What in our lives isn’t?

Perhaps the high point of my year arrived in October, when PEN America named me a Writing for Justice Fellow. More than seven hundred journalists, academics, artists, polemicists, and essayists submitted project proposals in the contest, and I was selected as one of the ten winners (details on the other nine can be located here). I was not expecting to win, and upon hearing the news immediately began feeling like the dog that finally managed to catch up with that car it is always chasing, and now isn’t entirely sure what to do with all of this chrome between its jaws. My project, Dividing by Zero, consists of a series of hybrid long-form journalism/memoir articles about my months living on Deathwatch. The final version will be released in May at the PEN World Voices Festival.

As many of you are aware, I have a longstanding policy of not profiting financially from my writings that deal with prison or my crime. Given this, I donated the entirety of the $10,000 prize to my father, as part of a victim’s restitution project, and to a number of charities, including MB6 and The Prison Show on 90.1 KPFT. We are regularly told that our lives are without value, that we had to be sentenced to death because we are fundamentally incapable of contributing in a positive way to society. I can think of almost no one on the Row about whom this might be true. With these donations, I hope to show the exact opposite: a year ago, the state was attempting to murder me; now I’m a PEN Fellow and a significant donor to several worthy causes. Food for thought to the Pro-DP zealots that like to cruise through these pages looking for more reasons to hate me.

I continue to miss all of you. The experiences of living with a death sentence produced profound changes in all of us, and this has only become clearer to me as I’ve had the opportunity to contrast and compare my friends on the Row to the men I’ve met here. In every section down there, I could find men willing to discuss politics, history, sociology, the classics, science, virtually any subject one can think of. Here, all anyone cares about is getting “tooned out” (getting high on K2) or starting some petty drama. I’m not one that believes in the power of intercessory prayer, but living here constantly reminds me of the one prayer Voltaire ever offered to God: “O Lord, make my enemies ridiculous. And God granted it.” If there’s any bit of wisdom I can offer you, it is this: hate that place with a passion, do everything in your power to deny the state its goals, but try to look around you once in a while and appreciate the quality of the average prisoner. There are many worth standing beside, many worth falling for. And that’s a rare thing, my brothers, a very rare thing. Beyond that, I’m still battling these people, and I’m standing with you, just a hundred miles or so up the road. Ecrasez l’infame, my friends, crush the fucking thing. Pax.

With Compliments,

TBW

10 Comments

Mari

July 21, 2020 at 1:57 pmI fear that the prisons in Texas will purposely try to make your life hell as retaliation for your clemency. I hope you are able to get visitors and mail.

Mr. Gray

June 25, 2020 at 2:12 pmWas wondering how things turned out for you. Great account of status apres DR. Congrats on the hard work. Prieto would approve.

Mr. Gray

Thurston

January 12, 2020 at 10:48 pmThomas has been absent for going on a year now. I hope you are doing ok, sending good energy your way.

DebittNJ

May 12, 2019 at 4:54 amI’m speechless. To think that after DR it could get worse. As always your writing is highly entertaining and above all thought provoking. Looking forward to your essays. Congratulations on the PEN Award. Hoping your situation has improved since this was written. Best regards.. Debi

kaori

May 8, 2019 at 6:52 pmIt was great.Also Congratulations! I'm looking forward to read your work for PEN.

I hope things get better for you.

Also,I leave lighthearted comment here.

I'm guilty for loving cat also supporting prisoner.I don't know why,there are lots of these people.

Don't worry,I didn't get any code from you..

Unknown

May 7, 2019 at 1:32 pmI must admit, I thoroughly enjoyed this read. Looking forward to reading more from you soon

FreeClintonLeeYoung

May 2, 2019 at 3:51 amTHIS WAS KICKASS!!! I'M GLAD YOU STAND UP FOR WHAT'S RIGHT AND YOUR BROTHER'S IN THE ROW ARE SO PROUD OF YOU I BET!!! IDK IF THESE COMMENTS ARE EVER READ OR WROTE TO YOU IF THEY ARE KEEP TRUCKIN JUST LIKE THR GRATEFUL DEAD SONG!!! -DONNA

rabbitholedigger

April 28, 2019 at 6:47 pmGreat read, Thomas. Everything seems to be moving forward for you, despite the setbacks. Do you have access to TV or radio in your new abode? Or is just the same kind of seg you had at Polunsky?

urban ranger

April 27, 2019 at 1:02 amAlways look forward to seeing a piece by Thomas.

Things sound pretty rough – maybe improvement since

this was written? Important to have a sense of being settled,

no matter what the circumstances.

All the best to you, Thomas.

gord

April 26, 2019 at 1:46 pmCongratulations Thomas, excellent read. In my books you’re a man of honour.