Rest in Peace

By Gerald Marshall

After a judge instructs you to stand up, then tells you that you will be handed over to the Texas Department of Criminal Justice until your sentence or death is to be carried out, you wonder about a lot of things. For me it was “when am I going to die?”

After being sentenced to any length of prison time in the Harris County Jail there is a normal wait period of 30 days and after that time you’ll be sent to prison, or TDCJ where you’ll start serving your time. After I was sentenced to death I figured I’d wait about a month to be shipped to death row, wherever that was. On November 11, 2004 an officer came in my cage through the speaker in the wall saying, “Marshall?”

“Yes,” I responded.

“Pack your shit, you’re catching chain.”

Catching chain meant I’d be shipped to death row, TDCJ.

“Huh” I responded, caught off guard.

“Pack your shit,” he said confidently. “You’re being sent to death row today.”

Twenty minutes later I was loaded into a white van after doing the normal humiliating naked strip search. I didn’t know where I was headed. I just knew that I was defeated and I sat there shackled from my feet to my waist walking like an elderly man trying not to hurt himself. I was headed to Death Row. The van ended up taking me to Huntsville; it was my first time ever in a prison. In prison bars are everywhere, the prisoners all wear white, and the guards, grey. They even instruct family members and friends who visit to not wear white so they won’t be mistaken tor a prisoner.

At the Huntsville unit, I was strip searched again, shaved and taken to be processed. The lady in processing asked me numerous questions, like where was I born, education, and family background, then a photo was taken to be used on my prison identification card and finally I was given a TDCJ death row number 999489. From there I waited to be transported to the Polunsky Unit where they house Death Row prisoners.

The guard who came to transport me asked me my number. “What number?” I responded,

“From now on you’ll be known as a number, not by your name. You’ll need to remember it; it’s 999489. Got it?”

“Yes,” I’d respond so the conversation could end. As we drove to Polunsky he began making it a point to ask me my number.

No answer. Instead I’d curse him out to myself, and start laughing hysterically. He looked at his co-worker and uttered, “He’s crazy.”

I knew nothing about Texas Death Row when I came. I figured in a few weeks I’d be executed like Gary Graham, even though like Graham I’m innocent. Like him I thought I didn’t stand a chance. I was completely ignorant to any appeals process. I thought we‘d all be dead, and dead soon. When I was housed around the other prisoners, I’d ask when would they kill us only to be told, “they aren’t killing me” by several prisoners. Not totally understanding, I’d next ask where were the TV’s, and every one would laugh at me; there was no TV, just solitude and neighbors.

My first two neighbors on death row were Hispanic and Black. The Hispanic and I talked a lot. He was recently at Huntsville, on the execution table, ready to be killed, only to be told that he had received a stay of execution.

He described to me how the recreation system worked. Recreation was an hour in a bigger cage right in front of the dayroom. He explained breakfast, lunch and dinner, and told me that the food was trash. He said some guards were assholes, and some were just coming to work to do their jobs. Though I heard what he explained to me over the next few weeks I still couldn’t comprehend that I was on Death Row.

The neighbor to my other side was an African American named Beunka Adams. Beunka was short and stocky and we instantly clicked because we were both 22 when we came to Death Row. He‘d been here six months before me and we were both still learning the environment. When prisoners are neighbors on Texas Death Row they usually become close. Until a year ago there were huge holes in the back of the cage walls. Two prisoners who were cool with one another could talk for hours if they choose to. Some holes were so big that you could fit food through them. Another way prisoners can bond is through the outside recreation yard. Outside there are only two prisoners, and you can talk about anything and be really private.

In 2004 the way they housed us was simple; you would be in a cage for a long time, some times you would stay in one cage for years, and you would be with certain individuals and wouldn’t see others for years at a time.

While Beunka and I were housed around each other we would use this opportunity to get to know each other. We’d spend days outside talking about our crimes, how they came about and the regrets we’d have over our short lives. You could tell that Beunka was a country kid; he and I didn’t share the same views on everything, but we came to know each other as brothers. Death Row brothers.

Beunka cared what other people said about him. On the other hand, I couldn’t care less because I was so talked about as a kid. I’d tell him, as long as they didn’t put their hands on you, don’t worry let them talk.

Beunka began suffering from paranoia, a symptom of being isolated for long periods of time. Beunka and I were separated for about a year, then when I finally saw him again he was visibly suffering, barely keeping his self up, asking guards and prisoners if they were conspiring against him, sending me messages on paper, called kites, asking me if this person or that person was talking about him. It had gotten so bad that I responded to him in a kite with an article I’d just read about isolation.

The article, titled “Annals of Human Rights” by Atul Gawande, talked about a professor doing a number of experiments on monkeys. It described how the monkeys reacted to being isolated for long periods of time, the symptoms and how these symptoms were found in humans who were isolated like the monkeys. The article made me look at myself and observe my own behavior to ensure I wouldn’t succumb to my environment. I then sent the article to Beunka telling him that he needs to stop being paranoid because he was succumbing to being isolated, and if he couldn’t I wouldn’t be able to continue passing kites with him, the situation was just to serious for me.

I didn’t get a response from him for some days, and then I finally did. In the kite he thanked me for showing him the article, and he realized he was suffering from being isolated. He immediately started to act like the Beunka that I knew when we first met.

Over the course of seven years, Beunka and I were best friends, brothers, fathers and prisoners together. We’d talk about his appeals every time we saw each other, and he’d brush it off saying that they’d kill him no matter what. Though I hated to hear my brother talk like this, the truth is, Texas forces us to live out our last days here within these walls.

Beunka was on Death Row under The Law of Parties. This law means that even though you don’t kill any one directly, if your co-defendant does, then you can still be held accountable. Beunka was on Death Row never having killed any one himself, and on the 25th of April his last statement was: “I’m very sorry, everything that happened that night was wrong.” You all may not know it, but he was a changed man who is now no longer able to bless us all with his smiles and great poetry.

The Sunday before they executed Beunka, I saw him for the last time at a legal visit. During a legal visit, two prisoners are allowed to help one another with legal work. It was an emotional visit, just thinking about losing a loved one in this manner hurt, and it hurt even worse to look at him trying to hold on despite watching others around him executed. We talked about the hope of his getting a stay of execution because of a case that was pending in The United States Supreme Court. His last hope was a stay on this issue. We then talked about how he would get married soon and how much he loved his future wife, and how we would proceed if he did indeed receive his stay.

The last few minutes we’d argue like we were accustomed to about some minuscule point only to laugh it off. Then we expressed our love for one another and thanked each other for seeing one another as people and not numbers. It was the last time I’d near his voice, and the last time I’d see him.

When the state of Texas executed Beunka, I couldn’t sleep, I just walked in my cage, waiting, hoping to hear if he received a stay of execution or not. It was sad then, and

it’s even sadder thinking about how I lost some one I knew better than my biological family. Then I heard on the radio that he’d been executed, I thought to myself, “we’ve lost a portion of the battle, but we must keep fighting on.” Not only for me, but for him, and the three kids that he left behind.

May he rest in peace.

|

| Gerald Marshall |

If I had one sentence to add to my tombstone it’d say, “He tried.” Every day I try to be a father, a friend, and some one I can be proud of so that if I am executed I can die peacefully. I hope these words touch, as they come from my heart. Any questions can be directed to me at:

Gerald Marshall #999489

Polunsky Unit

3872 FM 350 South

Livingston, TX 77351

USA

|

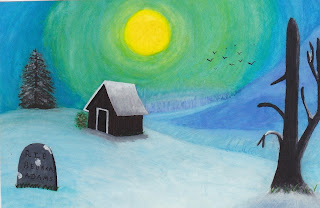

| The above is a painting Gerald did in honour of Beunka Adams |

The Longest Hour

A tribute to Manuel Pardo, executed on December 11, 2012

By Michael Lambrix

It’s now been more than a generation since the Vietnam War ended and the troops came home. But on Tuesday, December 11, 2012, another soldier lost his life because of that war. Manuel Pardo was a young man from New York who proudly volunteered to serve his country and did so with honor, even when he found himself serving a tour of duty in Vietnam as a Marine, during the final months of that war.

I personally knew Manny for over twenty years, in ways that only someone living in close proximity to each other in solitary confinement can. He never bragged about his service, as he was a modest and humble man who didn’t suffer the insecurities of character only too common amongst most prisoners. But little by little I learned a lot, and I have no doubt that if not for the trauma he experienced in Vietnam, he would have never come to Florida’s Death Row and his life would be continuing today.

Manny was raised in a strict Catholic family and was a son any father would have been proud of. In his Hispanic community, he was respected without exception and with good reason. While growing up, he served as an altar boy at his local Catholic church, and it was no surprise when he announced that he had enlisted in the Marines so that he could fight for his country.

After coming home from Vietnam, Manny’s dedication to the service of his community compelled him to go into law enforcement. He met his soon-to-be wife, and they started a family. His daughter is the same age as my daughter, and through the many years we knew each other, we often talked about our children – even just before they signed his death warrant. I would tease him, telling him that if his daughter didn’t hurry up and give him some grandkids, I would give him a couple of mine, just so I could see him out in the visiting park trying to keep up with the little rugrats…that always made him smile.

At some point, his quintessential American “dream” took a turn towards the dark side. Back then, South Florida held the highest rates of homicides in the country, mostly attributable to the violent drug underworld that infested the area. Working in law enforcement in that area put Manny front and center, and like most enlisted Marines, Manny wasn’t one to back down from a good fight. He never denied killing quite a number of South Florida drug dealers, even having the audacity to tell the media that Florida should thank him for taking out the trash – that was Manny, and he gave no ground.

But what only few know is that Manny did not simply go on a psychotic killing spree. There’s more to the story than what the State would have us believe. Rather, these drug traffickers brought the war to him, threatening his family and causing him to respond as his military training had taught him to do. Once that line was crossed, he was committed. And in his mind, he truly believed he was doing the right thing.

The State of Florida convicted him of nine counts of capital murder and sentenced him to death. The Courts refused to give any meaningful consideration to Manny’s military service, and Manny didn’t ask for any. He was one of the very few I have ever known on Death Row who never once argued he was innocent, or that his life should be spared. Instead, he accepted his responsibility and the consequences of his actions, and made it clear to his lawyers that he would allow only one round of state and federal appeals, and then would welcome a death warrant. It wasn’t that he wanted to die, but that he had the integrity to accept his fate and was not afraid to face that fate, just as he did anything else, with stubborn pride and his chin held up high.

In October, the Governor signed a “death warrant” scheduling Manny’s execution for December 11, 2012. I was a few cells away from him when they came to get him and he was immediately transferred to nearby Florida State Prison, where Florida’s death chamber is. Being only too familiar with that particular wing myself, I knew that Manny spent his last six weeks in that same solitary cell, only steps away from that solid steel door that led into the execution chamber – the same cell where I too had awaited my fate. (see: “The Day God Died”)

But even as much as I know that Manny was been at peace with his fate, I know too that he suffered greatly knowing what his ritualistic death would do to his daughter. I know that he would have given anything to spare her that pain.

Nobody ever talks much about what execution does to the loved ones the condemned man leaves behind. I have no doubt that his daughter has his strength of character and perseverance. While children of any prisoners, especially Death Row, grow up with problems of their own, his daughter worked her way through college, and then law school, and Manny’s pride in her shined through like a beacon in his dark world.

But I also knew nothing could have prepared his family for what they would endure. The warden had scheduled his execution for 6:00 p.m. that Tuesday night and as protocol dictated, Manny was prepared and delivered to the execution chamber, then laid down and strapped to the gurney, and the needle inserted into his vein. And then they would wait.

Manny’s lawyers had filed numerous appeals in the weeks before his scheduled execution, primarily challenging the means in which Florida is currently putting condemned prisoners to death. Due to previous legal challenges, Florida has changed its process numerous times in recent years – but refuses to publically release the protocol currently employed, leaving lawyers to speculate that this secret protocol may lead to yet another botched execution similar to too many others in Florida in which the condemned man is essentially tortured to death, slowly.

Even as Manny was strapped to the gurney and ready to go, the appeals were still under review before the U.S. Supreme Court. The witnesses who had volunteered to watch him be executed sat in their chairs just on the other side of that glass partition, probably growing uncomfortable as they too sat in prolonged silence, not knowing what the delay was.

Then there was the crowd gathered outside the prison, just across the road from the prison gate. They stood in solidarity and prayerful hope that the delay would mean the execution was called off, just as it had recently been for John Ferguson when he too came so close.

Off site, Manny’s daughter and other family members gathered at a Catholic church where the priest who often visited Manny tried to comfort them, and they all anxiously awaited any word of what was going on. At the prison, Bishop Snyder personally sat near Manny as he remained strapped to that gurney.

Nobody could imagine the trauma so callously inflicted upon Manny’s family as one minute ticked away at a time and they anxiously waited for any word at all. And with each moment that passed, I have no doubt that another permanent scar was branded upon their soul.

It took one hour – the longest hour imaginable, before the U.S. Supreme Court finally denied Manny’s last appeal and immediately after that phone call came, the State’s executioner wasted no time in pushing the plunger down and sending that lethal cocktail of chemicals into Manny’s veins. The next day the Catholic priest that stayed with them that last hour came to the prison to visit me and give me Manny’s last regards. He was gone, but he died peacefully. Now those who cared for him must bear the burden of that loss, as the pain inflicted upon his family will not soon fade.

Manny was a devout Catholic, even to his last days. He was a man of extraordinary moral character and integrity. As one can imagine, coming to prison with all the convicts knowing you were a cop can quickly make your life hell, but through the years, Manny gained the respect of even the hardest convicts. He was as straight as any man can get in here, and stood his ground solidly as a rock when he had to.

Manny and I used to joke about what our first ten thousand years in purgatory might be like. Other than the overwhelming pride he had for his daughter, Manny was fanatically passionate about his ancestral home in Spain, especially their football (which I loved telling him was not football but soccer, and he would always then go on for an hour about how Americans don’t know what real football was!), and the bullfighting and even the running of the bulls each year.

So, since Manny has taken the trip across the River Styx before me, I know now what to expect when I get there…when I get to purgatory, I’m sure I will find Manny there still complaining about his soccer team not doing what they should have done, while doing all he can to get the latest magazines covering his beloved bullfighting….I wouldn’t even be surprised to find him cornering the great matadors of the past, and picking them apart with never-ending questions. And all the while, he will have that picture of his daughter that he’s kept on his T.V. through the years there at his side. And when he sees me, he’s going to smile, and give me a brotherly hug, and say: “hey, amigo – what the hell took you so long?” That’s Manny.

-The End-

|

| Michael Lambrix was executed by the State of Florida on October 5, 2017 |

No Comments

A Friend

February 27, 2013 at 6:46 pmThe following comment posted on behalf of Mike Lambrix:

Thank you for your comment regarding my tribute to Manny Pardo. I do understand how difficult it can be to se the good in someone convicted of such acts of brutal violence. It is unfortunate that we live in a society that sees only the worst side of others and in all honesty, I struggle with that myself from time to time. One of the truths I have come to understand in the too many years I have spent wrongfully convicted and condemned to death is that within each of us there is the capacity for both unspeakable evil and infinite good. Too often the path that led someone to prison is influenced by factors present in their lives at that particular time and only when removed from that environment, even if it’s a cage on Death Row, they get in touch with their true self.

My tribute to Manny is based upon the man I came to know in the many years after his crimes. I do not honor or pay tribute to any act of senseless violence but only ask that each of us at least try to find the good in others, as only by finding the good in others can there be any hope of others finding good within us. Perhaps if you had come to know Manny for the man he became in the years after the crimes, you would have seen him differently too.

Unknown

January 30, 2013 at 6:40 amTo Mr. Lambrix in reference to "Manny".

As you put it a "extraordinary moral character and integrity", would not kill 9 people, 6 of only he admitted to. He was apart of the Florida Highway Patrol, but was fired because he falsified tickets. Is that a sign of integrity! He was fired from Sweetwater squad in Florida, b/c he lied in the Bahamas about his colleques being international undercover agents. If that's integrity to you, then no wonder why you are in the position you are in. Yes, your friend has passed on and his debt to society has been paid. It's o.k to even say kind words about him, but to chalk him up to be the "great" character is hardly even close to what he was. He killed, for whatever reason, he took at least 6 lives that where not his to take. That's wrong, PERIOD. Drugs or no drugs, threats or no threats. Did he tell you that eh killed these people and took their credit cards and used them. Tracked the murders by keeping clippings from newspapers, and wrote about the murders in his diary! That's sadistic and disturb, for you to look up to a man such as this, is even more disturbing.