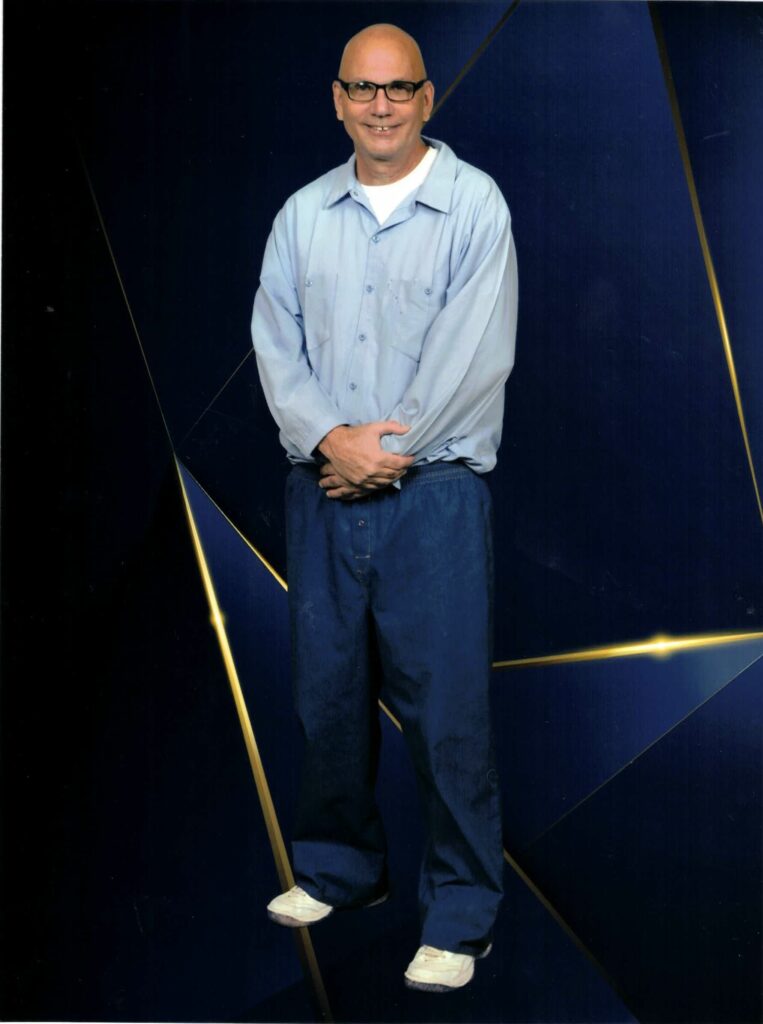

“Did you know they’re sending LWOPP’s to the dorms?” Reggie, my sixty-year-old buddy, asked me.

Although he had a few more months on earth than me, I’d spent more years in custody than

Reggie. We were both closing in on our fourth decade behind bars.

Turning away from my sewing machine, I questioned, “What are you talking about?”

“Jeff’s LWOPP, and he just went to his annual. Classification endorsed him level two dorms.

Man, I’m freaking out! I go to my annual next month.”

Me too.

Life Without Possibility of Parole (LWOPP) prisoners had been placed for decades in level four prisons. Only in the past half-dozen years had we been allowed to drop to level three if we maintained good behavior. Level three and four have electrified perimeter fences and are both considered high security with prisoners housed in cells. Although the cells were built for one prisoner, custody welded in a top bunk and magically made them two-man cells, tight quarters but still much, much preferable to a dorm setting with multiple bunks.

When I had been a level four prisoner at Pleasant Valley, I had worked as a clerk in the law

library before becoming a sergeant’s, then lieutenant’s and finally a captain’s clerk maxing out at fifty-six dollars a month.

After two years sewing at Sierra Conservation Center’s Prison Industry Authority — Fabrics, I was making one hundred dollars a month as a single-needle operator assembling California Transportation (Cal Trans) vests and overalls and California Fire (Cal Fire) shirts and pants. Frequently, overtime was offered, and I could make one hundred fifty dollars a month if I sewed eleven hours a day Monday through Friday and seven hours on Saturday. Good money for a prisoner.

In two years, I had progressed from a “D” number to a “B” number after passing written and practical tests and was next in line for an “A” number which would give me more responsibility and pay.

Reggie had one of the six “Double-A” numbers in the shop. He was in charge of line two and made thirty percent more pay than me and earned it. Bolts of fabric shipped from China would arrive for cutting, bundling, and then the cloth was sent to the prep or assembly areas for single needle sewing, over lock, bar tack, and finally quality control inspection.

When I was Captain’s clerk overseeing two other clerks, I had tremendous difficulty keeping them on the same page. Reggie’s job supervising sixty unrepentant felons out of a shop employing 150 criminals seemed beyond challenging, almost impossible. Two years ago, when I first started sewing on line one, we consistently passed three hundred vests a day through quality control ready for shipping. Line two’s lead man had placed his homies in positions of authority alienating the rest of the workers.

Discontented criminals slashed or poked holes in the fabric and line two was lucky if fifty vests a day passed quality control. The Superintendent announced that sabotage would not be rewarded, and he would not make any changes to line two.

Alarm. Line two’s lead man was carried out with a broken jaw and holes poked in him. The Superintendent designated the former lead man of line two Employee of the Month and placed the certificate in his central file. I’m sure that eased the pain. Reggie took over and through relentless, positive attitude, encouraging the best workers, he had thrived, and now line two was on par with line one.

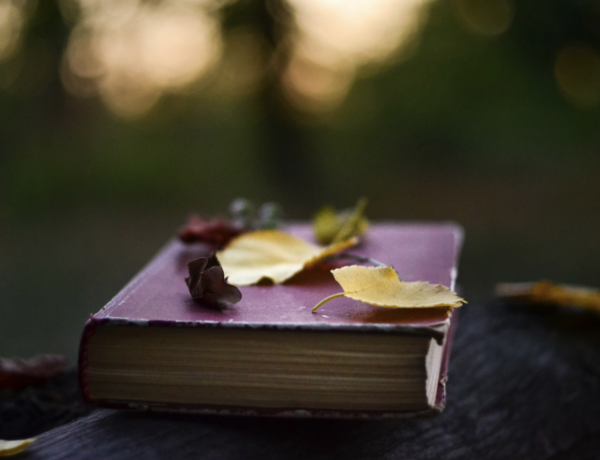

I really liked Sierra Conservation Camp. Located in the foothills, I’d walk to work and view just outside the fence, deer loping, squirrels darting, rabbits peering back at me, wildlife all around. On break, I’d wander with a mug of coffee, settle onto one of the wooden benches scattered across the grass, and look up at the forested peaks and spy hawks circling, dancing in the sky. The money was good, but the work was better.

As a custody clerk, I typed rules violation reports, disciplinary hearings, lockup orders, pretty much adding to prisoner misery. I felt a sense of accomplishment when I finished sewing. I was especially satisfied when I sewed garments worn by Cal Fire. Knowing the clothes I sewed could save someone’s life while they battled a wilderness fire gave me a feeling of contribution. Now with the prospect of transfer to the dorms, all of that was in jeopardy of going away.

“I find it hard to believe they’re housing LWOPP’s in a dorm setting,” I replied to Reggie, “they would just be asking for a body count. I’ll go to the law library and check it out.”

In the library I read that the voters had passed Proposition 57. Among other policy changes, they now allowed LWOPP prisoners with good behavior records to be housed in level two dorm settings. I also noted there was a list of administrative determinants that would keep a prisoner in a higher level of custody.

For example, if you were a member of a security threat group, you could be held at a higher level than your disciplinary record might otherwise reflect. Another administrative determinant was if the prisoner was formerly housed on Death Row awaiting execution.

From 1984 to 2002, I’d been on San Quentin’s Death Row. I received a new trial and was sentenced to LWOPP plus two years. The two years would begin when the Life sentence was completed. Whatever.

I gave Reggie the bad news and started sending Requests to Interview to my counselor, asking to speak with her about applying for an administrative determinant. I received no response.

The Superintendent spoke to Reggie and me about our possible transfers and then handed each of us critical worker chronos, asserting that we had skills essential to shop operations.

Called to our annual reviews, Reggie went in first and classification committee refused to honor his chrono and put him up for transfer to Valley State Prison. Figuring if they wouldn’t honor Reggie’s chrono, I’d have no chance, so I simply spoke to them about my history on Death Row. The committee told me the administrative determinant was only available to current members of Death Row.

This seemed nonsensical. Condemned prisoners are commitments to the Warden of San Quentin not the Department of Corrections, so they would not be subject to any transfer much less to lower security dorms. I tried to argue but was cut off by the Captain. I gave up, got up, and started to leave.

“Didn’t the Superintendent give you a critical worker’s chrono?” the Captain asked.

I nodded yes.

“He has a year to train your replacement because we’ll be sending you to the dorms at your next annual.”

Surprised at the reprieve, I went back to work.

Some weeks later, Reggie transferred, and his first letters were upbeat, optimistic. Reggie’s dorm housed eight men. The guards knew it was good compared to dorms with forty or even two hundred bunks and would threaten to send you there if you didn’t instantly comply with each and every whimsical notion flickering through their brains. He had put in an application to work in the Prison Industry Authority—Optical and was excited to have a chance to learn how to make prescription glasses.

A bit of time passed before I heard from Reggie again. He received an assignment ducat for optical, reported to the work gate and the guards told him they didn’t give gate passes to lifers.

“The voters want lifers here,” he wrote, “but the guards don’t like it and won’t let us work in Prison Industries.” Since he couldn’t pass through the gate, he was reassigned as a table wipe in the dining hall making twelve dollars a month.

A few more months went by, and I received a letter from Reggie now housed in the hole. After wiping down tables, he returned to his dorm and discovered he’d been burglarized. Although each prisoner had a locker he could secure, they were small, and you couldn’t keep all your belongings locked inside. Reggie had just received a quarterly package and placed some of his property in a bin under his bunk and the bin was gone.

“Who took my stuff?!”

“I did,” a twenty-something-year-old car thief answered. “What ya gonna do about it, old man?”

Although Reggie limped around smothered by a green vest with “HEARING AND MOBILITY IMPAIRED” lettered on the back, he had also done decades in hard core prison, survived mayhem, melees, riots, and violence that a car thief doing a three-year bid could not possibly imagine in his personal philosophy. The fact that Reggie was still moving should’ve told the youngster something, but he just wasn’t listening.

Shaking his white-haired head, Reggie secured a tomahawk, a razor blade taped to a handle, caught the car thief playing poker and slashed his face. Blood, alarms, youngster went to the hospital where he survived but with a permanent scar that would force him to think of Reggie every time he looked in the mirror.

At committee in the hole, the Warden yelled at Reggie, “That’s why I don’t want murderers in my prison. Can’t keep your hands off the youngsters!”

“Tell your youngsters not to take things that don’t belong to them to pay gambling debts.”

With good time, Reggie would be out of the hole in two years, but probably not to a dorm ever again.

I thought a lot about what happened to Reggie. I really didn’t want to hurt anyone, but I didn’t want to be a victim. Keeping myself out of the dorms just might save someone a whole lot of hurt. Maybe that someone was me.

Turning the problem this way and that, looking at it from various angles, a solution wasn’t readily apparent. Sometimes in prison you have to engage in out of the box thinking.

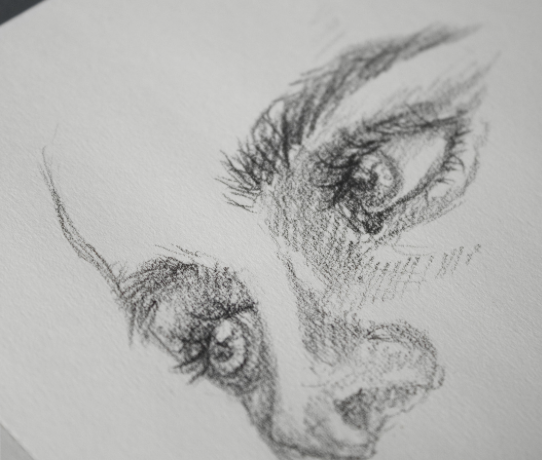

Rob, a guy I knew on Death Row, was a serial killer, he had cold blooded, reptilian, predator eyes. With no friends, just victims, beyond bars, he couldn’t purchase a television. Repeatedly, he asked his attorney to buy him one and the attorney refused. I never watched television prior to prison, I received the news through the radio, newspapers, and magazines, but locked in a Death row cell for hours a day, television becomes a window on the world.

Rob told his attorney, “You receive a lot of money for filing death appeals which are going to be denied and I’m going to be executed. At best you can string out my execution a few years. In the meantime, I don’t want packages or anything else from you, but I do want a television. Buy me one and I won’t ask you for anything else.” The attorney refused again.

“Okay. The next time I’m on the yard, I’m going to drive something through someone’s skull.

Sooner or later, someone’s going to ask me why I did it. I’m going to tell them I told you I was going to do it unless you bought me a TV. You laughed and told me to go ahead.”

“That’s not a defense.”’

“Yeah, I know it won’t do me any good, but I suspect the story will be too good not to be repeated all around the legal community and that won’t do you a whole lot of good either.”

Rob got his television.

I had wondered over the years if Rob had been running a bluff or really had mayhem on his mind. I believe the price of a television saved someone some pain. Maybe that someone was me. Sometimes you just have to transmit a message in a way that unmoors the recipient from their personal paradigm to get them to fully understand the information you’re communicating.

I spent a Sunday morning at the law library researching eligibility for dorm living. There were several violations that made you ineligible for the dorms. One was the murder or attempted murder with serious bodily injury of a cellmate. The whole point was I didn’t want to hurt anyone, so I rejected targeting a victim.

The next was sexual misconduct with a staff member. The thought of exposing myself to staff was distasteful, in fact just plain rude, and I might receive a beat down that I’d never recover from. When old people are cracked, they often remain cracked. Pass.

The final violation was escape or attempted escape, either would make me ineligible for dorm living. This had possibilities and thoughts started spinning.

Over the next weeks, I worked my usual six-day week, but on Sundays after church I’d walk the exercise yard while looking over security, mostly thinking about the electrified fence. Almost sixty-years old with shoulder and knee surgeries, I didn’t really want to escape but I wanted it to appear that I was attempting to escape.

I researched electricity in the library and quickly realized that I didn’t know enough about high voltage, amps, conductors, insulators that I could fake a plan to go through the electrified fence. Spaced just outside and higher than the fence were towers with floodlights. The sewing factory had a genie lift we used to change the shop’s overhead lights. If I entered the PIA area after hours and drove the genie lift over to the fence, I could send the platform up high, reach over with a pole we used to clean the top windows in the sewing factory, hook the light, swing over to the outside of the fence, and slide down to the ground. Free at last!

I drew a sketch of the area, noting the light poles and the location of the genie lift. The only thing missing was how to access the PIA area through the non-electrified chain-linked fence.

I spoke to a mechanic in the shop and told him I wanted to buy a universal saw blade to cut open my bunk to hide a cell phone. He told me the blades were inventoried, but he could make me one that would be smaller and cut better than the ones in the tool cabinet. I gifted an eight-dollar jar of Folgers coffee for the blade.

I had to smuggle the blade through security. When I first started working in the shop, you’d walk through the airport-like metal detector and if it beeped you were wanded with a handheld metal detector, and if that beeped as well, the guards would strip search you. In the past year, the prison had upgraded to a new, space-aged metal detector with multiple alarms and complicated controls.

The new metal detector beeped at everything; naked men walked through the detector, and it would beep and flash lights, it would even go off when no one was nearby. When I worked overtime, the guards pushed us through as quickly as possible because it was late, the chow hall was closing, and they wanted to go home, so they simply turned the metal detector off.

I made it through with the blade easily.

I spoke to a friend who had just finished a four-month security housing term for assaulting his cellmate. He clued me that although they’re s’pose to give you a windup radio in the hole, one that you spin a handle to charge up an internal battery pack since they don’t have power outlets or allow replaceable batteries in security housing, in reality most of the radios were broken and the chances of receiving one was slim. He added that you could buy one from a vendor. I ordered one and put it away in my property bin. The radio would fill some of the empty hours in the hole.

With a couple months to go before my annual, the counselor called me into her office.

“Where do you want to transfer in March?

“I want you to apply to headquarters in Sacramento for an administrative determinant. I’m a former Death Row prisoner, and I’m eligible for an override to remain here.”

“That’s not going to happen.”

“I’m not going,” I said flatly.

Sighing, she went and summoned her boss, the Correctional Counselor II.

“What’s your problem?” he gruffly asked. “You’re getting the opportunity to go to level two. Expanded programs, self-help groups, you should jump at the chance.”

“I work all the hours asked of me at the factory. I’ve been employee of the month, I’m on the executive body of the Veterans group, I’m a co-leader of Celebrate Recovery, I go to church, I’ve completed Anger Management, Anxiety and Depression, and since I’m sentenced to Life Without Parole there’s no reason for me to do any of that except personal self-improvement. I deserve an override.”

“Why don’t you just give it a chance? Try the dorms for a year, and if you don’t like it, you can come back here.”

I didn’t believe him.

“I’ll give it a shot. Just document in my file that it’s only for a year, and I’ll let them know at my next annual review if I want to remain in the dorms.”

Silence reigned for a moment or two and then lengthened before he shook his head, and said, “I can’t do that. Sacramento says we have to clear 300 beds for prisoners transferring in from level four. You’re going to have to accept you’re going to the dorms for the rest of your life.”

For two decades I was warehoused inside the death house awaiting execution because burying my body in a grave would make society happy and whole, and now I’m just a body to shove wherever. I don’t have any superpowers, few powers at all, but I felt myself accessing my inner hard-headed nature.

“When I first came to prison, I was on Death Row, and a man with a suit just like yours told me I had come there to die. I’d just have to accept this was the end of the line, my life was over. That was more than thirty years ago, and guess what? He was wrong and I’m still alive. You guys think you know, but you don’t, you don’t know anything about me or what is going to happen to me.”

“Hunter, this is different, you’re going to a dorm setting, that’s the way it’s going to be.”

Another guy I knew on Death Row, Ben, sought therapy after his divorce and formed an intimate relationship with his therapist. Knowing he was on an emotional rebound, he was hesitant, but she said she’d always be there for him. Ultimately, she went back to her husband.

“It’s over,” she told Ben, that’s the way it’s going to be.”

Ben thought about it and decided things might not be the way he wanted, but they weren’t going to be the way she wanted either, so a forty-year-old business executive who had never been in trouble before killed the husband. Ben turned himself in, gave an eight-hour confession, pleaded guilty, and was sentenced to die. I really don’t know if Ben had regrets or not.

“This may not go down the way I want,” I said in a whisper, “but not going the way you want either.”

“You do what you got to do.” The CCII laughed mockingly at me. “When you’re done let us know, and we’ll do what we have to do. We’re offering you a level-two program in eight-man dorms. You don’t get with that program we’re sending you to a two-hundred-man dorm. Do we understand each other?”

When you’re a prisoner, you need to figure out in the first few seconds of any interaction with custody whether they’re going to help you. If they’re not, you must end the communication as quickly, as politely, as possible and move on. I’d already shredded that rule. The CCII wouldn’t or couldn’t help me, I needed to end it. Nodding, I left.

Although I planned to get caught in March, I was starting to stress. The only way to keep a secret is to tell no one, so I was going it all alone, and it’s mentally and emotionally exhausting working on faux-escape plans while sewing so many hours and keeping up my volunteer work.

I had formed some basic priorities; one was not to get shot or hurt anyone else and not to damage any state property that I may have to pay for out of my inmate trust account. Another concern was the possibility that the district attorney of the county might file charges against me for attempted escape. I didn’t care about adding time to my forever sentence, but I didn’t want to pay any fines.

If charged, I thought I’d offer to plead guilty at arraignment, thereby saving the county the cost of my legal counsel and trial, as long as I wasn’t fined more than the three-hundred-dollar court fee. If the district attorney refused and insisted on a heavier fine, I’d represent myself, start filing motions for every possible issue, appealing every denial, attempting to wear down the county with endless litigation.

Going through all the endless scenarios in my head, I started to think it might be easier to just go over the fence and escape. I also had ambivalent feelings. With an attempted escape on my record, I’d never receive a gate pass again. I had a good record, no rules violation report in the past twenty-seven years that I was throwing away. I also wondered if my attempted escape plan might impact other LWOPP’s, barring them from factory work.

Ultimately, I decided that nothing I could do would ever change Corrections’ policies and went ahead with my plans.

My cellmate for the past several years had left for Soledad, and a guy in my church service asked to move in. I was hesitant because I thought when I was arrested; my cellmate would go to the hole under investigation

“I’m awaiting transfer,” he told me, “I should be out of here in a few days.”

“Come on in,” I replied, expecting I’d get myself busted after he got on the bus.

Weeks had gone by, he hadn’t transferred, and I started to worry as time grew short.

My final problem was exactly how to get arrested. I could drop a note on myself but couldn’t be sure the note wouldn’t be traced back to me, and I wanted the escape to appear legit. I decided to use Kurt to communicate with custody.

With my extensive work history as a custody clerk, I was intimately familiar with the disciplinary process. Many prisoners would come to me for help when they received a rules violation report. I was reviewing a rules violation written on Kurt for failure to provide a urine sample for drug testing.

Kurt had been born addicted; his mom hours after his birth left the hospital for a party. She did return a few days later to reclaim him but abandoned him for good at a restaurant when he was five years old. Kurt was walking/talking hate with tracked, scarred arms matching his scarred soul. I didn’t much care about his well-being or what happened to him in a legal or any other sense but enjoyed occasionally striking anonymous blows against the empire.

I refreshed my memory about the drug testing procedures, looked over Kurt’s rules violation report, and noted that the guard conducting the urine test had phoned his housing unit at 4pm and ordered him to report to the gym at 6pm to give a sample. Kurt reported but since he knew his urine would test positive for heroin, he said he was unable to give a sample.

At 7pm, the guard said the three-hour window to provide a sample was over and wrote Kurt a rules violation for refusing to produce a urine sample. What the guard didn’t understand was that prisoners are required to be under direct observation during the three-hour window, therefore the three hours started at 6pm when he reported not 4pm when he was notified, so Kurt had two more hours to produce a sample. If appealed on that basis, the rules violation report would have to be voided.

Like most dope fiends, I figured Kurt was an informant and he’d rat me out. I didn’t want to tell him to rat me out; I doubted he could hold up under the slightest questioning, he’d have to think he really was telling on me.

On a Friday evening with only weeks to go ’til my annual classification, I was standing in front of my housing unit after Celebrate Recovery awaiting the in-line when my new cellmate said to a couple guys, “I knew having sex with that young girl was wrong. I really regret it and have to explain to the Parole Board why it won’t happen again.”

What?! I thought semi-stunned.

Pulling him aside, I said, “Look, your legal issues are between you, the justice system, and God. But now you put it out there, you’re going to be a target, and since we cell together, I’ll be one too.”

“Those guys won’t say anything. They’re sex offenders too.”

“I did not want to know that.” I put out my hands, fending him off.

“Yeah, we’re in a group. The prison keeps it quiet. We meet once a week for cognitive therapy.”

The housing unit door opened, and I kept wondering how young is a young girl? Seventeen? Seven? Seven months? What the hell! I felt absolutely overwhelmed, spent, I’d had enough.

At breakfast Monday morning, I told Kurt to meet me in the library when yard opened up, and then I went to the work gate, told them I didn’t feel well, and I wouldn’t be sewing that day. Returning to my cell, I placed the universal saw blade and the escape diagram in a folder and wrote, “Mike’s Sports League” on the cover. Kurt was a big-time fantasy football fan, and I thought the title would draw him in.

Meeting Kurt in the library, I went over his rules violation report, and then went to pick up the appeal form he needed to file leaving the folder right next to him. Peeking, I watched him looking over my notes. Noticing the folder marked sports, he opened it up to the escape diagram and cutting blade, stared for a moment, and then quickly shut the folder. I returned to the table, helped him fill out the forms, and he said he had somewhere he needed to be and took off.

Seconds later, I followed and watched him being searched and escorted into the sergeant’s office. I wondered where to hang out while waiting to get arrested. Just then my housing unit had an in-line, so I went back to my cell. I placed the folder on the desk and sat on my bunk. My cellmate was at work, so I was all alone. Idly, it occurred to me that I could flush the diagram and the blade down the toilet, all the proof would be gone, and I could just go to work on the next out-line. Did I really want to go to the hole?

My cell door opened, a guard told me to freeze, handcuffed me, and reached onto my desk and opened the folder. After glancing inside, he started to escort me to the sergeant’s office. As we cleared the housing unit, I thought, I guess it’s too late to say it’s just a ploy, let’s forget about the whole thing. I chuckled nervously, he thought I was trembling, and asked me, “What’s wrong?” I just shook my head

Strip searched, I wasn’t questioned, but simply marched to security housing and placed in a cell. Lying on the bunk, I thought, here we go, and dozed as adrenaline ebbed away making me feel numb.

On Tuesday, I was escorted to an office where the security squad sergeant had stacks of documents in front of him including my United States Naval record. I wondered how he got that so fast.

Forty years ago, I had been a Naval Aircrewman. I wasn’t a pilot; I sat in the backseat of an aircraft carrier-based jet and operated various avionic systems. Part of my training was SERE school, Survival Evasion Resistance Escape, and the sergeant was intently reviewing the record.

A former Marine, apparently the sergeant wanted me to feel comfortable, so I might open up to him. We swapped sea stories for some minutes. Do you know the difference between a sea story and a fairytale? One starts, “Once upon a time…” The other begins, “This is no bull…” Otherwise they’re exactly the same.

The sergeant told me my cellmate and Kurt were in the hole, suspected of involvement. I explained that neither of them had a clue, and he said he’d kick them loose if I’d answer a few questions.

“We’ve got cameras all over the yard, how were you going to cut the fence in front of them?

“I was going to pick a night when it’s raining, so water would obscure the lens. A month ago, I went out in the rain and sat in front of the fence for an hour. No one said anything.”

Shaking his head, the sergeant asked about the thirty-foot genie lift. I explained it was left each night outside the shop in a charging station. I’d drive it over to the fence, go high, hook the light with the plastic pole used to clean shop windows and let gravity take me to freedom.

“A former condemned prisoner going over a prison fence is a nightmare scenario,” he said bluntly. “Our only real job is to keep people like you locked up. This would make national news and people would lose their jobs. I’m placing a chrono in your file recommending you never be housed in less than level three security.”

On Thursday, I was placed in a holding cage awaiting classification committee. I didn’t see Kurt, but my cellmate was locked next to me. He said the sergeant told him I’d cleared him, and he was going to be released from the hole that day. He added that he forgave me. Good to know.

The committee had a gaggle of uniforms and suits, all kissing up to the Warden.

“You did this on purpose!” raged the CCII, mocking laughter absolutely absent. “This is all just a fraud to stay out of the dorms!”

Thinking it over while the CCII glared at me furiously, I wondered why he cared so much about where I was housed for the rest of my life. Why did he care where I spent my golden years?

“If I tell you it’s a fraud, are you going to void the rules violation report and kick me out of the hole and to work today?”

“Hell no!”

“Then why are we talking about it?”

“What did he say?” I heard the Warden whisper to the suit on his right. After receiving an answer that I couldn’t hear, he added, “Are all my lifers going to do this?”

A suit stated, “You’re being charged with possession of dangerous contraband. It’s a District Attorney referral. You can have your hearing now or postpone pending the D.A.’s decision to prosecute.”

Surprised by the charge, I asked, “Dangerous contraband?”

“That’s correct.”

I could be written up for dangerous contraband: the saw blade, or out of bounds: attempted escape, but not both. The captain had to pick one or the other. It’s considered stacking or overcharging to prefer both charges. Oddly enough, dangerous contraband did not carry a security housing unit term, but out of bounds carried a year. If I pleaded guilty, I’d return to classification the following week and they’d have to kick me out of the hole.

“Can I waive my twenty-four-hour notice and have my disciplinary hearing today?”

“You sure you want to do that? Anything you say at the hearing can be used to prosecute you. Not only that, if you’re not within 120 days of your release date from security housing with a finding of guilty at the hearing, you’ll be transferred to the Corcoran Long Term Security Housing Unit.”

Everyone had heard horror stories about the LTRH at Corcoran. No one wanted to be housed there. “I’m sure.”

I signed the 24-hour waiver and was returned to my cell where I high-fived myself. I’d go to my hearing, plead guilty, see committee the following week and be released from the hole. The rules violation report along with the security squad sergeant’s chrono would keep me out of the dorms. Mission accomplished.

After dinner, I was handcuffed and taken to the lieutenant’s office.

“Are you ready for your hearing?”

“Yes.”

“Bet you are. You were too eager, Hunter. We looked through the regulations, figured out your scheme, and your rules violation report is being voided. We’re writing a new one for out of bounds – escape tools/plans. Still want an expedited hearing?”

“No. I’ll wait ’til after the referral to the District Attorney comes back.”

“Okay, but we want you out of here. You’re transferring.”

“Where??? “

“You’ll find out when you get there.”

Since I’d been to committee, I was eligible to receive a few items of my belonging that are allowed in security housing such as toothpaste, writing material, books. “I want my radio.”

“We don’t have a radio to give you,” the property guard started to close my tray slot.

“I don’t want your radio. I want my radio.”

“You can’t have batteries in the hole, and there are no electrical outlets. You have to have a windup radio.”

“I have one in my property.”

Digging through my two bins, he found the radio. “This’s one of ours,” he protested.

“No, it’s got my name and number on it. I have a receipt from the vendor.”

Finding the receipt tucked away in my address book, the guard exclaimed, “Someone knew they were going to the hole.”

“Been here before, suspected I’d be here again.”

It was way cool being able to listen to sports radio, news, and music, the sounds of the world beyond gray walls and high fences. The guards set up a big screen TV to watch the Super Bowl. Peering through my cell window, I saw the Eagles beat the Patriots.

One morning I was pulled from my cell and taken to R&R for transfer. No one would tell me where I was going. Planted on the bus, I discovered from other prisoners that they had come from Mule Creek Prison, and the bus was going to North Kern. This did little to enlighten me, since the Mule Creek prisoners were just doing an overnight before moving on to level two Avenal prison the next day.

I stared out the window, as the scenery changed from the green, cool foothills to dusty, brown central valley California where there are no four seasons, just windy winter and hazy summer. We stopped for a meal. I awkwardly ate my bag lunch with hands locked to a waist-chain, and stared out the window at people strolling by. Watching their freedom, wandering wherever they were inclined, I realized how lost I would’ve been if I’d gone over the fence. A stranger in a strange land,

Finally, the bus rolled into North Kern. My legs stiff after hours in chains, I clanked down the bus stairs and into R&R. A friendly guard asked, “Mr. Hunter, you staying with us or moving on?”

“No idea, they wouldn’t tell me.”

In a holding cell for a few hours, I was given a lockup order placing me in the hole pending transfer to Pleasant Valley the next day. I was housed at Pleasant Valley from 2004 to 2015, I was returning not exactly wreathed in honor and glory. Oh well.

Back on the bus at 4am, we pulled into Pleasant Valley around 9am. As soon as I stumbled into R&R with chains a clanging, I heard a guard call into the sergeant’s office, “That’s the Captain’s clerk.”

Pulled out of line, I was escorted to see the sergeant. I didn’t know him, but he knew me.

“I’m e-mailing Lieutenant Beck. He wanted to know when you showed up.”

I had worked for Beck for years and years when he was a sergeant and then a lieutenant; I wondered how our reunion would go.

“Tell him the cannibal is here.”

“What?”

“The LT loves to tell people I was on Death row because I eat people.”

“Really?!”

“Yeah. Let him know the cannibal is here.”

Inside a cell in the hole, I sighed, made the bunk, kicked back and closed my eyes.

The next morning, I was escorted to a conference room. It was Lieutenant Beck.

“Couldn’t believe when I saw you on the movement sheet for security housing ’til I saw the rules violation. Didn’t want to go to the dorms???”

I first met Beck when he was a sergeant, and I was the third watch sergeant’s clerk. I was copying rules violation reports when he asked me how I was doing. “Fine, Sir”, I answered.

Other clerks criticized me for saying sir, but they didn’t understand that I used formality as a shield, gaffing custody away. After a few more attempts to engage me and I remained distant, Sergeant Beck gave up and left me alone.

A few nights later, a fight broke out on the yard. Alarms, the combatants were handcuffed face down on the ground, ready for escort when out of nowhere a guard ran up and crashed his knee onto one of the prisoner’s head, knocking him out. Dread, a gangbanger and member of a security threat group, popped to his feet and started cursing while advancing on the guard, but he was quickly taken down, cuffed, and escorted away. An ambulance carted off the unconscious prisoner.

The weekend sergeant, Mac, ordered me to generate paperwork confining Dread to his cell and write him a rules violation report for inciting violence. The report did not mention the guard’s use of force on a handcuffed prisoner.

At Dread’s disciplinary hearing, he brought statements from prisoners describing the entire event. The lieutenant found him guilty and gave me the disciplinary package to process. Minutes later, Sergeant Beck took the package from me and went to speak with the lieutenant. Our offices are next to each other, and I won’t say I was ear hustling, but I heard Beck telling the lieutenant, “I’ve reviewed the yard surveillance footage and the statements the inmate brought to his hearing are accurate. If you don’t call outside investigators, I’m calling them.”

Sergeant Beck and the LT went and escorted the guard who had kneed and knocked out the prisoner from the facility pending the outcome of the use of force investigation. I never saw him again. Dread’s rule violation was voided, and he was quickly transferred to another prison.

Impressed by his actions, I started studying Beck and noticed everyone, whether they wore guard green or inmate blue, liked and respected him. Curious how he had become so popular, I finally realized that Beck’s strength is not that he tries to be liked, but rather that he likes people, so naturally they like him in return. First as a sergeant and then as a lieutenant, I clerked for Beck, and he always told me, “All I ask is that you don’t steal from me or lie to me.” I never did and he always looked out for me.

Now, as he was asking me about my rules violation for escape tools/plans, lying was not an option. I could tell him I didn’t want to speak on the matter, and he’d honor my wishes, but I found myself running everything down to him.

“They locked up the rat too?”

“I didn’t see him, but the security squad sergeant told me was locked in the hole under investigation. Expect he’s out by now.”

“That’s what he gets for trying to barter you to get out from under his own misdeeds. Okay, we need to turn this around,” Lieutenant Beck said. “The county has declined to prosecute, so only the rules violation is left. Just plead not guilty at your disciplinary hearing; and you’ll be kicked out of the hole next week.”

“I didn’t go through all this,” I protested, “just to be found not-guilty and go to the dorms.”

“The security squad sergeant at Sierra wrote a chrono, they won’t send you there anymore.”

“If there’s an audit of my file, there won’t be any underlying documents supporting the sergeant’s chrono. Sacramento could void it and make me eligible for the dorms.”

“You didn’t escape, didn’t hurt anyone, and didn’t damage any property. The only reason this has gone so far is Sierra is embarrassed. They should’ve applied for your administrative determinant and kept you there. They were lazy. Just go to your hearing, we’ll find you not guilty, and apply for an administrative determinant from here. If your administrative determinant is denied, we’ll just change the font on the application, resubmit, and that will make all the difference.””

We burst out laughing.

On a Sunday when I was captain’s clerk on Facility-A, Sergeant Story called me into his office and ordered me to write a Captain’s Agreement sending an inmate to Facility-D due to safety concerns.

“Does the Captain know about this?”

“In the absence of a lieutenant or captain, it’s my call. Just write the agreement.”

I figured the safety concerns revolved around a drug debt, and I knew the Captain would want to know every detail of the debt before he let the inmate leave the facility. I’m a custody clerk, a criminal, not custody, so I did the paperwork and left a copy on the Captain’s desk.

On Monday, the Captain called me to his office and told me never to do that again without first having someone call him on his cell phone.

The following Sunday, I was watching my beloved San Francisco 49ers play when my cell door opened and I was ordered to Sergeant Story’s office. The Captain had ordered him to write a chrono explaining why he let the inmate transfer to another facility for safety concerns without confessing to purchasing drugs and naming his supplier.

Sergeant Story asked me to assist him write the chrono. Many drafts later, the sergeant was still dissatisfied with the chrono. The problem wasn’t the writing; the problem was no reasonable explanation existed in any universe. Looking over my latest effort, Sergeant Story said, “Maybe this chrono would work if we change the font.” My head blew up, and I left to watch the second half of the football game.

“The District Attorney has declined to prosecute, so I’m on the clock for my disciplinary hearing,” I talked through the process ahead of me. “I have to be heard for my rules violation in the next ten days or so. There’s no way Sacramento is going to act on my request for an administrative determinant that quickly. With good time, I’ll be out of here in just over four more months. I’ll do the time.”

A couple weeks later I pleaded guilty. Since I was less than 120 days away from my release date from security housing, I didn’t transfer and just remained there to finish my disciplinary term.

I enjoyed the camaraderie of security housing. We were all miserable; all had virtually nothing but found ways to make it a community. I’d go to the outdoor cages lined up in a row one after another and do my old guy workouts. The cages were filled with men charged with violent, prison offenses: fights, assaults, battery with a weapon, attempted murder; I was the only escape tools/plans, the outlier.

We’d save our peanut butter, jelly, graham crackers, and send them to a cell where once a week a prisoner made cookie wheels. We feasted and sugar rushed, a high point in an otherwise bleak existence.

With two weeks to go in late June, I was reading in my cell, thinking that security housing was filling up due to summer violence, and custody might kick me out early to make room for other misbehaving inmates. Out of nowhere, the counselor popped up in front of my cell window.

Pushing a cart full of my belongings out of the hole to Pleasant Valley’s Facility-A, I wondered if there would be retaliation for the faux-escape attempt. There was none. I worked briefly cleaning showers and then was assigned as the Orientation Housing Unit clerk. Later, a lieutenant I worked for previously made me her clerk before I moved onto the library,

Every year, I go to classification and the suits continue me here on present program, and I wonder, why couldn’t they have just done that at Sierra?

I know prisoners who dream of women, parties, and wild times. I dream about simply sipping coffee on a wooden bench on the grass outside of a sewing factory while watching hawks surfing a flawless, azure sky.

The End

1 Comment

WrongToy

February 12, 2022 at 10:24 amJamestown is a camp. Why wasn’t it just level 2 to begin with or made that way once LWOPs could qualify for L2?